When the One in the Dark Speaks, Will You Listen?

Source:Joe Henley

Sometimes, the question of whether you could do something is really whether or not you should. I knew I could write a book about the hardships faced by Taiwan’s community of Southeast Asian migrant fisherman, caregivers, and factory workers. I had the material. I’d done the research. I’d put the years in. But I’m not part of that community, either ethnically or economically. So, should I? The road to finding the answer was neither easy nor straightforward.

Views

When the One in the Dark Speaks, Will You Listen?

By Joe Henleyweb only

It started at the beginning of 2015. On a gray Sunday morning, I headed to Taipei Main Station. A Filipino woman, Jasmine, had summoned me there. She had found my name in the pages of the Taipei Times, where I had a weekly music column. She wanted to talk to me, but it had nothing to do with music. Rather, the topic of conversation was to be something far more serious.

Photo provided by Lennon Wong, Chairman of the SPA

In the central hall of Main Station that Sunday, I was met not only by Jasmine, but by a group of more than a dozen women, all hailing from the Philippines. One by one they shared their harrowing stories with me—stories of sexual harassment, economic extortion, manipulation, and fraud, all experienced during the course of their work as in-home caregivers in cities from north to south, east to west, throughout Taiwan.

To a woman, they had all been exploited in one way or another; in many cases in multiple, terrible ways. But also to a woman they were determined. They would not allow themselves to be victimized. They would fight back against a system designed to keep them down, out of sight and out of mind, marginalized in ways that, were they Taiwanese or members of Taiwan’s Western expatriate community, a rallying cry for equality and justice would have been raised long ago.

More than once, I was moved to tears by their stories. Over the next few years, I wrote about their struggle and the myriad injustices suffered by Taiwan’s migrant worker population for various news outlets. The stories came and went, drawing uproar upon publication, then dying a quick death within the regenerating morass of the 24-hour news cycle.

I wanted to do something lasting—more permanent. That’s when the idea struck. I could write a book; a work of fiction based on the brutal reality faced by these people I had come to know and respect.

In the interim, I had visited the Philippines on a pair of occasions. On one trip, I went to report on the drug war in Manila—a war on poverty waged by President Rodrigo Duterte, in which the city’s most disadvantaged regions were stained red with the blood of the innocent and the guilty alike. On the second, I wrote about the city’s cemetery communities, where the poorest of the poor bedded down with the dead in Metro Manila burial grounds.

Again, inspiration struck. I could also draw attention to the conditions faced by those in the cemetery communities; proud people not looking for handouts, but for the simple opportunities granted to those not so poor as they; ways to better themselves through education and employment.

The question remained, however. Should I do this at all? I had not grown up poor. I was not a member of either of these groups of the oppressed.

Finding the answer meant confronting my privilege, and how best to use it to level the playing field. I would write the book, Migrante, a fictional tale of a Filipino fisherman who comes to Taiwan from the Navotas City Cemetery in Metro Manila and experiences the same dangers and indignities suffered upon many of those whom I interviewed in my journalistic endeavors.

I would write it for the fact that it seemed unlikely that anyone within the community itself would have the time to do it themselves—at least not in the immediate future. I would do it because the time was right, and the message was needed. But I would not take their voice—the voice of the exploited—for personal profit. Rather, I would donate the proceeds to groups fighting for migrant worker rights—the Serve the People Association and the Yilan Migrant Fishermen Union. They in turn can use those modest proceeds to continue their fight in courtrooms and education campaigns and in any other form they see fit.

I should use my privilege—as should we all—to help those who have been cast to the bottom rungs of society by the powers that be to climb up, so that we might all enjoy the same level of opportunity.

This is how we, the multiethnic whole that comprise the people of Taiwan, come to achieve true equality in this country, one that has won its status as a global leader in transitional justice and egalitarian values. It may seem overly idealistic, perhaps a touch naïve, but I believe in it just the same as I believe in the nation of Taiwan itself—a country that has earned its independence and freedom with blood and sacrifice.

The days of bloodshed and pain, I hope, are long gone. But the days of learning from past mistakes, and correcting them, should never be over. The ill-treatment, the economic and physical exploitation of blue-collar workers from Southeast Asia who come to Taiwan hoping to better the lives of themselves and their families, is a mistake still waiting to be corrected. They build this nation, just the same as any native Taiwanese, aboriginal, or person from abroad who comes, falls in love with this place, and stays.

Photo provided by Lennon Wong, Chairman of the SPA

But we are not yet equal in Taiwan. Far from it. We live in a system that deliberately divides us, where some are protected under the Labor Standards Act, and some are left vulnerable and without recourse under the law should they be taken advantage of. We live in a place where those from Southeast Asia are often beholden to a corrupt and exploitative brokerage system that leaves many no better off than indentured servants, or at worst, virtual slaves.

In writing Migrante, my message is clear: we must wait no longer to right this damnable wrong. We must act now.

About the author:

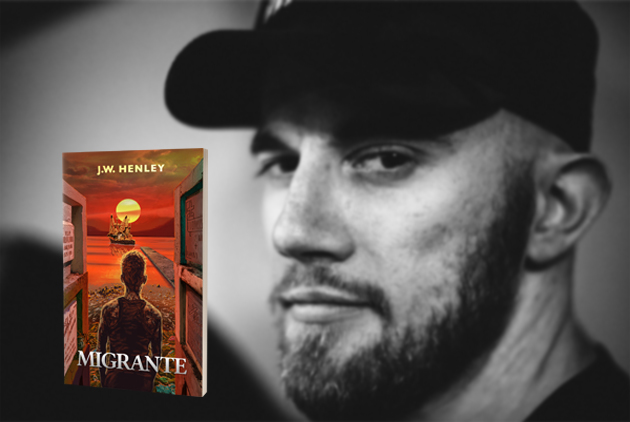

Photo provided by Joe Henley

Joe Henley, otherwise known as J.W. Henley, freelance writer and author. He is originally from Canada, but has called Taipei home for the past 15 years. During that time, he has built up a career writing for print and online media, as well as for television and film. In his spare time, he performs in punk and metal bands as a vocalist, and as such have toured to ten countries around the world thus far. His third novel, Migrante, is a portrayal of the often tragic experiences of Southeast Asian migrant workers in Taiwan.

Excerpt of Migrante:

Rizal looked in all directions: there was only water, the boat, and themselves, no other vessels to be seen on the undulating sea that breathed like a living thing, seething in the encroaching darkness. Li reduced speed to a trawl and emerged scowling, turning on a light above the wheelhouse to illuminate the deck as night descended quickly around them.

Then he showed the men the ways of his primitive setup. A wheel mounted at the stern, strung with a long spool of line, whirred to life, letting out the main line at a slow, steady pace into the sea. Next to the wheel were racks hung with branch lines, hooks, floats, and neon glow sticks. Below the racks were buckets of bait fish, Li removing the lids to let loose a fetid stink that enveloped the deck like a thick cloud of flies. Quickly and without patience Li showed the men how to affix bait to hook, float and glow stick to branch, and then the branch itself to the main line while it flowed steadily past into the water. With speed he affixed several branches to the main and set them loose into the black water below. Then he motioned for the men to do the same, two men working on either side of the spinning wheel. The men worked slowly at first, reticently handling the sharp hooks, struggling to remember the myriad steps Li had taken to do something that to him was second nature, to them as new and bewildering as were the many forces that brought them to this moment ... Read More

- Buy Migrante on store:http://www.jwhenley.com/books/migrante

Have you read?

♦Excerpt of Migrante

♦ Migrant Workers Struggle to Secure Masks in Taiwan amid COVID-19 Fear

♦ The Mother I Never Got to Say Goodbye to

Uploaded by Penny Chiang