The 1% vs. the 99%

Taiwan's Vast Wealth Gap

Source:CW

Taiwan's rich-poor divide is at an all-time high, with the top 1 percent of income earners enjoying most of the gains of economic growth. The situation is unlikely to change unless Taiwan overhauls its outdated tax system.

Views

Taiwan's Vast Wealth Gap

By Hsiang-Yi Chang, Ting-feng Wu, Jimmy HsiungFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 549 )

After attending a high school reunion in mid-March, Huang Hsien-hung left with mixed emotions. An assistant manager for a foreign company in Taiwan, the 36-year-old Huang was invited to dinner along with seven or eight of his old classmates whom he hadnot seen in over a decade. Their host was"Hsiao Hu," and they met at his newly renovated 400-ping European-style villa in Taipei's posh Yangmingshan district.

After passing through the robust metal gate protecting the villa's main drive, the visitors were struck by the generous grounds, complete with an expansive garden, swimming pool, tennis court and basketball court. The latest model Ferrari was parked outside the villa, and a Bentley and Porsche SUV were tucked inside the garage.

The three cars combined were worth nearly NT$40 million. Huang quietly calculated that he would have to work another 20 years and not spend a penny on anything else to be able to afford the cars, and much, much longer to afford a Yangmingshan mansion.

"Unless I were to win the lottery, there is no way I could have this kind of life, no matter how hard I work," Huang couldn't help saying to Hsiao Hu. "If I didn't know you, I probably wouldn't realize how poor I am."

Despite being the same age and graduates of the same elite high school, the two men now have completely different lifestyles dictated by their incomes. While Huang made nearly NT$2 million in 2013, Hsiao Hu cleared NT$180 million from real estate deals alone.

The main factor deciding the gap in their earnings was not effort or hard work but having the capital necessary to make money by moving money around.

Biggest Class Divide in History

After Huang graduated from high school, he got into the business college of an elite university and then got a scholarship to study for an MBA in the United States. When he returned to Taiwan, he was quickly hired by a prestigious foreign company. In his five years on the job, he has not only paid off his student loans but also saved enough for a down payment on an apartment in the Taipei suburb of Muzha. In the eyes of many white-collar workers in Taiwan, Huang's ability to land a well-paying job and his own apartment through his own efforts puts him squarely in the "winners" column.

But Huang has nothing on his reunion host. Hsiao Hu was born into a wealthy family, and after graduating from college he took over his family's real estate portfolio worth more than NT$200 million. He first worked for a real estate agent for two years to build his knowledge of the property business and hone his instincts before investing full-time on his family's behalf. With the help of his family's contacts and financial support, and his bold use of leveraging, Hsiao Hu's real estate holdings have multiplied many times over the past seven years, and he has earned fame as one of Taipei's biggest investors.

"I've been pretty lucky. Interest rates have stayed low these past few years in Taiwan, and real estate prices have soared. Using money to make money has been relatively easy," Hsiao Hu said frankly. So much so that real estate investors like him in Taipei worth more than NT$1 billion are now far from scarce.

At one end of the spectrum a hard-working white-collar professional; at the other a big investor, or "rentier," who has used money to get wealthier. Huang and Hsiao Hu represent the "99 percent" and the "1 percent," respectively, and the gap between their incomes is only widening. Their story reflects Taiwan's gaping class divide and offers a concrete glimpse into the country's worsening income distribution.

The Top 1% Get 14% of the Income

Most Taiwanese agree that the rich-poor divide has grown wider in the recent past, but the government seems oblivious to the phenomenon. Many government agencies continue to propagate the idea that Taiwan's income gap is not serious relative to other countries in the world, and President Ma Ying-jeou has even suggested that narrowing the income gap is one of his administration's most significant achievements.

It may seem odd that the public and the government have such diametrically opposed perceptions of the issue, but the explanation is fairly simple. Official statistics fail to accurately reflect actual income distribution in the country.

The main tool used by Taiwan's Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS) to assess income distribution is a "survey of family income and expenditure." According to these figures, the difference in average incomes earned by the top 20 percent and bottom 20 percent or top 10 percent and bottom 10 percent of income earners has actually narrowed steadily since 2000.

But many academics who study income distribution, including Chinese Culture University sociology professor Hong Ming-hwang and National Development Council deputy chief Chen Chien-liang, contend that the DGBAS's income survey involves random sampling and can be easily skewed by high-income individuals who refuse to take part in the survey.

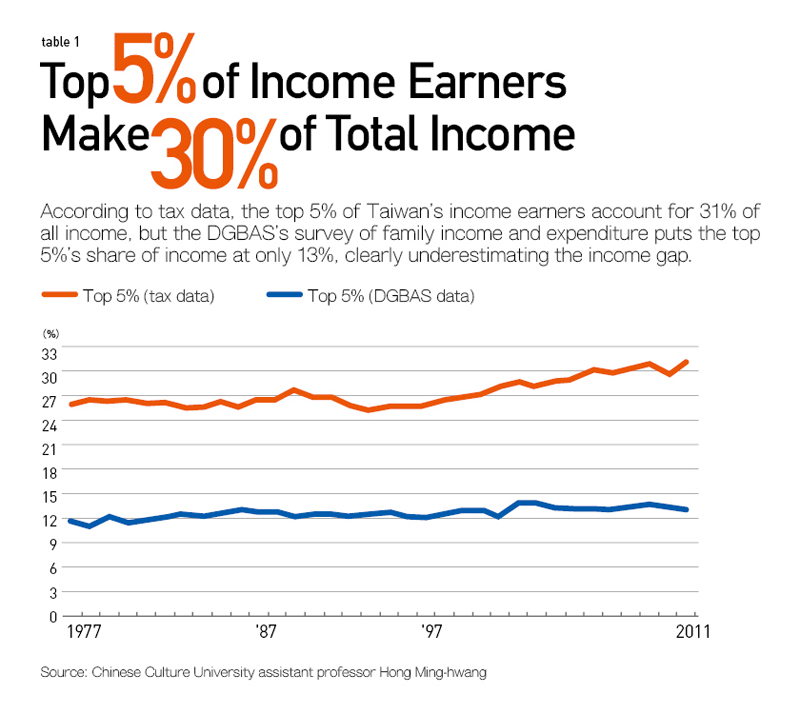

Internationally, researchers have preferred looking at tax data, which they consider more authoritative, to discern changes in income patterns, and if this standard is applied to Taiwan, then the country's top 5 percent of income earners account for twice as much of national income as official statistics would suggest. (Table 1)

Even more alarming, Taiwan's wealth is rapidly being concentrated in the hands of the wealthiest 1 percent at the top of the income pyramid.

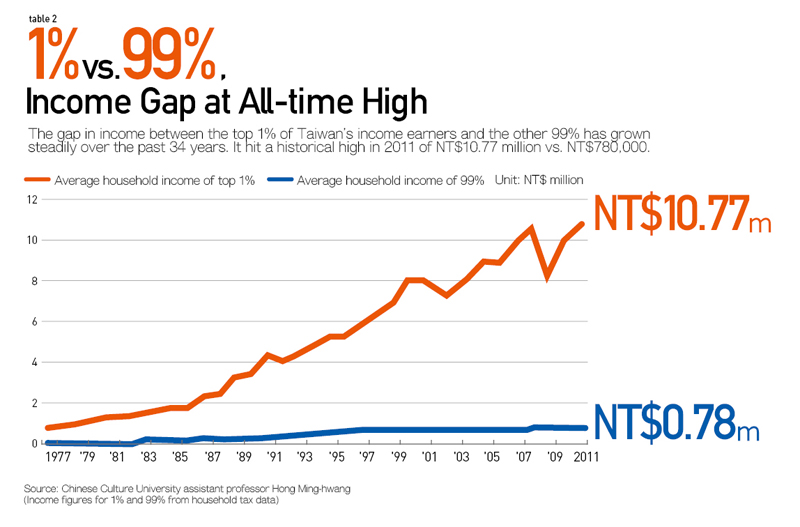

A study by Hong covering household tax data in Taiwan over more than 30 years through 2011 found that taxpayers with the top 1 percent of taxable incomes – a group of about 56,000 people – saw their incomes rise sharply every year, with the exceptions of 2001 and 2002 following the bursting of the dot.com bubble and in 2009 after the global financial meltdown. By the end of 2011, their average annual taxable income exceeded NT$10 million. The remaining 99 percent of taxpayers saw their incomes barely edge higher during the same period and had yet to average more than NT$800,000 a year. (Table 2)

The 1 percent at the top of the pyramid accounted for 14 percent of total taxable income reported in Taiwan in 2011, an indication that income is being disproportionately concentrated in the hands of the top 1 percent based on a comparison with other countries.

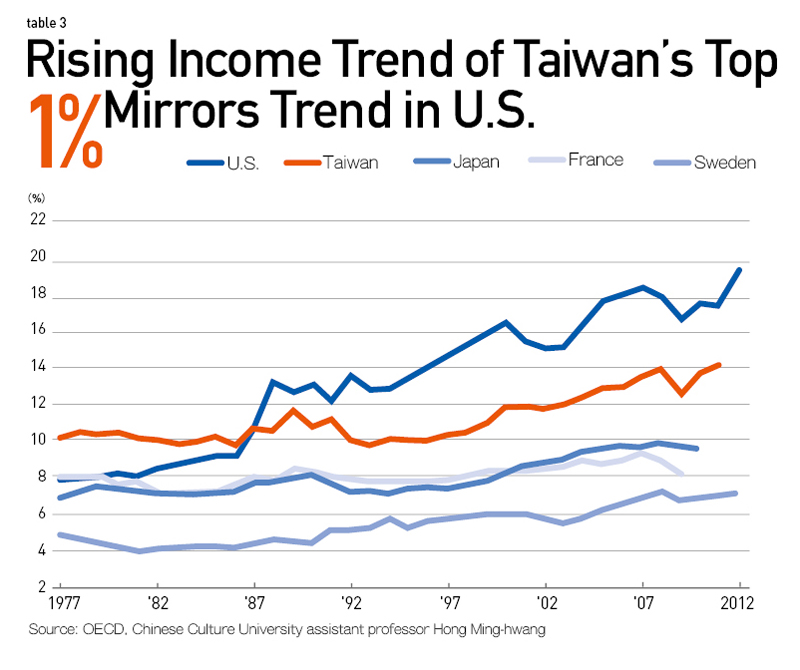

When Hong's results are stacked up against OECD data on the income of the top 1 percent in other economies, Taiwan emerges as the country with the second highest concentration of income at the top, trailing only the United States and finishing ahead of Singapore, Britain and Japan. (Table 3)

Hidden Wealth Hard to Track Down

Hong believes this is just the tip of the iceberg, because his study did not factor in income from property or stock sales. It is widely accepted in Taiwan that a significant portion of the top 1 percent come from big land-owning families or investors who rely on real estate or stock deals to amass wealth.

Just how much wealth is unclear, because under Taiwan's tax system, long criticized as being inequitable, capital gains on stock sales are not taxed, and those on property sales are taxed based on government-assessed values of land that are generally mere fractions of market value. As a result, the substantial earnings investors make from real estate and stocks are not listed as taxable income in personal income filings – "hidden wealth" that is left out of the tax data that research institutes depend on to gauge the extent of the rich-poor divide.

In other words, the concentration of wealth in the hands of the rich and the gap between rich and poor in Taiwan is in fact exponentially more serious than existing statistical profiles would indicate.

One statistical indicator does exist – a national wealth survey conducted by the DGBAS every five years – that at least offers a glimpse at the scale of this "hidden wealth" that tax statistics and income gap surveys simply cannot detect.

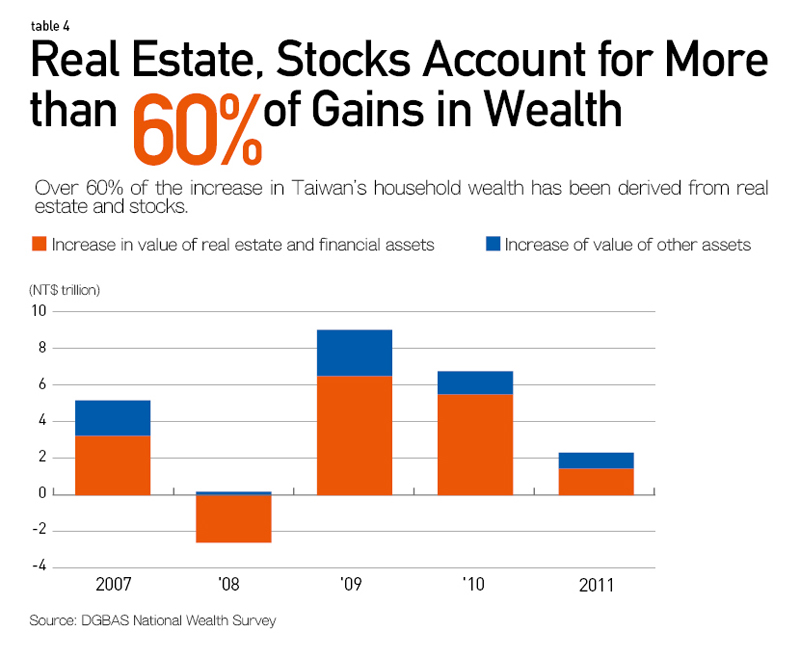

According to the most recent survey, more than 60 percent of the increase in wealth among Taiwanese households from 2007 to 2011, totaling NT$11 trillion, came from gains in the value of real estate and stocks. (Table 4)

In 2011 alone, the increase in household wealth from those sources totaled NT$1.49 trillion, a sum that accounted for 64.2 percent of the total gains but was invisible to the government's tax radar.

Soaring asset prices created NT$11 trillion in potential profits during the five-year period, a pie that was out of the reach of those trying to pay off the mortgage on their own apartment or salary workers who could not afford their own home.

Outdated Thinking on Tax Code

The growing concentration of income and wealth in the hands of a few reflects an international trend. The exacerbation of the rich-poor divide has triggered a widespread popular outpouring of grievances around the world, from the "Occupy Wall Street" movement in the United States to the "Occupy Central" movement in Hong Kong.

The growing stature of income inequality as a public issue was further illustrated by the heated debate that has bubbled up since Thomas Piketty, a professor of economics at the Paris School of Economics, published Capital in the Twenty-First Century last year.

The book argues that advanced economies led by the United States and Europe, have opted to print money and create greater liquidity to tide over problems when faced with financial crises or the more recent European debt crisis, undermining capitalism's self-adjusting mechanism to reshuffle the deck after an asset bubble bursts. That has resulted in global wealth continuing to gravitate toward a small number of rentiers, leading to greater inequality, the resurgence of hereditary wealth and an increased risk of social confrontation, Piketty contends.

But Taiwan's uneven income distribution is far more serious than seen in Europe or in other Asian countries, and if the "invisible wealth" from property transactions is added to the equation, it may be more serious than even in America.

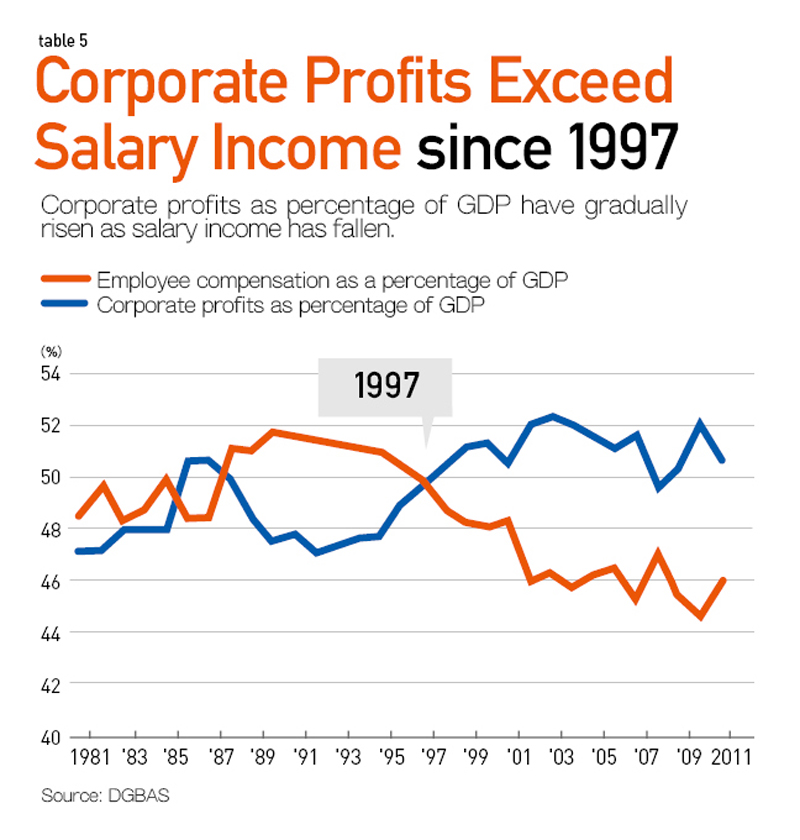

A key factor behind the dire situation has been Taiwan's inability to reform the tax code in step with the country's changing economic structure. Since 1998, wages and salary income as a percentage of GDP have fallen steadily while corporate profits as a percentage of GDP have been on the rise, but Taiwan's tax base continues to depend largely on salaried workers. (Table 5)

"Global wealth is being concentrated in the hands of rentiers. Aside from natural adjustments like market bubbles, the only other way to redistribute income is through the tax system," says Ho Chih-chin, a former finance minister and now an executive vice president at National Cheng Kung University, in an interview with CommonWealth Magazine.

"But in recent decades, as Western countries engaged in tax reform and increased taxes on capital gains, Taiwan moved in the opposite direction," he says.

Ho contends that faced with sluggish economic growth and stagnant investment in the past few years, the government has advocated the old formula of "tax cuts to spur the economy," not only leaving alone the inequitable system of taxation on real estate transactions– and by extension the fastest growing source of wealth in Taiwan – but even further reducing the inheritance tax. The result has been that for an entire decade, tax revenues from "salary income" have accounted for more than half of the total, while taxes collected on stock and property sales account for less than 1 percent of tax revenues.

"I'm afraid that this huge disparity between taxes on capital gains and taxes on salary income is unique to Taiwan," Ho says.

Exacerbating the problem is that efforts by many of Taiwan's industries to upgrade their operations have stalled, leading many companies to rely on their old formula of cutting costs rather than creating added value to stay competitive, making it nearly impossible for salary levels in Taiwan to rise.

Taiwan's obsolete tax system and slow pace of industrial transformation encourage a state of affairs in which wealth begets wealth through capital transactions, turning the country into a speculation paradise for the rich.

The Death of the 'Taiwan Miracle'

"The low costs and high profits involved in making money by moving money around have not just deprived the younger generation of opportunities for development and 'housing justice.' An even greater concern is that investment is focused on the equity and property markets rather than on industrial innovation, leaving Taiwan lacking in new sources of economic dynamism," Ho says.

"When the potential profit, risk and tax burden associated with speculating in real estate and stocks are far more advantageous than investing in new businesses or research and development, why would business owners and rentiers bother investing in industrial upgrading? Why would they invest in the younger generation?" Ho wonders.

In the 1970s, Taiwan generated one of the highest levels of national income in Asia, yet had the most equitable income distribution of any country in the region, a phenomenon described by the international community as the "Taiwan miracle."

That "Taiwan miracle" has a new definition today, however, representing the lowest economic growth of the four Asian Dragons (that also include Singapore, Hong Kong and South Korea) yet one of the most inequitable distributions of income in the world. This difficult plight serves as an unprecedented warning of the peril facing Taiwan's competitiveness and social stability.

Rather than hypnotizing itself behind official statistics, the government would be better off confronting Taiwan's income distribution problems, starting by reforming the property tax system and devising a comprehensive policy that also includes incentives for industrial innovation and upgrading and raising worker pay.

Such change is now more urgent than ever.

Translated from the Chinese by Luke Sabatier