History Resurfaces After Election

How the ‘1992 Consensus’ Colors Taiwan’s Fate

Source:Then ROC Vice President Lee Teng-hui and President Chiang Ching-kuo (Photo from CW archives)

The so-called “1992 cross-strait consensus” has once again become a hot topic in the wake of Taiwan’s recent elections. What is it all about, and how will it impact future cross-strait dynamics?

Views

How the ‘1992 Consensus’ Colors Taiwan’s Fate

By Chou Hui-chingweb only

At 8:00 p.m. on March 23, 1996, a clear evening, Lee Teng-hui, accompanied by family members to shouts of “Hello, Mr. President!”, slowly made his way to the stage at his presidential campaign headquarters on Bade Road in Taipei. Despite already having served as ROC President since the death of his predecessor Chiang Ching-kuo, this moment marked the very first time the 73-year-old truly felt like the president.

“Today is the most precious moment in our history. On this day, the twenty-third of March, 1996, the gates of democracy have been opened wide in the Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu region, with 21 million compatriots as the best witnesses,” Lee exclaimed from the rostrum. It was on this day that Taiwan completed its first presidential election by direct popular vote, marking the first time in greater Chinese history that the people elected their highest header. The Kuomintang (KMT) ticket of Lee Teng-hui and Lian Chan garnered 5,813,699 votes, a 54 percent rate of support, to become the ninth president and vice president of the Republic of China.

Journalists from over 500 media outlets worldwide gathered in Taipei, because while Taiwan conducted its first-ever direct popular presidential election, China was lobbing missiles into the sea off the coasts of Kaohsiung and Keelung, and conducting large-scale military exercises along Taiwan’s coastal territory. The tense situation across the Taiwan Strait grabbed the world’s attention, as economic development heated up on one side while democracy reached new heights on the other.

How did the cross-strait region become so close to blowing up and threatening global security?

Lee Teng-hui assumed leadership of the nation following Chiang Ching-kuo’s death at a more complicated time in world events. On the one hand, China was opening its doors and stepping out into the world. Meanwhile, on the other hand, the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union had ended, transforming relations between the two former superpowers.

In his memoirs, China Hands: Nine Decades of Adventure, Espionage, and Diplomacy in Asia, former director of the American Institute in Taiwan and U.S. ambassador to South Korea and China James R. Lilley revealed that Chiang Ching-kuo made the decision to nominate native Taiwanese Lee Teng-hui as his vice president and designated successor in 1984. In order to get Lee up to speed on the U.S.’s perspective, Chiang Ching-kuo asked Lilley to join Lee Teng-hui on a round-island tour in March of 1984. Accompanied by just their wives, Lee and Lilley toured the island, first going to Hualien before crossing over the Central Cross-Island Highway to Taichung.

I saw in him an effective politician, a man with a connection to the people who was not a conventional KMT leader. In public, he toed the party line, but in private he voiced strong opinions and was a Taiwan patriot. More so than his mainland Chinese colleagues in the Taiwan government, Lee identified with his people, and he believed in them. Yet at that time he showed no particular animus against China. In fact, he wanted greater contact with the mainland in the form of trade and tourism, but he was suspicious of China's desire to take over Taiwan, and he told me that his people would not accept China controlling Taiwan.

This is how Lilley described Lee Teng-hui after the two had spent every waking hour together for two days.

Congratulatory Telegram from Zhao Ziyang

China adopted a policy of opening up after Deng Xiaoping assumed power. Between 1978 and 1988, China recorded average annual economic growth of 10.2 percent. However, with a population of 1.3 billion, China had foreign currency reserves of under US$3.4 billion, and an average per capita GDP of US$370. When Lee Teng-hui retained his position as president in 1988, Chinese Communist Party Secretary General Zhao Ziyang sent him a congratulatory telegram as a show of goodwill.

Taiwan’s lifting of martial law and permitting citizens to visit relatives across the strait helped thaw cross-strait relations. Still, how to deal with China has always been a challenge for Taiwan’s leadership.

Chiang Ching-kuo maintained a “Three No’s” policy of no direct contact, no negotiation, and no compromise with the PRC, an approach rooted in the Chinese civil war. In contrast, Lee Teng-hui, who had never crossed swords with China, sought to ease cross-strait tensions, opting to promote pragmatic diplomacy and expand Taiwan’s international room to maneuver.

In March of 1989, Lee Teng-hui, described by local media as “the president from Taiwan,” made his first official visit to Singapore since assuming the presidency. In his formal invitation, the late Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew addressed Lee Teng-hui as “President of the Republic of China,” displaying utmost courtesy. Following the visit to Singapore, Lee Teng-hui made trips to the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, the United Arab Emirates, and Jordan, none of which had official ties with Taiwan, breaking considerable new diplomatic ground.

In May of 1989, Minister of Finance Shirley Kuo traveled to Beijing to attend the annual meeting of the Asian Development Bank representing “Chinese Taipei”. With this, Kuo became the first ministerial-level official of the Republic of China’s government to set foot on PRC soil since 1949, an act that stirred up considerable controversy in Taiwan. During the playing of the host country People’s Republic of China’s national anthem, Kuo stood and held her arms over her chest and chatted with fellow delegation members to show her position of non-recognition and protest. Consensus as to how officialdom from both sides of the strait should treat each other has long been lacking.

In the effort to address the explosion of illegal migrants from China following the lifting of martial law in Taiwan, representatives of the Red Cross from both sides signed the Kinmen Agreement in Kinmen in September of 1990, making the Red Cross the first window of communication across the strait.

In 1991, the Straits Exchange Foundation (SEF) and the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits (ARATS), representing Taiwan and the PRC, respectively, were founded. The establishment of the two quasi-official organizations superseded the Red Cross as the representative agencies of both governments for handling such everyday affairs as document verification, coordination and communication.

In spite of the establishment of agencies such as the National Unification Council, Mainland Affairs Council, and Straits Exchange Foundation for handling official cross-strait affairs under his administration, in private Lee Teng-hui had a secret channel for communicating with leaders across the strait. At the time, both sides shared an eagerness to lessen the chance of misunderstandings through proactive communication.

Then President Lee Teng-hui (Souce: CW)

Then President Lee Teng-hui (Souce: CW)

Secret Cross-Strait Communication Channel

The person in charge of running this secret cross-strait communication channel was Su Chih-cheng, who headed up the office of the president. A second trusted “secret emissary” was U.S. passport holder Cheng Shu-min, then director of the Chinese Television System (CTS) Planning Office.

“President Lee had multiple objectives in having myself and Director Su act together. Director Su’s identity was sensitive, preventing free entry and exit (to and from the PRC). He (President Lee) asked for my assistance to ensure Director Su’s safety. Director Su had to devote his undivided attention to negotiations, so he needed someone accompanying him not only to record the proceedings but keep a watchful eye on the overall situation. President Lee told me: “You have to prepare yourself mentally and be extremely cautious. If word gets out I will categorically deny everything,” revealed Cheng Shu-min to a Commercial Times reporter in 2000.

China’s counterparts to Su Chih-cheng and Cheng Shu-min included Yang Side, director of the Central Taiwan Affairs Office on behalf of former President Yang Shangkun, ARATS director Wang Daohan, and Zeng Qinghong, director of President Jiang Zemin’s office.

According to the Chinese-language book True Confessions of Lee Teng-hui’s Administration, Lee authorized Su Chih-cheng to meet with his PRC counterparts in Zhuhai, Hong Kong, and Macao on 27 occasions. The first nine of the talks were attended by author and scholar Nan Huai-chin, who acted as a mediator; the subsequent 18 meetings were arranged directly.

Over the course of initial high-level communications, both sides worked hard to establish a foundation agreeable to each of them. In September of 1992, the National Unification Council passed a resolution entitled “On the Meaning of One China”, the first part of which contained the crucial statement: “Both sides on either side of the Taiwan Strait adhere to the principle of ‘One China’; however, each side ascribes different meaning to it… Our side holds that ‘One China’ should refer to the Republic of China, which has existed since its founding in 1912, whose sovereignty extends to all of China, but currently governs only the territories of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu. Therefore, Taiwan is a part of China, but the mainland is also a part of China.” This resolution became known as the consensus within Taiwan of “one China, different interpretations.”

“Generally speaking, two main principles ran through the KMT’s thinking towards the administration of cross-strait relations, namely ‘democracy’ and ‘parity’. ‘Democracy’ meant taking responsibility for popular opinion; while ‘parity’ meant that both sides must act as equals,” notes Su Chi, former minister of the Mainland Affairs Council under Lee Teng-hui’s administration.

Cross-Strait Parity, Koo-Wang Summit

The first official meeting between officials on both sides of the strait since 1949 took place in Singapore in April of 1993, with SEC Chairman Jeffrey Koo representing the ROC and ARATS Chairman Wang Daohan representing the PRC. Su Chi, then a professor at National Chengchi University, was present at the summit as an observer, witnessing the elaborate arrangements both sides undertook to ensure equality during the talks.

For instance, in the effort to satisfy Taiwanese popular opinion, both sides agreed to hold three daily press conferences, at noon, early evening, and after dinner, all timed to match different media programming schedules. Great pains were taken to uphold parity at the pressers, such as who spoke first and for how long at each press conference.

In addition, both sides had to sit facing each other at opposite ends of a long conference table. Before commencing each round of talks, Koo and Wang had to stand, extend their hands across the table and shake hands, then face one side with personable smiles on their faces before turning to face dozens of cameras on the other side. The picture presented on television screens and newspaper pages was that of cross-strait parity. Another detail concerned Chinese convention, which holds that the seat to the right has particular distinction. Accordingly, in the name of equality, Koo and Wang had to swap seats repeatedly during signings so as to prevent either party from dominating the right-hand position at the signing table.

Just as cross-strait communications seemed to be getting on track, Lee Teng-hui’s 1995 visit to the United States provoked China to literally go ballistic and fire missiles into Taiwan’s territorial water, thus setting relations back considerably. “Prior to (Lee’s visit to) Cornell, cross-strait relations leaned closer towards peace than conflict, and tactically Taiwan was the more proactive party. When the script flipped and conflict outweighed peace, Beijing took the driver’s seat, and Taiwan assumed a passive stance. As time went on, the ever-important U.S. factor played an increasingly direct role,” stated Su Chi, offering his take on the changes engendered by the three-way relationship between Taiwan, China and the United States.

Cross-strait relations have never been a simple matter between Taiwan and the PRC, but rather a trilateral relationship between the U.S., Taiwan, and the PRC, with the U.S. setting the course. Maintaining the stable operation of this three-way relationship has to date been in the best interests of the U.S., and the “One China” policy is the most critical pillar of the U.S.’s cross-strait policy, which states: “The United States acknowledges that all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan strait maintain there is but one China and that Taiwan is a part of China. The United States government does not challenge that position.” Prior to the normalization of relations with the PRC, the Republic of China represented China under the U.S.’s One China policy. Since the U.S. and the PRC established official diplomatic relations in 1979, the PRC has represented China under the U.S.’s One China policy.

The Cold War ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, eroding the three-way relationship the U.S., Soviet Union, and China had maintained since the Nixon era. With this, Washington no longer needed to play the China card against the Soviet Union, and Beijing no longer needed to use the America card against Moscow. After the U.S. imposed sanctions against China following the Tiananmen Square incident, Deng Xiaoping told former President Nixon: “Don’t look for China to plead with the U.S. to lift sanctions. China will never bow down, even if they remain in place for 100 years.” And with this, Washington and Beijing entered the 1990s as an era characterized by mutual distrust and suspicion.

Trilateral relations between the U.S., Taiwan and China tilted somewhat towards Taiwan following the June Fourth Incident, as U.S. President George H.W. Bush lent his support to Taiwan’s participation in international trade organizations, including supporting Taiwan’s entry into the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1990 under the title of “the Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu”; Taiwan’s membership in APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) bid in 1991 under the name “Chinese Taipei”; and the sale of 150 F-16 fighters to Taiwan, announced in September of 1992. (Read: From GATT to WTO, Taiwan’s Global Chess Match)

Bill Clinton, who had previously visited Taiwan, took office as President of the United States in 1993. Clinton had praised Taiwan’s democratization both before and after his election to the presidency, giving rise to hope in Taipei of improved relations with Washington.

Translated by David Toman

Edited by Sharon Tseng

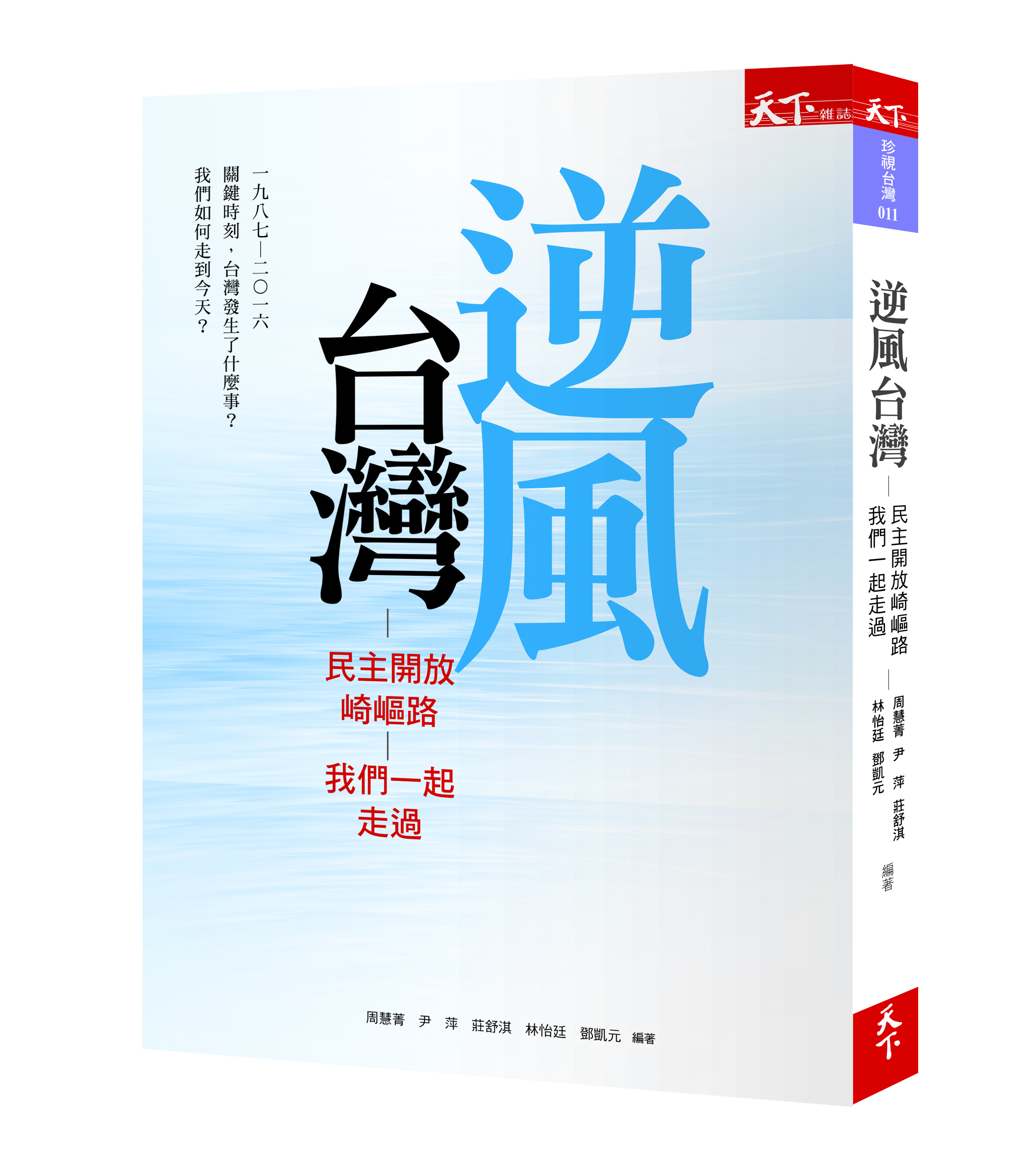

The original article is a sneak-peek extract from the following book, which will be published by CommonWealth Magazine on Dec. 25, 2018.