Fighting for Taiwan: Chen Yu-chin

Above Any Label – A New Kind of Taiwanese

Source:CW

The daughter of a veteran soldier from China and an Indonesian-Chinese mother, Chen Yu-chin used her writing to define herself in a way that transcends established labels, paving the way for others in Taiwan with atypical family backgrounds to freely define themselves.

Views

Above Any Label – A New Kind of Taiwanese

By Pei-hua YuFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 600 )

The national flags of the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) above a giant elephant greet visitors from a wall on the first floor of the Brilliant Time bookstore in New Taipei City’s Nanshijiao area. Novelist Chen Yu-chin talks about her works in front of a small audience grouped around a sofa. She takes out her mobile phone and holds it facing the audience to broadcast the event live on Facebook. Then she begins to tell her story, which is a quest for identity against the backdrop of a bicultural family background.

The petite Chen has dyed her trademark short bob golden brown. The budding author with sparkling eyes ranks among the hottest new authors in Taiwan's literary scene. Chen, who has made writing her profession, is often invited to schools to talk about her project writing about “second-generation immigrants.”

When her debut novel Young Girl Kublai was published three years ago, Chen became the youngest author to be featured on the cover of the influential literature magazine INK Literary Monthly. Late last year, Chen published her second novel, Taipei People-to-be, which switches the focus from herself to her veteran soldier father, her Indonesian-Chinese mother and the many aspects of the immigrant experience in Taiwan.

Who Am I?

Chen’s father, who fled to Taiwan with the military after the Chinese civil war, hails from China’s Fujian Province. Her mother is an ethnic Hakka from Indonesia. In 1985, Chen’s mother bought a one-way flight to Taiwan to look for work. At the time, the money spent on the ticket would have bought her a house in Jakarta. Having arrived on a tourist visa, she knew that she needed to find a husband in Taiwan before her six-month visa expired. Eventually, she settled down in Taipei’s Sanchong District, placing her bet for a better life on a veteran soldier who was older than her own father.

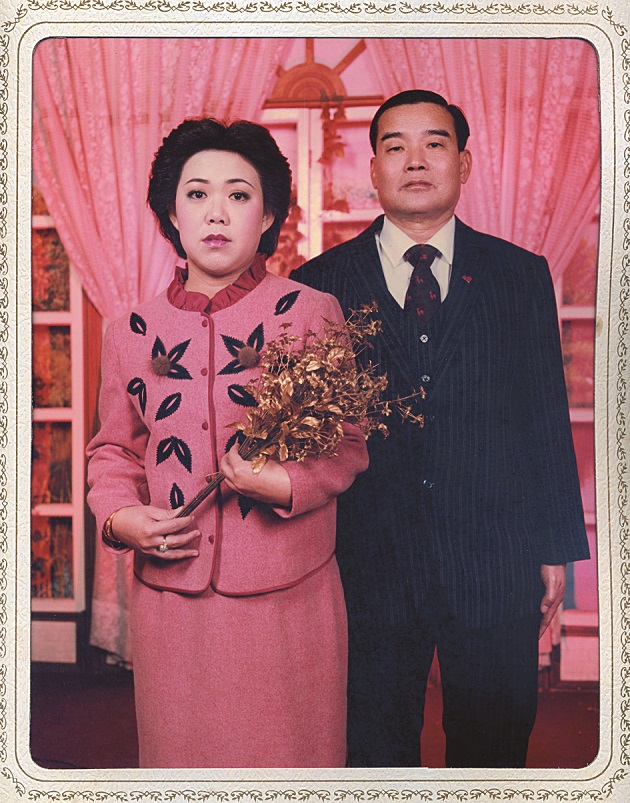

Chen’s Indonesian Chinese mother and her father, a veteran soldier from Fujian Province in China.

Chen’s Indonesian Chinese mother and her father, a veteran soldier from Fujian Province in China.

At the tender age of five, Chen, the only daughter, already knew that she had better not respond if someone asked her mother “Where are you from?” because her mother would always make up a different answer depending on the circumstances. If her counterpart did not understand the Hakka language, she would say she was Hakka. When talking to Hakka people, she would claim to be Cantonese, and when meeting Cantonese she would declare that she was Hakka.

When Chen was in fourth grade, her classmates would begin to ask whether her mother was a “foreign worker" or “foreign spouse.” Chen would always change the subject, partly because she did not really understand the meaning of these terms, and partly because she did not want to highlight that her mother was different from others.

Her mother’s reluctance to acknowledge her background reflects the disdain that Southeast Asian immigrants experienced in Taiwan at the time. Consequently, it is not surprising that Chen learned little about her Indonesian heritage during her childhood. Before Chen turned 20, she always regarded herself as a mainlander because of her father’s origin. She only began to describe herself as a child of an international marriage after graduating from university.

Chen was already in her early twenties when she heard the terms “new children of Taiwan” or “new immigrant” for the first time, at the same time feeling that she belonged to this group of people.

However, the second generation of immigrants that were often featured in Taiwanese media were usually either the offspring of underprivileged parents with low income or poor formal education, or successful “multilinguals with an annual income of more than NT$1 million.” Chen did not fit into either group, which made her think: “What about those people who are between the two extremes of this spectrum? I had better write about and express this awkward feeling that we people who feel like we don’t belong experience.”

Stories that Resonate

Therefore, Chen began to tell the people she met that she was planning to interview second-generation immigrants to document their stories. She would first tell them her own story and then ask whether they knew people with a similar background. Initially she wrote down these stories in a news reporting format. Subsequently she switched to a first-person narrative. Depending on how much the interviewee was willing to share, she was open to using the person’s real name or an alias in the interview, a practice harking back to the time when she evaded any clear statement with regard to her mother’s background.

During her initial quest to find similarities, Chen soon discovered that the stories were as different as the individuals who told them. Among the nearly 20 second-generation immigrants that Chen interviewed for her project were people who identified with their parents, while other felt alienated or were in the process of getting to know the native country of their father or mother. The immigrant parents hailed from many different places, including Indonesia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Shandong Province and Hainan Island in China.

Interestingly, not only second-generation immigrants were touched by the stories but also people who migrated from Taiwan’s rural areas such as Yunlin to cosmopolitan Taipei, because they had experienced a similar sense of uprooting and unfamiliarity with their new surroundings. Chen observes that "migration" is the common denominator that resonates with immigrants from abroad and domestic migrants alike.

Brilliant Time bookstore founder Chang Cheng believes that, as a graduate of the Graduate Institute of Drama and Theater at National Taiwan University, Chen has strong writing skills. He sees her interview project as a very good example because it encourages second-generation immigrants to stand up for themselves.

When Chen shared her story at the Brilliant Time bookstore in April, a young man in the audience felt inspired by her work. Previously, he had never felt that he was special in any way. However, after hearing about Chen’s search for her own cultural identity, he had the idea that his mother’s family history was probably worth writing down, and he could use the book project as an opportunity to reconnect with his Vietnamese-Chinese maternal relatives living in Australia, Canada and the United States.

As a second-generation immigrant author, Chen reminded the audience that “there are many different kinds of second-generation immigrants; I am only one of them." Chen pointed out that the term “second-generation immigrant” and the concept behind it will likely be short-lived. But presently it subsumes all those whom mainstream society overlooks, ensuring that they are seen.

Chen’s ultimate goal is to use these stories to let everyone discover the many different faces of Taiwanese society, until one day it won’t be necessary anymore to use the term “new immigrant” and other words to make a distinction between different groups. Then everyone will be able to choose the cultural identity they feel most comfortable with and not have to hide their real self; they could be Pingdong people, Vietnamese, mixed Filipino-Taiwanese, Japanese culture lovers, or even aliens.

Translated from the Chinese by Susanne Ganz