How I Tried (and Failed) to Become an Internet Celebrity in Taiwan and China (1/2)

Source:Stephen Turban

Stephen Turban is a recent graduate of Harvard College and an alumnus of Jianguo Municipal High school. Here he shares his personal attempt in becoming an internet celebrity in China and Taiwan and his observation on the two’s social media landscapes. (Part 1)

Views

How I Tried (and Failed) to Become an Internet Celebrity in Taiwan and China (1/2)

By Stephen Turban/Seeing the World as a ForeignerCrossing@CommonWealth

"You see, Stephen, you have to play to your strengths on Chinese social media." Her eyes ran over me, evaluating my vaguely Jewish, almost pre-pubescent frame. "Perhaps you should post fewer photos." She then reached for my phone and opened my fledgling Weibo account.

From the outside, Lara Sun (孙雨彤), looks like a normal 20-something Chinese girl. If you meet her, you'd think that she's smart, funny, and has a crushingly accurate view of your (dismal) modeling career. She's someone you'd like to be friends with. But what you wouldn't realize is that thousands of people feel exactly the same way.

Social Media in China ── It is a Big Deal

Lara and her twin sister Sara are veritable internet celebrities ─"网红"─ in China. Combined, they have nearly a million followers on Weibo, China's Twitter. We met as co-hosts for Harvard's Chinese New Year's Gala where I was the token foreigner who spoke Mandarin. Interested in the prospects of fame, glory and someone besides my mom commenting on my online posts, I reached out to Lara. I wanted to know: could I join the Chinese social media sensation? Could I become an internet celebrity in China?

If you don't know, social media in China is a big deal. Really big. By some estimates, there are 600 million social media users in the country. Huge names elsewhere, Facebook, Google, and Twitter are blocked in the country. As a result, Chinese-specific platforms have developed. Of those, the most ubiquitous is the messaging and social media app, Wechat. Another is Weibo, a microblogging site similar to Twitter with more than 300 million users.

Social media also plays a larger role in the lives of Chinese citizens than in the lives of those in the U.S. A survey by McKinsey & Company recently found that more than 91% of Chinese internet users used social media in the past 6 months; that’s compared to 61% in the U.S. Because of a distrust in centralized communication, social media also has a larger influence on purchases in China than anywhere else in the world.

Social media celebrities not only have fame in China, they also wield remarkable power over others' behavior.

Before meeting Lara, I had the briefest taste of Chinese celebrity. In high school, I lived in Taipei as an exchange student and learned Chinese, after which, I went to Harvard for my undergraduate education. During my senior year in college, a Taiwanese friend interviewed me and wrote an article about my time in Taiwan. She sent me the article the morning of Thanksgiving, and by the time I checked it that afternoon, it had been reposted hundreds of times.

But, when I spoke with Lara and her sister I knew that my article was small speck in the galaxy of social media. For a bit of context, her sister (Sara) once posted a picture of bubble milk tea next to a picture of her partially grimacing. The result? 13,000 likes.

When I post a picture of this on Facebook, I only get a comment from my aunt saying that I should avoid sugary drinks.

When I post a picture of this on Facebook, I only get a comment from my aunt saying that I should avoid sugary drinks.

Why I Wanted to Be a Chinese Celebrity

I had a few motivations for joining the stratosphere of Chinese social media stardom. For one, I thought it would just be a weird adventure. What happens in the dark armpit of Chinese social media? I wanted to find out. I also wanted to be that armpit.

Secondly, I thought it would be fun to explore the life of internet fame. What is it like to have people know about you without you knowing anything about them? I knew that would never happen in the U.S. But, perhaps there was niche for a foreign Chinese speaker.

Finally, I was in my senior spring of college. The most important thing I needed to do this semester was to guarantee that my liver would survive for at least another decade. I was bored. I needed a project and this seemed like the perfect opportunity.

I returned from my daydream to see Lara sitting in front of me with my phone in her hand. She had already begun downloading the Twitter-like app Weibo. She saw me looking, and turned to show me the screen, "So, what do you want your handle to be?" she asked.

I hesitate. "Stephen?"I replied.

Her forehead crinkles, as if finally realizing that my only marketable talents are that my skin is the color of soured milk and that I go to Harvard.

"Let's call you, ‘哈佛一哥 Stephen,’"she replied after much thinking. Roughly translated, this is: "Some guy who went to Harvard. His name is Stephen."

It nailed my personality perfectly. With a new title and a fully developed Weibo account, I was ready for stardom. I just needed to create my first post. Luckily, Lara stepped in again.

You see Lara has two natural advantages: First, she is witty. Second, she is roughly 3-7 points more attractive than I am on a scale out of 10. She helped me construct a first post, a quick joke and combined it with picture of the two of us. Then, after she posted it on my account, she went back to her Weibo account and simply liked the post.

And so the flood gates opened.

Within minutes, my follower count went from 10 to 100 to 300. By the end of the week, I had nearly 700 followers. What I learned almost immediately was the power of influencers in China. Though social media is a distributed system, influence still seems to collect among a small percentage of the population. When a few of those people notice you, the implications are potentially enormous.

For the next few weeks, I rode off of that high, submitting normal posts with a few pictures and attempting-to-be-funny taglines. However, it wasn't until I worked with another social media starling that I learned about a more interesting phenomena in Chinese social media: the rise of "live broadcasters."

Understanding Live Broadcasts in China and Taiwan

In China and Taiwan, one of the biggest social media phenomena has been the rise of 直播(zhibo) or "live" showings. These are essentially live broadcasts in which one or two people sit in front of a phone’s camera and talk, dance, sing, or otherwise look attractive to a real-time audience. Audience members can make comments, like the posts, or send money in the form of virtual gifts to these 主播(zhubo)or anchors.

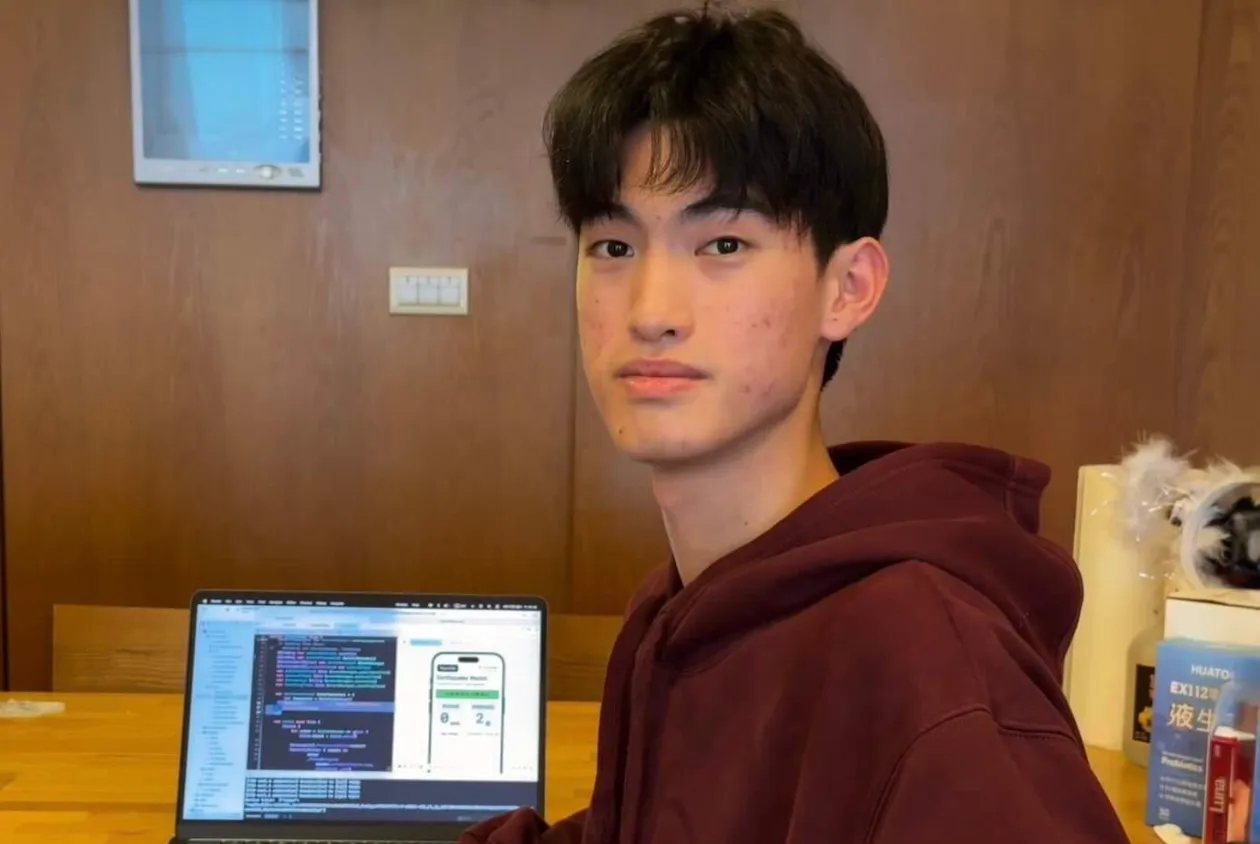

Roughly what I look like when I live broadcast

Roughly what I look like when I live broadcast

Live broadcasts exist in the U.S. But, they are not nearly as popular as they are in China and Taiwan. In the mainland, over half of all social media users, more than 344 million, have used one of China's live streaming apps. Particularly famous anchors can make hundreds of thousands of dollars each month, mostly from gifts given from fans.

A few weeks after Lara introduced me to Weibo, a friend from Taiwan reached out about a new opportunity. Would I be interested in co-hosting a live broadcast talk show for a large Taiwanese media platform?

The friend's name was Alice Yang and she was a social media heavyweight in her own right. Though she has since shut down her social media presence, at the time she ran a fan page on Facebook with over 10,000 likes and thousands of active readers. She wrote for a Taiwanese magazine "The Crossing" which has nearly 250,000 Facebook followers.

At this point, it would be important to note that social media in China and Taiwan are two very separate entities. Though both groups use Mandarin as their primary language, the way they use social media is very different.

For a U.S. audience, Taiwan is the easier to understand. Facebook is a dominant presence in the island with more than 80% of all internet users registered on Facebook. The next most popular app is Line, which is a Japanese messaging service. Following that is Instagram, Twitter, and then WeChat. When I tried to gain exposure in Taiwan, I primarily used Facebook to reach new fans.

Mainland China, on the other hand, is a completely different monster. Because the government has blocked popular platforms like Facebook and Twitter, China-specific platforms like WeChat and Weibo have developed. Because Weibo is more like Twitter, in that it is a one-to-many platform, it was the primary focus of my Chinese social media adventure. So, at the beginning, I chose to split my efforts into two. I'd spend a portion of my time on Facebook with a Taiwanese audience and another portion on Weibo for a mainland Chinese audience.

My First Live Broadcast⋯⋯180,000 Views Later

Alice and I met at 7:00 AM that morning and almost immediately I knew she meant business. For one, Alice had a tripod for her cellphone, which I didn't realize was possible. Second, Alice had a glint in her eye that simultaneously showed excitement and that she would kill me if I messed this up.

At 7:30 AM, we entered The Crossing's Facebook page, wrote a quick description of our talk, and hit a big "Live button."

And then we waited.

And waited.

On the top left corner Facebook displays a counter of the number of people watching your live broadcast. For the first few seconds that number stayed at an unintimidating zero. Then, the number slowly began to grow. First there were 50 people watching. Then 100. Soon, there were nearly a thousand people watching Alice and me live from around the world. Most of these people were likely sitting on the toilet, but still it was exciting.

At first, the show felt a bit strange. In theory, we were talking to a thousand people. Yet, it still felt like we were sitting in a dining hall chatting alone. However, as the conversation went on, I could understand the appeal for both fans and broadcasters.

What's remarkable about live broadcasts is their interactivity between fans and announcers. As more people joined the live broadcast, they'd send questions and make comments about what we'd said. By the end, Alice and I had probably spent more than half of our time directly answering those questions and comments, as opposed to following a set script.

After about an hour, Alice and I waved goodbye to the audience, wished them a happy Chinese New Year and signed off. We'd chatted about our lives, listened to the concerns of Taiwanese students, and talked about some of our favorite study habits. I didn't expect this – but I loved it. I actually felt like I connected with some of the viewers, something I don't think I'd have felt through another medium.

Over the following few months, I did dozens of live broadcasts with Alice and another friend Emily Song. In large part, this was because I really enjoyed chatting with fans directly. But there was also another side benefit – I got to improve my Chinese. Over time, fans would get to know me and would correct my Chinese or teach me new phrases that I didn't know before. Some of those phrases included "Stephen, your haircut looks like your head ate a gerbil," but still, it was fun.

Being "Blocked" By the Platform

Unfortunately, live broadcasts have become a touchy subject in mainland China. In February, the central party began a crackdown on live accounts, particularly of individuals overseas. The crackdown resulted in Sina Weibo changing their live broadcasting policies to make it impossible for foreigners to broadcast. After my account had been blocked for a few weeks, I knew I needed to try a different outlet. So, I moved to the second-hottest form of media in China: video.

Translation: You currently are not allowed to create Live content

Translation: You currently are not allowed to create Live content

I didn't quite understand what happened. Perhaps, I wasn't connected to Wi-Fi? Did I not have enough data on my plan? Perhaps my phone's update had disabled live videos? Luckily, Emily was there so, we simply used her phone and Weibo account to film the live broadcast.

But, over the following few weeks, my account continued to have problems. And so, I began to get suspicious. I reached out to a few Chinese friends and, strangely, none of them seemed to have problems with their Weibo account. Could it be something about my account that was particular? What might have happened?

I began to ask people directly. Why was my account blocked? Soon, the answer became clear.

It was because I was a foreigner. Sina, the company that owned Weibo, was attempting to get rid of all foreigners from the live-streaming part of the platform.

As I alluded to earlier, in February, 2017 the Chinese government passed new regulations that banned foreigners from using live streaming platforms. My account had passed unnoticed for the first few months. But, once it reached a critical following, it was noticed by Sina and shut down. I could still send photos, videos, and texts. But, my ability to connect directly fans via live videos was gone.

I was furious. I felt excluded for doing nothing except for being foreign. Why did it matter that I wasn’t Chinese? I thought maybe I could just be a Chinese person who looks really, really white.

Then, it clicked.

What if I was a Chinese person who was really, really white? There must be a way around this regulation.

For the following three weeks, I spent dozens of hours trying to find loopholes across the system. I set-up new accounts, streamed from different apps, and used a VPN that said I was in Beijing. I once called up the customer helpline at Sina and tried to impersonate the thickest Beijing accent I could muster. The call center employee told me, "Sir, it is very clear to me that you are not Chinese."

(to be continued)

Read: How I Tried (and Failed) to Become an Internet Celebrity in Taiwan and China (2/2)

About the Author

Stephen Turban is a recent graduate of Harvard College and an alumnus of Jianguo Municipal Highschool. In high school, Stephen lived in Taipei as an exchange student; ever since, he has been writing about his time in Taipei, his experience's learning Mandarin, and his interest in organizations. Stephen's work has appeared in the Harvard Business Review, Slate, and has been cited by Hillary Clinton in speeches. Stephen currently works for McKinsey & Company where he tries to combine data science with questions about human and organizational behavior. In his free time, Stephen studies languages. Stephen is fluent in Mandarin and Spanish and is currently studying Vietnamese. You can follow him on Facebook and Weibo. You can also reach out to him directly at [email protected]

Crossing features more than 200 (still increasing) Taiwanese new generation from over 110 cities around the globe. They have no fancy rhetoric and sophisticated knowledge, just genuine views and sincere narratives. They are simply our friends who happen to stay abroad, generously and naturally sharing their stories, experience and perspectives. See also CrossingNYC.

Additional Reading

♦ Even In the Hardest Time, Engage and Listen

♦ Decoding the ‘Private Message’ Culture

♦ Japanese Photographer: Let the Beauty of Taiwan be Seen

This article presents the opinion or perspective of the original author / organization, which does not represent the standpoint of CommonWealth magazine.