Taiwan’s First Directly Popularly-Elected President

From Constitutional Reform to Democracy

Source:CW Archives

Having hurriedly assumed the top seat of power, Lee Teng-hui rapidly set about pushing forward democratic reforms in Taiwan, becoming Taiwan’s first directly popularly-elected president. Yet populism and money politics reared their ugly heads from time to time on the road to democratization.

Views

From Constitutional Reform to Democracy

By Chou Hui-chingweb only

At 8:00 o’clock on the evening of January 13, 1988 on the grand veranda of the presidential office building, with Judicial Yuan Minister Lin Yang-kang presiding, 65-year-old Vice President Lee Teng-hui took the oath of office to become President of the Republic of China on Taiwan, just four hours after the sudden death of President Chiang Ching-kuo.

The hearse carrying late President Chiang Ching-kuo (Source: CW archives)

The hearse carrying late President Chiang Ching-kuo (Source: CW archives)

Starting from the next day, and every morning for 13 consecutive days thereafter before going to work, Lee Teng-hui and his wife, Tseng Wen-hui, paid their respects to the late President Chiang in state at Taipei Veterans Memorial Hospital.

“I took pains to show respect in order to show that I would never veer from the course he set, that I would abide by his teachings, and make assurances that there would not be excessive changes. It was intended to help make people feel secure and calm. Over the two-year, four-month period as interim president I was always contemplating matters, but first I just settled down to think quietly, just as the skies are quiet for a spell before a typhoon arrives.”

For Lee Teng-hui, who suddenly stepped in as president following three years and eight months as vice president alongside President Chiang Ching-kuo, the most important consideration was maintaining political stability.

Chiang Hsiao-yung, Ching-kuo’s youngest son, who often accompanied his father late in life, wrote in a book he authored: “The choice of Lee Teng-hui as vice president was made because, unlike others like Lin Yang-kang or Chiu Chuang-huan, he did not carry a strong association with a local faction, and what’s more, he had an American Ph.D. Senior (KMT) party big wigs like Huang Shao-ku and Sun Yun-hsuan also agreed after much consideration that Lee Teng-hui was the best choice.”

Lee Teng-hui was fortunate to inherit from Chiang Ching-kuo a stable polity in which democracy had been set in motion under a climate of economic prosperity. (Read: Chiang Ching-kuo's Crucial 200 Days) This gave him time for reflection and gathering his thoughts before setting out to consolidate his authority step by step. At the time of Chiang Ching-kuo’s death in January of 1988, Taiwan’s foreign exchange reserves of US$75 billion ranked second in the world, annual economic growth exceeded 10 percent, the average per capita annual income was US$6,000, unemployment was 1.97 percent, and Taiwan was the world’s leading producer by volume of seven information electronics product categories, including computer terminals, displays, telephones, and calculators.

“At the time of Chiang Ching-kuo’s death, it was impossible to see what would become of Taiwan. People had all kinds of different expectations, but there were too many uncertainties.” When Lee Teng-hui unexpectedly assumed the presidency, both his and Taiwan’s futures were uncertain. “I’m just one person, without a posse and without connections to the intelligence community or support from the military. One could say that I have nothing. The same is true within the party (Kuomintang); it’s completely beyond my control. I’m essentially a prototypical puppet, and as a puppet all I can do is play the role of a puppet,” admitted Lee Teng-hui in his first-hand account Chiang Ching-kuo and Me, in which he candidly described how he felt upon suddenly assuming the presidency.

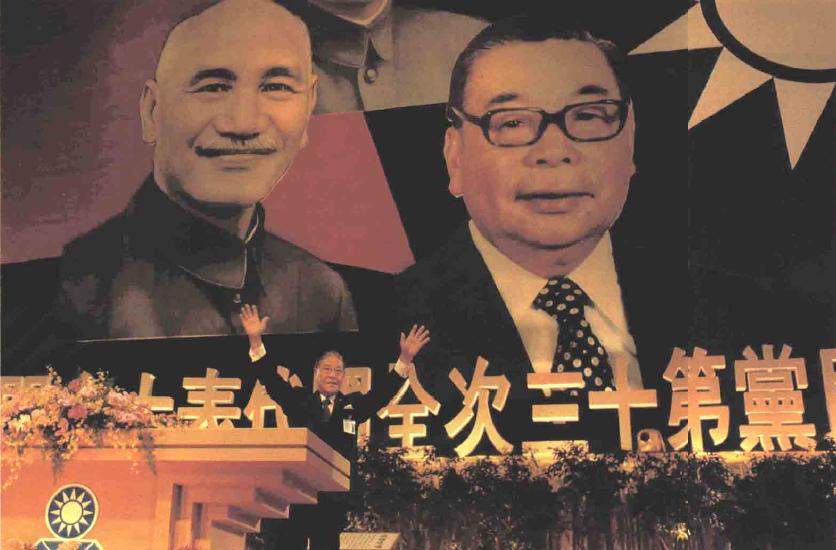

Lee Teng-hui in front of a poster of Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo (Source: CW archives)

Lee Teng-hui in front of a poster of Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo (Source: CW archives)

The year 1989 was a watershed in world history. In May of that year, the leader of the Soviet Union visited China for the first time after 30 years of sour relations. As Deng Xiaoping and Gorbachev held a summit inside Beijing’s Great Hall of the People, throngs of students and citizens gathered outside in Tiananmen Square and held hunger strikes demanding reform and calling for Deng Xiaoping and Premier Li Peng to step down. Holding an image of Gorbachev, they shouted: “In the Soviet Union they have Gorbachev… in China, who do we have?”

A CommonWealth writer was there at Tiananmen Square as the events unfolded. One hunger striking youth told this visitor from Taiwan: “I can see right through them. Whatever happens, don’t let them ‘liberate’ Taiwan.” On June fourth, People’s Liberation Army troops and tanks entered Tiananmen Square. Following the events that transpired, numerous Western nations responded by enacting economic sanctions against China.

A few months later on the other side of the globe, people filled Berlin’s Potsdamer Platz to celebrate the fall of the Berlin Wall under a democratic tide across several Eastern European countries in succession. Just two years later, the Soviet Union also collapsed, ending the Cold War that had pitted East against West for nearly 75 years. These developments were seen worldwide as a victory for U.S.-led capitalism, Western-style freedom and democracy and the market-based system, and the final nail in the coffin of ideology. American scholar Francis Fukuyama was moved to place a footnote on the tide, calling it “the end of history.”

As momentous change unfolded around the world, Taiwan quietly underwent its own democratic reform. Proficient at leveraging momentum and exploiting internal division, Lee Teng-hui was able to gradually erode the power of the Kuomintang old guard and bring party, government and military power to his side. Taking advantage of the appointment of a new premier, he was able to get Yu Kuo-hua, Lee Huan, and Hau Pei-tsun, old guard members who controlled finance, the party, and military, respectively, to slowly relinquish power. Upon his resignation from the premiership in May of 1989, the ordinarily laconic Yu Kuo-hua exclaimed during a television interview, “Politics is too frightening!”

As the president was up for election once again in March of 1990, 700 “senior” members of the National Assembly, a body that had not undergone a new election in nearly half a century, resolved to extend representatives’ terms another nine years while voting themselves an attendance remuneration increase to NT$220,000, causing widespread anger and indignation across society.

On March 16, Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) Chairman Huang Hsin-chieh, protesting the National Assembly’s expansion of powers in front of the presidential office, was forcibly removed by military police. Later that afternoon, a group of National Taiwan University (NTU) students, holding simple white banners and placards, began staging a sit-in at the square in front of Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall, not far from the presidential office building.

A group of students staging a sit-in at the square in front of Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall (Source: CW archives)

A group of students staging a sit-in at the square in front of Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall (Source: CW archives)

Over the course of the following six days, over 5,000 students from 28 colleges and universities around Taiwan joined the sit-in, during which students raised four main demands - dissolve the National Assembly, abolish the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion (note: the provisions were essentially a declaration of war against the Chinese Communists, effectively continuing China’s civil war), hold a national affairs conference, and set a political and economic reform timetable. In addition, they sought to engage in dialogue with President Lee Teng-hui.

The movement, which became known as the Wild Lily Movement, was Taiwan’s first large-scale student movement.

Many citizens chipped in a few dollars here and there for the students to buy tents and rain gear. For Chiu Yu-pin, chief marshal of the event, the most memorable occasion involved an elderly veteran from China who went up to the donation box with his life savings in the form of gold jewelry. When student marshals prevented him from dropping them in the box, he got down on his knees and in thickly accented Mandarin, said: “Young people, this has been my lifelong hope, and I’ve finally waited for this day to arrive. Won’t you allow me to lend my support to you with it?” With this, the entire squad of marshals knelt with him and, overcome with emotion, began to cry as well.

On the evening of the twenty-first, Lee Teng-hui received 50 student representatives, promising to hold a national affairs conference and setting a series of democratic reforms in motion. During his inauguration on May 20 as the eighth President of the Republic of China, Lee Teng-hui announced that he would oversee “the termination of the Temporary Provisions within a year, and hold an election for the full-scale remaking of the National Assembly within two years.”

The Wild Lily Movement (Source: CW archives)

The Wild Lily Movement (Source: CW archives)

After becoming the eighth ROC President, lee Teng-hui convened a national affairs conference to build consensus for reform, leveraging opposition party power by activating inter-party consultation and negotiation. The national affairs conference marked the first time political consultation took the form of a national conference, placing political reform on the table for discussion, and reaching major conclusions including the direct popular election of the president, the timely retirement of senior central government representatives, the popular election of the provincial governor, and abolishment of the Temporary Provisions. President Lee leveraged the national affairs conference as an endorsement of his constitutional reform program.

Taiwan announced the end of the Period of National Mobilization in the Suppression of Communist Rebellion and the Temporary Provisions in May of 1991, signalling a return to constitutional government. With this, the government in Beijing was no longer a rebel group, but an equal political entity.

China once again put economic reform into motion in 1992. On the second day of the year, 88-year-old Deng Xiaoping embarked on his “southern tour”, visiting Wuhan, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, and Shanghai and making major speeches on reform and opening at each stop. Deng stated, “Failure to adhere to socialism, develop the economy, and improve the people’s lives would be a dead end,” announcing that he would continue to deepen opening and reform. The previous year, Shanghai mayor Zhu Rongji had been transferred to Beijing to serve as vice premier, overseeing the economy. It was Zhu who began setting up a capitalist market and conducting the reform of state enterprises.

Taiwan Accelerates Political Reform While China Focuses on Economic Reform

The early 1990s saw a number of democratic firsts transpire in Taiwan: The entire body of the National Assembly was popularly elected for the first time, as were members of the Legislative Yuan; in 1994, the mayors of Taipei and Kaohsiung, municipalities under direct central government jurisdiction, were popularly elected once again, as was the provincial governor, and the president was popularly elected for the first time in 1996.

With the direct presidential election, Lee Teng-hui became the first popularly elected president in Greater China, earning him the nickname “Mr. Democracy” from TIME magazine.

“Today is the most precious moment in our history. On this day, the twenty-third of March, 1996, the gates of democracy have been opened wide in the Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu region, with 21 million compatriots as the best witnesses.” Having received 5,813,699 votes to become the ROC’s first popularly elected president, Lee Teng-hui and Vice President-elect Lien Chan celebrated their victory at KMT party headquarters, after which they proceeded to their campaign headquarters, where Lee made the above statement.

Over the course of democratization and localization, Lee Teng-hui progressively consolidated power in his own hands. The New Kuomintang Alliance, a faction within the KMT, defected during the party’s Fourteenth Party Congress in 1993 to form the New Party. For the first time, the KMT made Legislative Yuan members, National Assembly representatives, and provincial and city council members “automatic party delegates”. Lee Teng-hui was similarly elected party chairman by party delegates, putting him firmly in control of the party machine. Further, Lee took advantage of constitutional revisions and expanded presidential powers to become a “strongman president” in his own right.

During his remarks upon assuming the chairmanship of the DPP on July 1, 1996, Hsu Hsin-liang stated: “Following the direct popular election of the president, we in Taiwan no longer face an ‘illegitimate foreign regime’ but a legitimate president and ruling party with popular support. Accordingly, we must adjust our political attitudes. We must compete with the ruling party for the understanding and support of the Taiwanese people… The future relationship between domestic political parties should be ‘one both of competition and cooperation’ as is normal in a democracy.” That same evening, Lee Teng-hui held a dinner at his residence for Hsu Hsin-liang, at which the two enjoyed a vigorous discussion about inter-party cooperation, promoting healthy party politics, and continuing to promote political reforms. This dialogue would eventually set the stage for the two parties to work together to enact constitutional revisions the following year.

Amid considerable chaos, the National Assembly passed provisions for a new Constitution on July 18, 1997, completely reworking the operational mechanism of the ROC government. The constitutional revisions were extensive, with impact of unprecedented magnitude. With the Legislative Yuan’s power of approval over the nomination of premier having been rescinded, the president was free to appoint the premier, whose status was diminished to become “executor of the president’s policies.” Still, as the nation’s highest administrative official, the premier could potentially be subject to a vote of no-confidence by the Legislative Yuan. This made the position of premier one of “accountability without authority,” while presidential powers were expanded without checks and balances, giving the president “authority without accountability.”

The Constitutional Revision Monitoring Alliance, a private organization, strongly criticized that set of constitutional revisions, calling it “an ugly farce full of political parties and politicians meeting to discuss how to divide their spoils,” as well as noting the president’s sole grasp of power, the fragmentation of executive power, diminishment of legislative power, and violating the spirit of democratic oversight and checks and balances.

Over the course of moving forward Taiwan’s democratization process, Lee Teng-hui also fortified populist politics. Kuo Cheng-liang, former executive director of the DPP’s Policy Council, relates that the essence of populism is that it stresses direct resonance between political leaders and the public. Political leaders appeal to their personal charisma in the attempt to arouse responses from the public. “Lee Teng-hui is the originator of populism in Taiwan,” because Lee Teng-hui looked to channels outside the established order, such as going around the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to use Liu Tai-ying as an emissary to lobby the United States to engage in “head of state diplomacy”; going around the Ministry of Education to form a private sector educational reform committee to push educational reform; and going around the Council for Cultural Affairs to set up the quasi-official Cultural Affairs Headquarters to promote the localization movement.

Hu Fu, a scholar of political science, once noted an unusual phenomenon in Taiwan’s political development, namely that the more democracy is promoted, the more it engenders conflicts of national identification. And this sort of democratization process is naturally full of complexity and threats. (Read: Remembering Hu Fu: Democratic Trailblazer and the Conscience of a Generation)

Translated by David Toman

Edited by Sharon Tseng

The original article is a sneak-peek extract from the following book, which will be published by CommonWealth Magazine on Dec. 25, 2018. Find more excerpts in How the ‘1992 Consensus’ Colors Taiwan’s Fate, and From GATT to WTO, Taiwan’s Global Chess Match.