Asia’s Last Economic Virgin

Myanmar: Gambling on Tomorrow

Source:CW

Five years ago when Myanmar opened its doors, optimism prevailed. Now, ahead of the country’s first real democratic elections, the mood has turned cautious. Seven professionals there look at where Myanmar has been and where it’s going.

Views

Myanmar: Gambling on Tomorrow

By Yi-shan Chen, Elaine HuangFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 583 )

A high-chassis off-road vehicle slowly nudges forward as it fights through a pool of red mud, the sounds of strain evident.

This is Thilawa, Myanmar’s first special economic zone. It is located less than an hour south of the country’s commercial center, Yangon, near where the Yangon River empties into the Andaman Sea.

The zone’s existing port and its proximity to Yangon has made it a favorite investment destination of the Japanese and a key benchmark of the return of international community to Myanmar.

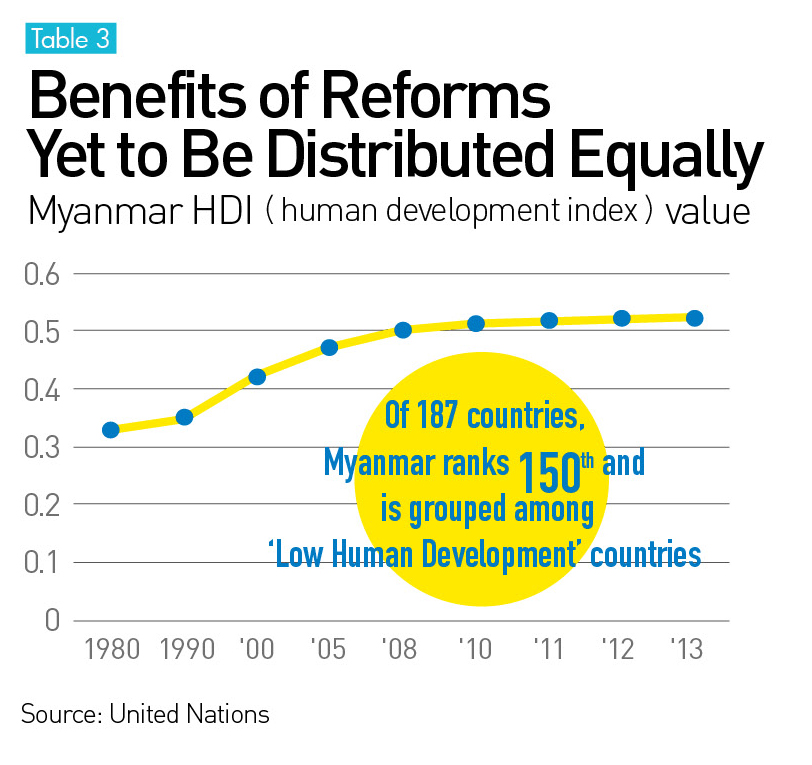

Myanmar’s human development index has made only limited progress, and the urban-rural divide remains huge.

Myanmar’s human development index has made only limited progress, and the urban-rural divide remains huge.

Myanmar represents the last big Asian market to open its doors and also happens to be the “hot” ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) destination among Taiwanese financial circles.

Over the past two years, Taiwan-based First Commercial Bank Co., E.Sun Commercial Bank Ltd., Cathay United Bank Co., Shin Kong Commercial Bank Co., CTBC Bank Co. and Mega International Commercial Bank Co. have all set up representative offices in the country.

Other Taiwanese companies have established presences in the Thilawa Special Economic Zone, and just this year, Pou Chen Corporation, the world’s biggest footwear manufacturer, made the biggest investment ever by a Taiwanese company in Myanmar when it poured US$100 million into a facility in Shwe Pyi Thar Township on the northwest outskirts of Yangon.

Always wary of pressure from the People’s Republic of China, meanwhile, Myanmar is now even considering allowing the Republic of China (Taiwan) to establish a representative office there.

Taiwan and others have seen the potential of the Southeast Asian country, but the impact of liberalization has been relatively uneven. Seven professionals inside Myanmar gave their perspectives on the changing face of the country to CommonWealth Magazine.

Economic Zone Executive Takashi Yanai

No Turning Back on Economic Liberalization

Economic zones stand out as microcosms of how economic powers have snared Myanmar, and they also mirror the relative strength of those competing interests.

Kyaukpyu District on the country’s west coast on the Bay of Bengal is the terminal point for Myanmar-China natural gas and oil pipeline joint ventures. Dawei, along the southern strip of land that borders Thailand, is home to a Myanmar-Thailand joint venture (that has recently added Japanese participation) – the planned Dawei Special Economic Zone.

Standing at the entrance of Myanmar’s first special economic zone, Myanmar-Japan Thilawa Development Ltd. president and CEO Takashi Yanai brims with confidence that the park will meet its targets for attracting investment.

Standing at the entrance of Myanmar’s first special economic zone, Myanmar-Japan Thilawa Development Ltd. president and CEO Takashi Yanai brims with confidence that the park will meet its targets for attracting investment.

But while progress in both of those zones is proceeding at a snail’s pace, the Thilawa development south of Yangon, run by a Myanmar-Japan joint venture Myanmar-Japan Thilawa Development Ltd., is advancing on schedule and getting companies to move in.

“This company, the first one in Thilawa, will go into production in October,” says the development firm’s president and CEO, Takashi Yanai, proudly, pointing at a big building behind a fence while driving along a smooth paved road in the zone.

Myanmar-Japan Thilawa Development has plenty of big hitters behind it. Myanmar and a semi-official Japanese organization, the Japan International Cooperation Agency, each have a 10 percent stake in the company, with the other 80 percent held by private companies in Myanmar and Japanese conglomerates Mitsubishi Corp., Marubeni Corp. and Sumitomo Corp.

The nearly completed zone has attracted 45 companies, of which about half are Japanese and four, including Century Iron and Steel Industrial Co. and the Toseva Group, are Taiwanese. Yanai feels that the land allocated to the first and second stages of the project will be sold out within three years.

Myanmar has had a poor track record of economic liberalization in the past, often backtracking after introducing reforms. Asked if he is worried that national elections set for November 8 could trigger instability and cause another U-turn, Yanai expresses confidence in the future.

When the country becomes democratic, he says, it will need economic development and foreign direct investment. Even if the opposition National League for Democracy takes power, “it will need foreign direct investment, too” Yanai adds.

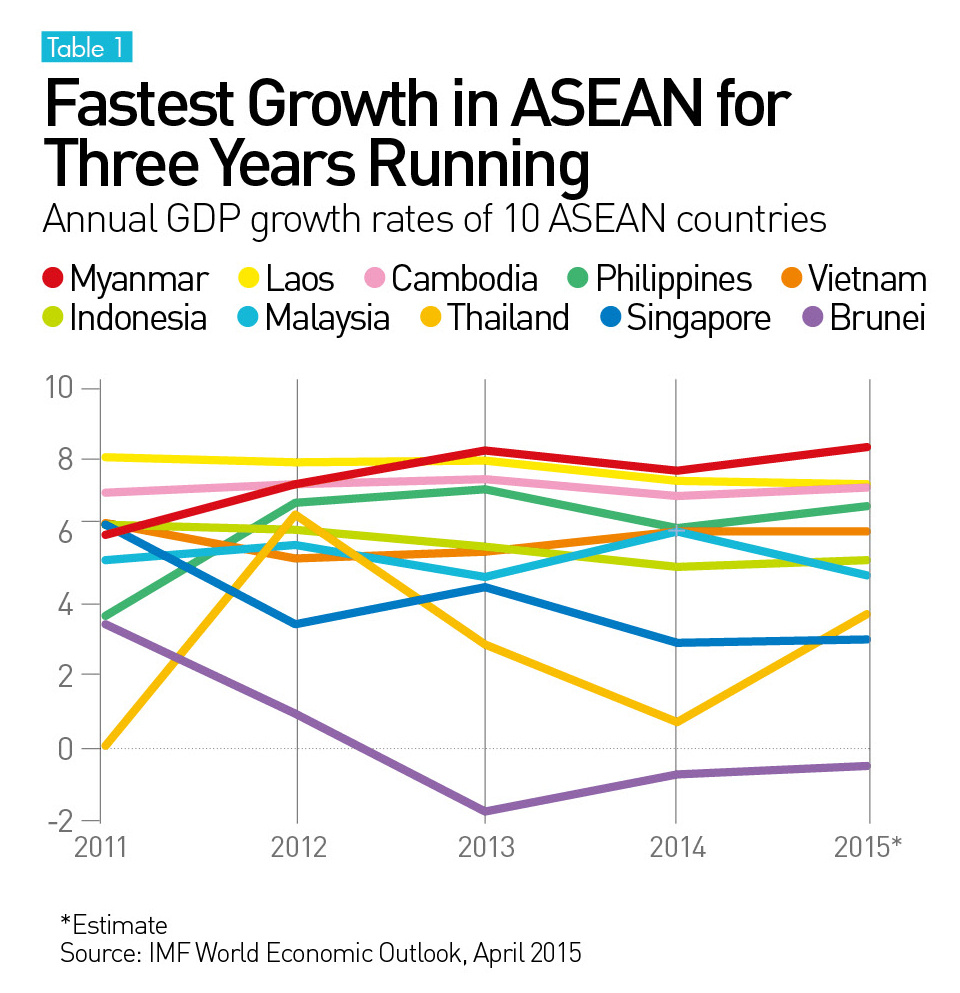

Almost everybody CommonWealth Magazine interviewed in Myanmar agreed with the Japanese executive: Myanmar, which has posted the fastest economic growth of any ASEAN country for three consecutive years (Table 1), has started on a path from which there is no turning back.

It may even emerge as a rare “newly opened country” to see a change in the political party holding power despite being the last country in ASEAN to open its doors to the outside world.

Media Executive Soe Myint

Myanmar’s People Ready to Grab Opportunities

Soe Myint lived in exile for 23 years in Thailand and India after being blacklisted for his participation in the ’88 Generation students group and expelled from the country. The group launched protests against the military regime in 1988 that spawned a nationwide pro-democracy movement.

In 1997, he and other journalists from Myanmar forced into exile founded a non-profit organization – online media Mizzima News. While still in exile, they set up a secret office in Yangon in 2006, quietly training staff there, and then began sending out news to Myanmar via satellite.

Soe Myint encouraged his colleagues and himself at the time to be as prepared as possible for the day Myanmar would become more open.

In 2011, when he finally stepped foot in his homeland after more than two decades in exile, Soe Myint felt “like a complete stranger,” he now admits. Determined to take the pulse of his country, he found most people did not initially have high hopes and were skeptical of the government. But after a year, with foreign investment starting to come in, expectations started to build and now people are rearing to go.

No longer a clandestine outfit, Mizzima News currently works out of an office in a commercial building, its rent financed by a loan from Yoma Bank, which is owned by one of Myanmar’s wealthiest individuals, Serge Pun. Other businessmen have invested in media interests as well, with the biggest shareholder of the English-language Myanmar Times also an entrepreneur.

Asked how he feels about Myanmar’s takeoff, Soe Myint, who is now the editor-in-chief of the multimedia news organization, admits to having mixed feelings. “That’s because I know there are still a lot of challenges. I’m excited, but I’m also worried.”

With less than a month before national elections, a sense of reality has descended on Yangon, as though the clock is about to strike twelve on the country’s Cinderella story.

Myanmar’s currency, the kyat, has depreciated 20 percent against the U.S. dollar this year and 50 percent over the past two years, and the room rates of five-star hotels that had risen five-fold in the recent past have fallen 30 percent recently. Flights to Yangon are only half full.

“The world is getting used to the fact that Myanmar is no Shangri-La,” Peter Maher, the head of Southeast Asian operations for Visa, told the New York Times as far back as June 2013.

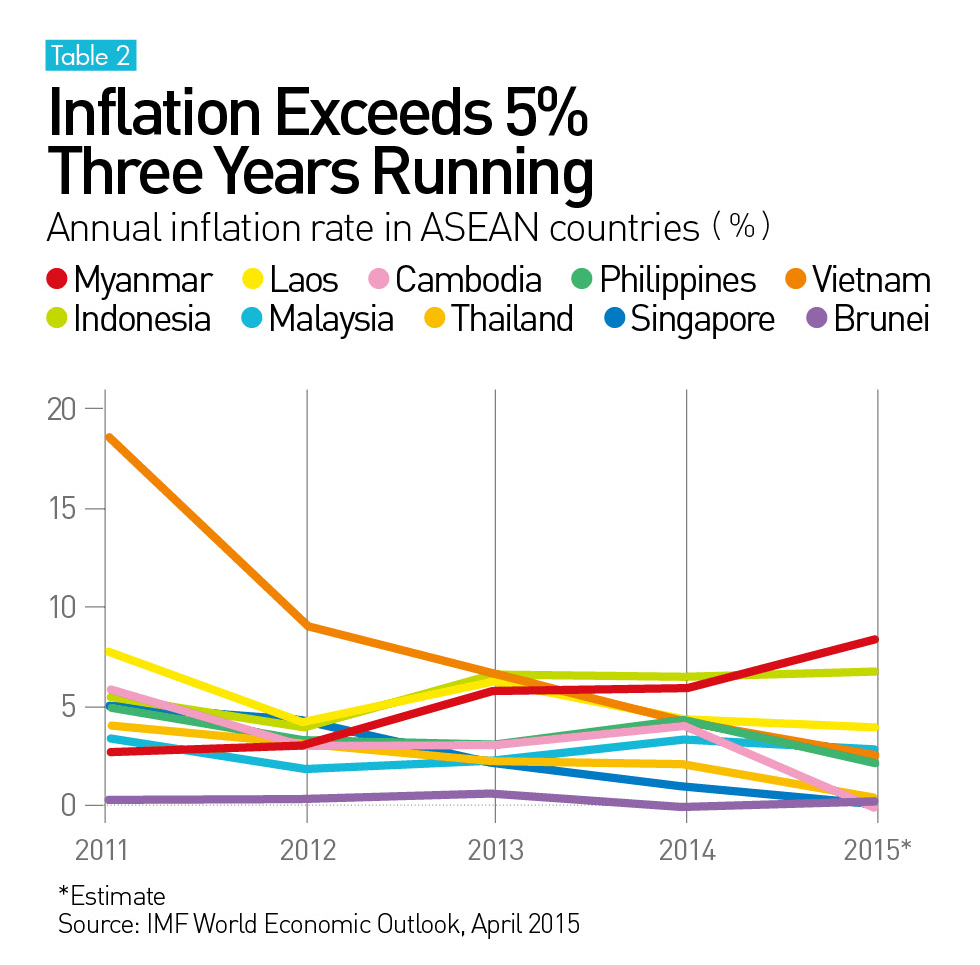

Unlike the first few years of Myanmar’s opening when speculative investment poured in, outsiders have applied a more pragmatic eye to the country in the past two years. Yanai says bluntly that even with tax incentives that are among the most attractive in the world, Myanmar and its poor basic infrastructure can still only draw investment from companies in labor-intensive sectors or those interested in Myanmar’s domestic market that are willing to make a long-term commitment there. (Table 2, Table 3)

Agriculture Executive U Kway Win

Opening a Zhongshan Rd. in Myanmar

Turn on to a small road at the 10-mile-mark of the Yangon-Mandalay freeway, and one quickly comes across some 40 transparent net houses cultivating agricultural produce.

This is Myanmar’s first net house cultivation project, managed by Sino-Myantai Eco-Technologies Co. Green vegetables from the net enclosures such as kale, Chinese spinach, mustard greens and bok choy are delivered every day at 4 in the morning to high-end Japanese-Korean supermarket ProMart, domestic supermarket chain City Mart and traditional markets in Yangon.

Myanmar lacks agricultural talent, but Sino-Myantai Eco-Technologies has brought a new look to high-end agriculture with net houses.

Myanmar lacks agricultural talent, but Sino-Myantai Eco-Technologies has brought a new look to high-end agriculture with net houses.

Myanmar’s lifeline, the mighty Irrawaddy River, once spawned a highly fertile alluvial plain that helped the country become the first rice exporter in Southeast Asia during the British colonial era. But today, Myanmar is facing the abandonment of rural villages, leading to a serious shortage of different types of food. Chicken, for example, is 30 percent more expensive than Europe.

The managing director of Sino-Myantai Eco-Technologies, U Kyaw Win, saw this agricultural bottleneck as an opportunity.

“The road we’re on now is Zhong Zheng Rd. That one is Zhongshan Rd.,” U Kway Win says as he walks the paths between the net houses, rattling off names of major streets common to most cities in Taiwan. He wants people to know that he is from Taiwan.

The 53-year-old executive grew up in Myanmar but went to Taiwan at the age of 18 to study. After graduating with a degree in forestry, he remained in Taiwan to work on bridge projects and ended up staying in the country for 32 years. Three years ago, as the oldest son in his family, he decided to return to Myanmar.

He noticed that in Yangon, a city of more than 7 million people, the only green vegetable one would see was water spinach. Other green vegetables and cabbage were also delivered to the city, but they weren’t fresh, prompting him to get involved in agriculture.

U Kway Win first went to agricultural hub Cingjing Farms in central Taiwan for 20 months to learn about growing crops and ended up insisting on importing seeds and seedlings from Taiwan and cultivating them in a net house. He also hired an agricultural expert from Taiwan.

Sino-Myantai Eco-Technologies’ strict quality control during the growing process has caught the eye of foreign supermarkets and Pizza Hut, which has just entered the Myanmar market.

U Kway Win now has five farms managed using different business models. In some cases, he contracts with local farmers to grow crops; in others he provides the technology to help others grow crops and collects a management fee.

“Agriculture is one of the core sectors nurtured by Myanmar’s government. In the next 10 years, this field will face a serious talent shortage,” says agricultural expert Chu Jun-hui, who was hired by U Kway Win from Taiwan.

Toseva Group Chairman T.S. Chou was commissioned this year to run an office building next to Yangon Port, creating a beachhead for Taiwanese-invested businesses in Myanmar.

Toseva Group Chairman T.S. Chou was commissioned this year to run an office building next to Yangon Port, creating a beachhead for Taiwanese-invested businesses in Myanmar.

Wood Business Executive T.S. Chou

Don’t Just Think Profit; Spread Good Will

Toseva Group Chairman T.S. Chou has been in business in Myanmar for 27 years and is called the “Myanmar King” by the banking community. He and his son, special assistant to Toseva Group J.X. Chou, are in as good a position as anybody to interpret the special culture of this Buddhist country.

Toseva is recognized as Taiwan’s biggest woodworking processing manufacturer. In its more than two decades in Myanmar, the company had only been involved in the trading business, but this year it invested in a processing plant in the Thilawa economic zone and was also commissioned to manage an office building at Yangon Port. It represents the biggest Taiwanese beachhead in Myanmar.

The somewhat portly 68-year-old Chou is hospitable and welcoming, typical of many adventurous first-generation Taiwanese entrepreneurs. To secure a steady source of wood, Chou set foot 27 years ago in Myanmar, one of the few places around the world with old-growth forest teak.

In Myanmar, business opportunities depend on personal contacts. Ask the father and son duo how to build a network of contacts in the country, and J.X. Chou will tell you: “In Myanmar, to do business, you first have to spread good will. You can’t just think about profits.”

“You have to give to receive” is a common belief in Myanmar, explaining why people donate generously after disasters or to their local temple.

T.S. Chou also stressed the importance of not making mistakes when building a network of contacts in Myanmar, because once a person is involved in a legally questionable business, decision makers with real power won’t risk dealing with that same person again.

Doing business legally is a necessity, he says, because only when you build up a good track record will the government and the business community be willing to trust and help you.

Advertising Executive Andy Annett

Myanmar Will Change at an Unbelievable Pace

What kind of ad strategy is most effective in Myanmar? Today Oglivy & Mather Myanmar Managing Director Andy Annett says many products are new to people in the country so advertising methods remain very traditional.

“Hold a cup, drink, then say it is delicious,” says Annett of the country’s advertising style as he acts out the part.

“The country is very unique. Don’t forget. They just opened up two or three years ago. Advertising, the Internet and mobile communication are all new for them,” adds Annett, who comes from England.

He asserts that Myanmar will change at an unbelievable pace. In the telecom sector, for example, Myanmar gave telecom licenses to Norwegian telecom operator Telenor and Qatar Telecom last year. The state-run Myanmar Post and Telecommunication then set up a 10-year partnership with NTT (Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation) and Sumitomo. As a result, the cost of SIM cards plummeted from US$2,000 to US$2, and the smartphone penetration rate immediately rose to 30 percent.

“Myanmar will change even more rapidly because of the Internet,” Annett says.

Bottle Material Executive Steven Lai

‘I Should Have Bought Twice as Much Land’

As a supplier of bottle materials to Coca-Cola in Myanmar, the Taiwan Hon Chuan Group has been ideally positioned to witness the growth in opportunities involving daily commodities there.

In 2007, Steven Lai, Hon Chuan’s managing director for Southeast Asia, was invited to Yangon by domestic beverage company Pinya Manufacturing Co. He learned that Myanmar’s non-alcoholic beverage market had the potential to grow 40 percent a year, and once the country opened its doors a few years later, Lai immediately went there looking for land.

In 2011, Hon Chuan laid down 35 years of rent to lease land in Mingaladon Industrial Park in the northernmost part of Yangon. Not long after, in 2013, Coca-Cola set up a joint venture with Pinya – Coca-Cola Pinya Beverages Myanmar Ltd. – to bottle the soft drink in Myanmar.

Walk into Hon Chuan’s complex and one quickly discovers that besides the two-story factory, most of it remains empty land.

Yet Lai says, “I now think I was too conservative at the time. I should have bought twice as much land,” because land prices have risen three-fold to four-fold since then.

“In Myanmar, if you’re not willing to gamble, there’s no tomorrow. You just have to be sure you can afford to lose,” says Chang Wei-Chi (張衛啟), the 47-year-old ethnic Chinese president of Myanmar beverage maker SamPar Oo Group. The conglomerate manufacturers not only plastic bottles and bottle caps but also purified drinking water and soft drinks and distributes its products around the country.

Chang, a native of Mandalay who attended university in Taiwan and studied foreign languages, comes from a family involved in the jewelry business. Ask him how much you have to be able to “afford to lose,” and he’ll tell you that you have to be willing to gamble 80 kyat for every 100 kyat you make. If you end up with only 20 kyat at the end, he says, you should accept your fate, be content, and don’t forget to make an offering of 10 kyat to a local temple.

That sense of adventure may be part of what is attracting people to Myanmar from around the globe.

Taiwanese lawyer Tseng Chin-po, who was sent to Myanmar by the Singapore-based law firm Kelvin Chia Partnership, talks about the many professional managers from all over the world he has met in Yangon. “These last few years, Yangon has not become more modern than Taipei, but it has become more international than Taipei,” he says.

Tseng has also witnessed the heavy influx of foreign investment and the return of Myanmar emigres and seen domestic companies boldly offer high salaries to hire foreign nationals. In July, Myanmar approved a five-year residence certificate for foreign professionals, and 200 were issued in the two months since the plan was launched.

Marketing Research Executive Moe Kyaw

Myanmar’s Malady: A Dearth of Talent

One of the returning emigres is Moe Kyaw, though he returned home in 1990. A graduate of the University of Westminster in England, Moe Kyaw is the managing director of Myanmar Marketing Research & Development Ltd., the joint venture partner in Myanmar of global marketing research firm Nielsen.

Now 50, Moe Kyaw is one Myanmar’s first generation of entrepreneurs who got their start back when the country had just abandoned communism.

He explains he decided to return home in 1990 because he felt that “Myanmar could (catch up to) Thailand if we changed our regime from communism.” Today, however, he is pessimistic.

Coca-Cola has invested heavily in Myanmar, and it hopes to establish a strong long-term presence by having its product sold in small shops around the country.

Coca-Cola has invested heavily in Myanmar, and it hopes to establish a strong long-term presence by having its product sold in small shops around the country.

“It will take at least two generations, 30 years, to (catch up to) Thailand,” says a pained Moe Kyaw, who sent his three children overseas to get their education.

Myanmar will need 30 years because the country’s education system has been destroyed, he says bluntly.

After 1988, when Myanmar’s military rulers suppressed the student protests, the junta moved all of the country’s urban universities to suburban areas to prevent students from stirring up trouble. It even arbitrarily closed universities or had schools not admit students, up until the reform-minded Thein Sein became president in 2011.

This educational wasteland lasted 24 years, more than twice as long as the ruinous Cultural Revolution in China.

“Burma was once renowned for its high literacy rates and educational standards, and the willful destruction of the education system is perhaps one of the most tragic things about the country,” wrote American journalist Emma Larkin (a pseudonym) in her 2005 book “Finding George Orwell in Burma.”

In 1990, after the military junta refused to recognize the results of an election for a constitutional committee won handily by the opposition, it began rooting out civil servants considered disloyal, including teachers, and systematically eradicated the “ability to think.” Though Myanmar claims to provide 10 years of free, compulsory education, students in Myanmar actually spend an average of only four years in school, according to United Nations figures.

Another challenge for the country is that while labor there may be relatively cheap, it may not be very efficient. One Chinese entrepreneur with business interests in Myanmar says that the same production line that needs 20-some workers in China needs 40-plus workers in Vietnam and about 75 workers in Myanmar. Myanmar’s minimum wage of 3,600 kyat, or about US$3, per day is about 40 percent lower than this year’s minimum wage of about US$5 per day in Vietnam, meaning that Myanmar labor may not be a great deal if the Chinese entrepreneur’s calculations are accurate.

Similarly, the country’s rigid bureaucracy can make life difficult for businesses to function. One example was the case of a vendor who made a mistake on a customs declaration, typing a “Z” in place of a “2,” and ended up being fined US$4,000 for the error. The authorities demand that the operations of vendors match their investment plans to the letter and are unforgiving of exceptions or contingencies, a vestige of the inflexible review methods of the past.

In her well-known speech “Freedom from Fear” 25 years ago, Aung San Suu Kyi said: “It is not easy for a people conditioned by fear under the iron rule of the principle that might is right to free themselves from the enervating miasma of fear.”

A quarter of a century later, that iron rule has weakened in Myanmar, but it remains difficult for the people of the country to free themselves from the legacy of the destruction of vitality and the ability to think engendered by the many years of fear.

Translated from the Chinese by Luke Sabatier