China’s IC Ambitions

Big Money ≠ A Second TSMC

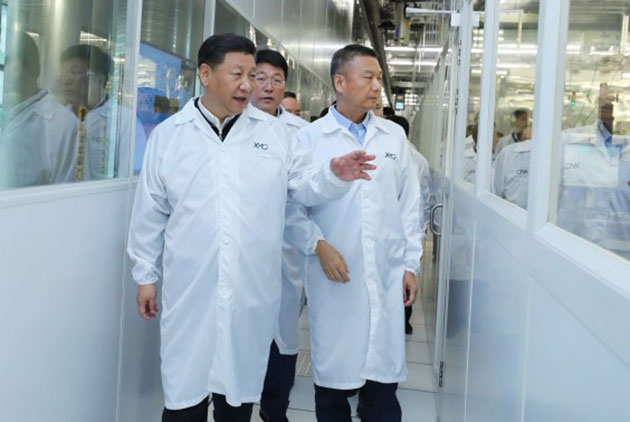

Source:AFP

China has shown a willingness to do whatever it takes to become an electronics superpower, including trading market access for technology. But the strategy has so far fallen short in boosting leading Chinese wafer foundry SMIC. Why is that?

Views

Big Money ≠ A Second TSMC

By Liang-rong ChenFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 648 )

“The United States is now ready to get tough on China,” the vice president of an American semiconductor company excitedly told a CommonWealth Magazine reporter by phone from abroad at the end of April.

“The previous few American presidents have all been weak toward China,” he said.

The Trump administration has accused China of stealing American corporate trade secrets, and his company has been one of the biggest victims.

“[People with the Chinese government] show up at our Shanghai office at night and tell us to open the door and then run off with information they took directly from our computers,” he says. But because the company is highly dependent on the Chinese market, it could only “suffer in silence” and quietly accept the intrusion.

This is a prime example of the darker side of a long-standing strategy at which China is particularly adept: swapping access to the Chinese market for technology.

A more common approach is for a foreign company to be forced to enter into a joint venture with a Chinese state-owned enterprise to “share” technology and nurture a future competitor.

In September 2014, for example, American chip giant Intel announced it was investing US$1.5 billion to acquire a stake in an IC design joint venture between Tsinghua Unigroup subsidiaries Spreadtrum Communications and RDA Microelectronics. Then in early 2016, it agreed to partner with Tsinghua University in Beijing on a venture to make chips for servers.

American IC design company Qualcomm Inc. even entered into a joint venture with a subsidiary of China’s state-owned Datang Telecom Technology Co. to design and sell smartphone chipsets in China, a venture that was given the green light by China’s antitrust regulator in early May 2018.

It also entered into a partnership with Huawei Technologies and Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC) in mid-2015 to form a technology company dedicated to developing 14-nanometer process technology.

For industries with some relatively mature technologies, the “access for technology” strategy has paid healthy dividends. The New York Times reported, for example, that the bullet trains China touts as being made at home with independent intellectual property rights actually used technologies from joint ventures with Japanese and European companies.

Wielding Its Power to Bridge the IC Gap

But in the semiconductor industry, a source of major concern to the Chinese government in which China runs a sizable trade deficit (of 1.2 trillion renminbi or NT$5.7 billion), progress in Beijing’s eyes has been slow despite a massive campaign to tilt the playing field in its favor.

This was evident at a forum for overseas scholars organized by the University of Science and Technology of China in Hefei.

Slides of 15 major Chinese electronic products were being projected on stage showing the “local content share” of each product’s core processor. For most of them, the percentage was zero, while the highest was the 22 percent share that HiSilicon Technologies and Spreadtrum had in communications chips for smartphones.

“What I want to tell everyone is that no matter how difficult the challenge, the logic of developing ICs is this: As a big country intent on rising globally, [the goal] cannot be achieved without the support of chips.”

“Without the support of ICs, the country’s basic security cannot be guaranteed,” she insisted.

The passionate speaker on stage was Liu Ming, a Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) member and a research fellow with the CAS Institute of Microelectronics. She is recognized in China as an authority on memory technologies and previously helped Chinese semiconductor maker Wuhan XinXin Semiconductor develop its technology.

In recent years, China has stunned the world with its heavy-handed global buying spree of semiconductor companies that was initiated in June 2014 when China’s State Council approved the “Guidelines for the Promotion of the Development of the National Integrated Circuit Industry.”

Aside from setting up a fund for the industry’s development, the “Guidelines” stressed the cultivation of talent as another priority and established what it called “exemplary microelectronics institutes” at 25 major academic institutions, including the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing University and Tsinghua University.

The program got instant results, with Chinese scholars at the very least experiencing a dramatic rise in recognition in international semiconductor research circles.

According to Liu Ming, Chinese authors had no more than 200 articles published over the past 30 years in two of the most authoritative journals in the field – Electron Device Letters and Transactions on Electron Devices. But in 2017, Chinese scholars accounted for about a third of the articles in the two journals.

After Four Years, Still Not Much Progress

The “China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund” is China’s first attempt at using something akin to a private placement approach to raise funds and support an industry, rather than providing subsidies financed by tax receipts or special deals on land. So how successful has it been over the past four years?

A semiconductor industry veteran who has long studied the Chinese market said China’s chip market remains in its “early” stages, with technology that remains far behind that of the world’s leaders.

Within the industry, the technology gap is the smallest in the IC packaging and testing sector because it has the lowest technological threshold to entry. China has made considerable inroads in the field, especially after Chinese IC packager Jiangsu Changjiang Electronics Technology Co. acquired Singapore-based rival STATS ChipPAC in 2015. The company has since become the third largest IC packager and tester in the world.

In the IC design field, Huawei subsidiary HiSilicon ranked seventh among the world’s fabless IC design companies in 2017 with revenues of US$4.7 billion.

“This company is very competitive,” says the semiconductor veteran, praising the company’s Kirin series of smartphone chips as “very advanced.” The timing of its introduction of chips made with the 7-nanometer process has nearly put it on a par with the industry leader, Qualcomm.

As for China’s biggest pure-play wafer foundry, SMIC, it has drawn attention after former TSMC executive Liang Mong-song took over as SMIC’s co-chief executive. The notorious Liang was suspected of leaking TSMC’s trade secrets to Samsung earlier this decade and helping the Korean electronics giant overtake TSMC in 14-nm chips.

Goldman Sachs technology analyst Donald Lu said at a conference last year that contract chipmaking has the highest technological threshold of any semiconductor discipline. “SMIC is having a hard time chasing after TSMC and UMC, and their profit margin is slim,” Lu said.

It’s no surprise then that SMIC has been unable to narrow the technology gap with TSMC in the nearly 20 years it’s been in business. Industry insiders believe the Chinese foundry is at least five years behind TSMC, the world’s biggest pure-play chipmaking foundry, because of two main factors.

Factor No. 1: Heavy Competition

Why is it that several well-established “national technology companies” heavily supported by China’s government, such as Huawei and BOE Technology Group, have made it big, but SMIC seems to be standing still?

It’s because “[SMIC] cannot capitalize on China’s home market advantages,” says Chu Wan-wen, an adjunct research fellow with Academia Sinica’s Research Center for Humanities and Social Sciences.

The “first pot of gold” earned by Huawei and ZTE came from China’s highly protected domestic market that had relatively low technology requirements, Chu says. Only after they built strength at home did they venture into overseas markets.

The semiconductor industry supply chain, however, is highly globalized, and a majority of customers in the industry are not that price sensitive, making it hard for SMIC to leverage the home-market advantage the way Huawei and others have.

For evidence of this, look no further than the explosion in demand for semiconductors for cryptocurrency mining applications in the last year.

Even though all bitcoin mining equipment producers are Chinese companies led by Bitmain Technologies Ltd., local wafer foundry heavyweight SMIC has not reaped any benefits.

Orders to satisfy the massive Chinese demand have nearly all flooded across the Taiwan Strait to TSMC, which said 9 percent, or about US$750 million, of its revenue in the first quarter of 2018 came from the cryptocurrency mining sector, an amount nearly equal to SMIC’s total sales in the quarter.

At SMIC’s first quarter earnings conference, analysts pushed SMIC executives on how much bitcoin semiconductors will contribute to the company’s revenue in the future.

Liang Mong-song essentially sidestepped the question, saying only that SMIC was hoping to get involved in this field.

SMIC has come up empty so far because its manufacturing technology falls well short of the cryptocurrency mining sector’s needs.

The ASIC (application-specific integrated circuit) chips used in the mining industry require massive computing power and have been commonly made with the 28-nm process at a minimum. But while SMIC claims to be mass producing with the 28-mm process, it has been unable to improve its yield rate, removing it from customer consideration.

The stakes have even grown higher as bitcoin’s price has plunged, with systems run on 28-nm chips becoming less profitable. Even new-generation mining chips are quickly losing their luster as companies look to adopt the 16-nm or even more advanced processes.

Liang admitted at the earnings conference that because SMIC’s 28-nm R&D process had dragged on for too long, it missed out on many opportunities.

Factor No. 2: Pulled Down by Politics

China is intent on mobilizing its national strength to develop semiconductors, but that has led to a structural constraint – the traditional government system.

Academia Sinica’s Chu explains that the “East Asian model” of the past relied on central government agencies, such as Taiwan’s Council for Economic Planning and Development (now known as the National Development Council) and Ministry of Economic Affairs, Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and South Korea’s Ministry of Strategy and Finance, dealing directly with companies.

In China, however, industrial policy has followed a pattern of “the central government making policy and local governments executing it” because of the country’s vastness. Local authorities, in turn, regularly “compete on growth,” leading to chaos, with each city and province offering big incentives to attract semiconductor foundries.

SMIC has two 12-inch wafer foundries 1,000 kilometers apart in Shanghai and Beijing and an 8-inch wafer foundry in both Shenzhen and Tianjin. The big distances between the sites has made it hard to form semiconductor clusters and complicated their management.

Having shareholders with different state-run enterprise backgrounds who have their own opinions and people has also evolved into constant infighting between internal factions. With so much strife, SMIC’s performance has naturally suffered.

“Semiconductor manufacturing is especially difficult and requires people who are willing to burn money and provide support for long periods of time without interfering,” Chu says, contrasting SMIC’s situation with the way TSMC was founded that was key to the Taiwanese foundry’s success.

The most important element, she says, was that it had an outstanding leader with an entrepreneurial spirit in TSMC chairman Morris Chang, and the same has been true for Huawei, and its founder Ren Zhengfei.

“[The leader] has to be able to be able to make entrepreneurial decisions when there are many unknowns,” Chu says. “That’s what’s most difficult.”

Translated by Luke Sabatier.

Additional Reading

♦ Snatching Apple Orders: TSMC’s Unsung Weapon

♦ Taiwan Shouldn’t Feel Inadequate Compared to China

♦ TSMC Takes on Samsung