Why Taiwan remains an integral part of the EU-US cooperation on China

Source:Shutterstock

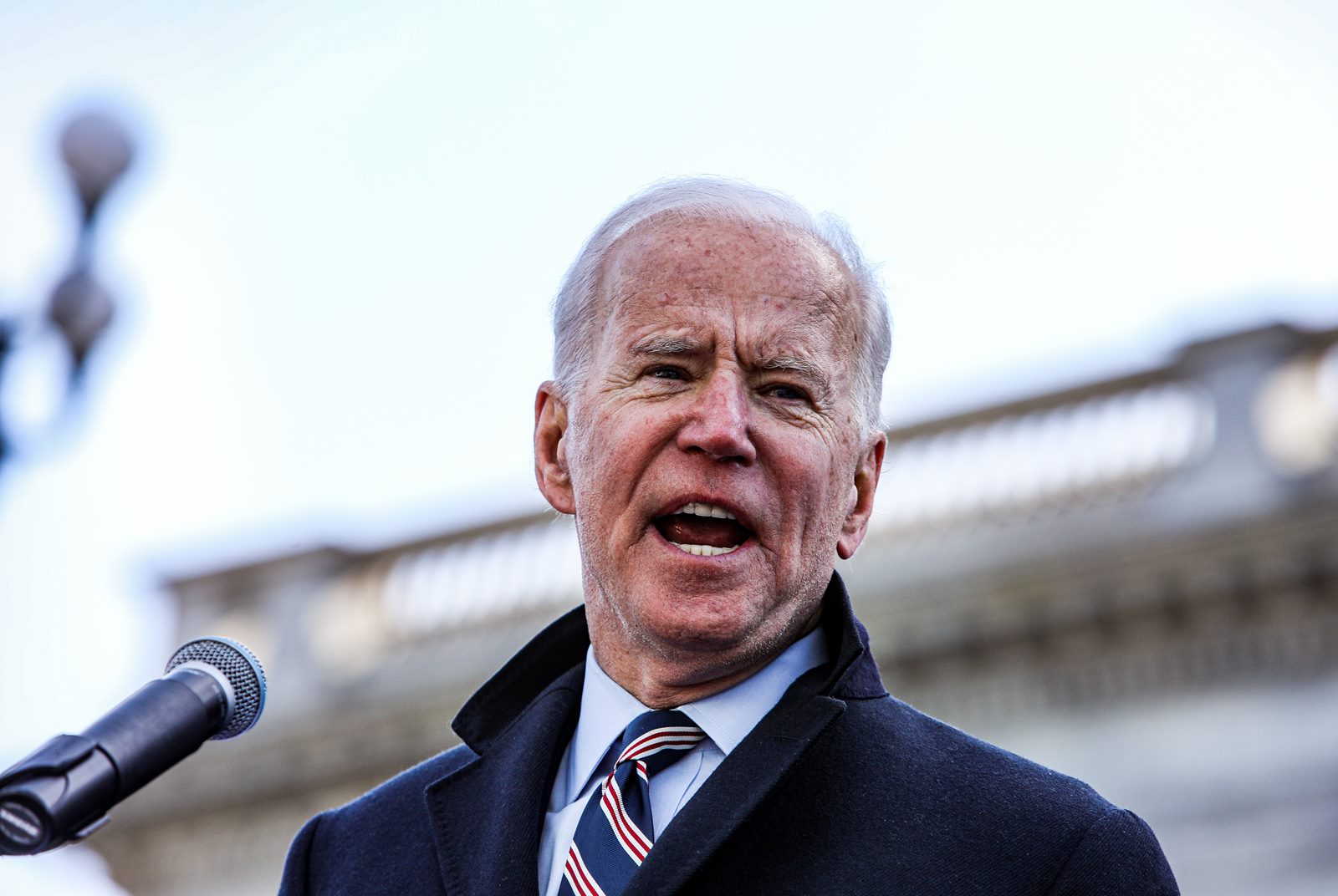

On 15 June, European Commission and Council presidents Ursula von der Leyen and Charles Michel will host US President Joe Biden in Brussels on his first visit to Europe since taking office. There are increasing calls for Europe to upgrade its policy on Taiwan as it rethinks its China strategy, what are the implications for transatlantic relations?

Views

Why Taiwan remains an integral part of the EU-US cooperation on China

By Zsuzsa Anna Ferenczyweb only

On 15 June, European Commission and Council presidents Ursula von der Leyen and Charles Michel will host US President Joe Biden in Brussels on his first visit to Europe since taking office. Both sides expect the meeting to reinvigorate transatlantic relations.

With Covid-19 intensifying the US-China geopolitical rivalry, the European Union has declared that it does not want to be a playground. It wants to be a true geostrategic actor, relying on a solid transatlantic relationship and pursuing an assertive China policy.

Brussels, in fact, wants its own China policy, not one dictated from the outside. But can Brussels ensure such a strategic balance and have its own policy on China?

The message, when first articulated by EU High Representative Josep Borrell in December 2019, seemed clear. Yet, putting it into practice in the context of the EU’s ambitions for ‘strategic autonomy’ and a higher degree of ‘European sovereignty’ has been less clear. Reassurance from Washington that it would not force its allies into an ‘us-or-them’ choice with China still needs time to sink in.

At present, a ‘geopolitical EU’ with a greater potential for independence, self-reliance and resilience in defence and trade, in industrial, digital and health policy is a goal Brussels has yet to achieve. It remains work in progress, as is the case with its Common and Foreign Security Policy (CFSP); noble and global aspirations captured in an ambitious discourse, but undermined by narrow and competing priorities, diverging into twenty-seven directions. The good news is that Brussels is waking up to a new reality, one which is shaped by China’s increasing authoritarian influence in the world.

Within a hostile global context, where democratic governance faces an existential threat, a ‘muddling through’ approach to China that Brussels has maintained is no longer sustainable. More clarity – and credibility – can be secured only if member states back their ambitions with political will to act. For now, the EU’s Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific, published in April this year, is an encouraging step forward that can facilitate maintaining an assertive China policy and strengthen transatlantic relations.

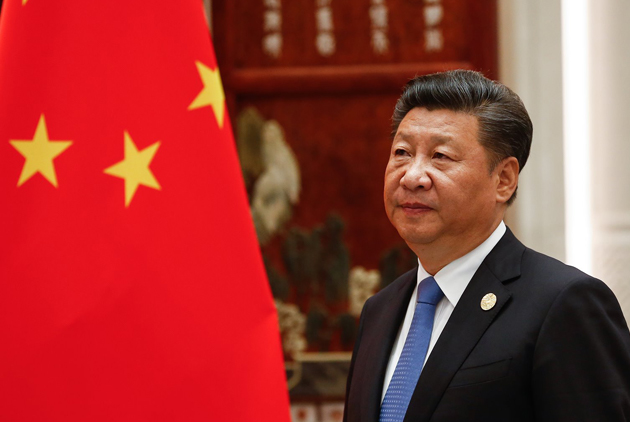

(Source:Xinhua News)

(Source:Xinhua News)

Growing consensus on the ‘China threat’

While appetite for action in Brussels has recently grown, two years down the road following Borrell’s message the EU’s position on China has become even more convoluted, seeking balance between assertiveness and restraint, engagement and criticism. Given the relevance of both the China factor and of transatlantic ties to the future of a ‘geopolitical’ Europe, understanding where these relations are heading is timely.

China’s assertive push to enhance its diplomatic and economic clout, and its military ties with partners such as Russia and Iran, has pushed the US administration to pursue a China policy that is “competitive when it should be, collaborative when it can be, and adversarial when it must be”. At present, no other issue in American politics enjoys as solid a bipartisan backing as the China threat does.

In Europe, awareness of the China threat is equally on the rise. Brussels has revealed its own four labels of China; a cooperation partner, a negotiating partner, an economic competitor and a systemic rival. At the same time, in particular since the pandemic, both Brussels and Washington have started paying more attention to Taiwan and its critical role in new technologies as well as in securing a stable and peaceful Indo-Pacific as an advanced economy and robust democracy.

In April 2020, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen thanked Taiwan for its donation of 5.6 million masks to help fight the coronavirus, in an unprecedented move. There are increasing calls for Europe to upgrade its policy on Taiwan as it rethinks its China policy, if it wants to play a bigger geopolitical role in the world.

Unsurprisingly, Beijing is pleased with neither policy approaches, nor by the fact that in May, in the framework of bilateral consultations, the EU and the US agreed that their individual relations with China are “multifaceted and comprise elements of cooperation, competition, and systemic rivalry”.

This convergence is encouraging in transatlantic relations, and should help revitalize the mutual trust broken under the previous US administration. Signs of convergence are all the more significant ahead of President Biden’s visit to Brussels. The rising acrimony over Beijing’s handling of the pandemic has further catalyzed Washington’s determination to contain China. It has also pushed Brussels to name China, along with Russia, as the biggest source of disinformation concerning the pandemic.

Both sides understand the urgency to show unity and indicate to Beijing that they would be harder to divide. But the reality is that while Washington welcomes a more hawkish EU on China, the two partners have different economic and strategic interests concerning China. Can they coalesce and act together?

(Source: Shutterstock)

(Source: Shutterstock)

China’s push for technology

In 2017, the Trump administration found China’s state-funded policy push for technology “unreasonable, discriminatory and a burden on US commerce”. In 2021, the Biden administration announced it would make critical technology the core of US-China policy, in response to Beijing’s grand ambitions.

Washington also stressed that semiconductors, artificial intelligence and next-generation networks should lead “techno-democracies” against “techno-autocracies”. The sudden global shortage of microchips has further raised the alarm in Washington, and made Taiwan an immediate strategic priority. President Biden warned China will “eat our lunch” if America doesn’t “step up” its infrastructure spending.

When it comes to the EU, speaking with one voice and acting united on China has never been as straightforward, especially when compared to the bipartisan agreement currently reigning in Washington. For the future, the EU and the US working together on sensitive technologies will be key to an effective response to the ‘China threat’.

Thus far, the EU has maintained that dialogue with Beijing must remain, no matter the depth of tension in bilateral ties. Yet, consensus is growing on the need to develop protective tools against Chinese influence. EU institutions have stepped up criticism that President Xi’s ambition to make China a major industrial competitor in high tech is violating WTO terms by leveraging state resources and extending the state’s reach into the economy.

Brussels also introduced several robust measures against perceived overseas threats, including an investment screening mechanism, and more recently legislation it tabled to crack down on state-owned enterprises from outside the EU. It also agreed on a revised export control regime on cyber-surveillance and facial recognition software that can be used in human rights violations, and issued a toolbox 5G security and an action plan on disinformation.

Among the most prominent measures, these reveal that with political will and greater coordination, there is a lot that Brussels can do to address the China threat. But there is more it must do now.

Stepping up support for Taiwan’s participation in international organizations, as well as launching an impact assessment, public consultation and scoping exercise on a Bilateral Investment Agreement with Taiwan before the end of 2021 must be part of these efforts.

More for more

For the assertive shift in Brussels to be sustainable, member states must use the momentum their effective coordination has brought. Judging by the measures taken, the Commission understands that whoever sets technology standards will shape the future. Jointly responding to China’s push for tech leadership within the transatlantic alliance is therefore the right path to follow.

In December 2020, before US President Biden took office, the Commission proposed establishing a new EU-US Trade and Technology Council, to strengthen joint technological leadership and develop compatible standards, a call it renewed in March this year.

Yet, EU High Representative Borrell also said at the time that for Brussels, the Commission’s proposal was not about siding with the US to outflank China and prevent it from dominating important economic and technological sectors. “That would be a crazy objective. We need China”, he stated, despite already having acknowledged that China was prepared “to use its technological and military advantage to enhance its political influence”.

In this light, when in December 2020 the European Commission decided to conclude a Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with China (CAI), Washington was not pleased Brussels ignored its calls for earlier consultations. There remain important obstacles in EU-US relations in technology, namely over data protection, privacy and data transfer, over surveillance and big data content. In order to cooperate on the China threat, it is vital they adequately address these differences.

(Source: Shutterstock)

(Source: Shutterstock)

MEPs showing the way forward

The months following the agreement in principle on CAI have impacted EU-China relations even deeper. In March, for the first time in three decades, in coordination with Western allies, the EU imposed sanctions against four Chinese officials over human rights violations of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. In retaliation, Beijing imposed its own sanctions on diplomats, on national and European parliamentarians, the Human Rights Committee (DROI) of the European Parliament (EP) and the EP’s Political and Security Committee (PSC), as well as several European think tanks.

For now, in Brussels it is the EP that has spoken in the clearest and strongest terms on China, as well as in support of Taiwan. MEPs have used their power – albeit non-legislative in CFSP – to speak their truth and refuse to ratify the CAI. After the sanctions China imposed on five MEPs, the House made clear they would never ratify the deal. Europe is no “punching bag”, EP President David Sassoli said to China.

And they lived up to their commitment; in May MEPs overwhelmingly voted to freeze the ratification of the investment deal. MEPs condemned the sanctions, calling it “an attack against the European Union and its Parliament as a whole, the heart of European democracy and values, as well as an attack against freedom of research”. Through the resolution, MEPs committed to not open the debate on the deal as long as sanctions remain in place.

In fact, what the sanctions seemed to have achieved is to strengthen willingness in the EU to engage Taiwan, and serve as inspiration to further warm ties.

MEPs are at present working on their first stand-alone report on EU-Taiwan relations, indicative of a tangible interest in the EP is seeing Taiwan on its own merit, not only through the lens of EU-China relations.

Looking forward

The extent to which Brussels maintains its tougher stance on China will shape the depth of transatlantic cooperation on China. Washington’s approach to Brussels, in light of President Biden’s visit to Europe, will be just as important for the resilience of transatlantic relations. But ultimately, it is the degree to which Beijing will honor its international commitments and respect the rules-based international order that will be decisive to how the EU and the US approach China.

Washington’s foreign policy is driven by the ‘China threat’ embedded in its Indo-Pacific Strategy. The geopolitical rivalry with China, driven by the race for tech supremacy has overwhelmed every other issue on Washington’s agenda, including transatlantic relations, as well as Russia. Ignoring the latter carries significant risks not only for Europe’s security, but also that of America, as it might embolden the Kremlin to be more repressive at home and aggressive abroad.

Washington needs allies to effectively address the China threat.

Brussels knows it needs to work with Washington on a common approach to critical technologies, one that is rooted in transparency, reconciles their differences when it comes to data and privacy, and enables the two sides to cooperate and include Taiwan in these efforts.

But a strong alliance will only work if Washington considers Europe’s complexities on China as they play out in Europe on multiple levels, and the weaknesses and strengths they entail.

Brussels and Washington must accommodate the priorities they each have on China, but also on data, trade and defence. To be a ‘geopolitical’ actor in the Indo-Pacific, Europe must share responsibilities with the US in shaping the emerging new reality.

The way forward is to identify connections between their Indo-Pacific strategies, namely in connectivity and infrastructure where interests converge, and seek a viable alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

The Biden administration seems determined to prioritize infrastructure investment following the launch of a multi-trillion infrastructure and jobs package in March, promising increasing financing in new technologies. Brussels also identified fibre optic and 5G infrastructure as a key area of investment for the Recovery and Resilience Facility to support its digital and green recovery.

Brussels and Washington should stop asking ‘whose China policy’ is more effective, and instead recognize that a ‘common’ approach can be pursued based on their common values and the convergence in their priorities in the Indo-Pacific. They equally have a common interest in developing closer relations with Taiwan as a like-minded partner on human rights, democracy and rule of law.

“Can democracies come together to deliver real results for our people in a rapidly changing world?”, President Biden asked before his Brussels visit. The answer lies in a strong transatlantic alliance, one that includes Taiwan.

Should you be interested in submitting op-eds, please email to [email protected]

About the author:

Zsuzsa Anna Ferenczy is a Ph.D. research fellow at the European Union Centre in Taiwan at National Taiwan University, Taipei; affiliated scholar at the Political Science Department at Vrije Universiteit Brussel; head of associate network at 9dashline; and former political advisor in the European Parliament (2008-2020). She tweets @zsuzsettte

Have you read?

♦ Are Chinese and US Maneuvers in the Asia-Pacific a Precursor to War?

♦ Taiwan Strait: Time for a ‘Cold Peace’ or a ‘Hot War’?

♦ Is Taiwanese society ready to face a belligerent China?

Uploaded by Kwangyin Liu