Mother of Taiwanese Literature—Chung Chao-cheng

'Longtan, My Home, In Dreams You Visit and Linger in My Soul'

Source:Chen Ka-wen

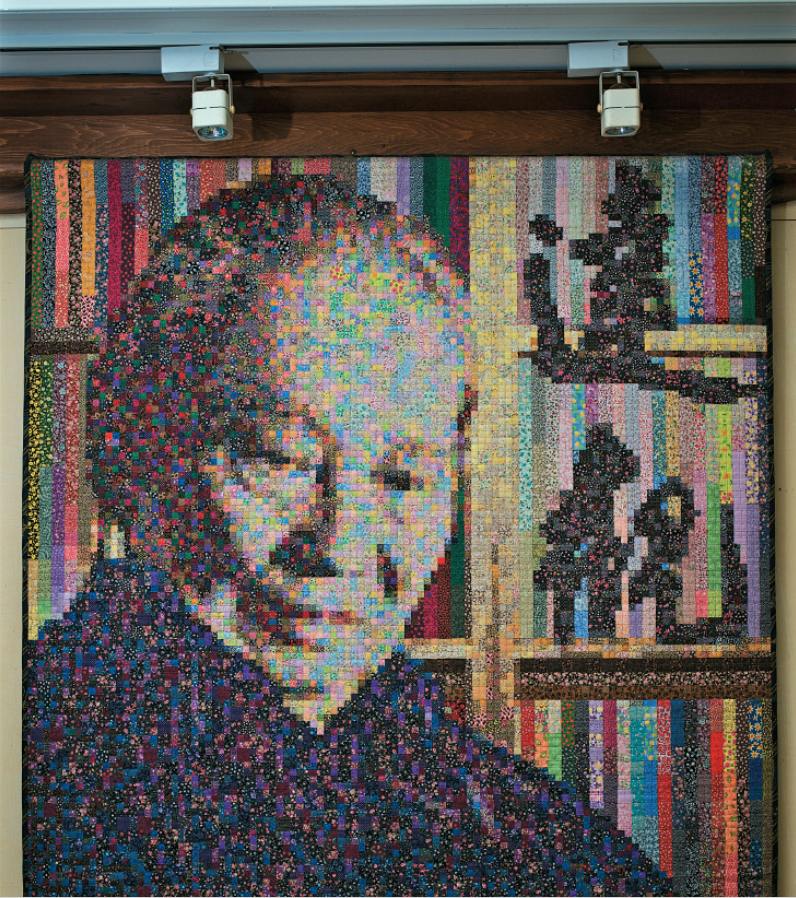

When 94-year-old Chung Chao-cheng walked into the living room, the visitors did their best to stay quiet as to cover up the exhilaration in their hearts. On this day, Chung would be talking about his home, Longtan—the land which never leaves his thought.

Views

'Longtan, My Home, In Dreams You Visit and Linger in My Soul'

By Jia Fan-yuSponsored Content

94-year-old Chung Chao-cheng walked slowly into the living room with his second son, Chung Yan-wei, supporting him alongside as the visitors – a dozen of them – all stood up. Everyone did their best to stay quiet as to cover up the exhilaration in their hearts. Silence pervaded until Chung Chao-cheng sat down, spread out his hands in a friendly way, and enunciated loudly and clearly: “Everyone. Please. Have. A. Seat!” Everyone laughed. On this day, Chung would be talking about his home, Longtan - the land which never leaves his thought.

Home Sweet Home

“Longtan is one of the regions that was developed relatively early in Taiwan.”

As he started talking, Chung went right back to the past during the agricultural era. In those days, droughts were a farmer's biggest fear. Fortunately, the large lake in Longtan made irrigation possible for local residents, also providing livestock water to drink and grass to eat. “Don’t underestimate the importance of grass. It is vital for farm animals.” Chung emphasized that Longtan residents were able to enjoy comfortable lives thanks to Longtan’s numerous water channels that transferred water into the region from all directions.

“Starting out in poverty during early cultivation stages, Longtan gradually became a small town with abundant produce. This is one of the things that Longtan people, including me, are the happiest about.”

Then, Chung jumped to another story – “According to legend, there was a year when the town encountered a serious drought; the water in the Longtan Lake was almost down to the bottom. Local residents urgently went to the side of the lake to pray to the Heavenly Grandfather. Surprisingly, rain started pouring down! This was when it began to storm. A yellow dragon even flew to the top of the temple.” Chung smiled and asked: “Do you believe in this legend?” Everyone smiled and looked at each other as Chung shook his head:

“I don't believe it, because droughts are Heaven's will.”

Despite being skeptical, Chung still talked about the legend with enjoyment. Deep in his heart, land is a mother figure. With a sincere and warm spirit of humanitarianism, he has described Taiwanese farmers’ daily lives in great detail. This led to the emergence of a “roman-fleuve” series based on Taiwanese history, and telling the story of families and the era they lived in. Examples of these include “Three Consecutive Stories of War Generations” and “Trilogy of the Taiwanese,” which were well-known roman-fleuves by Chung.

Chung's Teenage Years

“I’ve been a bookworm since my childhood!” In a loud and joyous voice, Chung recounted how his father opened up a grocery store in the neighborhood once he was too old to teach. Chung, who loved reading, took two or three nickels from his parents’ cashier counter. “Those were enough for me to subscribe to teen magazines for a month.” Chung said with a bashful chuckle:

“It doesn’t sound nice to say that I stole money. I just borrowed some for a while!”

Furthermore, the very first works that inspired him were the “Tan Hai" monthly magazines, sent across the ocean all the way from Japan.

The magazines were full of great folk stories. I had two or three friends at the time who shared the same interests as me. We subscribed to different magazines and would swap them with each other, so we had four or five to read a month. I read faster than everybody else and could finish a book in less than three days. I immersed myself in realities, fantasies, and random things every day. I enjoyed it so much that I never got tired of it...”

Chung closed his eyes slowly as a smile drew on his face. It looked as if, in his mind, he’d gone back to his wonderful teenage years of reading.

Other than reading, Chung also had an ear for music. “I’ve liked music since I was a child; I even taught myself to play the piano. I was born with absolute pitch.”The phonograph would only have to play a record three times: he would listen to it the first time; write down the notes as the music played for the second time; and slightly adjust and revise them the third time. Then, the entire melody was written down. “There would be absolutely no errors!” He laughed and said:

“I would have probably become a composer if I weren’t a writer!”

His voice revealed certain disappointment; when he was 20 years old, he suffered dysentery, which caused him to have high fever for a week, and the side effects of the medicines he took caused him severe hearing impairment. He has become almost completely deaf in recent years, but his ability to write music down into scores still remains. He couldn’t resist humming tunes happily on the spot as he talked. Chung’s world was still filled with music.

An author whose books can pile up to his height. A powerful and influential figure in the Taiwanese literary scene.

“What is Taiwanese literature to you?” Chung pondered for a while before he playfully answered: “I. Don’t. Know!” In fact, Chung spent all his life fighting for Taiwanese literature. This is absolutely manifested by his literary works.

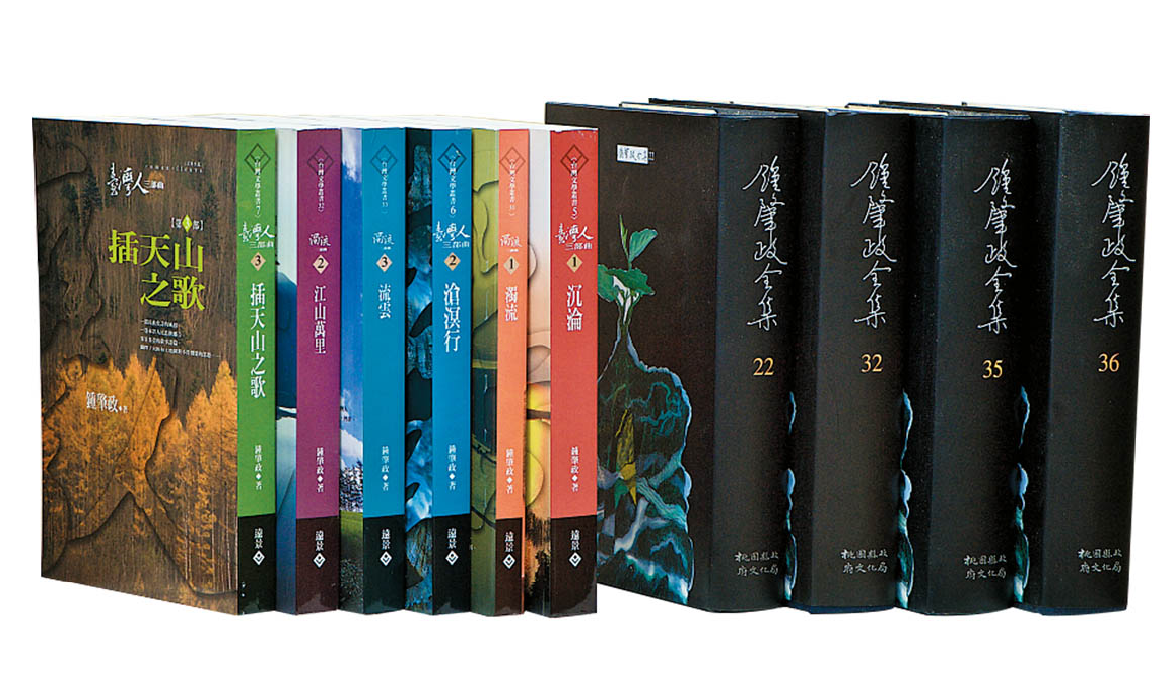

If all 38 volumes of “Complete Works of Chung Chao-cheng” were stacked up in a neat pile, it would turn out to be taller than Chung. Who'd say that the phrase “an author whose books can pile up to his height” was not an exaggerated description of Chung at all? Not to mention the large amount of translations of Japanese literature and literary compilations he had done.

“Among Taiwanese prolific writers, I am probably the most productive," he said with confidence.

Nevertheless, what places Chung Chao-cheng as an important figure for Taiwanese literature isn’t just his original works; he is an exemplary individual.

In 1957, he initiated a “social network” in which he connected literati from across Taiwan and encouraged everyone to take turns in reading each other’s works before writing down their thoughts and comments, then, sending them back to him. Afterwards, Chung would organize them and separately send them back to his literati friends as engraved steel plates or mimeograph letters. It was the post-war era and, during Taiwan’s White Terror period, everyone smelled danger in the air. Very few people were willing to think about others. However, Chung not only wrote himself, he also acted like a “literature agent” as he encouraged people to write and take great pains in doing it. He even submitted some of his literati friends' works for publication! He did these because he cherished a dream.

“Taiwanese literature should have a system of its own. We need to write about our own land using our own language!”

In Taiwan, Chung was the first national writer to have his work published on the newspaper supplement of United Daily News. Before this, the literary world was dominated by mainland writers. Since he received Japanese education, Chung only started learning Mandarin Chinese when he was 20 years old. Therefore, he had to translate from the Japanese in his head to Chinese. He started by making ten submissions and receiving ten rejections and then, slowly, made some progress, receiving nine rejections out of ten submissions.

At first he hesitated, thinking “am I a fool?” and “am I all alone in this world?” up until the tenth year of sharpening his abilities; he successfully published “The Dull-Ice Flower” – a work that made him an overnight sensation.

Following this, he joined the “Taiwan Literature and Arts” magazine established by Wu Zhuo-liu, as an editor. When he wasn’t writing, he exerted great efforts to cultivate writers of the next generation, including people like Chen Ying-zhen and Dong Fang-bai. He was also proactive bringing attention to the achievements of Taiwanese writers from previous generations. Towards the end of the 1970s, he successively prompted the establishment of the “Chung Li-ho Memorial Hall," “Yang Kui Memorial Hall,"“Wu Zhuo-liu Memorial Hall," and “Lai He Memorial Hall," among others, as he devoted himself to promoting Taiwanese literature. While he had written inscriptions for many memorial halls, he insisted on not writing the inscription for the “Chung Chao-cheng Literature and Lifestyle Cultural Center," which was soon to be established. This was because he was truly a zealous, selfless, generous, and humble elder.

Apart from his dedication to the promotion of Taiwanese literature, Chung also proactively participated in the promotion of Hakka movements.

When the “Taiwan Hakka Association for Public Affairs” was established in 1990, he came up with the slogan: “New Hakka," which was to encourage everyone to no longer identify only with glories of the past, but to bravely declare that “we are New Hakka. We are Hakka who grew up in Taiwan.”

The One Person Who Brought Success to the Entire Longtan District

Chung recollected memories from the 32 years he taught at the Longtan Elementary School; all his leisure time would go into writing. ” Holidays were the worst times for me because I had creative writing to do!” He laughed and said that creative writing was a task that required you to “rack your brain” and to “make something out of nothing.”

“The Dull Ice Flower” is the key to understanding Chung. The male teacher in the book reflects Chung’s own story. Instead of spelling out “Longtan” forthright as the name of the place in the book, other names were used as suggestive hints. Nevertheless, anyone who is familiar with Longtan would naturally find these amusing similarities as they read.

Social issues such as the gap between rich and poor as well as the rigid education system were presented through the innocent eyes of the male teacher in the book. In addition, through the painting prodigy’s life, we can encounter expressed criticism on society and humanity. These laid down a strong foundation for Chung’s future roman-fleuves.

To Chung, Longtan stands dearly as the place where he was born and grew up in. Cai Ji-min, who studied Chung’s works for many years, expressed:

“Rather than saying that Longtan made Chung successful, it should be said that Chung brought success to Longtan. By creating literature, Chung brought the entire society and culture of Longtan to the surface, enabling it to receive attention from everybody.”

The President of the Executive Yuan, William Lai, also commended highly the "Chung Chao-cheng Literature and Lifestyle Cultural Center,” of which the construction is almost complete. He expressed: “Chung was born in Longtan. He is a first-generation native Taiwanese writer from the post-war period. There are more than 20 million words contained within the works he created throughout his life. His works encompass the course of history from the late Qing dynasty, Japanese occupation, post-war era, up until democracy. They document Taiwanese people’s history of migration, the history of social development, and the struggles the Hakka faced through history. The government regards the "Chung Chao-cheng Literature and Lifestyle Cultural Center” as an important location. It incorporates and highlights Hakka literature as an element along the charming Provincial Highway 3.”

Give Chung’s works a read; make a visit to the "Chung Chao-cheng Literature and Lifestyle Cultural Center.” Feel the depth of Chung Chao-cheng’s literary talent, boundless thoughts, and his generous way of life. This would be a wonderful encounter to make in your life.

"Longtan is my home; it’s always in my dreams. Longtan, my home, in dreams you visit and linger in my soul."—Hakka Poetry by Chung Chao-cheng

Author: Jia Fan-yu

Photographer: Chen Ka-wen

This article is a repost from《Provincial Highway 3 - The First Hakka Village in Taoyuan》. Published by CommonWealth Magazine.

Edited by Frecilia Lee

Additional Reading

♦ The Hakka Cultural Renaissance Memories─Tea, Camphor Laurel, and Sugar Cane

♦ The Hakka Cultural Renaissance Memories Along a Mountain Route

♦ Bike Riding in Old Town Zhongli