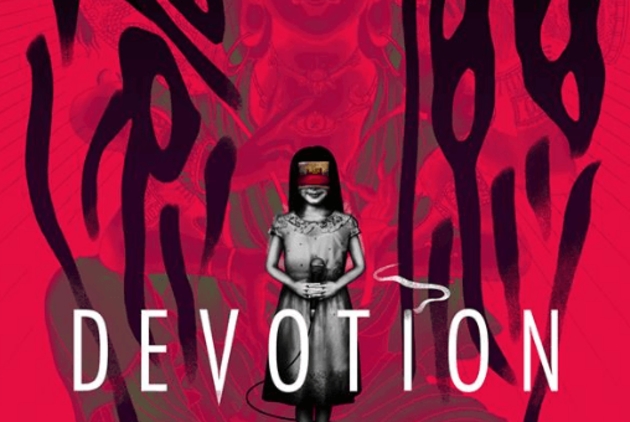

Red Candle Games

‘Devotion’ Gaming Controversy: Taiwan’s ‘Soft Power’ Meets China’s ‘Tough Power’

Source:Red Candle Games

Heated discussion has flared up on Internet forums across Taiwan and Hong Kong in recent days after an online game contained reference to the “Xi Jinping as Winnie the Pooh” meme.

Views

‘Devotion’ Gaming Controversy: Taiwan’s ‘Soft Power’ Meets China’s ‘Tough Power’

By Jeff Liu/A Crossing Reader's OpinionCrossing@CommonWealth

Following up on the success of its previous hit, Detention, Taiwanese gaming company Red Candle Games released Devotion, a new game containing a hidden “Easter egg” (which a subsequent company statement claims to be an oversight): a talisman used by a cult appears on the wall of one of the scenes in the game, affixed with a seal that says “Pooh Bear Xi Jinping.”

Once gamers caught on to the “Easter egg” hidden in the game, Devotion became the target of a boycott by Chinese players, attracting a torrent of negative reviews on streaming platform Steam, with many Chinese gamers who had purchased the game asking for refunds. Meanwhile, news coverage and discussions rapidly spread over the Internet. Responding to the incident, Red Candle Games issued an “Art Material Statement” claiming that the controversial content was “purely an accident” and that any harm or ill will caused was unintentional. The company has further issued a revised edition of the game, free of the controversial portion.

At the same time, Devotion’s Chinese distributor, Indievent, and Winking Entertainment, Red Candle’s agent for “overseas markets excluding China” as well as an investor in the Devotion project, each issued their own statements indicating that they had “terminated all cooperative relationships with Red Candle Games.” Winking Entertainment also added in its statement that it would seek damages from Red Candle for commercial losses incurred.

Red Candle Games’ six co-founders were listed on a follow-up statement explaining that “the words written on the art material do not represent Red Candle Games' stance, nor is it in any ways related to Devotion’s story and theme,” while apologizing to supporters including gamers and streamers and noting that Devotion had been removed from Steam across China.

Within just a short four or five days from word of the incident getting out, thousands of comments appeared practically instantly on Red Candle’s Facebook fan page and online forums of all popularity levels. The vast majority of commenters from Taiwan chalked up the controversial talisman to creative freedom, saying that “Chinese gamers are too easily triggered,” with some asserting that Red Candle had no need to issue a statement or apologize.

Meanwhile, Chinese gamers were vociferous in their criticism, calling it a “cheap shot” (“hiding political views within the game”), and saying things like “you (Red Candle Games) are making money from China, yet you still mock China with this lowbrow stunt.” Some online commenters threatened to boycott Red Candle, and even to extend the boycott to other Taiwanese gaming companies.

Thus, a hidden Easter egg in an online game became the fuse that ignited a war of words, venting years of pent-up ideological differences.

Instead of choosing sides and joining in the already overheated fray, I would rather refrain from commenting on who is in the wrong or in the right in this incident. I personally believe that the situation presents an opportunity for us to take another matter-of-fact look at “the peculiarity of the China market.”

Source: Red Candle Games’ Facebook Fan Page

Source: Red Candle Games’ Facebook Fan Page

Having established that creative freedom can come under the restrictions of “commercial contracts,” let us consider this incident (and many others like it) on another level, namely the “peculiarities” of the China market.

It is well known that, in the years since Xi Jinping took power, the Beijing government has only tightened its censorship of speech - even going so far as to “monitor the conduct” of foreign business people outside of China’s borders. From airlines registered in other countries being forced to use PRC-approved names for Taiwan flight routes lest they lose their authorization to fly in China, to a Marriott International Hotel employee liking a tweet by Friends of Tibet, arousing the ire of official Chinese media, which called for a boycott campaign and even leading police to open an investigation… we can clearly see that, in this “highly distinctive” market, it is impossible to keep politics and economics separate.

The Beijing government’s ideological interference in commercial activities has blurred the lines between the two via means such as official bans (direct revocation of business permits or forcing items off the market), official media condemnation, hacker attacks, mobilizing an Internet army to run resistance, or just letting the conditioning of Chinese consumers kick in and play out as their own resistance. All of these components make up the so-called “new normal” that foreign businesses (including those from Taiwan) from around the world face when they try to enter the Chinese market.

With the added dynamic of the growing trade war between the United States and China that is showing no signs of easing up, businesses or individuals looking to break into the Chinese market are confronted with a growing array of unpredictable risks.

And so the problem arises: Given the low degree of freedom and high degree of risk, why do so many Taiwanese business and individuals still have to tiptoe around when it comes to China?

In the case of Devotion, advance sales numbers in Taiwan far exceeded those in the China market before the controversy even erupted, and the game had been received with excellent ratings from players in Taiwan and around the world on various platforms. So why not just concentrate on the Taiwanese market, or for that matter the global market excluding China?

As for this point, generalizations are meaningless, as every business has a different strategy and market positioning. Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning two reasons in support of the idea of “business for business’ sake,” which essentially illustrate the realities confronting Taiwanese businesses today:

I. To pursue growth, companies must seek ever-larger markets.

Taking just the gaming industry as an example, according to statistics from gaming market survey company Newzoo, China’s gaming market was worth US$34 billion (in terms of total game industry revenue) in 2018 (around NT$1.06 trillion, ranking China first in the world ahead of the United States at US$31.5 billion. In comparison, Taiwan’s market was worth US$1.2 billion (around NT$36.9 billion) in the same year.

In other words, for a gaming company, the entire Taiwanese market is worth only around 3.5 percent of the Chinese market, thus such a sizable difference in scale makes it difficult to overlook the potential opportunities available across the strait. This is also why, even though everyone knows that in today’s China, with a “peculiar market” where the government’s attitude is “it’s my house; I make the rules,” countless Taiwanese- and foreign-invested businesses still choose to set up operations there.

Approvals are often beset with red tape; counterfeiting and copyright infringement is rampant, and unruly players and cheaters can diminish the gaming experience. While these impressions may have a basis in reality, they are not key factors for a gaming company considering whether or not to enter the Chinese market.

Running a business or one’s career is vastly different from engaging in ideological flame wars and looking for thrills online. Unlike such pursuits, it requires more rigorous and comprehensive analysis of such factors as market scope, competitors, and one’s relative advantages, future opportunities, and potential risks. Simply put, rational considerations more often than not outweigh emotional ones in order to lower the rate of failure.

Commercially speaking, I do not believe that the Chinese market is invariably every Taiwanese business’s only choice for broadening their reach. That said, I do recognize that given the vastness of the market, plus geographical, linguistic, and cultural traditions so close to Taiwan’s, it is still a top priority for many Taiwanese businesses under the current circumstances, despite the numerous risks.

II. The force of China’s “tough power” is tangible even for those not taking on the Chinese market.

After the Devotion incident, Red Candle’s agent for overseas markets excluding China, also a cooperative vendor and investor in the gaming project, quickly severed all cooperation links with Red Candle, even announcing that it would sue for damages. In light of this case, we can clearly identify the following 10 cruel realities:

Taiwanese businesses venturing out into the world to expand their market, even if China is not their target market, can still bear the brunt of China’s “tough power.”

Put in the most direct and understandable terms, “tough power” is akin to the way classmates would say, “if you’re friends with him, I won’t be friends with you.”

That is to say, if a foreign-invested business sets up operations and invests in China (similar to Winking Entertainment in this case), or has dealings with a Chinese state-run enterprise (or certain private enterprises), all it takes for that enterprise is to do something Beijing deems offensive to China’s “Thin Red Line,” and, regardless of where the alleged “offense” transpires, the business could face repercussions - from international airlines forced to “correct” Taiwan’s name, to a Japanese apparel brand forced to “clarify its position” in a conflict between Japan and China.

Accordingly, whether deliberate or unintentional, if a corporation or its employee crosses the line set by Beijing, even if that company does not have direct investments and dealings with China, it runs the risk of unexpected losses stemming from losing cooperative partners under pressure from Chinese government authorities. As time goes on, both enterprises and individuals catch on to the concept of self-censorship and avoid sensitive content without prompting, or disavow relations with any corporation or individual that might come in conflict with Beijing.

This is not a normal state of affairs for corporate relations, yet it is the daily status quo both inside and outside of China.

Criticism of such enterprises caving into Beijing’s pressure for being spineless or having no national loyalty is certainly valid. But the reality is that company management needs to answer to the board, and keep the business running. So after weighing all options, more often than not they make the decision to backpedal, as in the example described above.

How can one still make money while “standing up”?

I am sure that the two aforementioned points generally illustrate the realities on the ground for businesses in Taiwan as well as around the world: The China market covers a huge scope, offering attractive growth opportunities; however, at the same time, it is also becoming increasingly unpredictable, and it is impossible to directly translate such standards as “free trade” and the “free market” practiced for ages in advanced Western economies.

Accordingly, no matter your national allegiance or ideology, if you want to survive in the current business world, you need to be more rational, and come up with strategies for dealing with China.

Taking the examples of Taiwanese businesses that have made the jump across the Taiwan Strait: While some have opted to cozy up to the Beijing regime, others opt to skirt the boundaries of the ground rules, leveraging the alluring culture and exquisite design fostered by Taiwan’s diverse values and cultural fusion without triggering Beijing’s sensitivities (i.e. directly promoting Taiwanese, Tibetan, or Xinjiang independence, or insulting government leaders) to successfully capture the Chinese market, and subtly influence consumers.

Naturally, we could completely ignore the Chinese market, or even go so far as refuse to have any sort of dealings with Chinese-funded businesses. However, we must acknowledge the reality of China’s “external tough power” and the limited nature of Taiwan’s domestic market, while being extra mindful of our choices in partners as we make efforts to expand our market.

As a Taiwanese person, I am sure that most of us in this generation are accustomed to the environment our democratic forefathers fought for and earned, including freedom of speech, democratic elections, and open debate.

Nevertheless, we must be aware that, in a fickle international political and economic climate, with a superpower neighbor breathing down our necks, preserving rights and privileges that can seem obvious requires the “power” of the entire country’s society, whether in terms of economic, diplomatic, or national defense, to sustain it.

It is my sincere hope that, regardless of party affiliation, government officials and legislators can better familiarize themselves with the international facts on the ground, as well as tangible strategies for Taiwan’s economic and industrial development, rather than simply uttering empty slogans or even exploiting ideological antagonism inside Taiwan.

They should expend greater effort to assist competitive, creative Taiwanese enterprises to expand their markets, and forge greater “soft power” influence. This, I believe, is the only way to maintain Taiwanese values in the face of China’s “tough power.”

Translated by David Toman

Edited by Sharon Tseng

Crossing features more than 200 (still increasing) Taiwanese new generation from over 110 cities around the globe. They have no fancy rhetoric and sophisticated knowledge, just genuine views and sincere narratives. They are simply our friends who happen to stay abroad, generously and naturally sharing their stories, experience and perspectives. See also Crossing Arab World.

Original content can be found at the website of Crossing: 赤燭遊戲《還願》風波:當台灣「軟實力」再次對上中國「鋭實力」

This article is reproduced under the permission of Crossing. It presents the opinion or perspective of the original author / organization, which does not represent the standpoint of CommonWealth magazine.