Intelligent Ironman Creativity Contest

A Life-changing 72 Hours

Source:CW

For 72 straight hours, teams of intrepid but isolated Taiwanese high school students battle through a real-life video game, forcing them to come up with creative solutions to problems. For many of them, it’s a life-changing experience.

Views

A Life-changing 72 Hours

By Rose SheuFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 586 )

Imagine this is a video game and you and your teammates are stuck in a space completely isolated from the rest of the world. You must complete your mission in three days to snatch ultimate victory.

As part of a group of 16- to 18-year-old teenagers, you will be without your parents to take care of you, your teachers to guide you or your smartphones to call on for help for 72 hours. Armed with only limited resources, you and your teammates must depend on only yourselves to solve problems together.

Unlike typical video games, however, this challenge does not take place in the virtual world. Known as the Intelligent Ironman Creativity Contest, it is a real game of adventure played by real people that was founded in 2004 for high school and vocational students.

The contest stems from a White Paper on Creative Education issued by the Ministry of Education in 2003. Originally planned to be held only once, it proved so popular that it has become a regular fixture that draws nearly 10,000 students a year. The 72-hour final is held in the summer, preceded by a grueling qualification process. Orientations for the 2016 event, to culminate in late July, have already begun, with registration and preliminary competitions to be held from December 2015 to early July 2016. International teams have been invited to participate since the contest’s third year.

Ko-fei Liu, a professor in National Taiwan University’s Department of Civil Engineering and the main mover behind the competition, describes the annual ritual as “a real paradise in which you can make your hero dreams come true.” Much more than simply a game of adventure, it represents inspiration for Taiwan’s existing education system, especially the nurturing of creativity.

When he first accepted the mission of designing the competition, Liu thought about how Taiwan’s schools all taught mere fragments of knowledge. Some focused on teaching students how to do something, without giving them any hands-on opportunities; others let their students get their hands dirty but did not teach why things were done in a certain way.

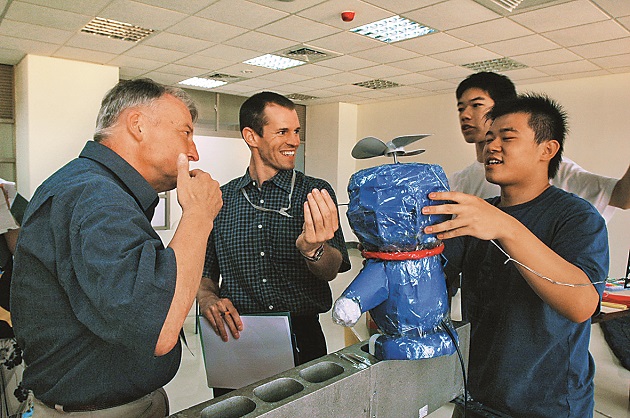

“The Intelligent Ironman Creativity Contest hopes to link these things together,” Liu says, drawing on his experience studying at MIT.

“Many courses at MIT don’t have tests. When course work is completed, the teacher gives you a project. If you are able to complete it to the teacher’s satisfaction, you can graduate. If you can’t get it done, then you don’t (graduate). That’s because MIT stresses the ability to solve problems in a very short period of time and even produce a finished product.”

Adventure Quests Co-exist with Real Tasks

Consequently, Liu and contest committee members decided that the spirit of the competition should focus on three elements: “wisdom” – using knowledge flexibly, stressing execution and making products; “endurance” – testing stamina, challenging limits; and “creativity” – solving problems, inspiring team creativity.

The introduction of international teams starting with the third annual contest has opened contestants’ eyes to even greater possibilities.

The introduction of international teams starting with the third annual contest has opened contestants’ eyes to even greater possibilities.

Liu, who has enjoyed playing musical instruments, bridge and video games since he was young, was very clear on the approach. To attract the interest of high school students, the contest could not rely solely on theories and ideas, Liu believed; it would have to be integrated with the video games they find so appealing. It was eventually divided into two parts – a main quest and side quests.

The main quest involves a test of creativity, with the organizers giving the teams an objective to achieve. In the sixth annual competition, for example, the main quest was to create “a present to give to the 22nd century.”

Teams had to complete the challenge within a set of parameters. The gift had to be presented on a 3-minute video, the video had to be put in a box that could be found by people after being preserved for 100 years, and the video could be played in the next century.

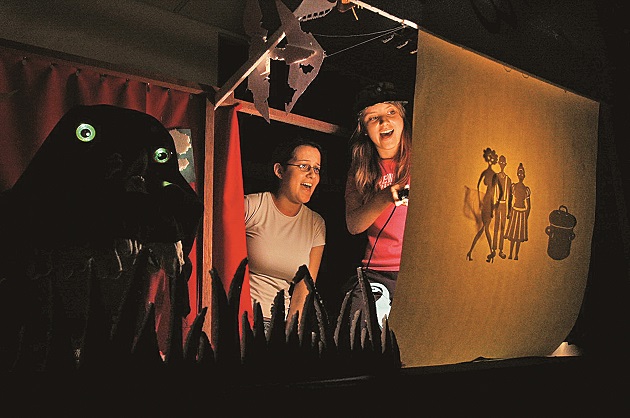

The side quests are similar to overcoming monsters or other checkpoints in video games. Experience points are accumulated and virtual currency earned every time an obstacle is cleared or a quest completed. The virtual currency can then be used to place orders to a virtual store online to gather the resources needed to complete the main quest. The side quests cover a wide range of fields, from nature and arts and culture to sports. Participating teams must be prepared to tackle all kinds of problems.

No Standard Answers, More Inspiration

One of those who participated in the competition, Tseng Pei-chi, was drawn to it by an alluring poster featuring a fortress and a clear sky while in her first year at Tainan Girls’ Senior High School. When Tseng saw the promotional poster, she decided to assemble a six-person team to participate in the Ironman challenge.

Now in her sixth year studying medicine at National Taiwan University, Tseng recalls her deepest impression of the competition.

Participants need to understand how to “drill holes” and challenge established rules, and come up with creative solutions to questions that have no standard answers.

Participants need to understand how to “drill holes” and challenge established rules, and come up with creative solutions to questions that have no standard answers.

“Professor Liu always stressed that there were no wrong approaches to the topics, to just go ahead and try. So every time we got a topic, we first looked for an opening and then drilled our way out through that hole,” Tseng says, using the “hole-drilling” analogy to describe the team’s effort to find innovative solutions to problems.

Fang Cheng-yi, who is now pursuing a doctorate in materials engineering at the University of California, San Diego, is another former participant who competed in the second annual Ironman event.

“Anything went unless it was specifically prohibited,” Fang recalls in describing the spirit of the event, which encourages contestants to challenge the organizers’ rules and shatter the idea that the organizers or people in higher positions have all the right answers. That, to Fang, was a major inspiration.

On Your Own for 72 Hours

When many Taiwanese students participate in competitions, they are generally guided and even prodded by their teachers and parents. But the emphasis in this competition is to force the students to rely completely on themselves. They are fully isolated from the outside world for 72 straight hours, and not only are their stamina and mental strength tested but also their teamwork, cohesion, strategy and tactics.

The major challenge to the teenagers is forging a winning team. Tseng recalls in putting her team together that she wanted it to have people with different skills and expertise to cope with topics ranging from science and the humanities to sports. So the team ended up recruiting two boys with strong math skills from Tainan First Senior High School.

Fang realized after competing years ago that his team lacked people who were strong in visual aesthetics and the ability to express themselves, putting them at a big disadvantage.

Aside from assembling team members who complement each other, even more important is how the team divides up tasks in working together to pursue a common objective. It takes good communication skills, learning to get along with different personalities and forging consensus amid severe constraints to harness the team’s greatest possible potential.

“We spent the first 24 hours of the 72-hour period arguing, but we were all very honest and stuck to the facts rather than getting personal. We eventually reached a complete consensus and decided how to approach the main quest,” Tseng recalls, describing the team’s communication model as often fiery but in the end effective.

How to best use the 72 hours is a major test of a team’s strategy.

Tseng and her teammates used the first 24 hours to brainstorm the main task, which was a key to their eventual victory. In the next 24 hours, the team went through a trial and error phase, and then it charged to the finish in the final 24 hours.

After enduring the 72-hour test, many participants emerged with a new perspective on life.

Fang felt the competition left him with a deeper appreciation of the importance of “self-learning.”

Tseng, who has returned several times to serve as a competition volunteer, also saw it as a life-changing experience.

“It made me believe in the possibilities of teamwork and made me more willing to accept people who were very different from me,” she says.

Tseng once again attended the competition as a volunteer this past summer, and it picked her up at a time when she was emotionally down because of setbacks in her research.

“When I saw these high school students, it gave me a little bit of a mental boost. It seemed like I rediscovered my high school self who once had this much creativity and was this diligent and passionate,” she says.

Even nearly a decade after competing in this Ironman competition, Tseng remains deeply moved by the life-changing experience, just as many others who steeled themselves during the 72-hour odyssey.

Translated from the Chinese by Luke Sabatier