Table Tennis Star Chuang Chih-yuan

Eyeing One Last Olympic Games

Source:CW

Taiwanese table tennis veteran Chuang Chih-yuan is still going strong at age 34, rare for an Asian player. Still full of competitive juices, Chuang is preparing for one last shot at an Olympic medal in August.

Views

Eyeing One Last Olympic Games

By Elaine HuangCommonWealth Magazine

Just after 9:30 p.m. on the night of Jan. 18, Taiwanese table tennis player Chuang Chih-yuan arrives at Taoyuan International Airport toting his own luggage as he prepares to fly to Hungary.

His name has become synonymous with Taiwanese table tennis. In 2003 at the age of 22, Chuang vaulted past the now-retired Chiang Peng-lung in the men’s singles world rankings and has remained Taiwan’s top-ranked player since then, rewriting the country’s table tennis history.

The 1.69-meter Chuang is dressed in black and sports short hair and a well-groomed mustache as he prepares to head to Europe. He doesn’t smile much, his resolute demeanor imbued with an indescribable solemnity, and his big eyes appear calm and decisive.

Waiting for him in Hungary is the first tournament of the year on the ITTF (International Table Tennis Federation) Tour, to be followed by an event in Berlin the following week.

His busy schedule on tour keeps Chuang on the road for more than half the year, and it would once again keep him from being at home for Lunar New Year festivities in early February. When asked when he was last in Taiwan to celebrate the occasion with his family, Chuang can’t remember.

“I wasn’t here last year or the year before, but I’m used to it,” says Chuang as he watches his check-in luggage go through the inspection checkpoint.

A week later, word comes that Chuang, who was top-seeded in Hungary, won both the men’s singles and men’s doubles titles there, and he would go on to reach the semifinals in the singles in Berlin.

For Chuang, who turns 35 in April, 2016 carries special significance. The Summer Olympics will be held in Rio de Janeiro in August, presenting Chuang with his last opportunity for an elusive Olympic medal. His previous trip four years ago in London ended in a match that left Taiwanese fans distraught and heartbroken.

A Heartbreaking Scene, Frozen in Time

Seeded fifth in men’s singles at the London games, Chuang seemed to get a break when Adrian Crisan of Romania knocked out fourth seed Timo Boll of Germany in the fourth round, opening an easier path to a medal.

The Taiwanese veteran promptly dismissed Crisan in four straight games in the quarterfinals, and though he lost in the semifinals to second seed Wang Hao of China, he had a chance to take bronze with a victory over eighth seed Dimitrij Ovtcharov of Germany.

A medal-starved Taiwanese fan base (Taiwanese athletes only won two medals in London) watched in agony as Chuang took the first five points of the opening game only to lose it 12-10, then reel off the next two games 11-9, 11-8 and hold two game points at 10-8 in the fourth for a commanding 3-1 advantage. But Ovtcharov stayed alive with a demoralizing topspin that barely caught the edge of the table, and then rattled off the next three points to even the match.

A demoralized Chuang was outclassed in the fifth game but recovered to gain three game points in the sixth game, only to lose them all, and when he sent a return long on match point for the German, Chuang’s medal dreams were shattered.

Despondent and upset, Chuang shed tears when out of view of others. He felt as though he had disappointed his country, his family and, most importantly, himself.

On the long trip home from London, he didn’t say a word and did not pick up a racket for two weeks after returning to Taiwan, the longest break he had ever taken from table tennis. His mother and coach at the Olympics Lee Kuei-mei was worried that her son, who is always eager to do well, would not recover.

“To this day, I’m still not able to watch the full recording of that match,” Chuang reveals nearly four years later. “When I watch it, the feeling of defeat returns.”

A warrior, however, is not afraid of any opponent, including facing his own defeated self.

Ranked sixth in the world in men’s singles in February, Chuang’s goal is to get one of the top four seedings in Rio to better position himself for a medal run.

“There are almost no Asians who are still playing at the top echelon of the sport at age 35 like he is. The top Chinese players of his generation all retired long ago,” says longtime table tennis observer and Liberty Times sports center director Hsu Ming-li, suggesting that winning a medal will be even more challenging for Chuang this year.

Having evolved from his days as a teenage table tennis wiz with dyed blond hair into a mature 30-something battle-tested veteran, Chuang is still fighting but also determined not to put too much pressure on himself.

“I don’t overthink things. All I think about is how to get better,” he says.

Leaving Home to Train in China, Germany

It is early January at the Chih-yuan Ping-Pong Stadium – a multi-story table tennis training center in Gushan District in Kaohsiung. The pitter-patter of balls being hit in rhythm accompanied by low grunts are already emanating from the center’s fourth-floor training area at 9:30 in the morning as Chuang works on his game. He trains every morning and afternoon and runs at night.

For more than 20 years, from when he first toyed with the idea of pursuing a career in the sport, Chuang has always pushed himself, refusing to ever get complacent despite the grind.

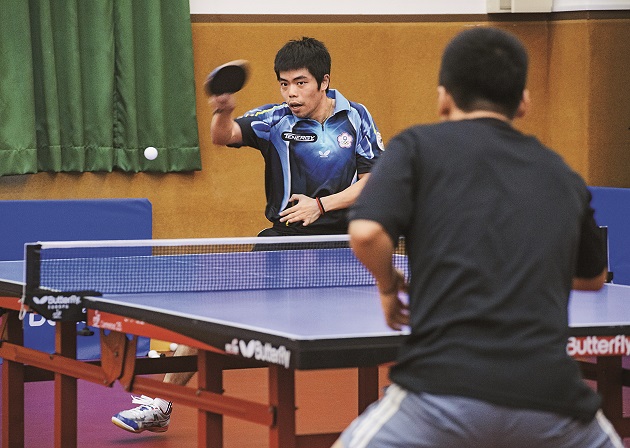

Chuang Chih-yuan's life is centered arounf table tennis venues. He spends more than half the year competing around the world.

Chuang Chih-yuan's life is centered arounf table tennis venues. He spends more than half the year competing around the world.

His arms and legs seem to be of unusually fair complexion for an athlete because table tennis arenas have always been his training grounds and battlefields. While others were indulging their youthful pleasures, Chuang was honing his craft day after day in fluorescent-lit gyms. He has been a lonely warrior, carrying his own bags and rackets on never-ending expeditions through Asia and Europe, learning to deal with losing on his own while making his way onto the international stage.

“Chuang Chih-yuan and Chiang Peng-lung both have been ranked as high as third in the world. In terms of pure talent, the smaller Chuang may not be as gifted as Chiang was. But he has a natural talent for practicing, able to hold up when others can’t. This is one of the main reasons he’s been able to continue on until today,” Hsu says.

Anybody in Taiwan who decides to become a table tennis professional is destined for a life of solitary training, and Chuang has been no exception.

Chuang’s mother, once a professional table tennis player herself, realized that Taiwan’s table tennis resources were limited. Once her son decided to dedicate himself to the sport, she sent him to train in China. She borrowed money to finance the overseas gambit and asked everywhere for help.

Chuang went to China to train on a long-term basis when he was in the eighth grade. Having left his mother’s side for the first time in his life, Chuang couldn’t help but weep over the lonely feeling of homesickness while sleeping in the living room of his Chinese coach’s home.

Chuang later joined the Hubei Province team to train, and his mother bought a house in the provincial capital of Wuhan to help settle him in his new environment. But the apartment was rather crude and lacked any form of insulation – getting so hot in the summer that it was hard to sleep and so cold in the winter that it fueled fears of frostbite.

Chuang got up every day at 6 a.m. and did some basic exercises, and was practicing by 7:30 a.m. He spent more than 10 hours a day in morning, afternoon and night training sessions, and during his spare time he studied Chinese, English and math.

“He and mom really endured hardship. I was at their side so I know how it was,” says Chuang’s older brother Chuang Chih-hsiung. From elementary school to high school, the brothers slept on the same bed, giving Chih-hsiung a front seat to his younger brother’s tribulations.

But Chuang Chih-yuan never complained and in fact was more dedicated than other children. He understood that living in China was a big expense for his mother and that his family was there because of him. So while other children could take time to play, he could not. He devoted himself to his training, and when practice ended, he grabbed seniors to continue playing, to the point where people were afraid to run into him.

In his first year of high school, he began training with China’s second national team. There, Chuang had the chance to train with future Chinese stars, including 2008 Olympic gold medalist Ma Lin and 2004, 2008 and 2012 Olympic silver medalist Wang Hao, and it was then that he made great strides forward.

At the 1999 World Table Tennis Championships not long after Chuang turned 18, he began making his mark after defeating some better known players, including 1988 Olympic gold medalist Yoo Nam-kyu of South Korea.

“He is a real grinder. We have paid attention to him since he was young,” said Liu Guoliang, considered one of the greatest players of all time who retired in 2001 and is now the head coach of China’s national table tennis team, in a previous media interview.

Realizing Chuang’s abilities, China no longer allowed him to train with its national team. So Chuang set off to Germany, where he would live for six years and train with one of Germany’s leading table tennis clubs, Ochsenhausen.

But it took some getting used to. The game was played much differently in Europe than in Asia. The smaller Chuang crowded the table and played a quick, attacking style while Europeans preferred a slower rhythm standing away from the table.

Initially, Chuang and his playing partners rarely had rallies lasting more than two shots, and nobody wanted to practice with him. His only option was to train with the table tennis serving machine and compete in as many events as possible around Europe to gain experience.

Having spent time in both China and Germany, Chuang skillfully meshed the Asian and European playing styles, and his career took off in 2002. He reached the finals of the Qatar Open after defeating then World No. 2 Ma Lin of China in the semifinals, and also made the finals of the Japan Open and Dutch Open before breaking through with a victory in the season-ending Pro Tour Grand Finals in December.

The next year, Chuang rose to third in the world, and, along with Boll of Germany and Wang Hao of China, he was considered one of the new stars of world table tennis.

Hitting a Low in his Peak Years

Perhaps affected by his own excessively lofty expectations or those of others, Chuang was unable to sustain his success.

Seeded fifth in the men’s singles at the 2004 Olympics in Athens, he was eliminated in the quarterfinals by fourth seed and eventual silver medalist Wang Hao.

Four years later in Beijing where Chuang was seeded seventh, he was ingloriously ousted in the round of 32 in seven games after holding a 3-2 lead by unseeded Yang Zi, a China-born player representing Singapore who was never ranked higher than 21st. Chuang felt he played tight, unable to rediscover the looseness he once had.

In what are normally the peak years for table tennis players – their mid-20s – Chuang struggled, often allowing lower-ranked players to come from behind in matches and beat him. In the six years following his ascension to the world No. 3 ranking in 2003, his results were lackluster, and he fell out of the world top 10.

“When you fall, it happens a lot faster than when you rise up,” says Chuang in a low voice of this down period in his career. “Without even realizing it, you lose it bit by bit until one day you have suddenly fallen.”

Many outsiders were concerned that he had completely lost his confidence.

But table tennis was everything to Chuang, and he would not easily give it up. Like a headstrong bull, he refused to leave the scene, deciding not to accept his many comeback defeats by lesser players.

“The problem was me. At that time, I was relying completely on my instincts rather than using my head. If I could go back to that period in time, I would talk to myself and analyze what my strengths were and where I wasn’t good enough,” Chuang says, admitting he was hurt by his stubbornness.

Chuang didn’t just want to beat his opponents back then. He wanted to “conquer” them by identifying the player’s strength and then trying to defeat him using that same strength. He would even ignore his strong backhand in favor of his weaker forehand, often ending up like a cornered beast with no way out in his matches.

The six-year funk had a silver lining, however, grinding away Chuang’s impulses and rough edges. He became less reckless and put more thought into each shot.

“It’s like playing chess. You try to figure out what your opponent’s thinking a step ahead,” Chuang says.

“He began to have tactical awareness, understanding that you had to use different tactics at different points in the match,” says the Liberty Times’ Hsu of Chuang’s maturation as a player.

When a more mature Chuang brought his fighting spirit to the London Olympics and advanced impressively into the semifinals (losing only two games in three matches), he was back in the spotlight after a long absence.

But that bronze medal match, with its cruel twists of fate and opportunities squandered, once again shattered his Olympic dreams and weighed heavily on him.

“I comforted him by telling that if winning a medal was meant to be, the gods would not have allowed that shot to happen,” says Chuang’s mother, referring to Ovtcharov’s pivotal shot that caressed the edge of the table in the bronze medal match and robbed Chuang of his momentum.

But is it really fate that has kept the Taiwanese veteran from an Olympic medal?

Chinese players have previously described Chuang as “not mean enough.” Unlike London gold medalist Zhang Jike, who plays with a swagger and rips off his shirt after victories, Chuang appears on court as a restrained, introverted well-mannered child who lacks the aura of a champion.

“I’ve never had a lot of confidence,” Chuang admits. “Maybe I still haven’t worked hard enough. If I had, I may have won that medal. Others may be practicing more than me and putting more into it at a deeper level. I don’t have the natural gifts others have, so I have to work harder,” he says humbly.

All athletes have their own special qualities and values. The athlete Chuang says he looks up to is professional baseball player Ichiro Suzuki.

“He’s professional and introverted. When he’s on the field, he doesn’t say much. If he doesn’t have a good game, he still follows his own pace,” says Chuang, analyzing Suzuki but seemingly describing himself. This is the real Chuang Chih-yuan – really into his sport but self-effacing.

Though getting over his setback in London was difficult, he eventually recovered. In 2013, he teamed up with fellow Taiwanese Chen Chien-an to win gold in the men’s doubles at the table tennis world championships in Paris, a first for a Taiwanese duo.

“He plays with a fighting spirit, he’s never willing to give up. I’ve learned a lot from him,” says the 24-year-old Chen, who reached the finals of the Hungary Open in January before losing to Chuang.

Perhaps aware of his own shortcomings, Chuang has taken whatever talent he has and developed it to the max, even if means bringing back bad memories.

“In the run-up to the Rio Olympics, I’ll watch the video (of the bronze medal match in London). I will still confront it,” Chuang asserts in a loud voice, as though making a promise to himself.

From Elite Athlete to Top Coach

Though his passion for playing continues to burn, Chuang has quietly kindled another fire.

To give her son a stable training place in Taiwan but also lay the groundwork for his desire to get into coaching, Lee Kuei-mei built the “Chih Yuan Ping-Pong Stadium” in Kaohsiung in 2008. Supporting the center, however, was a major source of pressure on Chuang, his winnings on tour going to repay the loans taken out to build the facility.

That pressure was eased considerably in late 2013 when Hon Hai Precision Industry Co. (known also as Foxconn) signed a 10-year sponsorship deal with Chuang and agreed to invest an additional NT$6 million in his table tennis center.

The center now draws young hopefuls from around Taiwan, who both revere and depend on the highly disciplined Chuang.

Having gone out into the world at a young age and relied on nobody but himself to survive in the fiercely competitive table tennis world, Chuang has always been independent and intolerant of being “soft.” But behind his hardened exterior, he has longed for the warmth of a team environment.

“When I was young, Mom opened a table tennis hall, and talking about it made everybody happy. I like that feeling. In building the table tennis center and teaching the game, that feeling returned,” says Chuang, offering a rare glimpse into his softer side.

Watching Chuang toting his luggage and gradually blending into the throngs of passengers at the airport, the imprint of past successes and failures indelibly etched in his psyche, it was clear that the 34-year-old has the energy to continue to grow, ready to take on pressure and to thrive once again.

Translated from the Chinese by Luke Sabatier

Chuang Chih-yuan Profile

Born: April 2, 1981

Education: National Taiwan Sport University, Graduate Institute of Athletics and Coaching Science

Currently: Professional table tennis player

Notable Results:

2003 Ranked 3rd in the world, the highest ranking ever for a Taiwanese player

2012 Men’s singles semifinalist at the London Olympics

2013 Men’s doubles gold medalist at the World Championships

2014 Men’s singles bronze medalist at the Asian Games

2015 Men’s singles bronze medalist at the Asian Championships

2016 Men’s singles winner of the Hungary Open