How Taiwan’s Small-town Factories Keep Making the World’s Money

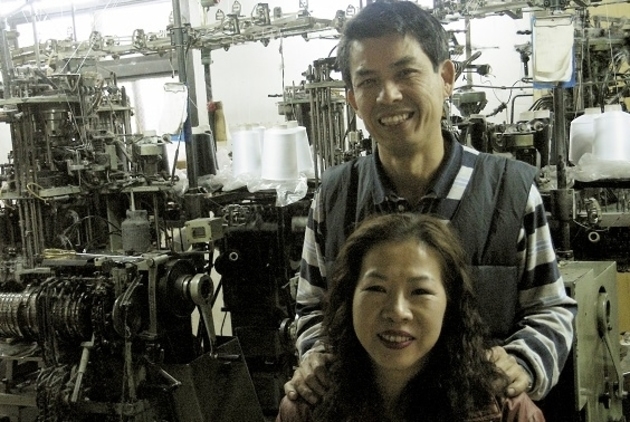

Source:CW archive

Taiwan may be known as a high-tech haven, but clusters of small, unsung factories hidden in small towns around the country remain important sources of export revenue. How have they survived in an age of globalization and fierce competition?

Views

How Taiwan’s Small-town Factories Keep Making the World’s Money

By Kaiyuan TengOpinion@CommonWealth

Driving along a narrow agricultural road no more than a car wide that runs along guava fields, CommonWealth reporters arrive at He Yue Industry in the heart of Taiwan’s sock and hosiery production hub – Shetou Township in Changhua County.

During Shetou’s heyday, one of every two of the town’s 40,000 people was dependent economically on the hosiery industry and the more than 400 “factories” in Shetou and the neighboring towns of Yuanlin, Tianzhong, Beidou and Ershui pumping out socks and pantyhose to global markets.

The production facilities were not factories in the traditional sense. They were more farmhouse, family residence and workshop merged into one, epitomizing both Shetou at the time and Taiwan’s traditional spirit of hard work and putting everything into the family business.

A common refrain heard in the town is that “Shetou has three ‘many’s’: many socks, many guavas and many chairmen of the board,” referring to the many small business owners there.

The 65-year-old owner of He Yue Industry, Lin Ching-an, and wife Hsiao Jin-dan typified the hands-on small business owners found in the town. They installed eight hosiery knitting machines in their traditional U-shaped courtyard home to do business with the world, and their products were shipped to markets as close as Japan and as far away as Alaska, the Middle East and the continental United States.

At one stage of Taiwan’s economic development, textiles accounted for one out of every three U.S. dollars of foreign exchange earned from exports. While high-tech products churned out from Taiwan’s science parks were big money earners, Taiwan’s economy was also being buttressed by knitting machines hidden in Taiwan’s rural townships that were run by husbands and wives day and night.

Earning NT$100,000 a Month

Lin and Hsiao, who are now semi-retired, got in the game when Taiwan’s economy was really taking off. At the peak of Taiwan’s hosiery industry in 1995, it exported US$200 million worth of products, and it was the leading exporter of socks to the United States in the early 1990s.

In those years, the hosiery industries in China and Southeast Asian countries were in their infancy, and Taiwanese suppliers received more orders than they could handle. A couple with a small factory in their home could clear hundreds of thousands of Taiwan dollars a month.

“Our machines would not stop running even during the Lunar New Year holiday. We would stockpile raw materials before the holiday. Every open space would be crammed with yarn,” Hsiao says, recalling the town’s golden era.

It was also in that era that Taiwan’s unique manufacturing structure, heavily reliant on small, household contractors took hold.

Producing a pair of socks requires a cumbersome process involving everything from designing the product, making samples and selecting and preparing the yarn, to knitting, sewing, setting and packaging. In other countries, single factories handle the entire process under one roof, but in Taiwan, small contractors handle each step in the process independently, a key factor in its competitiveness.

“Customization and mass production are generally seen as contradictory concepts. But with a large factory handling product design and taking orders and then farming the orders out to small operators, customized mass production becomes possible. That’s one of Taiwan’s unique advantages,” says Taiwan Hosiery Manufacturers’ Association Chairman Wei Ping-I.

Around 1995, however, large-scale factories in China began to sprout up, and Shetou gradually lost its luster. In 2005, Taiwan’s quota for textile exports to the United States came to an end, dealing a further blow to the community, and when the U.S. and South Korea signed a free-trade agreement in 2012, many described Shetou as a “dead town.”

New Life from Specialized Socks

Wondering if Shetou warranted the “dead town” moniker, we visited the township and found that it had not been extinguished but had withered to some extent. Small contractors struggled to survive, and those that remained had been forced to reinvent themselves. Some jumped on the exercise bandwagon, making running socks, while others focused on socks for medical use or even on the red-hot smart textile market.

Because of the early family-factory model, most factories in Shetou were scattered around fields rather than being planted in industrial parks, and even caused pollution.

The Shetou Hosiery Technology Park was later developed as the first industrial park in the area dedicated to the industry. Chiun Jiun Enterprise Co., housed in a four-story building clad in a marble exterior, was one of the first batch of companies to move in.

The company’s bright sample room with a shiny, polished marble floor is full of eye-catching items, from socks featuring the Hello Kitty, Gudetama, and Kumamoto bear (Kumamon) characters to functional jogging and baseball socks. Chiun Jiun avoids the high volume U.S. market, preferring to target Japan’s small-volume, high-quality market for limited edition products.

In 2017, Taiwan’s socks industry was down 40 percent from a year earlier, but Chiun Jiun’s sales were stable because of its market differentiation strategy, and the company even bucked the sector’s downward trend by expanding capacity.

Chiun Jiun Chairman Chen Ching-lin contends that Taiwan’s makers of socks became too dependent on America’s low-price market over the past 20 years, which gradually eroded their ability to design and develop new items. That deficiency has been especially telling at a time when the global market has trended toward distinct segments, he says.

China and South Korea have large-scale factories capable of producing large-volume, low-price orders, while Taiwan, known for its manufacturing flexibility and R&D prowess, specializes in orders involving high degrees of difficulty that others are unwilling to touch. Japan’s limited edition sock orders, requiring high quality and fancy styles, represent the type of orders China’s big factories are ill-suited to process.

According to Chen, a new Japanese sock design may undergo more than 30 changes from start to finish, and Japanese customers cannot accept defect rates of 0.01 percent (1 out of 10,000) on orders for 100,000 pairs of socks.

“Shipments to America can [have that defect rate], but it’s not acceptable in Japan,” Chen says.

Aside from quality, flexibility and speed are also paramount to survival. To meet the demands of Japanese customers, Chiun Jiun keeps a stock of 500 to 600 different-colored yarns at all times, and the boss himself adjusts machines as need be. That means Taiwan can deliver customized samples within 45 days, about half the time it takes Chinese manufacturers. (Read: Taiwanese Textile Industry's New Chance: Ethiopian Farmers + U.S. Machines)

Moving Up the Value Chain

Another company committed to this low-volume, multiple-item approach is one of Shetou’s leading lights, Six Companions Fabric Industry, maker of Queentex brand pantyhose, stockings, socks, and other hosiery products for such fashion brands as Victoria’s Secret, Vivienne Westwood and Chanel. Just as with Chiun Jiun, its business has remained strong despite the industry’s general downturn.

Wei Ping-I, who took over the family business in 1989 and now also heads the hosiery manufacturers association, says stockings made in Taiwan began to take off in the 1960s when it became good form for women entering the job market to wear them. But as women took to wearing sandals to work, single-color stockings fell out of favor.

In the 1980s, stockings emerged as a type of fashion, with fabrics displaying imitation diamonds or embroideries setting the trend. That led Six Companions to shift its approach from high-volume, single-color stockings to more upscale items.

Early on, Six Companions would easily sell 100,000 to 200,000 dozen stockings in a year. After it moved to the luxury end of the market, competing with Japanese and Italian brands, some items saw sales of only 500 dozen worldwide, but selling prices were 10-times higher than for single-color stockings.

The company targeted the United States market and spent 20 years cultivating distributors there. To keep them satisfied, it had to generate about 2,000 new items a year, far more than the 20 new products it would develop a year when it focused on mass producing inexpensive stockings. (Read: Ethiopia, Taiwanese Textile Industry’s New Paradise)

The Fastener Industry’s Cluster Effect

Kaohsiung in southern Taiwan offers another example of the hard-working spirit of Taiwan’s small-scale factories and the industrial clusters they have formed. Sanye Ward in Kaohsiung’s Gangshan District, is home to the densest concentration of fastener manufacturers in Taiwan, with more than 700 screw producers within a 5-kilometer radius. Screw exports earn more than NT$100 billion for Taiwan a year, supporting 30,000 jobs.

The area is peppered with corrugated-steel roof shops housing rows of machines spitting out screws at high speed, cutting, shaping and threading screws from coils of steel wire weighing two metric tons. The pinging sound of the screws being processed resembles that of loud pinball machines. Fasteners used in airplane engines or iPhones or as dental implants, or sold to Tesla, BMW, and IKEA, are all made in this inconspicuous “screw valley.”

Betty Chung (張雅欣), the vice president of one of the mainstays of the area, Anchor Fasteners Industrial, says local residents often joke that if you eat out at a restaurant in Gangshan, you are likely to run into an owner of a fastener factory.

What distinguishes the screw industry from others is the wide range of specifications that exist. The screws used for bumpers, chassis and shock absorbers may all be classified, for example, as automotive hardware, but they are significantly different from each other, a trait leading to the development of another unique industrial cluster.

Chung, who has management experience in both Vietnam and China, says that when Chinese screw manufacturers see a rival doing well, they focus on doing whatever it takes to steal away the competitor’s orders. But when Taiwanese companies get orders, they divide them among various producers that each specialize in a specific kind of product.

“Your company makes this, and another company makes something else. That ensures that the bosses of local screw factories never get into arguments,” says Metal Industries Research and Development Center analyst Kristy Chi.

The rise of Taiwan’s screw industry dates back to the 1970s, when the country’s major infrastructure boom led by the Ten Major Construction Projects created huge demand at home and China Steel Corporation, a key source of supply to the fastener industry, was founded in Kaohsiung.

The resulting “screw corridor” that emerged, stretching from China Steel in Xiaogang in southern Kaohsiung to Gangshan in northern Kaohsiung and Rende and Guiren in Tainan, helped propel Taiwan to become the world’s third largest producer of screws.

“Tooling factories also have a cluster in Kaohsiung, so they have quick access to raw materials and to annealing services. Everything is within 5 kilometers. That’s Gangshan’s biggest advantage,” says Fu Hui Screw Industry Chairman Tang Fu-jen.

The face of Taiwan’s screw industry has quietly changed, however, as the industry has come under pressure from China’s advances. (Read: The ‘Hidden Costs’ of ‘Hidden Champions’)

Selling Screws One by One

Anchor Fasteners is a good example. Its business has evolved from the days of selling a screw for NT$1, especially after it decided eight years ago to establish subsidiary Alliance Global Technology to move into the biomedical and medical supplies fields. In the new company’s facility, located in the Kaohsiung Science Park in Luzhu, there are no deafening noises from collisions between machines and metal or greasy floors spotted with lubricating oil.

Instead, one sees workers wearing isolation gowns and surgical caps testing metallic dental implants in a cleanroom. Screws are typically sold by weight, but these are sold by the unit, and those involved in their research and development are either professors or doctors at medical centers.

“It’s hard to start a business, but it’s even harder to keep it going,” says T.H. Chang, chairman of Anchor Fasteners and founder of Alliance Global Technology, explaining why he got into the biomedical field. His journey reflects the struggle and transformation of his industry.

Taiwan’s screw industry has no way to compete with China on volume, meaning it must target applications with higher technical thresholds for entry, such as in the automotive, rail transportation and aviation sectors. Companies able to produce these special screws with higher degrees of difficulty that China has yet to master can be found in Taiwan’s traditional “screw valley.”

For every 10 screws that Taiwan exports, nine are standard specification items that can be mass-produced and only one is a specialty product, but those who have the know-how to manufacture the more demanding screws can do very well.

Fu Hui Screw Industry makes fasteners for leading car brands such as Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Volvo and Land Rover, and its average selling price in 2018 of nearly US$5 per kilo significantly outpaced the industry’s average selling price of US$2.66 per kilo.

From Changhua to Kaohsiung, globalization has clearly wielded its immense clout, dominating Taiwan’s export-dependent economy, with the strong getter stronger and weak getting weaker. What has not changed is Taiwan’s agility and flexibility. For 30 years, these small and medium-sized enterprises hidden in the countryside have catapulted Taiwan into the international arena and continue to this day to help it shine.

Translated by Luke Sabatier

Edited by Tomas Lin

The original article is an extract from the following book, published by CommonWealth Magazine on Dec. 25, 2018. Find more excerpts in How Much Do the Taiwanese Love to Travel? The Wandering Youths of a Bygone Era and From Constitutional Reform to Democracy.