Time for migrants in Taiwan to become immigrants?

Source:Pei-Yin Hsieh

Big investment projects and COVID-19 border restrictions have conspired to cook up Taiwan’s biggest labor shortage in 30 years. It is time for Taiwan to bid adieu to its cheap labor mindset and allow migrant workers to become immigrants.

Views

Time for migrants in Taiwan to become immigrants?

By Pei-hua Lu, Linden ChenFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 737 )

Taiwan has opened its doors to foreign workers for more than 30 years, but never has it needed them more than now.

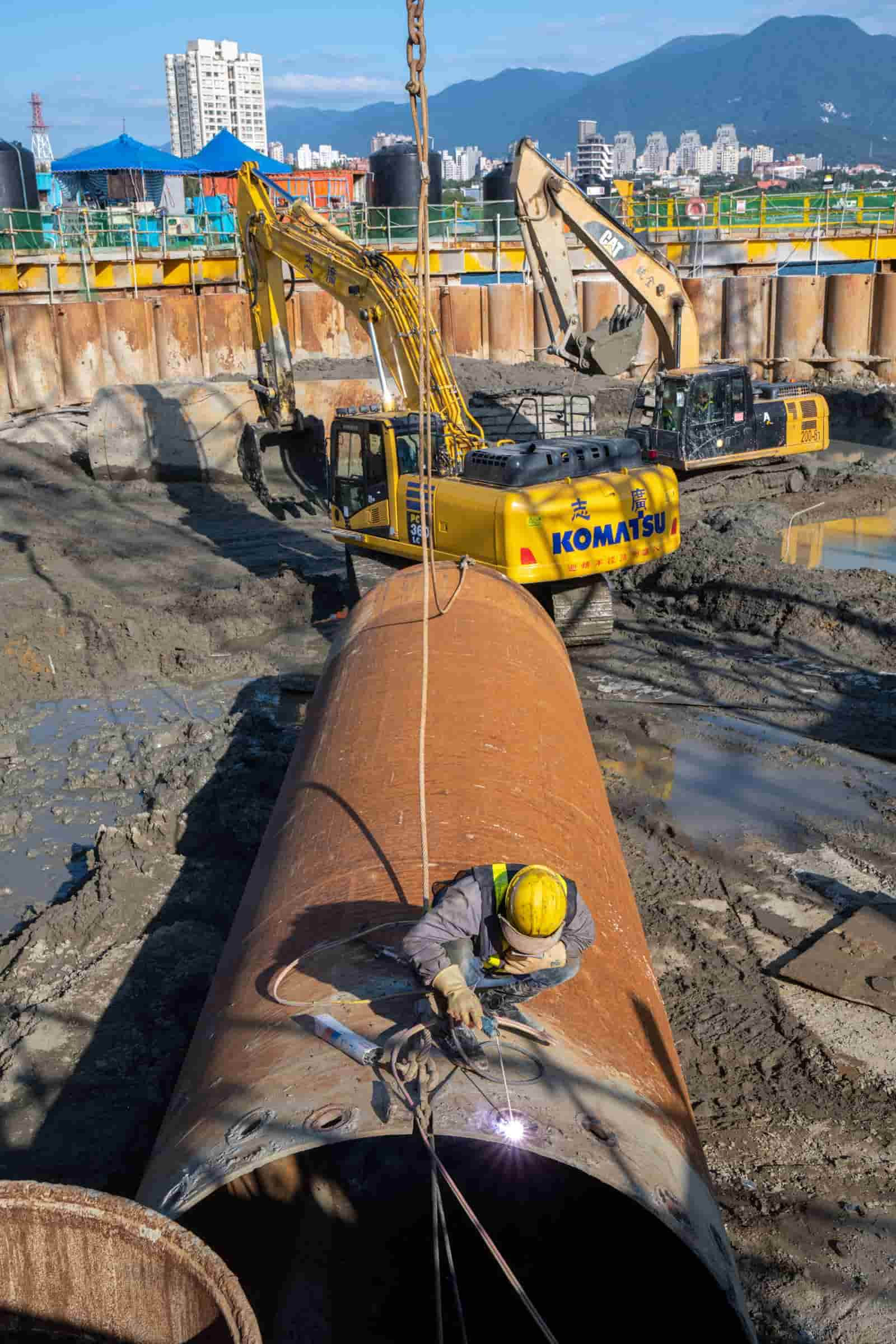

The Danjiang Bridge project in northern Taiwan is a perfect example. Designed by the late Zaha Hadid, it will be the world’s longest single-tower, cable-stayed bridge when completed, but getting there has been a grind because of a severe labor shortage.

“We have a quota for 306 migrant workers, but we’ve only been able to get 109 so far,” said Chiang Chi-ching (江啟靖), the general manager of contractor Kung Sing Engineering Corporation (KSECO).

The government has repeatedly loosened restrictions on bringing in construction workers from abroad to ease the shortage, but the inflow of labor was frozen in May 2021, when a serious COVID-19 outbreak in Taiwan led to strict border controls that have yet to be lifted.

As a result, construction companies face a nightmarish situation: migrant workers in Taiwan are being poached by other companies but new people cannot be brought in from overseas to replace them.

The problem has been exacerbated by two separate phenomena – a massive expansion in capacity around Taiwan by TSMC, the world’s biggest contract chipmaker, and the increase in investment in Taiwan by Taiwanese manufacturers in China to avoid the higher tariffs imposed on Chinese-made goods by the United States starting in 2018.

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

The resulting higher demand for labor has forced companies to bid up wages. “Contractors at construction sites need to offer triple wages to get workers, and they pay them in cash by the day,” said Lee Chao-chin (李超群), CEO of foreign labor broker Kang Lin International Commercial.

Sacrificing the ailing and elderly to high wages

The race to attract workers with higher wages has been fueled by the need to keep construction projects on schedule.

“The human resources cost of a migrant worker, not including overtime, is now over NT$40,000 a month,” Chiang said, well above the current minimum wage of NT$24,000.

The construction sector is simply a microcosm of the problems facing other parts of the economy. Several executives at manpower powers said that for the first time in history employers no longer can choose from a large pool of prospective employees. Instead, the average migrant worker today can pick from over 10 jobs on offer.

Long-term care operators in central and southern Taiwan have seen foreign caregivers bolt to construction sites to get paid by the day, leaving nobody to care for the elderly; families without deep pockets that have elderly care needs are being sacrificed.

In effect, families that want to hire caregivers are at the bottom of the recruiting food chain. Domestic caregivers only make NT$17,000, NT$7,000 less than migrant workers employed by companies. In the first five months of 2021, there were 1,751 caregivers who switched for factory or construction jobs, six times the number seen in all of 2020.

Employer groups complained about the trend earlier this year, and the Ministry of Labor agreed in August to raise the threshold migrant workers have to meet to change jobs. Priority is given to employers in the same field to hire the worker, and only if no other employer makes a hire in 14 days can the worker change industries.

The recent chaotic pursuit of labor around Taiwan has been mainly driven by the investment wave and COVID-19 pandemic, but structural components are also at play. Almost all Taiwanese go to college, reducing the availability of basic manual labor, and industrial employers have had to recruit and rely on overseas laborers to fill the gap.

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

Also, Taiwan’s labor force is shrinking. The Ministry of the Interior estimated that more people will retire from the workforce (329,100) in 2021 than enter the job market (320,800) for the first time.

The wage dilemma: Taiwan not competitive

Without migrant workers to pick up the slack, Taiwanese society is having trouble functioning, but will reopening the country’s doors to overseas workers automatically solve the problem?

Regrettably, the answer is no, largely because the competitive edge Taiwan has had in recruiting migrants is gradually disappearing.

One manpower broker said Taiwan had an advantage early on because migrant workers were protected by the Labor Standards Act. That meant they could make the minimum wage and get a raise when the minimum wage went up, leaving them better paid than if they worked in Singapore or Hong Kong, the broker said.

But other countries have increased wages for migrant workers in recent years, and now Taiwan’s wages for industrial workers are lower than anywhere else in Asia except for Singapore, and even there Taiwan’s edge is narrowing.

The real challenge for Taiwan is coming from Japan and South Korea, which have opened their doors to workers from Southeast Asia.

Cheng An-chun (鄭安君), a lecturer at Sagami Women’s University in Japan, said Japan addressed labor shortages in the past by bringing in Chinese nationals as “technical interns” while South Korea turned to ethnic Koreans in China and Russia.

But as China has prospered, fewer Chinese need to go abroad to find work, forcing Japan and South Korea to shift their focus to migrant workers from Southeast Asia, Cheng said.

The changing focus has dealt a blow to Taiwan, which finds itself increasingly marginalized in the migrant worker labor market because of the relatively high wages paid for industrial work in Japan and South Korea.

In Japan, for example, the Chinese “technical interns” that once made up more than 70 percent of its overseas workers now account for less than 20 percent. Japan began allowing in people with specified skill visas in 2019, leading to the recruitment of foreign caregivers. Its top three targets have been Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines, the same countries where Taiwan finds most of its overseas caregivers.

“It used to be that when you went to Vietnam to find workers, if you needed 100, 400 candidates would show up. Now, only 90 show up because they would rather go to Japan and South Korea,” said Lee, the manpower agency CEO.

The other problem for Taiwan is that fewer Southeast Asian countries are exporting labor as they grow stronger.

Thailand is a clear example of that. It is now supporting the development of its own industrial sector by providing no-interest loans to workers, but at one point it was the main source of labor for Taiwan’s public infrastructure projects, peaking at 140,000 workers. Today, fewer than 60,000 Thai workers remain.

“If our policies don’t change, Taiwan will not be able to find workers,” Lee said.

Time to recalibrate migrant worker policies

With the global labor market battle underway, the days when Taiwan could bring in large numbers of migrant workers are numbered. At the same time, the emergence of the poaching of workers as the “new normal” indicates that treating migrant workers as cheap labor is no longer viable.

Taiwan is entering the ranks of developed countries, and the answer to its labor bottleneck may be to turn migrant workers into immigrants.

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

The Ministry of Labor (MOL), which is responsible for the country’s labor supply, has come under pressure to address the problem.

“The labor shortage is a reality, and we have to use migrant workers to fill the gap,” said Tsai Meng-liang (蔡孟良), the director-general of the MOL’s Workforce Development Agency.

Attitudes were far more conservative 10 years ago, when concerns existed that overseas workers could take away opportunities from Taiwanese and controls were put in place, Tsai said. But as the country’s labor structure changes, those policies need to be adjusted.

Tsai admitted that beyond continuing to open the labor market to migrant workers, policies designed to keep the best of them in Taiwan will be a new priority that could take shape as early as next year.

If migrant workers can be given immigrant status on a conditional basis, it could motivate them to perform their best on the job, which would benefit both their employers and society. Getting residence status could allow their relatives to live in Taiwan, giving employers a stable source of manpower over the long term.

The German experience

Germany, which relies on large numbers of migrant workers to fill basic level jobs and drive economic activity, has a system that might be worth studying.

Germany imported large numbers of migrant workers from southern Europe and Turkey in the decades following the end of World War II because of ongoing labor shortages. The workers were initially seen as temporary labor, but they have since been more accepted through a succession of legal revisions.

Chang Chih-wei (張志偉), an assistant professor in Ming Chuan University’s Department of Public Affairs who has studied German immigration law, said that after Germany passed its first immigration law in 2005, migrant workers could strengthen their claim to residence status simply by proving they could assimilate into German society.

Such proof could include getting German language certification, completing cultural classes, or having a financial foundation, and would help get migrant workers visa extensions, permanent residence, and even German citizenship.

Having evolved from a guest worker model to an immigration model, the German strategy provides a roadmap for advanced countries for alleviating labor shortages.

Chang said Taiwan’s treatment of domestic caregivers and industrial migrant workers remains stuck in the German guest worker phase of 50 years ago but with even fewer favorable conditions, including different pay for equal work and migrants not allowed to apply have their families or spouses back home live with them in Taiwan.

In fact, Taiwan has a long road ahead if it hopes to emulate the German experience.

At present, Taiwan’s Labor Standards Act only applies to two types of migrant workers: industrial laborers and caregivers in long-term care institutions. More than 200,000 caregivers who work for families make less than the minimum wage.

Lee, the foreign labor broker CEO, believed the era of cheap migrant workers will not return. “In the future, the cost of hiring migrant workers and their salaries will only go up; they will not go down,” he said.

He pointed to the trend of labor exporting countries and supply chains advocating a policy of “zero expenses for migrant workers,” hoping that employers take on the cost of air tickets, physical check-ups, and brokerage fees that the migrants typically shoulder at present. “The international trend is that users [employers] should pay,” he said.

Beyond wages, the protections afforded migrant workers in Taiwan lag behind the market. Caregivers live in the homes of the families that employ them and are virtually on duty 24 hours a day. Yet they receive no overtime pay and are even asked to do household chores, all of which infringe on the workers’ rights.

Improving wages, benefits, and time off

Taiwan International Workers’ Association researcher Wu Jing-ru (吳靜如) said manufacturers in Taiwan enroll their overseas workers in the national labor insurance program, but the coverage for migrants does not include unemployment benefits. So whenever foreign workers complain they have been shortchanged on overtime pay and quit their jobs, they cannot get unemployment benefits and are forced to borrow money to survive.

By contrast, migrant workers employed by long-term care institutions in Japan not only are paid the same wage as their Japanese counterparts for the same work, they also get time off and are eligible for profit-sharing plans.

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

Wu believes that Taiwan should enact a law that safeguards rest periods for foreign caregivers, including at least 11 consecutive hours off per day, and stipulates that employers can apply for home respite services when a caregiver takes leave.

Chang contended that while wages in Taiwan will not catch up with South Korea and Japan in the short term, Taiwan’s democratic environment and human touch remain attractive to migrant workers.

But that may not be enough. Swiss writer Max Frisch once wrote, “We asked for workers; we got people instead,” a reminder that we cannot ignore the dignity of cross-border workers.

Taiwan’s industrial sector and families depend heavily on the 700,000 migrant workers in the country; they have in fact long been indispensable and a backbone of Taiwan’s economic stability. It is now time to afford them a more stable future.

Have you read?

♦ The Rootless: Migrant Labor through the Eyes of the Oppressed

♦ “We’re tired but we’re happy to help”: how Macau migrant workers organized during the pandemic

♦ “I just continued, continued and continued”: the circular migration of an Indonesian domestic worker

Translated by Luke Sabatier

Uploaded by Penny Chiang