Gogoro’s EV Dream Facing Major Headwinds

Source:Kuo-Tai Liu

Taiwanese electric scooter powerhouse Gogoro has talked of overseas expansion for years, but those plans have been put on hold. As it looks to deepen its presence in Taiwan, what other obstacles is it facing and how serious are they?

Views

Gogoro’s EV Dream Facing Major Headwinds

By Ching Fang WuFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 702 )

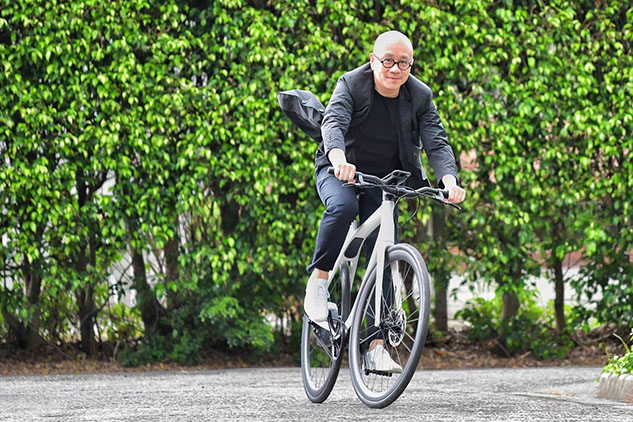

“You can’t be too worried about making it abroad. You have to first see if you’re ready,” said Gogoro CEO Horace Luke in discussing his overseas expansion plans while sitting next to his company’s newly unveiled “Eeyo” Smartwheel electric bicycle.

That attitude was a major departure from his ambitious stance of recent years. “I only have one chance, and we’re not yet ready,” he said.

Can Taiwan Spawn a Startup Unicorn?

Gogoro was once touted by the National Development Council, Taiwan’s top economic policy planning body, as one of two Taiwanese companies capable of emerging as unicorns – startups that develop a net worth of over US$1 billion. Thus, the Gogoro CEO’s change of heart not only has implications for his company’s fate but also for the possibility of Taiwan’s “startup dream” becoming a reality.

Established nine years ago, Gogoro announced its presence at the Las Vegas Consumer Electronics Show with a made in Taiwan electric motorbike and then quickly surged to the top of the domestic market as Taiwan’s top electric scooter brand.

The company eventually set the standard for electric scooters in Taiwan, built a support base of 300,000 fans, and carved out a 10 percent market share for newly sold motorbikes. This meteoric rise gave the startup equal status with the big manufacturers of gas-powered two-wheelers.

Financing Luke’s dream were a number of major investors, including the National Development Fund, Ruentex Group Chairman Samuel Yin, Panasonic of Japan, and Temasek Holdings, which is owned by the Singaporean government.

Even overseas, Gogoro and Luke got off to a smashing start. He set up Coup Mobility, a Berlin-based electric scooter sharing service, with German auto parts manufacturer Bosch in 2016 that put 5,000 Gogoro bikes in Berlin, Paris and Madrid.

Selling motorbikes, however, was simply a way to enter the market. Luke’s bigger ambition was to forge an energy trading platform, and if he were to succeed it would be the first time Taiwan was actually at the forefront of setting a standard for an industry.

Gogoro, in fact, did establish a standard for electric motorbikes in Taiwan. Motorbike manufacturers Yamaha Motor, Tailing Motor (Suzuki), Aeon Motor, and PGO Scooter all joined Gogoro’s technical services platform – the Powered by Gogoro Network (PBGN) alliance – and developed GoShare ride sharing services.

“Our company is already a conglomerate,” Luke said.

Major headwinds began blunting the company’s seemingly inexorable advance for the first time, however, over the past year. In November 2019, Coup announced it was shutting down its scooter sharing service, and then Gogoro encountered resistance and stagnation in Vietnam, a market it had eagerly targeted.

Even a long-planned gambit to team up with Southeast Asia’s biggest ride-hailing service provider, Grab, fell through when competitor Kwang Yang Motor (KYMCO) used a US$30 million investment in Grab in February 2020 to get its business for scooters and the battery charging system.

The company’s difficulties can be summarized by three major headwinds challenging its market position.

First Big Challenge: Overseas Resistance

MIT Runs into Vietnamese Nationalism

When Bosch shut down Coup late last year, it attributed the move to high costs and fierce competition. In fact, however, Gogoro’s electric scooters were never a great match for conditions in Europe.

Weather was one major obstacle. Motorbikes are rarely used during the frigid winter months. The lack of basic infrastructure also hurt the service. Coup once explained on Twitter that it could not sell its old electric scooters on the secondhand market because Europe does not have the charging infrastructure like Taiwan does.

Gogoro also considered entering the Vietnamese market as a Taiwanese electric scooter brand, but after evaluating the market for a year, it halted its plans at the end of last year. Vietnam is the world’s fourth largest motorbike market, with one of about every two Vietnamese owning a motorized two-wheeler. Nearly 9,000 motorbikes are sold a day, about 3.6 times as many as in Taiwan, and the market has steadily grown 3-5 percent a year.

More importantly, Vietnam’s electric scooter market is poised to explode. To ease air pollution in their cities, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City announced bans on fuel-powered motorbikes entering their downtown areas starting in 2025.

So why would Gogoro’s Vietnam ambitions come to a screeching halt?

“In Vietnam, motorbikes involve nationalism. The government wants its vehicles made at home,” said Peter Wu (吳明穎), general director of Sheng Bang Metal Co. in Vietnam and the head of the Dong Nai branch of the Council of Taiwanese Chambers of Commerce in Vietnam.

Foreign vehicle makers looking to grab a foothold in the Vietnamese market have to build good relationships with the government and spend a lot of time forging a local supply chain, Wu said.

One industry insider suggested Gogoro would have to find a local battery manufacturer and produce core technologies such as motors there. If made in Taiwan, the scooters would face an additional import duty, and building a battery-sharing network would require the cooperation of local governments.

“Unless you set up an R&D team locally or discuss a services partnership with a big business group like Vingroup, it will be really hard to gain a presence in Vietnam,” the industry insider argued.

Vingroup is a major Vietnamese conglomerate that got its beginnings in real estate development. Last year, automotive subsidiary Vinfast rolled out a new electric motorbike priced at around NT$40,000 to NT$50,000.

When Luke was asked why he had put Gogoro’s overseas expansion plans on hold, the word he used repeatedly was “ready.”

“Our technology is ‘ready’ and our backend system is almost ready. Our portfolio is almost full….but ultimately it is very important for our partners to be ready…..I want to give our partners the chance to prepare their products. Every company has many different types of vehicles, and we can only succeed if we go abroad together and become a platform. We need to create a ‘Team Taiwan,’” Luke said, referring to his PBGN alliance.

He may not have answered the question directly, but his strategic direction could not have been clearer – this potential unicorn wants to concentrate for now on its home market.

“Lyft was a unicorn and only operates in the U.S. market. Grab’s main market is Southeast Asia,” Luke said in making the point that unicorns did not need to move aggressively into overseas markets. Though Taiwan’s population is only around 23 million, it still offers plenty of opportunity.

“Taiwan’s market is very mature. Almost every person has their own motorbike, and so it’s the ideal place for testing and developing innovative ideas,” Luke said.

In other words, the key to Gogoro’s growth, at least in the next few years, will be the rate at which its smartscooters replace the 5 million old motorbikes sitting in Taiwan’s streets and alleyways.

But the company’s current sales indicate that grabbing a share of the replacement market may be more difficult than anticipated.

Second Big Challenge: Falling Fuel Prices/Subsidies

Gogoro Year-on-year Sales Down 34%

In the first five months of 2020, the number of new licenses issued for Gogoro vehicles (the way sales volume is calculated in Taiwan), fell 34 percent from a year earlier. In contrast, the sales of fuel-powered motorbike makers KYMCO, Sanyang and Yamaha were all up slightly from a year earlier.

Falling fuel prices, which have eroded the incentive to buy an electric motorbike, explain part of the downturn, but the most direct blow was the narrowing gap in subsidies for buying new fuel-powered and electric scooters.

To accelerate the retirement of old motorbikes, the Environmental Protection Administration decided to provide a NT$5,000 subsidy for purchases of both 7th-stage emission standard fuel-powered motorbikes (the toughest emission standard, similar to Euro 5) and electric two-wheelers. At the same time, special subsidies for electric vehicles from the Industrial Development Bureau and local governments have been lowered. So even though Gogoro has promoted a more affordable model to drive sales, its fortunes still have taken a turn for the worse as the financial incentives for buying one its vehicles weaken.

“I know the government is facing certain pressures. Maybe the transition (to electric vehicles) has been too fast, but you have to provide the right incentives at the right time,” Luke said, hoping that the subsidies could be extended to 2024 to give his alliance partners and supply chain time to grow.

“All of the major global motorbike manufacturers are Japanese brands. If we don’t go electric, what would Taiwan’s future look like?

Gas-powered scooters are back on the ascent, and several observers see this year’s sales numbers as evidence that without subsidies, Gogoro will have a tough go carving out a share of the 5 million motorbike replacement market.

Third Big Challenge: Backend Management

Repair/Maintenance Issues Upset Gogoro Diehards

The final major challenge is people, starting with retaining talent.

The head of the power system department who developed Gogoro’s core technologies and its energy systems engineering chief both left the company earlier this year. Though Luke stressed it was perfectly normal for people to come and go, the moves may affect the company’s R&D competitiveness.

At the same time, signs of unease are appearing among Gogoro diehards who have sent the company’s fortunes soaring, bringing a degree of uncertainty to its future sales.

It took Gogoro only four years to become Taiwan’s fourth biggest motorbike maker. Its next step will have major implications for the future of the market.

Electric and fuel-powered motorbikes are such completely different machines that traditional repair shops cannot handle Gogoro’s smartscooters, forcing users to wait patiently for official Gogoro repair and maintenance services.

Though Gogoro has worked hard to train technicians at cooperating repair shops and promised to add 30 service centers this year, backend service capacity remains inadequate for the growing demand. Some Gogoro backers have even complained of having to wait a month for spare parts.

Those issues and a dispute over the use of unlimited battery use rates by food delivery people have exacerbated the dissatisfaction of Gogoro users, calling into question whether the company can continue to count on its once loyal social community in the future.

Gogoro responded that appointments for repairs or basic maintenance average waiting times of under eight days for all of Taiwan and around 18 days in Taipei.

“Gogoro can be seen as a success, but it still has huge room for growth in Taiwan’s market,” said Chiu Yi-chia, vice dean of National Cheng Chi University’s College of Commerce. Gogoro still has not developed a clear strategy to engage in the mainstream user market, he suggested.

In its initial phase of operations, Gogoro has conquered young consumers who are early adopters and gravitate to new technologies, Chiu said, “but after getting through this niche market, many startups are unable to take the next step into the mainstream and fade away.” That’s because early adopters and techies represent only a small minority of consumers, and a sizable gap still exists between this segment and the mainstream market.

For innovative products to gain larger followings and go more mainstream, Chiu argued, they must overcome two challenges – they have to price their products more competitively and they must evolve into a platform and nurture an ecosystem. “Facebook, for example, went from being an address book to a social ecosystem through which it works with advertisers, companies and software developers.”

As long as a platform lacks maturity, it will lack the competitiveness needed to expand into international markets. “Gogoro’s ecosystem has yet to come together. But it’s not something that will happen in a single bound. It has to be slowly built up,” Chiu said.

Whether or not Gogoro can overcome the many headwinds it faces to emerge as a unicorn will not only determine the company’s future but also be eagerly watched in Taiwan’s startup circles, who are eager to find models of success.

Have you read?

♦ Retaliatory Consumption is Here! As Lockdowns Ease, This MIT Product is Spinning Away

♦ Over 10K Shared e-Scooters: Why Is Japan Seeking Knowhow from Taiwan?

♦ COVID-19: How Taiwanese companies are rethinking 2020

Translated by Luke Sabatier

Uploaded by Judy Lu