Rewriting the Final Chapter of Life

The Need to Let Go

Source:Domingo Chung

When is it time to say goodbye to loved ones? Taiwan has grappled with the question at great expense, resulting in considerable medical futility in end-of-life care.

Views

The Need to Let Go

By Whitney HuangFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 560 )

Medical technology breakthroughs are occurring with increasing frequency, but many in Taiwan are wondering if they truly go the extra mile to help patients "live" or simply drag out the painful process of dying?

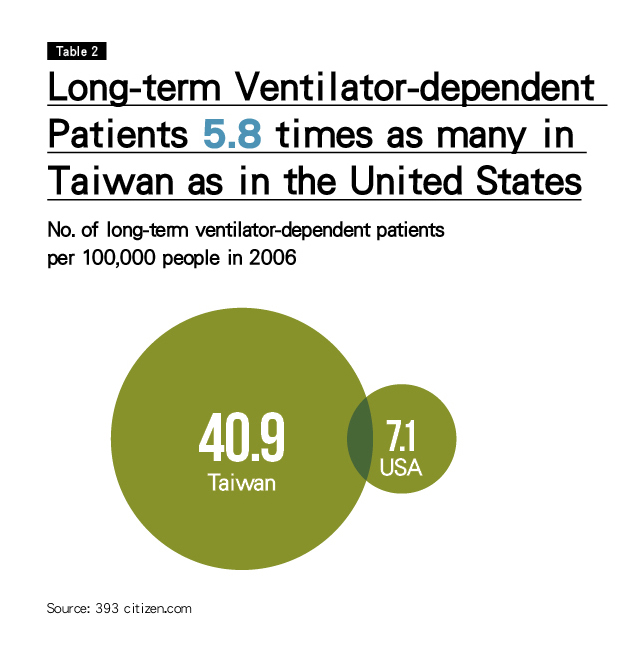

Taiwan has the highest density of intensive care unit beds in the world, with at one point 5.8 times as many people kept alive long-term on ventilators per 100,000 people as in the United States. Over half of Taiwan's doctors engage in "medical futility," including ineffective end-of-life interventions in intensive care wards , simply to avoid legal disputes, a practice that costs Taiwan NT$3.58 billion a year. Is the problem a matter of attitude or a system that's out of whack?

Scene 1: Outside a hospital's ICU, a male pediatrician arrives in a rush, insisting that the attending physician continue to treat his dying father.

The pediatrician learns, however, that his younger sister has decided to let their father go in peace and has signed a "Do Not Resuscitate" order. He calls her, and the two get into a big argument that he eventually wins. Though the attending ICU physician tries to explain that the patient cannot be saved, he has to resort to the so-called "death package," which means continuing to administer medicine and preparing CPR and electric shock treatment.

Scene 2: In a respiratory care ward, one bed after another is occupied by elderly people. Nearly every one of them is connected to a ventilator, unable to utter a word. The skin of some has turned dry and dark. The limbs of others appear deformed, their bodies twisted up and motionless.

In this quiet part of the hospital, the ventilators and their constant thumping sound exude far more energy than the elderly they are keeping alive. Some of the patients occasionally have their eyes open, but their blank, unfocused stares leave visitors feeling more despondent than if their eyes had been closed.

Remorse, guilt, distress. These should not be the main themes as a person's life comes to its end.

"You can't really know how much pain people are in if you think keeping them around is an expression of love. To call it filial or not filial, I really don't know how to describe it," says Chen Shew-dan, director of the non-surgical intensive care unit at National Yang-Ming University Hospital in Yilan. In her position for more than a decade, Chen has witnessed countless end-of-life tragedies that have left deep impressions.

When Chen, a devout Buddhist, left Taipei for the Yilan hospital, she didn't mention salary or benefits but did request setting up a Buddhist prayer room, hoping that the Bodhisattva would use its compassionate eyes to look after suffering souls.

The Arduous Last Mile

Growing breakthroughs in medical technology are challenging how people see their lives coming to an end, blurring the boundaries between the "here" and the "after" and making it hard for people to die even if they want to.

If your kidney functions have deteriorated, they can be put on dialysis; if your liver is bad, it can also be given dialysis. If you can't eat normally, you can be fed through a nasogastric tube or given intravenous injections. Can't breathe? You can be intubated or get a tracheostomy, or even be put on a ventilator. If your heart stops beating, you can be given an electric shock and then be put on an ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) machine.

In their publication "National Health Insurance," which took an in-depth look at Taiwan's medical practices and universal health insurance system, former Control Yuan member Huang Huang-hsiung and two co-authors wrote that many terminal patients in ICU wards were still having blood drawn, X-rays taken, or mucus extracted, or were even given kidney dialysis or ECMO therapy on the day they died.

"To patients, this is a form of torture and abuse. And it actually leaves the patients' family members with endless nightmares and horror," Huang wrote.

The medical community once estimated that ICU patients gain three kilograms before they die because their bodies swell from all the drug and other therapies they are given.

"The ICU has become an outpost on the way to the morgue," sighs Huang Sheng-jean, superintendent of National Taiwan University Hospital's Jinshan branch.

One of Taiwan's foremost head trauma experts, Huang Sheng-jean once believed in the all-powerful nature of technology and that a physician's responsibility is to do everything possible to save a patient. He even boasted that "patients in my hands don't seem to die."

He later discovered, however, that allowing patients to end their lives with dignity was even more important, and he became a strong advocate for hospice palliative care.

A veteran of many decades in the medical profession, Huang Sheng-jean observes that many doctors in Taiwan fail to understand that when an illness cannot be cured or a life cannot be saved, the responsibility of a physician is in fact to "accompany the patient in heading to the end."

"I don't know when it started that you had to cure 'organs' (as opposed to patients). Today, ICUs have become places where patients can be put even if they can't be healed simply to make money," he laments.

Taiwan's Depressing 'No. 1s'

Several indicators show how hard it is to travel the last mile of life in Taiwan. In fact, Taiwan leads the world in a number of depressing categories, a record that has successfully buried the dignity of many lives.

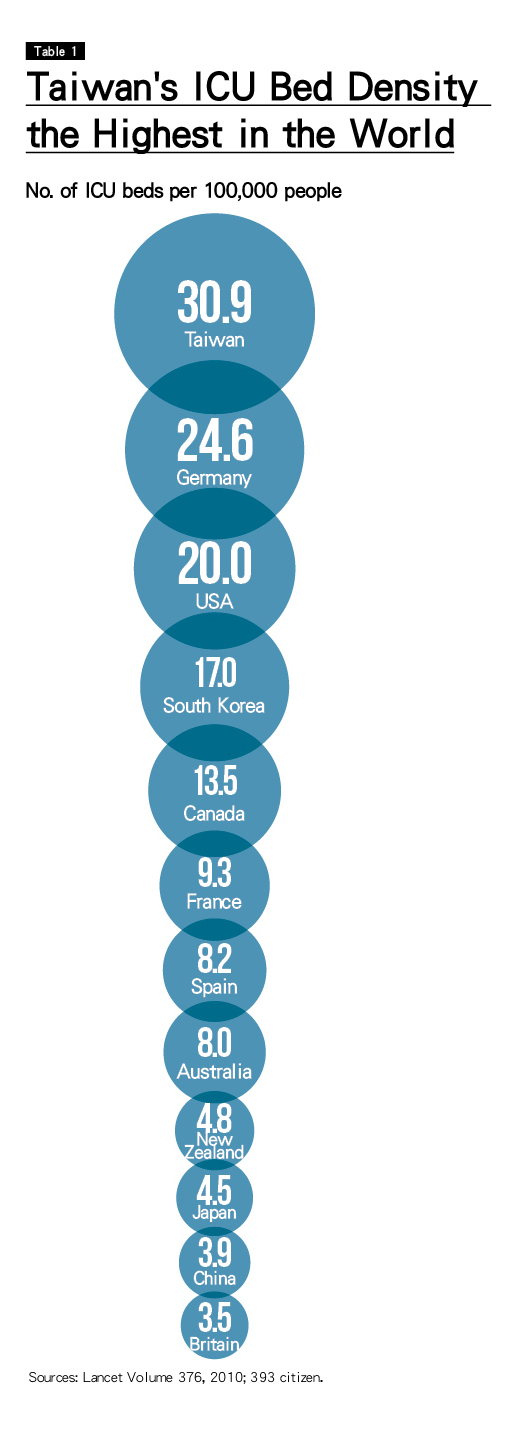

'Taiwan has the highest density of ICU beds in the world. There are nearly 31 ICU beds for every 100,000 people, 6.3 more beds per 100,000 people than in second-place Germany, about 50 percent more than in the United States and 7 times as many as in Japan. (Table 1)

'In 2006, the number of long-term ventilator-dependent patients (defined as being on a ventilator for more than 21 consecutive days) per 100,000 people was 5.8 times as high as in the United States. (Table 2)

Studies on the subject have found that 17-22 percent of total ventilation patients in Taiwan are on ventilators for more than 21 days, far higher than the 5-13 percent indicated in studies done overseas.

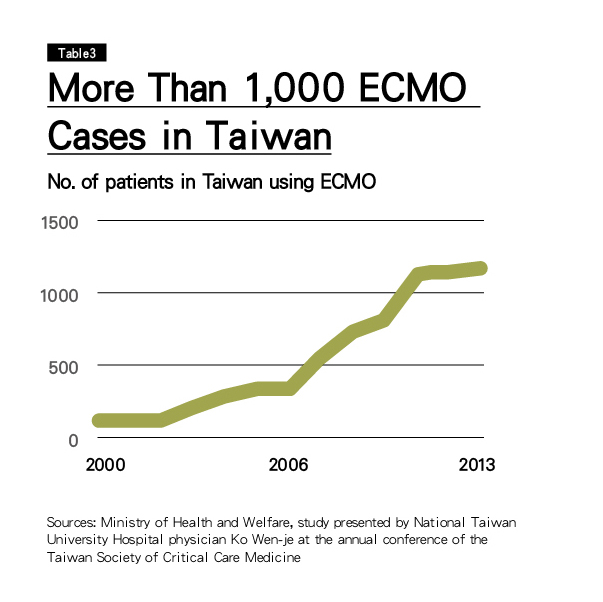

'Taiwan's use of ECMO machines is extremely high and not coming down. The United States has a population 13 times as big as Taiwan's, but, according to medical sources, ECMO machines are used an average 2,000 times a year in the U.S., only about double Taiwan's use of the machines. (Table 3)

A 2008 study published in the authoritative medical journal Lancet found that ECMO machine use in Taiwan from 2004 to 2006 was 50 percent of the total number of such cases around the world during that period.

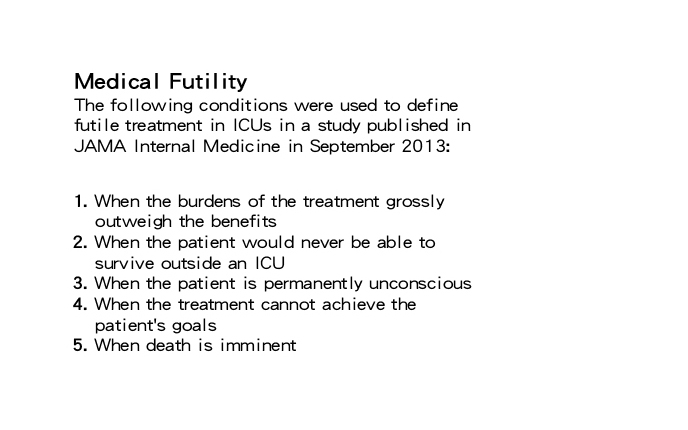

Much of this reflects what is described as "medical futility," but defining it precisely has been controversial. No absolute consensus, but a study in an American Medical Association journal has described treatment as being futile if the suggested therapy will only prolong the dying process without benefit to the patient or to others with legitimate interests. (See Definition)

To gain an understanding of how much "medical futility" exists in Taiwan's ICU wards, CommonWealth Magazine and the 393 citizen.com online platform teamed up to conduct a study and two surveys on futile treatment care in end-of-life interventions.

The first was an analysis of a database of millions of pieces of information provided by the National Health Insurance Administration (NHIA) for academic use to assess the actual degree of medical futility in end-of-life care in Taiwan.

The second was a random survey of Taiwanese residents on their attitudes and behavior in facing the end of their lives. (Survey 1)

The third was a questionnaire survey of Taiwan's critical care specialists to understand the factors driving physicians to engage in "medical futility." (Survey 2)

According to the survey of critical care specialists , the proportion of medically futile cases in Taiwan's ICUs ranges roughly between 17 and 20 percent.

'Medical Futility' for Too Many

That means that out of every five to six patients in Taiwan's ICUs, one is likely receiving futile end-of-life care.

Referencing existing studies, the 393 citizen.com classified futile care cases as those in which a patient died in the ICU after the patient's condition worsened during his or her first 72 hours in intensive care and could not be discharged. In those cases, medical intervention only succeeded in prolonging the dying process.

With that in mind, the group then estimated, based on information found in the database, that of the more than 42,000 people admitted to an ICU the last time they were hospitalized before dying, more than half (52.9 percent), or about 22,000, received futile end-of-life care, at a cost to the system of NT$3.58 billion.

But many suspect that the biggest generators of futile or inappropriate care in Taiwan are respiratory care wards (RCWs).

Keep People Alive for Money

Respiratory care wards have gained importance because of an NHIA plan in the early 2000s to use them to take the load off of ICUs, which did not have enough beds at the time. The idea was to take patients in ICUs who no longer had acute problems but had not yet been weaned off ventilators and transfer them to respiratory care centers or wards to continue their treatment.

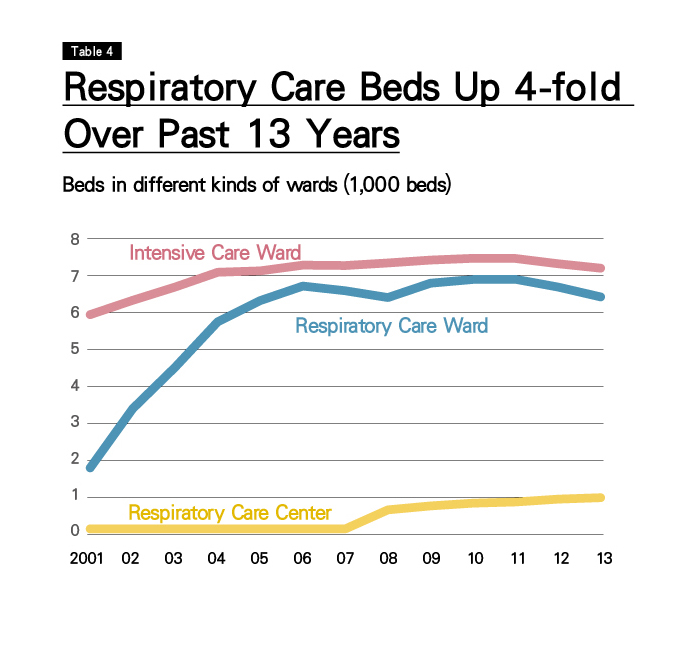

In the 13 years since, however, respiratory care ward beds in Taiwan have nearly quadrupled, and ICU beds have also increased substantially. (Table 4)

Over the past decade, Taiwan has averaged nearly 30,000 long-term ventilator-dependent patients a year, of whom 70 to 80 percent are in a vegetative state. Typically, over 80 percent of the patients are older than 60 years old, and of this group, nearly half (44 percent) are over 80 years in age.

According to figures for 2013, the average annual cost of "treating" long-term ventilator-dependent patients was 29 times as high as average per capita medical spending in Taiwan and required the national health insurance premiums of 34 people to be covered financially.

These numbers may be impersonal and dispassionate, but if the person lying on a bed attached to a ventilator was you, with limbs contracted and a nasogastric tube inserted for forced feeding, would you be willing to endure that?

CommonWealth Magazine asked members of the public that question in its survey and found that 80 to 90 percent of respondents rejected the idea of having their lives reduced to being kept breathing by a machine or surviving in a vegetative state.

But as hospitals have become more commercial, the dignity of life has often been compromised by financial realities.

"The respiratory care wards go all out to prolong the dying process and keep patients 'alive,'" says one veteran physician bluntly.

In a respiratory care ward in one small district hospital, an elderly man attached to a ventilator has limbs so badly deformed that he cannot have clothes put on him. Instead, he wears diapers and his body is wrapped in a sheet. He is as stiff as a terrifying wax figure, "breathing" silently.

One nurse confesses privately that the hospital's superintendent continues to "nurture" the elderly man, who was found collapsed on the street and does not have any known relatives, because the hospital can be reimbursed by the national health insurance system for his treatment.

Over the past decade, the NHIA has averaged NT$24.6 billion a year in reimbursements for ventilation treatment, but it eventually realized that the problem had become serious and has begun to cut reimbursement amounts, with spending on ventilator-dependent patients and related services edging lower in the past two years.

The Right to Die with Dignity

A multi-pronged approach is needed to confront the four major problems facing end-of-life care: patient suffering, family torment, medical ethics violations and medical resource waste.

Physician education must be overhauled to teach doctors to not see a patient's death as failure.

"Doctors need to attend to life and to death," says Huang Sheng-jean. He encourages all doctors, including those at the grassroots level, to discuss with terminally ill patients and their families what they would do if a decision on end-of-life care has to be made. This will help them get the necessary knowledge early in the process and help avoid the need for futile medical care.

The medical system as a whole should also review the role of intensive care units and remedial mechanisms so that terminally ill patients in ICUs don't have to die inhuman deaths.

"ICUs are not death centers. Only patients who can be saved should be admitted to them," Huang Sheng-jean suggests.

The NHIA may have already taken several steps to curb the inappropriate use of resources, but there remains considerable room for improvement.

The public must also courageously confront end-of-life issues and make plans in advance. For example, filling out a "living will" in advance to choose between hospice palliative care or life-sustaining treatment can leave individuals and their loved ones with no regrets when end-of-life decisions have to be made.

"Letting oneself go is wisdom. Letting others go is benevolence," says National Yang-Ming University Hospital's Chen, a strong advocate of "good dying" concepts.

She and many others are hoping that medical futility in end-of-life care will one day in the near future no longer deprive people of their right to die with dignity.

Translated from the Chinese by Luke Sabatier.