Major Advocate for Liu Xiaobo’s Nobel Prize

Yesterday’s Red Guard Has Something to Say to Today’s Taiwan

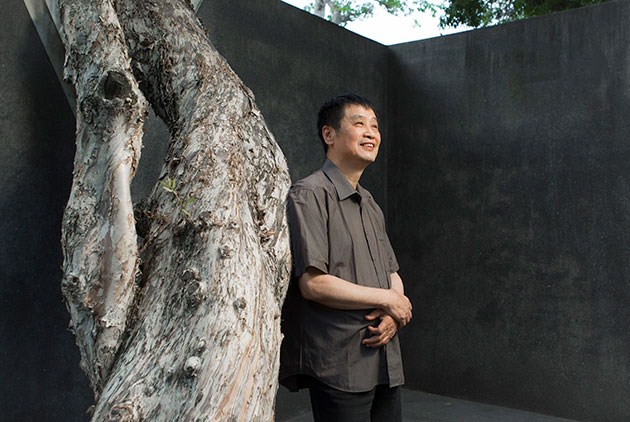

Source:Justin Wu

Xu Youyu was one of the first signatories of Charter 08, a manifesto drafted by the late Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo advocating that China institute a modern political structure of democracy, separation of powers, and constitutional government under the universal values of freedom, equality and human rights.

Views

Yesterday’s Red Guard Has Something to Say to Today’s Taiwan

By Kai-Lin Wuweb only

Xu Youyu played an instrumental role in the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Liu Xiaobo. In September of 2010, Xu wrote a letter appealing to the Nobel Prize Committee to award the Nobel Peace Prize to the Chinese dissident.

In June of 2010 he teamed up with fellow scholars to draft the Civic Commitment appeal in hopes of spreading civic consciousness throughout the Chinese population. In May of 2014, he was arrested for participating in a symposium on the Tiananmen Square protests and crackdown on the eve of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the events, and subsequently released from detention that June. From 2015 through the first half of this year, he has been a resident scholar at the renowned New School in New York City.

Today, Xu Youyu, known for his frank criticism and reflection, is considered a member of the liberal school of political philosophy. A true believer in Chinese socialism half a century ago, in recent years he has come into further prominence as an authority of scholarship on the Cultural Revolution.

No Longer a “Reformer” - Just a Historian

This July, Xu lectured in Taiwan at the invitation of the Lung Yingtai Cultural Foundation. During the post-presentation question-and-answer period, Lung posed the following question to Xu: “Suppose two people appeared before you right now: O ne is a confident, arrogant Chinese intellectual and advocate of Chinese [authoritarian power], who believes that the current state of affairs is proof that the path China has taken is the correct one, and that democracy is a failure and a mistake; the other one is a self-doubting Taiwanese person who, witnessing the rise of China, has begun to second guess the democratic path in which he has invested so much over the years. What would you say?”

To this, Xu’s initial response was a terse, “It would tear my heart apart.” Instead of breaking into a long discourse and criticism as a scholar might be expected to do, Xu’s response was succinct and to the point: “If I encountered such Taiwanese people, I would tell them my personal experience. And if they had any kind of conscience, I would be able to move them.”

Disillusioned Former Red Guard Leader

The year 1968 saw the rise of student movements around the globe. From China to the U.S., France and Japan, they had several things in common: opposition to authority, the establishment, and capitalism.

However, while student movements were on the rise in the Western world, the militant movement of the Red Guards in the Chinese Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was losing steam. And the year 1968 would go down in Chinese history as for long series of crackdowns and arrests.

That year, high school graduate Xu Youyu was a Red Guard leader. Full of youthful passion, he counted his blessings for the opportunity to take part in this “new era of human history.” Facing those who questioned the Cultural Revolution, Xu reassured himself, saying, “You only see part of the picture; we see the whole. You see phenomena; we should know its essence.”

However, the deeper his involvement, the more he came to discover the darkness within and the disconnection with reality, steadily dismantling the political beliefs he once held.

From its inception, the Red Guard was never anything but a tool Mao Zedong used to take down his political enemies. After he successfully “struggled” Liu Shaoqi out of power, for Mao Zedong the Red Guard became a thorn in his eye that had to be eliminated. This made him treat them like garbage, sweeping them out from the cities when he launched the next movement of sending educated youths (知青) to work in the mountains and countryside. What he never anticipated was that this movement marked the beginning of the educated younger generation’s disillusionment with the ideals of Chinese socialism.

“We must admit that our generation was duped, and our ideals and passion were played,” wrote Xu Youyu in an essay entitled “My Final Assessment and Reflections on the Cultural Revolution.”

Photo: Lung Yingtai Cultural Foundation

Photo: Lung Yingtai Cultural Foundation

When Hens Were Worth More Than People

Xu was 21 years old in 1968. During the interview, he chuckled as he described himself as “an obsessed revolutionary” who deliberately sought out hardship. Only that way, he believed, could he “achieve big things.”

However, the poverty and backwardness of the Chinese countryside threw him for a loop. Farmers had little more than the four walls surrounding them. In order to make their home more presentable for a wedding, they would borrow suitcases from educated youths as props to place around the home, which they would return as soon as the groom’s party was out of sight. In one extreme example, a peasant family was so poor they only had one pair of pants among them, and only one person could wear them while the others hid in the corner.

In some remote villages, a person made less for a day of labor than the cost of a single chicken egg. “The value of an educated youth’s labor was less than that of a hen,” recalls Xu.

The poverty of rural life forced Xu’s generation of educated youths to realize that that the supremacy of Chinese socialism they had been force fed was a myth.

A 30 year-old College Freshmen

In 1977, following the conclusion of the Cultural Revolution, Deng Xiaoping’s decision to reinstate university examinations marked a turning point in Xu’s life.

Then 30 years old, an advanced age for a student, Xu and his wife, pregnant with their first child, registered together for the national university entrance examinations. To everyone’s surprise, she was accepted to university, while he was not. “I was sure of myself, and everyone around me thought I would get into university, yet I didn’t make it,” Xu recalls. “I was so embarrassed that I didn’t want to show my face. My wife got into university, and I had to remain an ironworker.”

However, Xu’s rejection from university was not due to academic shortcomings. Back then, all students had to undergo a “political review” to determine if they would gain admission to university, and one’s family background outweighed test scores. Anyone falling under the Five Black Elements for being deemed a landlord, rich peasant, counter-revolutionary, bad element, or Rightist, was barred from admission.

Later, at Deng Xiaoping’s insistence, qualified students barred from admission due to their family background were given another chance, and Xu Youyu enrolled in the Mathematics Department at the Sichuan Normal Institute. In 1979, he was accepted into the Chinese Academy of Sciences Research Institute. Upon completing his Master’s degree, he stayed on to work at the Research Institute of Philosophy, commencing his career in academic research.

For many educated youths of his generation, the Cultural Revolution was a lost decade of their lives, in which educations were wasted and promising futures were tossed asunder. Yet, paradoxically, the Cultural Revolution gave Xu the opportunity to explore a vast amount of classic Western scholarship in political science and sociology, which would subsequently nurture his academic research.

Three Life-changing Classics

While the Chinese Communist regime exercised thought control over the population, it nonetheless hoped that high-level party cadres could understand the latest trends in Western thinking. This desire led the party central to invest extensive sums of money to mobilize a large collection of scholars to introduce Western literature through Chinese translations.

After the Cultural Revolution broke out, these tightly controlled “banned books” in their original languages found their way onto the market, prompting many educated youths to begin reflecting on both the Cultural Revolution and the Red Guard movement. This triggered a reading movement, and the banned books helped deepen their skepticism and heighten their criticism of the Mao Zedong myth.

The first book that had a profound impact on Xu was former U.S. President Harry S. Truman’s memoir. In the book, Truman’s detailed recounting of the Korean War completely burst the lies Mao Zedong had built around the war that all Chinese believed at the time. Mao had claimed that imperialist America intended to use Korea as a springboard for invading China, and that China had dispatched a volunteer force to counteract American imperialism and defend justice.

“If China could make up such egregious lies about that, then it could just as easily lie about other things. So I began to realize that I was living in a systematic lie,” recounts Xu.

American journalist William Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich made Xu realize that the movement of sending educated youths to work in the highlands and countryside was not a grand strategy originated by Mao Zedong, but one that had previously been seen in Germany under Hitler. So China actually lagged behind Hitler on its own road to Fascism.

Former Yugoslavian Vice President Milovan Djilas’s book, The New Class: An Analysis of the Communist System, played an even bigger role in shattering Xu’s generations’ illusions about socialism. Djilas reserved particular venom for his criticism of those who promoted the socialist movement in the name of resisting the exploitation of the people by landowners and capitalists, only to form a new privileged class upon taking power.

Looking at the face of politics in China today against the history described in these classic books is likely to evoke a strong sense of déjà vu, as history is always repeating itself. The generation of educated youths whose illusions towards Chinese socialism were shattered subsequently became prime movers of the country’s opening and reform policy. Accordingly, people entrusted this generation of young intellectuals to enact real change in China once they achieved positions of leadership.

Photo: Lung Yingtai Cultural Foundation

Photo: Lung Yingtai Cultural Foundation

Either Heroes or Scoundrels

Following Xi Jinping’s ascension to power, “educated youths” has once again become a popular keyword. Given Xi’s personal experience as an educated youth, many people have held fanciful notions towards him and “governance by educated youth,” believing that his experience working shoulder-to-shoulder with China’s grassroots citizens gave him better insight into the realities of society. Xu was the first to go up against the wall of lopsided public opinion and voice his dissent.

“Decades ago, the renowned Chinese theorist Li Zehou foresaw that the generation of educated youths would one day be in power. But in his view, this generation would either become a standout generation of heroes for the ages or a bunch of heartless scoundrels. Unfortunately, in my estimation, they turned out to be the latter and not the former,” laments Xu.

In Xu’s view, the background of today’s Chinese leadership as educated youths has had no positive impact on their political leadership. “They worship Mao Zedong; a little Mao Zedong lives in each of their hearts… There is no reason for us to see governance by educated youths as a positive element for China’s political development,” he adds emphatically.

Xu is pessimistic, even hopeless, about the current political situation in China. At the conclusion of the Cultural Revolution, everyone thought such an historical tragedy would never happen again. Yet today the Cultural Revolution is back in China, becoming reality once more. “China’s leaders are imitating the Cultural Revolution, and they want to be the second Mao Zedong,” opines Xu.

Today Xu sees himself as an historian. And he wants to tell those younger than himself how such a giant leap backwards and such a dark period could have taken place. And why such a frightening tragedy for humanity is about to play out once again.

Translated from the Chinese Article by David Toman

Edited by Shawn Chou

Additional Reading

♦ Yu Ying-shih: Intellectuals Must Speak Up for the Poor

♦ Liu Xiaobo: I Have No Enemies: My Final Statement

♦ Does the KMT Still Have a Cross-Strait Role?