'Banana Kingdom' No Longer

Taiwan's Farmers under Assault

Source:Domingo Chung

Taiwanese consumers have gotten into the habit of buying a banana at convenience stores, but that banana may ultimately stir up nightmares for Taiwan's farmers. CommonWealth Magazine takes you behind the scenes to explain why.

Views

Taiwan's Farmers under Assault

By Kuo-chen Lu, Yen-ling ChengFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 578 )

The fresh bananas stocked on the shelves of Taiwan's ubiquitous 7-Eleven convenience stores have spawned three phenomena you may not be aware of : About 100,000 bananas are sold every day that way; more bananas are sold through 7-Eleven annually than Taiwan exports; and the retail price of a single banana may be higher than the price of a kilogram of bananas at the farm level.

Yet while the NT$18 bananas sold at 7-Eleven are grown in Taiwan, they only turn into a specialty product that commands a high price after being purchased by multinational fruit company Dole Food Company, Inc. So what is going on? Why has Taiwan submissively conceded its brand image as a "banana kingdom" to others?

Why Good Bananas Went Bad

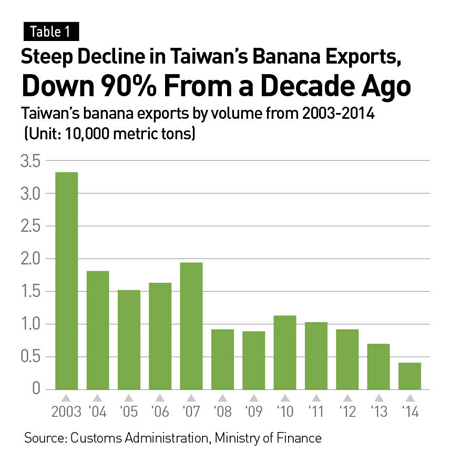

In 2014, Taiwan exported 4,000 metric tons of bananas, according to Custom's Administration statistics, and had only a 1 percent share of Japan's banana market, a far cry from the fruit's heyday in 1967 when Taiwan exported nearly 400,000 metric tons of bananas and had an 82 percent share of Japan's market.

The Taiwan Banana Research Institute, located in Jiouru Township in Pingtung County, is a symbol of the industry's better days. As the only research institute in the world solely dedicated to studying bananas, it represents the prosperity and world stature that Taiwan's banana sector once possessed.

On July 1, as dawn lights up Pingtung County's banana fields, the institute's banana collection and processing center bubbles with the return of human voices that have not been heard for some time. Trucks delivering clusters of recently harvested bananas shuttle in and out, dropping off the fruit for processing. The clusters are then cleaned automatically by machine and split apart, dried and sorted into different grades before being packed into cartons by experienced female workers. It is the year's first batch of bananas to be exported to China.

Leading the charge is banana industry veteran Lin Te-sheng, the chief secretary of the Taiwan Banana Research Institute. In an earlier job at the Taiwan Provincial Fruit Marketing Cooperative, he developed such a keen eye for bananas that he can determine in a flash which ones are good enough for export and which ones fail to make the cut.

Keeping an eye on the quality of the bananas as they are processed, Lin offers a grim assessment of exports this year. After shipping 4,000 metric tons of bananas abroad last year, Taiwan had only sent 2,000 metric tons overseas in 2015 by the beginning of July and will have trouble hitting the 3,000 metric ton mark for the year as a whole, he says. In other words, the country once known as the banana kingdom, will export fewer bananas than the more than 4,000 metric tons of bananas 7-Eleven sells in a year.

Lin's voice carries a hint of nostalgia for the days when the fruit marketing cooperative forged a banana kingdom. At the industry's height, there was a pier at the port of Kaohsiung that handled only bananas, which were then shipped to Japan in dedicated cargo ships.

An integrated export system was in place that deftly coordinated exports and cultivation, ensuring that supply remained in balance with demand. Even if the market suffered a sudden plunge in prices or was hit by a natural disaster, a stabilization fund was in place to protect farmers' interests.

"The complementary measures at the time were very good," Lin recalls.

So why have banana exports fallen off so dramatically?

The Fall of an Empire

Lin says the biggest turning point came in 2005, even if there were already signs of decline before then. Banana exports that ranged between 37,379 and 55,433 metric tons a year between 1994 and 2000 averaged only 27,854 metric tons from 2001 to 2003 and plunged further to 18,141 metric tons in 2004.

Taiwan was once known as the “Banana Kingdom,” but Dole and 7-Eleven have created a new business model with sales of individual bananas.

Taiwan was once known as the “Banana Kingdom,” but Dole and 7-Eleven have created a new business model with sales of individual bananas.

In 2005, the government quashed the system that had been in place for decades by ending the fruit marketing cooperative's monopoly of Taiwan's banana exports and opening the market to competition. About a dozen trading companies jumped into the fray, signing contracts with farmers to grow large volumes of bananas with an eye toward the Japanese market.

Blind liberalization without any complementary measures or consideration for the overall market was one of the major factors in the decline of the banana empire. After the program was put in place, exports barely held steady for a few years and then plummeted. (Table 1)The trading companies contracted farmers to grow such large volumes of bananas that quality suffered and failed to meet export standards. Unable to sell the bananas abroad, the traders dumped their surplus on the domestic market with predictable results. The price for Taiwanese bananas dropped precipitously, most notably in 2006, 2007, 2010 and 2011.

Government's response to this market disruption constituted the second major blow to the banana kingdom.

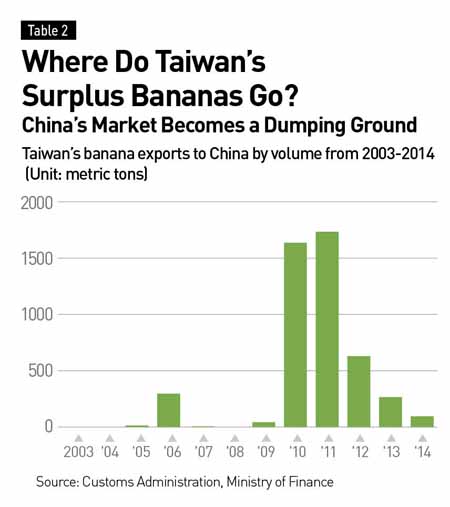

Whenever a surplus of any crop has materialized in Taiwan over the past 10 years, the country has turned to China and asked it to place "political" orders – in essence asking China to show "good will" toward Taiwan and accept agricultural products Taiwan is unable to consume.

This ill-advised practice has been used consistently since 2005, including when banana supplies have far outpaced demand. (Table 2)

Lu Cheng-chang, the former chief of the Yunlin County Agriculture Department and now the CEO of trading company Golden Field (Cayman Islands) Holding Corp., says selling the bananas to China through politically driven channels has backfired.

"The result has been that Taiwan has cut its own throat because it is exporting bad bananas to the Chinese. As soon as buyers open the container and discover that the bananas have gone bad, they become furious with Taiwan," Lu explains, lamenting that this kind of transaction has destroyed the reputation of Taiwanese bananas.

Taiwanese bananas, which once fetched the highest price of any banana sold in Japan, ended up being sold in China for less than Philippine bananas, which have an 80 percent share of the Chinese market and go for about four to six renminbi a kilo. In 2011, Taiwanese bananas sold for half the price of the Philippine products.

This approach of selling lower-grade fruit to China represented a stunning lack of awareness of how to manage the Chinese market over the long term and has hurt Taiwan immeasurably.

Dole: Good Quality, Steady Supply

Another major factor in Taiwan's decline was its unwillingness to change with the market as a formidable adversary – Dole – was rising up in the Philippines.

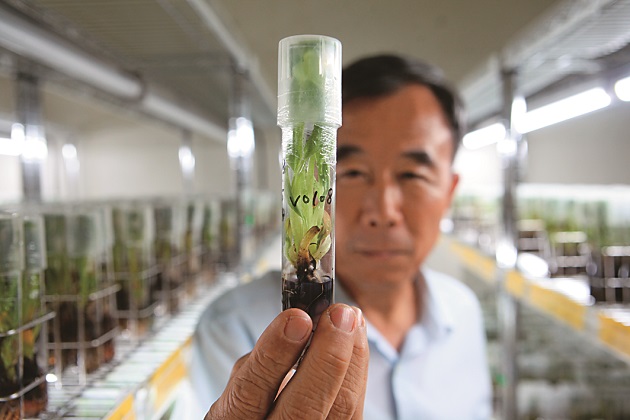

Taiwan Banana Research Institute Director Chao Chih-ping holds the seedling of a new banana variety. The institute, the only one of its kind in the world, is testament to the fact that Taiwan was once a “banana kingdom.”

Taiwan Banana Research Institute Director Chao Chih-ping holds the seedling of a new banana variety. The institute, the only one of its kind in the world, is testament to the fact that Taiwan was once a “banana kingdom.”

Taiwan Banana Research Institute Director Chao Chih-ping says that when Japan began asking supplier to ship small packages of cut bananas to reflect changing consumer habits, Taiwan missed the boat. Lacking the awareness needed to make adjustments to their business models, Taiwanese traders rejected their Japanese clients' requests, unwilling to cater to the new trend among Japanese consumers to buy just a few bananas at a time rather than a whole cluster.

One company did answer the call, however – Dole (which sold its Asia fresh produce business to Itochu Corp. in 2012 but still uses its brand name). It grew bananas in the Philippines to satisfy the needs of Japanese customers and even sponsored the Tokyo marathon to promote its bananas.

Undermined by a civil war among domestic trading companies and by farmers and businesses unwilling to adapt to a changing market or build a solid foundation in the Chinese market, Taiwan ceded its position as the banana kingdom to Dole, which has become the dominant banana supplier in Asia.

Because of Dole's prominence in the market, the Philippines now export about a million metric tons of bananas to Japan every year, about 250 times the volume shipped by Taiwan.

Dole has taken advantage of the Philippines' cheap labor, low cost of land and large-scale plantations to overwhelm Taiwan overseas. Chao says Dole has also won over the Japanese by providing a steady supply of product, standardizing quality and offering compensation when shortages occur, while Taiwan remains obsessed with short-term pricing and has no long-term strategy.

"That's our most challenging problem," he says, and it may get worse.

With the domestic banana sector thoroughly defeated on the export front, its focus has turned inward, but that has not isolated it from outside competition. In fact, the fierce competition ravaging the industry entered a second round after Dole moved into Taiwan and sought a foothold in the country's middle and high-end banana distribution channels.

Interviewed together, the two industry veterans Chao and Lin expressed strongly divergent views of Dole's incursion into Taiwan's domestic market, where it has spearheaded the "single banana" business model by supplying bananas to 7-Eleven.

"Industry insiders believe that Dole is using a break-even strategy to expand its share of Taiwan's domestic market and control Taiwan's distribution channels, waiting for the day when Taiwan opens up banana imports so that it can bring in bananas from the Philippines," Lin says. At that point, he adds, Taiwan will face even stiffer competition.

Chao vehemently disagrees, bluntly telling Lin that he's wrong. Chao contends that Dole's presence has helped Taiwan's banana sector by promoting the sale of individual bananas at convenience stores and elevating the sector's output value. Also, when Taiwanese trading companies were attacking a new home-grown variety – the "Formosan banana" – Dole was helping Taiwan export it to Japan, Chao says.

But from Chao to Council of Agriculture chief Chen Bao-ji, nobody is willing to guarantee that if Taiwan joins the U.S.-led Trans-Pacific Partnership or the China-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (which are still under negotiation) it will not open its doors to bananas from the Philippines. The day will likely arrive, therefore, when Lin's concern of an invasion of Dole bananas from the Philippines turns into reality.

Consequently, every time a banana is sold at a convenience store in Taiwan, Taiwanese farmers become just that much more vulnerable to being replaced by their counterparts in the Philippines.

The Secret behind the Change in Strategy

Why did President Chain Store Corp., which operates 7-Eleven convenience stores in Taiwan, decide to work with Dole? CommonWealth reporters visited the company's headquarters on Dongxing Rd. in Taipei to uncover the secret behind the strategy of selling one banana at a time.

At the Taiwan Banana Research Institute in Pingtung County, experienced workers prepare bananas for export. But the facility symbolizes how far behind local processing facilities lag behind Dole’s.

At the Taiwan Banana Research Institute in Pingtung County, experienced workers prepare bananas for export. But the facility symbolizes how far behind local processing facilities lag behind Dole’s.

In 2011, when banana prices in Taiwan plummeted, President Chain Store launched a campaign to save the country's bananas, but its initial strategy of selling clusters of bananas as is done in traditional markets fell flat with consumers. Unwilling to accept defeat, the company put its mind to figuring out the best way to sell the fruit.

Liang Wen-yuan, the head of President Chain Store's fresh food division, says that when bananas were sold by the bunch, consumers would often not finish them all, leaving a few to go bad. By selling them individually, Liang says, consumers can buy a fresh, ripe banana every day.

But there was also the issue of price. A kilogram of roughly six to eight bananas costs NT$20 when bought directly from the farm, which translates to about NT$3 per banana. 7-Eleven charges up to NT$18 per banana, a mark-up that begs the question if there are bananas that are really that good. That's where Dole comes in.

Turning Bananas into a Specialty Product

When CommonWealth Magazine reporters visited Dole's facility in Beitou and observed the production line that supplies President Chain Store, the line was processing and repackaging bananas based on fresh food standards. The bananas shared a conveyor system with onigiri (rice balls of different shapes), indicating that they were clean to the point of being free of fruit flies. Though the fruit was fresh, its quality and cleanliness met cooked food standards.

Even more impressive, Dole is able to supply bananas to President Chain Store 365 days a year and adjust the supply based on actual sales. It's a major challenge because Dole has no way of knowing whether 7-Eleven will sell 80,000 or 100,000 bananas on any particular day, yet it must satisfy demand at all times. In other words, Dole must overcome such factors as typhoons or any other obstacles that might disrupt supply to keep bananas flowing to convenience stores as needed.

Liang says Dole has a week to prepare the bananas for sale from the time they are picked because they have a one-week ripening period, so meeting fluctuating sales volumes on a daily basis is extremely challenging.

"But this is value-added agriculture. You have to sort items into different grades and process them if you want to add value," he says. In the past it would have been unthinkable to have farmers wash their bananas one by one, but that is the product consumers now want.

When asked why President Chain Store decided to work with Dole rather than buying bananas directly from farmers, Liang says his company's priorities are quality and a steady supply.

"I also want to directly market farmers' produce, but the most important issue is whether or not farmers can deliver bananas as good as Dole's," he says.

Bananas are products of nature and cannot be controlled. They have different specifications and feature several seasonal variations in length and size, but the bananas Dole sells to 7-Eleven are nearly identical. It has worked hard to defeat nature and produce bananas year-round at a consistent price and quality level.

Taiwan’s banana hub of Cishan has become one of Dole’s main source of supply. It collects bananas in big trucks and sends them to its modern facility in Wanluan Township for processing.

Taiwan’s banana hub of Cishan has become one of Dole’s main source of supply. It collects bananas in big trucks and sends them to its modern facility in Wanluan Township for processing.

Taiwanese farmers, on the other hand, wait for natural disasters and typhoons to create major price fluctuations that deliver windfall profits. In addition, every farmer manages the land and uses pesticides in his own individualistic way, undermining the possibility of consistency on pesticide residues or quality. Under such circumstances, whether a kilo of bananas sells for NT$5 or NT$50 depends entirely on the whims of nature.

Farmers can still survive using their own quirky methods if they operate in a closed market, but they will have no way of competing against multinational corporations if the market is opened to imports.

Prior to last year, President Chain Store sourced all of its bananas from Dole, but in 2014 it began cultivating a second supplier – Taiwanese company Kisaraki Foods Co. – but Kisaraki Foods has a long way to go to catch up to Dole.

Dole's enterprise management and distribution approach has not only won over Taiwan's biggest convenience store chain but also Wellcome supermarkets and Costco.

Dole's Taiwan Farm Division?

In becoming President Chain Store's biggest supplier, has Dole really hurt Taiwan's banana farmers?

As soon as one enters Cishan at the foothills of Kaohsiung's mountain areas, one sees Dole's cargo trucks shuttling past Fengshan Temple, signaling the area that enjoys the status as Taiwan's best banana-growing region has become one of the major sources of supply for Dole.

With Taiwan having already ceded export markets to Dole, how do the area's farmers feel about giving up their crops for domestic sale to the multinational giant?

"Taiwan's banana associations have been undermined by Dole. If Dole's market share rises above 50 percent, it can control pricing. Once the small lizard has grown into a big dinosaur, Taiwan's banana farmers and trading companies will no longer be able to compete with it," says Chang Hong-shih, the head of the 36th Cishan Agricultural and Marketing Group.

Chang Hong-shih, the head of a Cishan Agricultural and Marketing Group, uses his own method to grow and sell bananas rather than competing with Dole. But he worries that the market will be one day controlled by Dole.

Chang Hong-shih, the head of a Cishan Agricultural and Marketing Group, uses his own method to grow and sell bananas rather than competing with Dole. But he worries that the market will be one day controlled by Dole.

In fact, Dole entered Taiwan relatively early, in 2005, when Taiwan liberalized its banana exports and prices collapsed. Dole quietly set up processing facilities in Beitou in the northern part of Taipei and in Wanluan Township in Pingtung County, and it is now planning a new facility in Zhuwei in New Taipei.

Golden Field's Lu, who cooperated with Dole years ago, says the multinational sold Taiwanese bananas and Philippine pineapples at the time, but the quality was inconsistent, and it struggled to make an impact here. The company only gradually gained strength in Taiwan when it began working with President Chain Store.

Because Taiwan still bans imports of Philippine bananas, Dole's strategy is limited to selling in Taiwan what it buys in Taiwan, Chang says. It buys bananas from local farmers, accelerates their ripening, sorts them into different grades, and cuts them into bunches of five to 10 bananas to sell to Costco or separates them one by one to sell to President Chain Store.

Chang, who once indirectly supplied Dole, says the company started out by working with local cooperatives and contracting them for supplies. But to lower production costs, it now signs contracts directly with farmers. Dole justifies the practice by saying it provides Taiwan's farmers with an income as stable as that of civil servants.

The Taiwan Banana Research Institute's Chao agrees, saying that farmers' ability to cooperate with Dole and receive a stable income represents a form of progress. But Chang is not sold.

"It sounds good, but farmers planting bananas for Dole means there's no winning or losing. They are tied down and simply collect a paycheck, essentially serving as employees on Dole banana farms," he says.

Chang prefers working hard to directly sell what he grows, even seeking out his own clients such as organic food stores or regular customers. Selling directly to clients means reducing the middleman's cut and increasing profits, a system, Chang says, that can easily deliver yearly incomes of over NT$1 million.

He worries, however, that if Dole continues to grow, farmers will not have any choice but to supply Dole because it will control distribution. Neither farmers nor farmers associations are united, making it impossible for them to compete with Dole, which will eventually manipulate the market.

"The farmers who are currently cooperating with Dole say Dole is very good and has consistently increased purchase prices. But, in fact, that's just luring farmers with some temporary benefits. When the volume of bananas cultivated gets bigger and you have to go through Dole to sell your crop, it will reverse its position and cut prices, the same way that big players on the stock market abuse retail investors," Chang says.

Taiwan can grow good bananas, but it has been unable to manage a brand or use modern marketing methods to sell bananas overseas.

Taiwan can grow good bananas, but it has been unable to manage a brand or use modern marketing methods to sell bananas overseas.

Wang Chi-wei, the leader of the Cishan band "Youth Banana" that sings about Taiwan's banana farmers and their products, says Dole also exports Taiwanese bananas, and if it were to become the international spokesman for home-grown bananas, it would be tantamount to having Dole decide their international price and image.

Even if these scenarios fail to materialize, Dole has already succeeded in haunting Cishan's banana farmers like a bad nightmare. And in view of the stiff competition that has come with the one-banana marketing strategy, Golden Field's Lu warns that Taiwan can no longer go along thinking that things are fine.

"Taiwan's bananas have great flavor. Older Japanese love them. We have to strive to get a new generation of Japanese to get to know our bananas in addition to Dole's," Lu says.

Back in Jiouru Township in Pingtung County, Taiwanese bananas are being packed into cartons destined for China – the first batch of home-grown bananas exported across the Taiwan Strait this year. Though Taiwan got the order because China has blocked imports of Philippine bananas because of the two countries' sovereignty dispute in the South China Sea, it behooves Taiwan to capitalize on the opportunity and rebuild the reputation of its bananas in China.

Dole may have severely bruised Taiwan's banana sector with its competitive edge, but it has also introduced new concepts and an impetus for change. If Taiwan can overhaul its systems and thinking, there may still yet be hope that a once powerful banana kingdom can rise up once again.

Translated from the Chinese by Luke Sabatier