When the One in the Dark Speaks, Will You Listen?

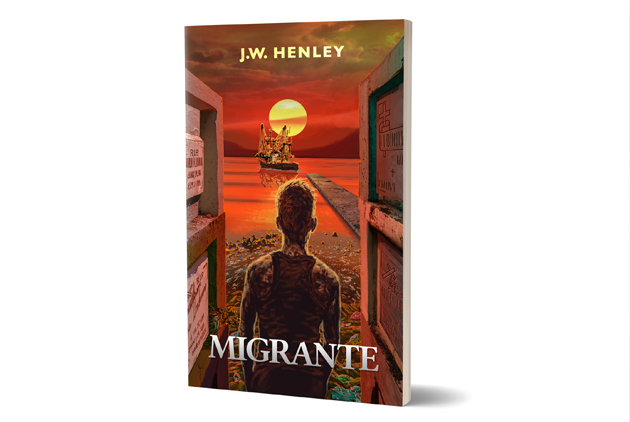

Excerpt of Migrante

Source:Joe Henley

About Author:Joe Henley, otherwise known as J.W. Henley, freelance writer and author. He is originally from Canada, but has called Taipei home for the past 15 years. During that time, he has built up a career writing for print and online media, as well as for television and film. In his spare time, he performs in punk and metal bands as a vocalist, and as such have toured to ten countries around the world thus far. His third novel, Migrante, is a portrayal of the often tragic experiences of Southeast Asian migrant workers in Taiwan.

Views

Excerpt of Migrante

By Joe Henleyweb only

Rizal looked in all directions: there was only water, the boat, and themselves, no other vessels to be seen on the undulating sea that breathed like a living thing, seething in the encroaching darkness. Li reduced speed to a trawl and emerged scowling, turning on a light above the wheelhouse to illuminate the deck as night descended quickly around them.

Then he showed the men the ways of his primitive setup. A wheel mounted at the stern, strung with a long spool of line, whirred to life, letting out the main line at a slow, steady pace into the sea. Next to the wheel were racks hung with branch lines, hooks, floats, and neon glow sticks. Below the racks were buckets of bait fish, Li removing the lids to let loose a fetid stink that enveloped the deck like a thick cloud of flies. Quickly and without patience Li showed the men how to affix bait to hook, float and glow stick to branch, and then the branch itself to the main line while it flowed steadily past into the water. With speed he affixed several branches to the main and set them loose into the black water below. Then he motioned for the men to do the same, two men working on either side of the spinning wheel. The men worked slowly at first, reticently handling the sharp hooks, struggling to remember the myriad steps Li had taken to do something that to him was second nature, to them as new and bewildering as were the many forces that brought them to this moment.

“Gan ni niang, kuai yi dian! Kuai yi dian!” Li shouted, commanding them to speed up. Nervously Rizal reached for a branch and in his haste felt the barb of the hook pierce a finger. With a hiss he dropped the line to the deck and tried to shake away the pain, holding up his injured hand to watch a trickle of blood flow from the wound. He held it up for the captain to see. “Chuanzhang,” he said, pleased with himself that he remembered the word. Li put down his line. He waddled over to Rizal. Rizal looked and saw the captain eyeing his hand.

“Oh,” said Li, feigning sympathy, “hao kelian.” He raised a hand and slapped Rizal across the cheek, causing the others to halt their work and look at Li and Rizal before a glare from the captain sent their eyes elsewhere. “Gan ni niang kuai yi dian! Kuai yi dian!” Li screamed louder than before, again cuffing Rizal upside the head. He pointed to the branch lines. Rizal looked down and took a line. He fumbled with it, hands shaking. With difficulty he managed to affix bait to hook, trying to steady his lip from quivering. He kept his eyes on the main line streaming by and watched the others to see if he was indeed doing as the captain commanded, fearing anything that might again draw the man’s ire. The fear bled into his work but pushed him on, turning the boy’s fright into the man’s will to do what needed to be done.

From time to time Rizal stifled a retch, Li shaking his head and muttering under his breath. For every hook set by the crewmen Li set five or more. In the span of a few hours the oath of gan ni niang became a familiar refrain to the crewmen. Fear of the hand that had already crossed Rizal’s cheek drove them on through their exhaustion. They finished with aching hands, pressing their thumbs into cramping palms to push out the stiffness. The main line at its end, a radio beacon was attached last by Li and he returned to the wheelhouse to push the engine to a brisker pace than the slow trawl he had kept it at while the men worked. Then he came back to the stern, pulling a small flashlight from his pocket to shine down into the water. He pointed at the small fish that flocked around the stern where bits of baitfish and blood had drawn them to their rich scent.

“No,” he said, pointing at the many small fish gathered around. “No good,” he spoke in English. “Weiyu,” he pushed his mottled hands out to the sides, indicating the size of catch they were after. “Tuna.”

Beer Belly knew the word and translated it for the rest of the crew. “Tulingan,” he said. Rizal nodded enthusiastically, hoping to catch Li’s eye. The old man only muttered and pointed to another line, pulling out more hooks to be set. The other two men, standing across the cramped deck from Rizal and Beer Belly, passed a look between them. One elbowed the other lightly and he spoke up.

“Boss,” he said, forgetting the way in which they were instructed to address the captain. “Eat?” the man asked, shoveling phantom food from a phantom bowl into his mouth. He punctuated the request with a smile and a rub of his flat stomach. For the first time since getting in the van with the two men other than Beer Belly, Rizal studied them closely. They were of nearly identical build, skinny with long, narrow faces. He wondered if they might be relatives. Cousins, if not brothers. One was slightly taller than the other, hair a little thinner. Both wore their hair in the same style, parted neatly to the side, though now it was mussed and frayed, slicked with sweat and the blood of the bait fish. The captain turned away from the wheelhouse and stared at the pair of them. He kicked aside an empty chum bucket and moved across the deck toward the man who had dared to ask the question, tilting an ear toward him.

“Ni shuo shenme?” No one aboard the boat understood the words but all knew a question had been asked, one to which there was no right answer but silence. “Zai yi zi,” the captain implored. “Again,” Li said in English. “Say again.”

“Eat?” the man asked again. No sooner was the word out of his mouth than the captain’s quick hand found his cheek just as it had Rizal’s. He caught him full and flush, the sick sound of flesh on flesh cracking through the still night air, sucking all sounds of the boat and the sea into a silent void. The eyes of the others found the deck. Li stood and stared at the man. He raised a hand as if to strike again, reared it back then held it there. The man flinched and the hand fell back to the captain’s side.

“Now, working,” Li said, raising the hand once again to point at the cowering man who stood a full foot taller than him. “Later, eating.”

Buy Migrante on store:http://www.jwhenley.com/books/