Taiwan's Health Care Crisis

Surgeons the New Endangered Species

Source:CW

When a disaster occurs in Taiwan, medical workers respond with passion. But once the adrenaline wears off, they face an even more real challenge – a flawed health insurance system – that is leading to shortages in critical medical fields.

Views

Surgeons the New Endangered Species

By Ming-Ling HsiehFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 576 )

When colored powder blown into the air at a Formosa Fun Coast water park concert exploded in flames, nearly 500 people were sent to emergency rooms around Taiwan with severe burns. Hospitals rushed to mobilize all of their medical workers to prepare for the onslaught of patients.

Among those mobilized were plastic and reconstructive surgeons, who would spearhead the front-line rescue effort.

"Over 20 plastic surgeons were called in, and that doesn't include the hospital's own attending physicians," says Ming-huei Cheng, a reconstructive surgeon at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital's Linkou branch and the hospital's vice superintendent.

On the night of June 27 when the accident occurred, the Linkou branch treated more than 40 patients on an emergency basis, cleaning them in sterile water, intubating them, giving them intravenous infusions and even performing fasciotomies (cutting through the fascia to treat the loss of circulation to tissue or muscle and prevent the need for amputations). The patients were taken care of in three to six hours and then admitted as inpatients.

Many plastic surgeons remained at the hospital for days, surgically debriding burn victims every day to remove dead and contaminated material from their wounds.

Bare Bones Staffing

Taiwan's health care institutions have a combined 250 to 300 reconstructive surgeons responsible for treating burns, reattaching fingers, removing head and neck tumors and reconstructing mouths and breasts in patients who have suffered from oral and breast cancer. These responsibilities are in addition to the more common fields of medical cosmetics and plastic surgery.

Though the numbers are adequate at present, fields that involve long hours and considerable manpower and supplies, such as burn treatment and microsurgical reconstructive surgery, have always been at risk of being understaffed and shortchanged by reimbursements for care paid by the national health insurance system.

Plastic and cosmetic surgery and medical cosmetics, on the other hand, which feature high demand, low risks and high out-of-pocket fees from patients (because most procedures are not covered by national health insurance), have proved increasingly attractive to young people studying medicine.

"How many plastic surgeons stay at hospitals to practice their craft? Most of them go into cosmetic surgery," said Taipei Mayor Ko Wen-je, a physician by trade, in an interview in early July. "Nobody wants to go into critical care, and the reason is very simple -- It's different work and different pay. You do more work and get paid less."

In fact, the manpower strain and predicament facing medical personnel in Taiwan has always been a problem of distribution imbalances rather than an overall lack of health care workers.

A closer look at the distribution of medical personnel reveals that Taiwan faces serious manpower problems in five critical medical specialties.

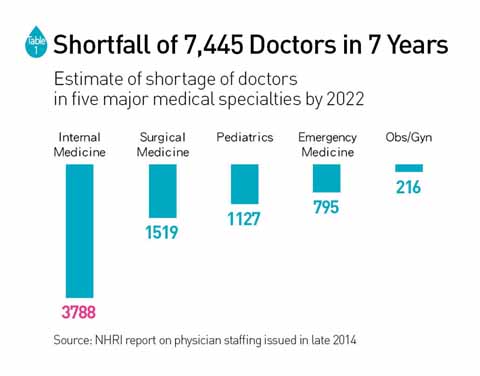

A study by the National Health Research Institutes (NHRI) at the end of 2014 projected that by 2022, Taiwan will face a shortage of more than 7,000 people in the areas of internal medicine, surgical medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics and emergency medicine. Surgical medicine alone will be 1,500 people short. (Table 1)

Chao A. Hsiung, the director of the NHRI's Institute of Population Health Sciences who was responsible for the study, explains that the main cause of the looming doctor shortage is Taiwan's aging population, which has caused a growing demand for medical services. But underlying problems such as long working hours and frequent medical disputes are also taking a serious toll on younger doctors' willingness to enter the five fields at most risk of being short-staffed.

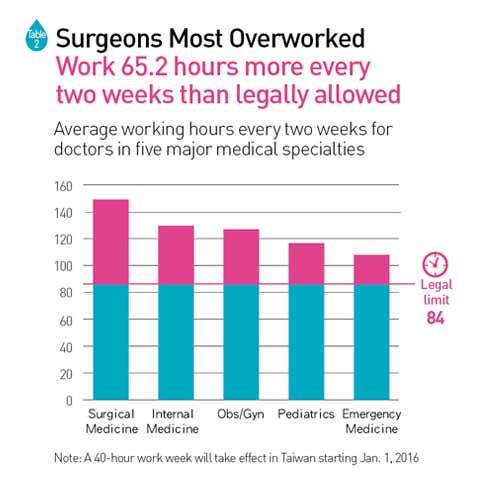

The study found that surgeons work an average of 149 hours every two weeks, far exceeding the maximum 84 hours stipulated by law. (Table 2)

These excessively long working hours and low reimbursement amounts from the national health insurance system for services provided are driving people away.

National Cheng Kung University Hospital oral and maxillofacial surgeon Ken-chung Chen contended in a speech in October 2014 that the low reimbursements paid to medical providers was one of the main contributors to the "four major-empty" phenomenon, referring to the declining manpower in internal and surgical medicine, pediatrics and obstetrics and gynecology (but not including emergency medicine).

He lamented that live-saving cardiac massages seem to be worth less than foot massages, which in Taiwan generally costs NT$500 to NT$600 and can go as high as NT$1,000 to NT$2,000. A 10-minute cardiac massage is only reimbursed 755 points from the NHIA, and the payment often ends up lower once the point values are discounted and converted into Taiwan dollars.

"Things have to be fast, good, and cheap. Is that even possible? Through the strenuous efforts of our medical personnel, our health care services have nearly achieved this mission impossible," Chen said.

Chen was referring to a national health insurance system that reimburses hospitals with point amounts for services provided, then determines how much those points are worth based on an overall budget ceiling. If too many points have been awarded, and valuing them at NT$1 per point would exceed an overall budget ceiling, then the point values are discounted to fit them within the budget, a fairly common occurrence that only further reduces doctors' incomes.

Chih-chun Yang, a surgeon at the Chiayi branch of Taichung Veterans General Hospital, went a step further, describing the current crisis as headed toward a "mass extinction of surgeons."

Of the 1,100 medical students who graduate every year, only about 10 percent are willing to take the examination for a surgical license. But the actual number of practicing surgeons in Taiwan fell by 102 in 2012.

Yang says the biggest reason behind the disappearance of surgeons, aside from the growing lack of trust between doctor and patient, is a serious "food shortage," the term he used to describe the low reimbursements paid to hospitals for surgical services.

A heart bypass surgery, for example, requires a team of at least 10 people and takes six to eight hours. For the first bypass graft, the national health insurance system pays 38,273 points, but that point value gets discounted and then split among the 10 people on the team. For a second graft, the point value is only one-fifth that of the first graft; the third graft pays less than one-fifth of the first graft; and the fourth or subsequent grafts are free.

"If you are a construction company and the government asks you today to build overpasses and offers you full price for the first one and 80 percent off for the second and third ones, and asks you to do the fourth one and after out of the kindness of your heart, would you take that deal?" Yang wondered.

As Taiwan’s health care environment deteriorates, many doctors warn that long working hours, constant disputes and low reimbursements has turned surgeons into an endangered species.

As Taiwan’s health care environment deteriorates, many doctors warn that long working hours, constant disputes and low reimbursements has turned surgeons into an endangered species.

Shao-jung Li, a cardiovascular surgeon at Taipei Municipal Wanfang Hospital and the deputy director of the hospital's Department of Surgery, sees the reimbursement scheme for bypass surgeries as shortsighted because it fails to account for the fact that multiple bypass surgery patients are usually high risk, making the operations more difficult.

Ultimately, the longer this system has been in place, the fewer the number of people willing to cope with the high stress of such difficult surgery.

Taking the Easy Way Out

"An even bigger problem than the shortage of health care resources is their inequitable allocation," Yang says. "Think about it. All things being equal, nobody wants to do low-reimbursement, high-risk procedures. At a critical moment in the future, you may not be able to find a doctor to operate."

Within the surgical field, in contrast to cardiac surgery, thoracic surgery and other secondary specialties, there is generally no problem filling the openings at hospital for attending plastic surgeons.

Upon closer inspection, however, there are more desirable and less desirable sub-specialties within the plastic surgery field, and burn care has always been seen as a less desirable "money-losing" sub-specialty because of the substantial manpower and resources needed to care for burn victims.

Burn victims must have their dressings changed once or twice a day, an undertaking that requires an average of six to eight medical workers each time. At least three to four surgeons are needed for every debridement and skin grafting procedure so that they do not take too long. For patients with burns covering large parts of their bodies, they have to be given 1,000 cc of intravenous fluids an hour and have their gauze or cloth bandages changed frequently.

Even if the disaster at the Formosa Fun Coast park was an extreme case and not as many burn specialists are needed under normal circumstances, the NHIA says its reimbursements to health care providers for burn wards are higher than for intensive care wards. But doctors still believe that burn therapy remains a money-losing proposition, and several privately run hospitals are unwilling to support burn centers.

Another endangered surgical specialty is microsurgical reconstructive surgery, a discipline that has a wide range of applications, including reattaching fingers, repairing nerve damage from external injuries or reconstructing mouths in oral cancer patients or breasts in breast cancer patients.

Other disciplines also need the help of reconstructive surgeons. In liver transplants, for example, reconstructive surgery is used to reconnect the hepatic artery, which supplies a quarter of the liver's blood flow.

But David Chwei-Chin Chuang, a plastic surgeon at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital and president of the World Society for Reconstructive Microsurgery, says the field has suffered a huge outflow of doctors. Of the 128 reconstructive surgeons trained at the Linkou branch of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital over the past 36 years, only 16 percent have stayed on, creating a major fault line in the system. Of the four plastic surgeons who became attending physicians at the hospital this year, not one is interested in specializing in reconstructive microsurgery.

Chuang attributes the problem to the convergence of a few main factors: long working hours, the difficulty of the job and, as with many other surgeons, the lack of reasonable reimbursement rates from the national health insurance system.

In calculating the income and working hours of Chang Gung's plastic surgeons, Chuang discovered that reconstructive surgeons average 312 minutes per surgery, compared with 159 minutes for plastic surgeons and 151 for general surgeons. But average income per minute was the lowest of the three categories of surgeons at NT$187 per minute, earning the field a reputation as another money-losing medical discipline.

Chuang worries that this interruption in the talent pipeline will leave doctors with inadequate training and experience, negatively affecting the quality of care received by patients needing microsurgical reconstructive surgery in the future.

Faced with paltry reimbursements for the national health insurance for such surgeries, hospitals and doctors are taking the easy way out and focusing on better-paid niches that pose less risk.

Wanfang Hospital's Li says that in 2014, many cardiovascular surgeries were incorporated into "diagnosis-related groups," in which a fixed reimbursement is paid by the national health insurance system for the same ailment. The move has influenced how doctors treat their patients.

If deep vein thrombosis is treated aggressively, for example, an operation may be needed to remove the blood clot and apply a thrombolytic agent, or even install a stent or balloon to expand the blood vessel. The procedure can effectively eliminate the clot and prevent side effects, but it often costs more than the amount reimbursed under the DRG program.

The idea of "losing money on each procedure" has led many doctors to simply offer patients a thrombolytic agent to take orally rather than performing surgery.

"The DRG system has led to many patients being unwittingly treated as a human ball," Li says. He believes the problems he experiences are simply the tip of the iceberg and that other specialties face similar predicaments.

The NHIA reimbursement schedule profoundly influences the choices doctors make and resource allocations. After a 20-year run, the national health insurance system has reached the point where a thorough review of the imbalances in Taiwan's medical manpower can no longer wait.

Translated from the Chinese by Luke Sabatier