Higher Productivity ≠ Higher Pay

The Forces behind Taiwan’s Stagnant Wages

Source:Kuo-Tai Liu

Taiwan’s changing industrial structure has resulted in large-sized companies dominating exports, pushing aside the small and medium-sized companies that were once the country’s backbone. Amid that transition, workers’ real earnings have remained relatively stagnant, unable to keep pace with economic growth. Why is that and what can be done?

Views

The Forces behind Taiwan’s Stagnant Wages

By Elaine HuangFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 689 )

Taiwan’s economy was long carried on the back of its small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Small business owners traveled the world, a briefcase in hand, to snag orders and were major contributors to the international trade and economic development that became Taiwan’s lifeline.

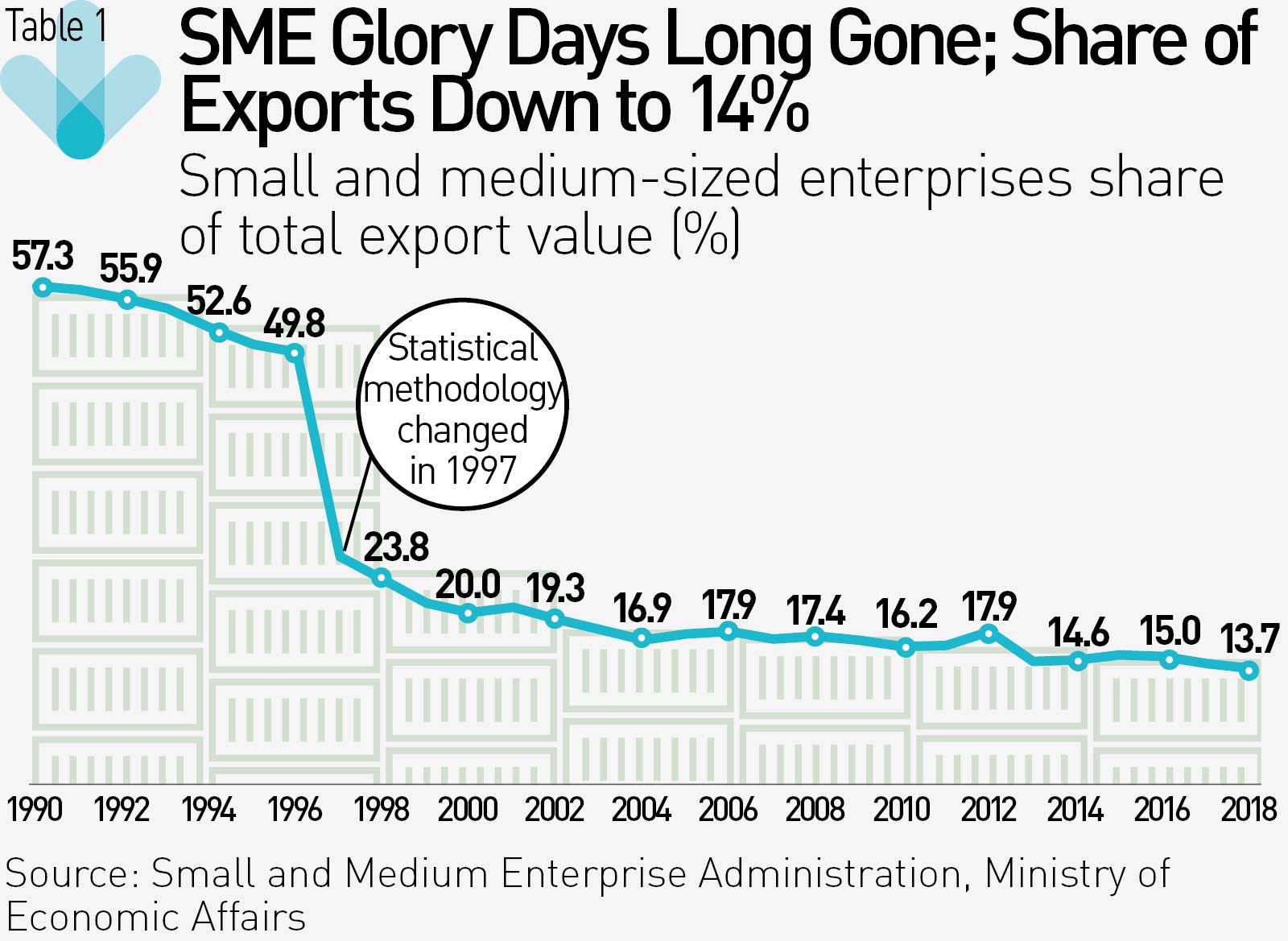

But SMEs, which account for 97 percent of all Taiwanese companies, have seen their share of the country’s exports plunge from more than 60 percent in the 1980s to 13.7 percent in 2018. (Table 1)

SMEs: Declining Share of Exports

This reversal in fortune for SMEs reflects the changing face of Taiwanese companies and the transformation of the country’s industrial structure. A key driving force of the transition has been the growing importance of financial markets, which have enabled companies to raise funds in capital markets, helping SMEs gradually get bigger.

“It used to be that a company with capital of NT$800 million was considered big. Now, [companies with] NT$1 billion [in capital] do not seem very big because companies have all grown in size,” says CTBC Financial Management College professor Shih Kuang-hsun.

Amid the changing nature of local companies, which ones have been rapidly expanding in size? Electrical equipment and parts became an important export category at the end of the 1990s, and accounted for more than 30 percent of all of Taiwan’s exports by 2003 and 43 percent of total exports in 2018.

The first generation of the information and communications industry, which relied on manufacturing and exporting, also helped companies get bigger. Enterprises relied on leveraging the fertile soil for these “intermediate goods” to inject additional vitality into Taiwan’s economic expansion.

“Without these so-called intermediate goods you cannot connect to raw materials upstream or markets downstream,” Shih says.

The commercial model enabling contract manufacturers to make money on these intermediate goods helped them grow in size, but it also imposed serious constraints on the value-added of the products Taiwanese companies pumped out.

Wages: Not Helped by Higher Productivity, Growth

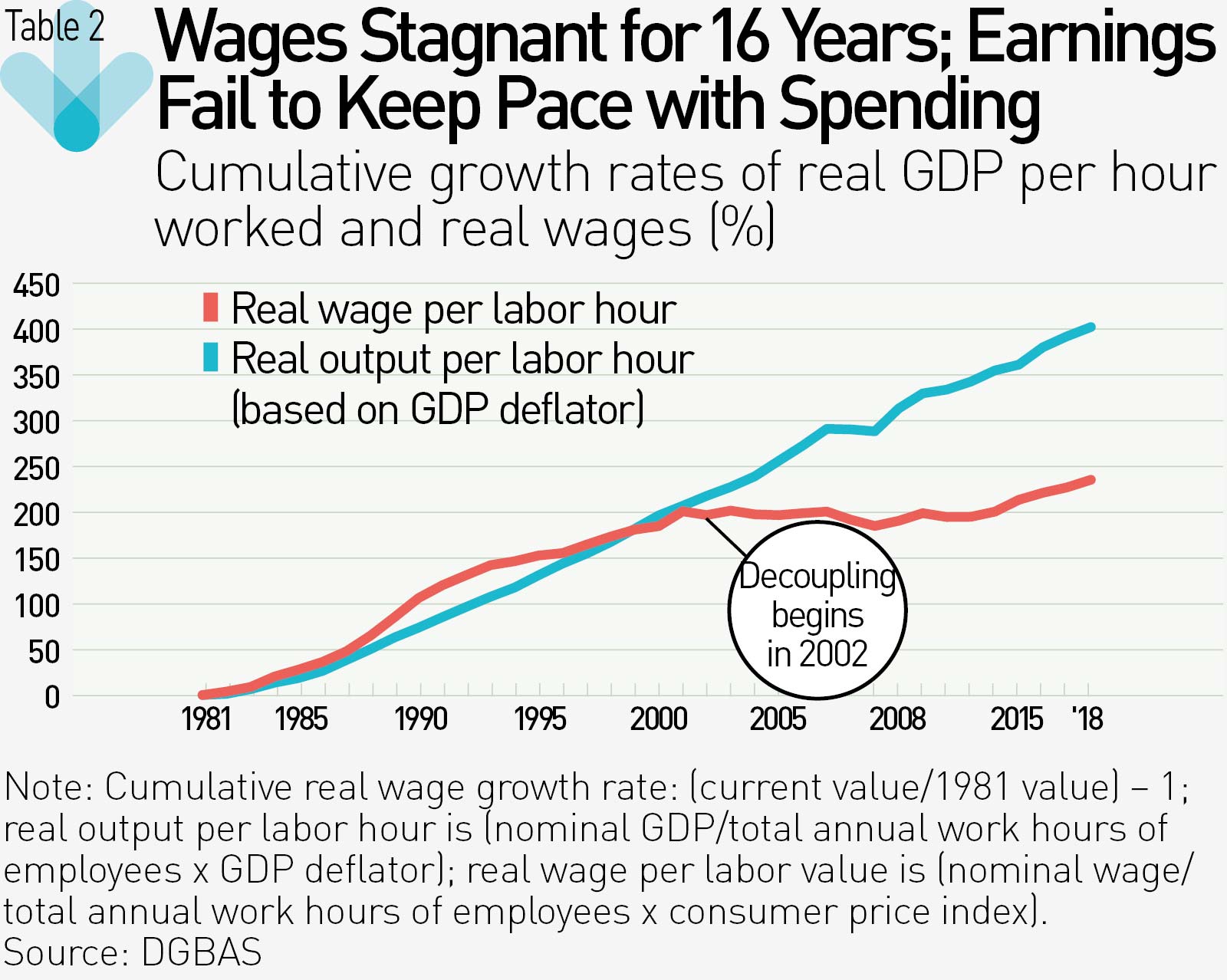

A casualty of the trend has been the alarming lack of correlation between productivity growth and wage growth.

In theory, gross domestic product (GDP) growth represents gains in productivity and the economy and should propel wage growth.

The theory prevailed in practice in Taiwan up to around 2002, but less so since then. Real GDP, a key barometer of worker productivity, has continued to grow, but real wages, which represent a worker’s spending power, have remained relatively stagnant for 16 years. (Table 2)

Yang Tzu-ting, an assistant research fellow with the Institute of Economics at Academia Sinica, explains that the stagnation is the result of two forces. The GDP deflator, a measure of the prices of goods produced, has been declining steadily, while the consumer price index, which measures changes in the prices of consumer goods, has been moving higher. The widening gap between the two indicates that while Taiwan’s productivity has been on the upswing over the past 16 years, the products it is producing are getting cheaper.

So why did the trend toward lower prices and lower margins become more noticeable after 2002?

“You can’t overlook the rise of China,” Yang observes. China was admitted to the World Trade Organization in 2001, and the preferential tariff treatment it received turned it into the world’s factory. The information communications supply chain, including Taiwanese contract manufacturers, moved West to take advantage of China’s cheap labor to grow. While that drove China’s rise, it also inhibited the technology upgrades and salary increases Taiwanese companies at home needed to make.

In effect, China moved into Taiwan’s bailiwick, the contract manufacturing field, and created a “red ocean” of low-price competition, pushing down the prices of Taiwanese exports over the long term. Yet productivity has risen since then, indicating that its benefits have been diverted toward producing increasingly cheaper products rather than boosting wages.

That reflects the bottleneck Taiwan industries have faced in re-engineering themselves over the past 20 years of stagnant wages.

But the U.S.-China trade war has brought Taiwan a new opportunity over the past year, generating increased investment and offering hope that Taiwan’s economic structure can improve as companies look to diversify away from China.

In the fourth quarter of 2019, Taiwan’s economic outlook took a turn for the better as Taiwanese companies searched for land and recruited talent to increase their capacity, and overseas giants such as Google, Microsoft and Amazon came to Taiwan to set up R&D centers.

“In the past they saw Taiwan as a factory. Now, they see it as an R&D center. To Taiwan, that is a type of value-added,” observes Lien Hsien-ming, the director of the Taiwan Studies Center at National Chengchi University (NCCU).

Academia Sinica’s Yang adds: “Over the past 20 years, everybody skipped over Taiwan to invest directly in China but now they are thinking about Taiwan. Investment echoes the future and can drive wage growth.”

Though the real earnings of Taiwanese workers have stayed relatively flat, the good news is that the unemployment rate and total work hours have gradually improved.

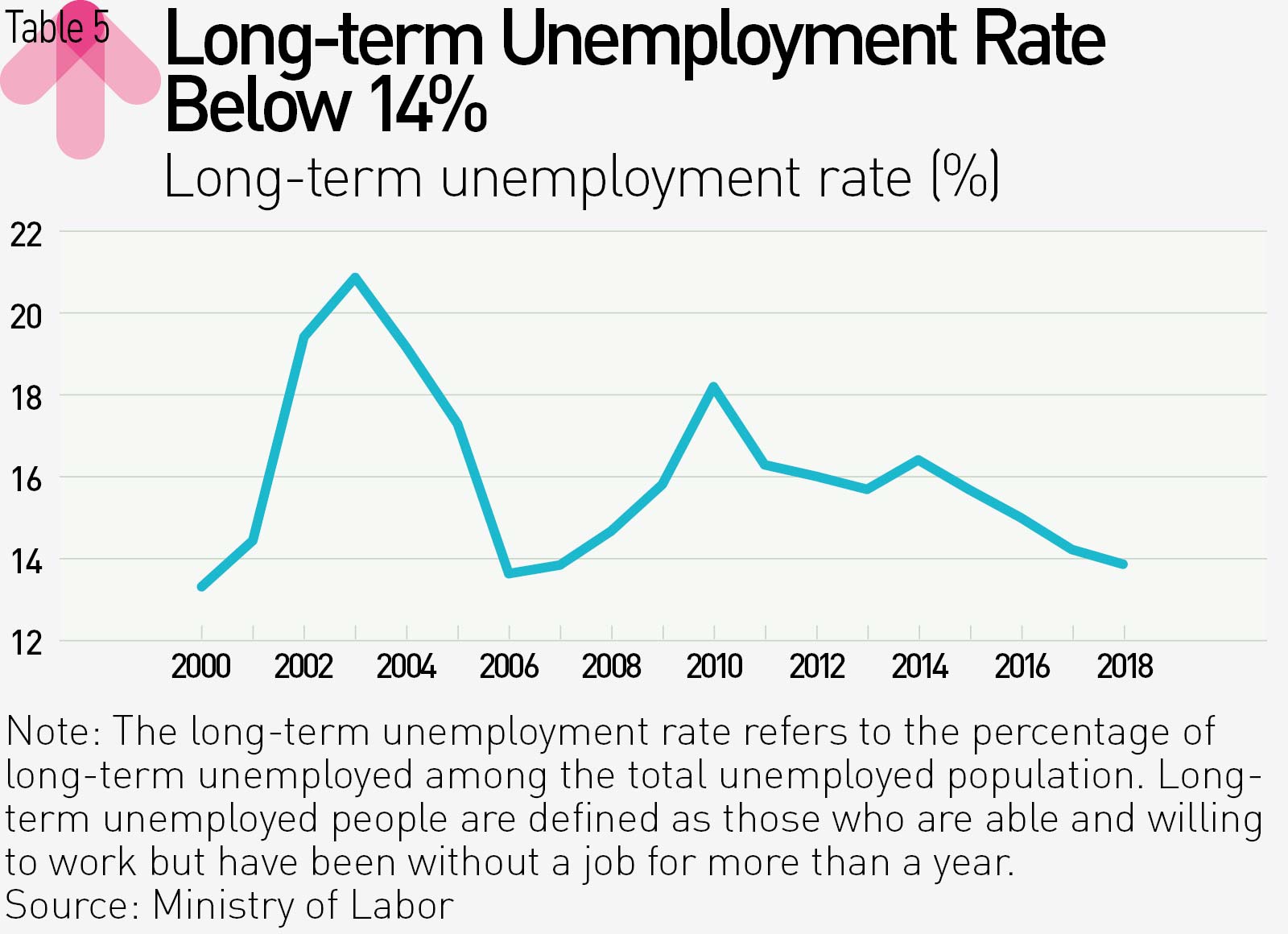

Labor: Long-term Unemployment, Overwork on the Decline

Taiwan’s jobless rate has fallen from 5.9 percent during the global financial crisis in 2009 to 3.7 percent in 2018, and the long-term unemployment rate has gone from 20.9 percent in 2003 to 13.9 percent. The two indicators are at their lowest points in nearly 10 years. (Table 5)

Compared to unemployment in OECD countries, Taiwan’s 3-percent plus jobless rate is relatively good,” NCCU’s Lien says.

Worth noting, however, is rising unemployment among younger Taiwanese. Among those aged 15 to 24, mid- and long-term joblessness as a share of total unemployment continues to rise, according to the manpower utilization survey put out by the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics. So while overall long-term unemployment is on the decline, it looms as a potential fault line for younger Taiwanese.

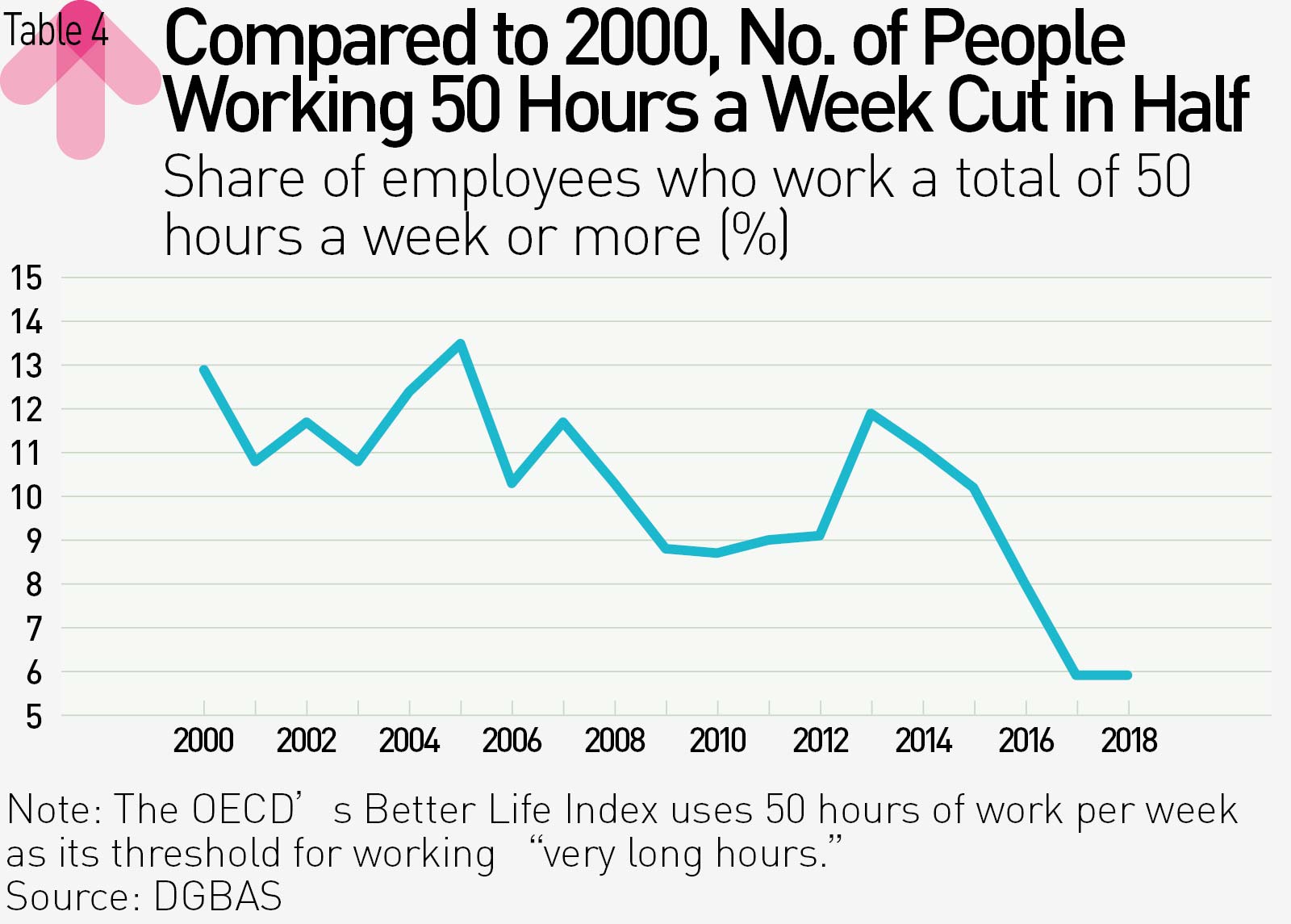

In terms of total hours worked, the overwork syndrome that plagued Taiwanese workers in the past has shown some improvement, slightly easing Taiwan’s notorious reputation as the “island of overwork.”

The OECD’s “Better Life Index” uses 50 hours of work per week as its threshold for working “very long hours.” In Taiwan, the percentage of workers toiling an average of more than 50 hours per week has fallen steadily from 12.9 percent in 2000 to 5.9 percent in 2018. (Table 4) The decline coincides with two revisions to the Labor Standards Act, the first one in 2000 cutting maximum work hours to 84 hours every two weeks and the second one in 2017 instituting a 40-hour work week.

Compared to other countries, the 8 percent of workers who regularly worked more than 50 hours per week in Taiwan in 2016 was well below the 21.8 percent seen in Japan and the 20.8 percent seen in South Korea.

For the metric “usual hours worked per week by the full-time employed,” Taiwan’s 42.3 hours in 2017 came in below Japan’s 45.1 hours, South Korea’s 46.8 hours and Singapore’s 45.9 hours.

When the 40-hour work week rules were first passed in 2017, the Ministry of Labor and local labor bureaus promised it would protect workers’ rights and interests. (Photo by Chien-Ying Chiu/CW)

When the 40-hour work week rules were first passed in 2017, the Ministry of Labor and local labor bureaus promised it would protect workers’ rights and interests. (Photo by Chien-Ying Chiu/CW)

The revisions to the Labor Standards Act turned out to be a mixed bag for workers, however, depending on their professions and work environments.

NCCU’s Lien contends that while work hours in Taiwan are shorter than in Japan and South Korea, Taiwan’s Labor Standards Act is based on a factory work model that existed 20 years ago.

“The nature of work is constantly changing. Twenty years ago there was no such thing as Uber Eats,” he says, arguing that those types of part-time, gig economy jobs will have to be accounted for in regulations in the future.

Despite recent revisions, the Labor Standards Act remains based on the factory-driven economy of 20 years ago. It will likely have to be revised again in the future as work patterns change. (Photo by Ming-Tang Huang/CW)

Despite recent revisions, the Labor Standards Act remains based on the factory-driven economy of 20 years ago. It will likely have to be revised again in the future as work patterns change. (Photo by Ming-Tang Huang/CW)

Finance: Government Debt Ratio Has Risen, But Under Control

Still, to upgrade Taiwan’s overall industrial structure and environment, sound government finances are a necessity.

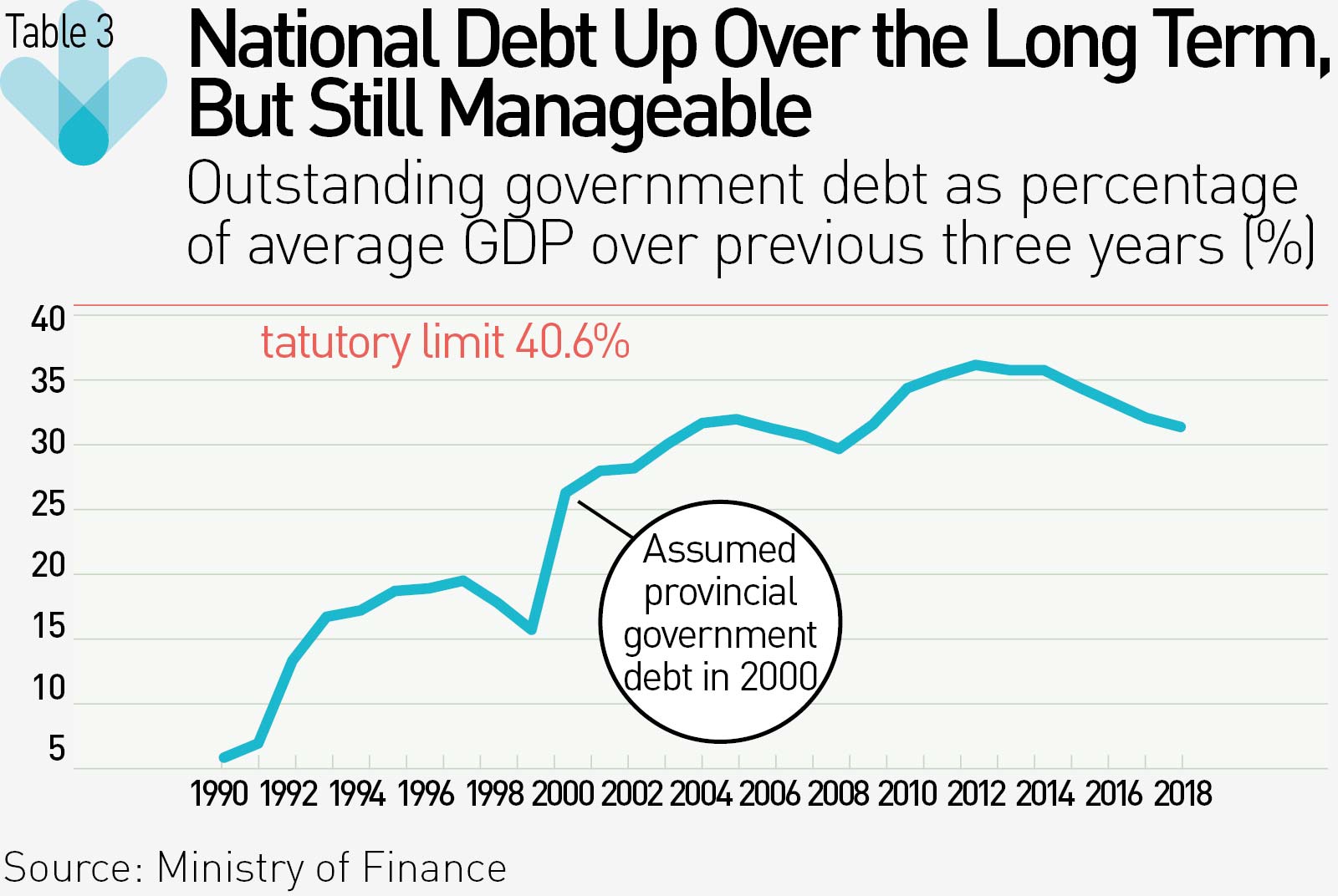

In terms of government debt, the central government’s debt ratio (government debt as a percentage of GDP) hit a high of 36.2 percent in 2012 to 31.4 percent in 2018, but it still remains close to the statutory limit of 40.6 percent and is nearly double what it was 20 years ago. (Table 3)

In 1998, Taiwan adopted what become known as the “integrated income tax system” to eliminate double taxation on dividend income from stocks and business profits. The new system in effect lowered tax burdens on dividend income and offered a new form of preferential tax treatment, leading to considerably lower tax revenues. In the years after that, the government lowered corporate income tax rates, inheritance tax rates and gift tax rates, further eroding tax receipts and widening budget deficits. The situation only improved after 2014 as solutions were put in place to strengthen the government’s finances and subsidy and pension systems were re-assessed.

Yet while Taiwan’s debt ratio is much higher than it was 20 years ago, it remains relatively low by international standards.

Taiwan’s government debt also differs structurally from that of other countries because none of it is foreign debt; it is all national debt. Taiwan boasts such robust foreign exchange reserves that it can even lend money to other countries, and its lack of foreign debt helped it withstand the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis without too much upheaval. In contrast, South Korea, which had a sizable foreign debt, was hard hit by the crisis.

To ease the adverse effect of the 2008 global financial crisis on domestic consumption, Taiwan’s government issued consumption vouchers worth NT$3,600 to each resident, running up a debt of NT$85.8 billion. (Photo by Ming-Tang Huang/CW)

To ease the adverse effect of the 2008 global financial crisis on domestic consumption, Taiwan’s government issued consumption vouchers worth NT$3,600 to each resident, running up a debt of NT$85.8 billion. (Photo by Ming-Tang Huang/CW)

“Among Asian countries, Taiwan is pretty much a model student,” says Wu Wen-chieh, an associate professor in NCCU’s Department of Finance.

A country still needs debt to develop, however. The United States government has a debt ratio of about 105 percent at present, while Japan’s was 238 percent in 2018 and Singapore’s was about 111 percent in 2018. In Singapore’s case, it has used debt to stimulate the country’s economic development.

Wu said Taiwan’s debt was still within a reasonable range even if its debt ratio does not include hidden liabilities, such as future pension obligations. But he cautioned that a balance needed to be struck between fiscal discipline and economic stimulus.

“If the people insist that the government maintains a low debt level and does not collect taxes or raise tax rates, the government will have a hard time doing things or improving public infrastructure,” contends Wu, who believes that while remaining financially disciplined is important, the country’s continued economic development must also be accounted for.

CTBC Financial Management College’s Shih concurs. “Taiwan’s economy has just about reached a critical juncture. The people now care about economic development that gives them a sense of well-being,” he says.

In looking ahead to the next 20 years, Taiwan’s economic development has reached a new inflection point: an export-oriented island economy driven primarily by its biggest companies is now looking toward new investment and new projects and higher value-added goods to break the stranglehold of stagnant wages over the past two decades.

Have you read?

♦ Are You Making More than the Average Taiwanese?

♦ Taiwan’s Sluggish Minimum Wage Growth Has Fallen Behind Its Contemporaries

♦ No Longer an Asian Tiger?

Taiwan Milestones

Key Economic and Labor Milestones

1996 The Public Debt Act is passed, lowering the ratio of public expenditures to GDP and lowering budget deficits.

2000 The central government’s debt soars as it takes on the debt of the provincial government after that body was dramatically downsized in 1998.

2001 Maximum working hours are lowered from 48 hours (a six-day work week) to 84 hours every two weeks.

2007 The minimum wage is increased for the first time since 1997, from NT$15,840 per month to NT$17,280.

2009 To cope with the global financial crisis, the government issues a consumption voucher of NT$3,600 to all Taiwanese residents, adding debts of NT$85.8 billion.

2009 To boost youth employment, the Education Ministry introduces an internship program to get college graduates into the workplace. It is introduced in two stages from April 2009 to September 2011. The students are paid NT$22,000 a month.

2014 An initiative to solidify government finances is launched.

2017 The 40-hour work week is instituted through a revision of the Labor Standards Act.

Translated by Luke Sabatier

Edited by Sharon Tseng