The Invisible Social Crisis

Work Leaving Families Behind

Source:CW

More than 1 million Taiwanese families live apart because of professional obligations. How are couples coping with this new social phenomenon and dealing with the challenges it entails?

Views

Work Leaving Families Behind

By Sherry LeeFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 587 )

When Teng Huei-sheng got married 15 years ago, she never suspected that she and her husband would live half of their time together apart, separated by a long distance. A manager for a publishing company, the always-smiling and warm Teng has two adorable daughters and at 38 years old is in her prime. But she epitomizes what has become known in Taiwan as the “left-behind wife.”

Teng’s husband, Wang Shun-cheng, has spent the past seven years in China building a business while Teng has shouldered the responsibility of caring for her own family and that of her husband’s on her own. When her husband’s business was floundering in its first three years and running up debts, she had to work overtime to preserve the family’s finances. As though fleeing from an expanding black hole and fearing that her marriage would be swallowed up with hardly a trace, she once thought about getting a divorce.

Teng, who mocked herself as the “away spouse” in this long-distance marriage, revealed many of the concerns of a “left-behind wife.”

“I don’t know what the future will bring. How many years can this life continue?” she says, revealing her innermost concerns.

In the past few years, Taiwan has spawned a sizable but relatively hidden group of “left-behind spouses” and “left-behind children.” Their definition of family differs from the norm, their family members separated by substantial geographical distances.

Relocating regionally has become the new normal for Taiwanese workers. For those who move overseas to work, they and their families endure a constantly revolving cycle of difficult waits and brief reunions.

More, Younger Workers on the Move

Though Taiwanese have been flowing west to China to set up businesses and work since 1988, mostly in the high-tech and old-economy manufacturing sectors, the migration in recent years has expanded to the service sector.

Lin Chu-chia, deputy chief of the Mainland Affairs Council, Taiwan’s main agency for coordinating China policy, has been observing the willingness of senior Taiwanese executives to work in China since teaching in National Chengchi University’s EMBA program in 1990. “In 1995, there were still only 20 percent willing to go, but by 2005, 80 percent were willing to work on the mainland,” he says.

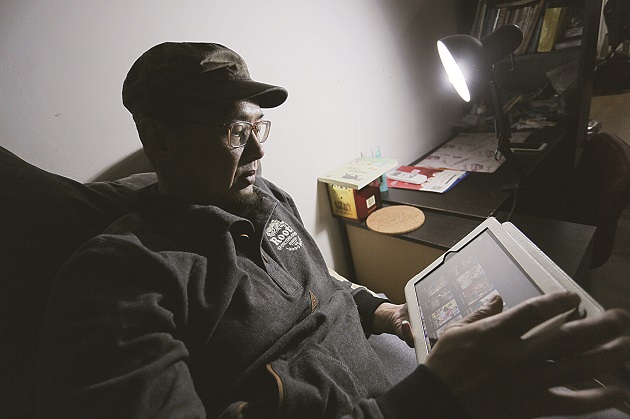

When he's alone, Taiwanese businessman Wang Shun-cheng watches Korean and Japanese TV dramas, helping him save money and kill time.

When he's alone, Taiwanese businessman Wang Shun-cheng watches Korean and Japanese TV dramas, helping him save money and kill time.

Taiwan’s Straits Exchange Foundation, a quasi-official body responsible for contacts and negotiations with China, estimates there are currently 900,000 Taiwanese working and living in China based on information from Taiwanese business groups there.

But estimates by private organizations and academia put the number much higher, at about 1.5 million.

That means that around 10 percent of Taiwan’s national workforce of nearly 12 million people works in China or travels frequently between the two countries, according to conservative estimates by both the government and the private sector.

“Taiwan’s industrial development continues to face serious constraints, while in the future, demand for manpower will emerge in China’s high-end, high-wage service sector,” says the MAC’s Lin, laying out Taiwan’s predicament in retaining talent.

“In the banking sector, for example, Bank of Taiwan at most has 300 branches in Taiwan and a need for 300 branch managers. Taiwan’s market is only that big. If you go to China, you can create another 300 branches and branch managers and more high-paying jobs.”

With the ASEAN Economic Community coming into existence in 2015, the number of white-collar workers relocating to Southeast Asia has also been on the rise.

Vietnam, Malaysia and Thailand are the three ASEAN countries with the highest number of Taiwanese businesses and businesspeople. Based on estimates from local Taiwanese business associations, there are around 12,000 Taiwanese-invested enterprises and more than 200,000 Taiwanese in the three countries alone.

Not only have there been more Taiwanese workers moving overseas, they have been doing so at an increasingly younger age.

Andy Yang, managing director of executive recruitment firm Ozific International Consulting Co., has more than a decade of experience in this executive headhunting market. He says that since 2010, the average age of professionals heading to China has fallen to a range of 38 to 48, down from 48 to 55 previously.

Though more young, single Taiwanese are pursuing careers abroad than in the past, this 38 to 48 group that form the backbone of society are mostly tied down by commitments, either raising children or taking care of their parents.

Thus, as working abroad has become the new normal, the separation of families has inevitably followed. The question is, what are the risks and opportunities presented by this emerging phenomenon, and is Taiwanese society ready for it?

An Underestimated Intimacy Crisis

Shen Hsiu-hua, an associate professor in National Tsing-Hua University’s Institute of Sociology, has focused her research in recent years on how the intimacy between Taiwanese couples changes when one of them works abroad. Her main conclusion? Divided families have spawned a class of “situational singles.”

These “situational singles,” Shen explains, are married people who after living far apart no longer necessarily observe the sexual and emotional fidelity normally found in a marriage.

Shen also discovered through her research that the farther the distance between married couples, the easier it is for “intimacy jet lags” to occur. But the problem even exists for couples separated only by the Taiwan Strait who still live in the same time zone. Their senses of space and time and the social interactions and pace of life can be completely different, “so when the separated spouse returns home, the couple doesn’t know how to get along anymore,” Shen says.

Many studies in the sociology of love address the concept of distance, and even some conclude that distance helps maintain relationships. But most studies have found that long-distance relationships are difficult to sustain.

In a “China Impact Survey” conducted in 2012 and 2013 by Lin Thung-hong, an associate research fellow in Academia Sinica’s Institute of Sociology, he found that the divorce rate among couples where one spouse went to China on business three times or more in a single year was double that for couples who rarely traveled there.

Long-distance marriages ending in divorce has become a trend, though as the MAC’s Lin stresses, the higher divorce rate would be evident whether a spouse was working in a Western country or in China. But what cannot be denied, as Lin argues, is that “Taiwan’s divorce rate is now the third highest in the world, and the cross-border population is partly responsible for that.”

Lin urged the government to assess the social risks when contemplating economic and trade ties between Taiwan and China.

“We are paying an unseen price in terms of our health and our families. As society becomes more open, have families and society prepared supporting measures that deal with such issues as cross-border marriages and reconstituted families after failed marriages?” he says.

The separation of couples because of the need to work overseas has not only taken its toll on married relationships and the ability of adult children to take care of their aging parents. The nurturing of the next generation has also emerged as a huge concern.

Who Raises the Kids?

The mother of 14-year-old Ling Chih-chieh (a pseudonym) runs a business in China, and her father is constantly busy at work. From a young age, Ling has lived at boarding schools in Taichung and Taipei.

“In my first year of elementary school, I could blow-dry my hair; my day care center gave me warmth. I didn’t go out of my way to get close to my parents and in any case they don’t understand me,” she says.

Teng Huei-sheng and her two daughters always head to the airport to welcome Teng's husband, Wang Shun-cheng, when he returns home from China, where he runs a business. When they reunite, their faces are a mix of longing, sadness and satisfaction.

Teng Huei-sheng and her two daughters always head to the airport to welcome Teng's husband, Wang Shun-cheng, when he returns home from China, where he runs a business. When they reunite, their faces are a mix of longing, sadness and satisfaction.

The increase in numbers of these “left-behind children” results in part from choices parents have to make simply to survive. That has created a massive demand for boarding schools that can help parents take care of their children.

In Taichung, for example, which has the most boarding schools of any city or county in Taiwan, enrollment in several well-known private boarding schools has not declined despite the steady fall in the country’s overall student population brought about by a low birth rate. Enrollment at a boarding school in Taipei, Huaxing High School, has even risen dramatically.

The Taipei school’s director of academic affairs, Lu Teh-jun, says that with the rising number of families that move frequently or single-parent households, schools are now responsible for taking care of children’s basic needs – feeding, clothing, housing and educating them – but teachers will never be able to replace the role of parents.

Faced with moving across regions and changing work locations, when a family is about to be split apart, what can the spouse who has been assigned abroad do while working hard at the new posting to keep the family together?

J.X. Chou, the 35-year-old son of the founder of the Toseva Group, Taiwan’s biggest woodworking processor and manufacturer, left Taiwan when he was young to study in Singapore. After graduating from university, he was called to Myanmar by his father to join the family business there.

While pursuing his career in Myanmar, he made a real effort to care for the family he left behind in Singapore. For five straight years, he has commuted regularly between Yangon and Singapore, flying between the two cities once a week.

Every Friday at 3 p.m., Chou leaves his office for Yangon International Airport. By the time he gets home in Singapore, it’s 11 p.m., and his young daughter is usually already asleep. “If I didn’t go home on weekends, she would not know her father,” Chou says.

On the flight to Singapore from Yangon, Chou is joined by several Singaporeans in similar situations, flying home every Friday and then flying back to Yangon the following Monday at 8 a.m.

“The trend has been particularly evident over the past three years. Myanmar has opened up, and more people are coming here to do business. There are also many Taiwanese,” he says.

Chou has solved the predicament of a “left-behind family” by regularly flying home. But a round-trip economy class ticket between Yangon and Singapore costs the equivalent of about NT$13,000, which has added up to more than NT$3 million in commuting costs over the past five years. Most people do not have the same benefits Chou does when posted abroad.

Chin Li-ming, senior vice president of manpower agency 104 Job Bank, has worked in the human resources field for 20 years. “Being divided across borders has become a trend, and it’s a difficult problem to solve,” he says, and one that is getting even more complicated to deal with.

Based on data from several big databases, Chin observes that the benefits given to Taiwanese workers sent to China have dwindled to practically nothing, with housing and moving allowances and subsidies for the education of an employee’s children often no longer provided.

Base salaries for overseas posts, which used to be two to three times what people earned in Taiwan, are now only about 20 to 30 percent more than the pay at home, and where employees used to get plane tickets to return home once every one or two months, that has changed to four times a year. In some extreme cases, Taiwanese workers are treated the same as local hires.

“As more talent has flowed abroad, the model has gradually evolved toward employees absorbing family-related costs,” Chin says, described the shrinking of compensation and benefits for Taiwanese workers.

National Tsing-Hua University’s Shen believes that Taiwan’s small and medium-sized enterprises have in fact used the family as a pillar of support. “To obtain economic security, families have been able to internalize all costs, making sacrifices for the company and the economy,” she says.

Different views exist on whether families being separated by work represents a side effect of globalization or a form of positive energy. But caught in this irreversible whirlpool, talented people always hope to bring an indomitable will abroad in pursuit of a career and rack up substantial achievements and memories before returning home.

Teng Huei-sheng, who has been “left behind” for seven years, is still waiting for the day when she is reunited with her husband. Her attitude toward her husband’s regular absence has evolved from initial complaining to acceptance to a wry smile. She has learned to drive a car, studied the art of tea, developed the strength to attend to both work and family, and even slowly experienced more of the world through her husband.

As his business has gained steam, her husband Wang Shun-cheng has returned home more frequently, but she still constantly reminds him that “when you’re young, going somewhere else to live and work is great, but I only hope you don’t forget to come home in the end.”

In a globalized workplace, Taiwan needs talented people to go abroad and battle, but as that happens, society and companies need to weave a strong safety net for these “left-behind families” as a pillar of support while they wait to be reunited.

Translated from the Chinese by Luke Sabatier

【Additional Reading】