Get-Rich-Quick Tales from the 1980s

How Rich Was Taiwan?

Source:CW archives

The nation was dubbed “the Republic of Casino” by astonished foreign media, and just about every Taiwanese was a gambler.

Views

How Rich Was Taiwan?

By Chou Hui-chingweb only

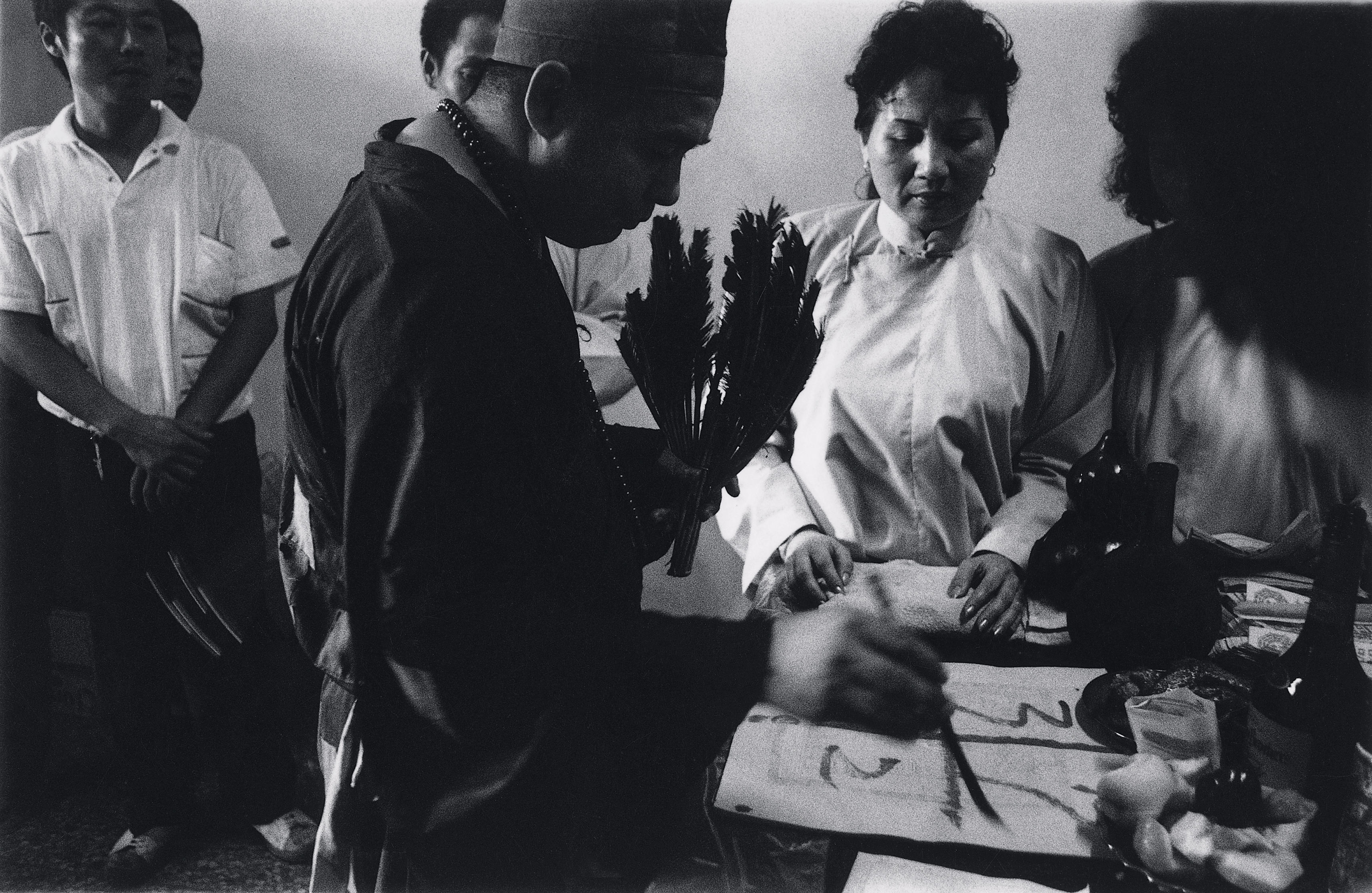

Seven bodies lay cold beneath a lonely cemetery at the foot of Baguashan in Changhua County. But at the midnight hour, ten thousand living souls gathered aboveground. Disciples lit incenses and muttered incoherent prayers, leering at a pan of sand at their feet where divinely lucky numbers were supposed to appear. The 1981 movie “The King of Gambler” played to the gathering crowd in a nearby roadside theater. Eager to make a quick buck, street vendors flocked to the peripheries, hawking meatballs, winter melon tea, even incense and ghost money.

“Rubberneckers crowded around traffic accidents not to lend a hand, but to observe the blood spray like modern haruspices. Temple dwellers froze at the sight of ash falling from burning incense—perhaps winning lottery numbers would be traced in the dust.” Artist Shing-Shyong Lin, who illustrated the state-sponsored lottery tickets for the Bank of Taiwan, was kidnapped three times in 18 months by maddened gamblers who were convinced he had some inside knowledge. “It was insanity!”

The sweepstakes game “Da Jia Le” (大家樂; lit. “everyone is happy”), an illegal lottery not sanctioned by the Taiwanese government, launched in July or August of 1985. It spread like wildfire through the nation, catching fire especially in Central and Southern Taiwan. It was easy to play, offered large cash rewards, and the chance to win was as high as 3%. For as little as 300 or 500 Taiwan dollars, you picked one of a hundred numbers from 00 to 99. Da Jia Le piggybacked on the concurrent state lottery “Patriotic Lottery” (愛國獎券); its winning number was the last two digits of the winning number for the Patriotic Lottery’s second prize. The jackpot was 15 to 19 times the price of entry, making it far more popular than its state-sponsored rival.

It was a period when Taiwan was flush with hot money. The booming economy had dumped 500 billion Taiwan dollars in the postal savings fund, and another 2.5 trillion in other forms of private funds. People wanted to invest, but in what? The nascent stock market was unprepared, and you could not trust banks. So a game of chance became the popular outlet, and cash poured into Da Jia Le.

It is impossible to know how much capital wound up in the illegal sweepstakes. An unofficial estimate by the provincial government put the number at 300 million Taiwan dollars per drawing. As there were three drawings each month, the annual number was a staggering 10 billion. “Just about everyone was illegally gambling,” said a police officer from Central Taiwan. Gamblers came from all walks of life, with 90% of them occupying the middle and lower rungs of the social ladder.

Another reason Da Jia Le flourished in the summer of 1985 was the beginning of the economic slump and rising unemployment rates. In August of 1985, the unemployment rate increased to a decade-long high of 4.1%. That meant there were 320,000 unemployed Taiwanese walking the streets. A middle-aged bookie in Changhua used to collect scrap metal. He once made a comfortable 40 to 50 grand a month, but when the slowing economy reduced that number to only 10 to 20 grand, he threw in with the illegal gamblers and increased his monthly earnings to over a hundred thousand.

Ultimately, unsanctioned gambling ceased when the government showed moral leadership. Provincial governor Chiu Chuang-huan ended the state-sponsored Patriotic Lottery in 1987, effectively ending Da Jia Le as well. But gamblers needed their fix, so all the hot money simply went to the next big game.

The height of Da Jia Le mania (Source: CW archives)

The height of Da Jia Le mania (Source: CW archives)

Underground Investment Companies: Burning Down the House

Another ten thousand entrepreneurial souls gathered on November 20th, 1988, this time in the Zong-Hua Stadium in Taipei City. It was the 4th annual sports meet held by Taiwan’s largest investment firm: Hong Yuan Group (鴻源機構). Despite protests from stadium security, exuberant investors lit fireworks that ultimately burned off the stadium’s roof. Chief of the Group was Shen Chang-Sheng (沈長聲), who had ties to a Taiwanese triad society, the Four Seas Gang. Together with co-conspirators Liu Tie-Qiu (劉鐵球) and Yu Yong-Ming (於勇明), he established what was essentially a pyramid scheme. Billions of dollars poured in, and other underground investment companies sprung up to emulate Hong Yuan’s success.

The underground investment companies of the late 1980s offered a lucrative 4% interest rate. What’s more, they provided employment. In the case of the giant Hong Yuan, investors were invited to sign up as a member of the staff. The starter package required you to invest 150,000 Taiwan dollars, but every month you got 5,000 in interest and a salary of 7,000. If you invested 1.5 million, you became a corporate “specialist” and got 60,000 in interest on top of your monthly salary of 30,000, which ballooned your monthly income to almost 100,000. Veterans and retired public servants with money in the bank stampeded to join these shady investment firms, eager to begin their “second careers”.

It is estimated that Taiwan had as many as 180 underground investment companies in 1989. Together, they fleeced 1.2 million investors for over 199.3 billion dollars. The booming stock and real estate markets were hotbeds for these investment firms; one might even say the investment firms inflated stocks and housing prices for their own profit.

Hong Yuan CEO Liu Yongan (劉永安) famously said, “Isn’t the stock market just an open casino? Why should we be prosecuted for making money legally?”

Giant underground investment groups like Hong Yuan and Long Xiang (龍祥) could influence stock prices or even elections, making it doubly difficult for the government to crack down on them.

The Taiwanese underground investment companies were products of a time when an abundance of capital combined with the lack of regulation to brew up the perfect storm. But the pyramid scheme collapsed once laws were put in place. On June 30th, 1989, The Banking Act of The Republic of China was passed, and the crackdowns began. In January 1990, 160,000 investors lost their money when Hong Yuan folded. Of the 94 billion Taiwan dollars amassed by Hong Yuan, only 4 billion was recovered. The mastermind Shen Chang-Sheng was sentenced to seven years in prison and fined 3 million Taiwan dollars.

“Hong Yuan played mind games around its investors,” said Kwang-Kuo Hwang, professor of psychology at National Taiwan University. Investors were inundated with rags-to-riches stories and felt pressured to get in on the action. Hong Yuan seduced them with a chance to get rich quick. Of course, when the bubble burst, the investors lost both their dreams and money.

Beggars on the Boulevard: When Property Prices Doubled Every Year

The year was 1989, and 37-year-old Lee Hsing-chang (李幸長) was an ordinary schoolteacher working in Sinpu Elementary School in Banqiao. The previous year, he had sold his house in exchange for more modest accommodations and more cash in hand; he wanted to study for a master’s degree, and there was a child on the way. But in six months, the house he sold for 1.6 million Taiwan dollars was back on the market for 3 million dollars, and he could no longer afford even a much smaller apartment.

“I held a press conference with friends and other teachers to express outrage. People began to take notice,” said Lee. Together with friends and colleagues from Sinpu Elementary School, they launched the “Snails Without Shells” housing movement in May of that year. Lee went from being an ordinary schoolteacher to the voice of housing rights activists across the country, because soaring housing prices were about to take their toll on the Taiwanese economy.

On February 27th, 1987, the National Property Administration in the Ministry of Finance auctioned off a piece of land measuring about 5,620 square meters, located near China Airlines on Section 3 of Nanjing E. Road in Taipei. The amazing thing was the winning bid of 150 million Taiwan dollars from Cathay Life Insurance Company was three times that of the opening price. Property owners took notice. The great house price inflation of Taipei had begun.

Property prices across Taiwan tripled in two years. In Taipei, they increased by a factor of 4.5 in four years. The asking price per ping (equals 3.3 square meters) of new or presold houses in Taiwan went from 60,000 Taiwan dollars in 1987 to 190,000 in 1989. In Taipei, it went from 67,200 in 1986 to 368,700 in 1990—an increase by a factor of 5.49.

One of Taiwan’s first civil protests after martial law was lifted in 1987 was spearheaded by the schoolteacher Lee and his ragtag band of activists. These elementary school teachers handed out flyers and hosted events, launching the “Snails Without Shells” housing movement that combats exorbitant property prices to this day. (Read: Lifting Martial Law and Opening-up Taiwan)

“The homeless have their pick of streets to sleep on, and we picked the most expensive street in Taiwan!” On August 26th, 1989, the landmark Snails Without Shells demonstration saw more than 50,000 protesters camping out on Zhongxiao E. Road, where the priciest condos in the country were located. This was Taiwan’s first urban reform movement, and still the largest to date.

The “snails” owned the streets, but there was no violence, and they shunned political endorsement. “We are all middle class folks,” explained Lee Hsing-chang.

Snails Without Shells on Zhongxiao E. Road (Source: CW archives)

Snails Without Shells on Zhongxiao E. Road (Source: CW archives)

The Soaring Stocks and the Hundred Grand Tip

It was 15 days after the Tiananmen Square massacre. Nine fifty-five in the morning on June 19th, 1989. Taiex (Taiwan Stock Exchange) officially broke 10,000 points. Cue cheering, applause, popping champagne.

It was an age of mad growth. The Taiex went from 1,000 points in 1986 to 12,000 in 1990. Stock prices multiplied by more than twelve times in less than four years.

In 1985, there were only 400,000 investors and 127 listed companies on Taiex. In 1990, there were 199 listed companies, but the number of investors had skyrocketed to 5.03 million—basically a third of all Taiwanese over the age of 15. Trading stocks had become the national pastime. Changes in stock prices made all the headlines, and on every street corner there were tabloids and magazines boasting secret knowledge of how to win at stocks. The most popular seminars across the nation were about investing in stocks. The spectacle even attracted Japanese TV stations to fly in a team of reporters to observe the madness.

The revaluation of the Taiwan dollar opened the floodgates to a deluge of “hot money” eager to profit from arbitrage, further raising stock prices. Plummeting interest rates, unseen since Taiwan was liberated from Japan after the Second World War, catapulted bank savings into the stocks. Buying just about any stock netted you a profit. The tantalizing chance to get rich quick had everyone entranced. Job openings remained vacant across the country. Only fools worked for an honest salary.

By ten thirty in the morning on a working day, growing stock prices would hit the daily price fluctuation limit, and the market would close early. Investors and stockbrokers pat themselves on the back and retired for an early lunch. Every day was essentially a half-holiday. Housewives shopped, had afternoon tea, sang, danced, or enjoyed spas after the market closed. The newly rich delighted in flaunting their wealth. Three thousand Mercedes-Benzes were purchased that year, briefly making Taiwan the second largest market in the world. People lined up to buy mink coats worth tens of thousands of Taiwan dollars. Restaurants selling delicacies such as 15,000-dollar abalone or 36,000-dollar bear paw dishes were packed with wealthy diners. The Asian arowana fish, colloquially called the “red dragon”, was a popular pet. They cost about as much as the mink coats.

Moneyed businessmen congregated in five-star lounges. All along Nanjing E. Road, from Brother Hotel to (the now nonexistent) Huanya Hotel (環亞飯店), a swath of ritzy lounges cropped up, with the two most expensive being “Hua Zhong Hua” (花中花) and “Dafuhao” (大富豪). Inside, the wealth on display was obscene. Stacked dollar bills propped up wobbly table legs. Greeters at the door were gifted ten thousand dollars each by generous patrons. Waiters were tipped with six-digit checks.

The nation was dubbed “the Republic of Casino” by astonished foreign media, and just about every Taiwanese was a gambler. The government was powerless to intervene. In July of 1988, President Lee Teng-hui appointed Shirley Kuo as Minister of Finance. To control the stock market bubble, Kuo announced a tax on gains derived from securities transactions, to be put into effect the following year. The stock market imploded. Taiex plummeted for 19 straight days, reaching a low of only 4,873 points. Investors took to the streets and laid siege to the Ministry of Finance as well as Kuo’s residence. Legislators took their side and held the government accountable. Fearful of losing next year’s elections, the government backed down and canceled the tax. Stock prices exploded with renewed fervor, hitting a record-high of 12,682 points in February of 1990. (Read: Lee Teng-Hui: From Constitutional Reform to Democracy

But the stock market is described as a bubble because it inevitably bursts. The day of reckoning was not long in coming. In October of 1989, Taiwan was removed from the United States’ list of currency manipulators. Revaluation of the Taiwan dollar halted, and hot money began seeping out. In January 1990, the Nikkei took a leap after attaining a historical high. The Taiex followed suit after its peak in February. The beginning of the Gulf War in August hiked up oil prices, and Taiex bottomed out at merely 2,485 points in October.

In other words, the stock market shed 10,000 points within a span of eight months. Five million investors woke up with their accounts depleted. Shea Jia-dong, who served as deputy governor of the Central Bank of the Republic of China from 1996 to 2000, pointed out that the crash was cushioned by the fact money for stocks and property came out of investors’ personal savings, so the impact on Taiwan’s economy and employment was not as drastic as it could have been.

But society’s moral fiber was indubitably corrupted. Traditional values such as an honest day's work for an honest day's pay gave way to a prevalent get-rich-quick mentality. This had lasting repercussions on Taiwan’s professional dedication, work quality, food safety, and even law and order, from those heady days all the way up to our current age.

Translated by Jack C.

Edited by Sharon Tseng

The original article is a sneak-peek extract from the following book, which will be published by CommonWealth Magazine on Dec. 25, 2018. Find more excerpts in From Constitutional Reform to Democracy and How the ‘1992 Consensus’ Colors Taiwan’s Fate.