The Global Talent Battle

Taiwan under Siege

Source:CW

Taiwan is facing the potential collapse of its talent pool and could face the most serious talent shortage of any country in the world by 2021. What can it do to fend off raids from other countries and get back in the talent game?

Views

Taiwan under Siege

By Sherry LeeFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 550 )

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Asian Career Fair in early March had a distinctly Chinese and Japanese flavor. The Ping An Group and Baidu from China, Toshiba from Japan, and even local-level research agencies like the Wenzhou Institute of Biomaterials and Engineering had representatives there. But among the many multinational enterprises and organizations that had a presence at the fair, not a single one was from Taiwan.

MIT's renowned "Media Lab," home of the innovation that spurred Google Glass, often brings change to the world through the most cutting-edge research and applications. It attracts about NT$1.3 billion in research funds every year from nearly 80 companies.

The list of sponsors includes renowned companies from many different fields, as diverse as Gucci, Bloomberg and Microsoft. More recently, the biggest contributions have come from Asian corporations, such as Chinese electronics vendor TCL Corporation, Japanese consumer electronics brand Panasonic, Singaporean telecom operator Singtel and South Korean electronics giant Samsung.

Electronics stalwarts from China, Japan, South Korea and Singapore all sponsor the Media Lab program, but, again, Taiwanese companies are nowhere to be seen, an illustration of how Taiwan has fallen behind in the fierce fight for the world's top young minds.

The Media Lab offers a special perk to big donors – they are allowed to send one scientist to work at the lab, and Samsung takes advantage of the opportunity more aggressively than anybody else.

Taiwanese native Wu-hsi Li, who earned a doctorate from the Media Lab, says Samsung scientists do whatever they can to make friends with everybody, taking people out for meals, chatting with them, and living alongside students and teachers to get the inside scoop.

"Even before everybody's projects have been presented, they already know what's in them," Li says.

With its people keeping a close eye on future trends 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, Samsung has bought a front seat to the future, and also pocketed a VIP pass to the hunt for elite talent.

Country and Company, Hunting for Talent Abroad

Nan-wei Gong, who has a materials science degree from National Tsing Hua University and graduated with a Ph.D. from MIT last year, was part of the winning team of the prestigious MIT $100K Entrepreneurship Competition in May 2013. Backed by its powerful intelligence network, Samsung identified Gong as a budding talent and invited her to an interview on the West Coast eight months before she graduated. When Samsung offered her about 50 percent more than she expected, she exclaimed: "I wanted 50 cents and they offered me a dollar."

Gong was just one of many MIT phenoms that Samsung approached. Pointing to the Media Lab area, she says with emotion, "There are two labs in this area with about 30 to 40 graduate students. Samsung hired five of them. It essentially moved out all of my close friends."

In the end, however, Gong passed on Samsung's offer, deciding instead to start her own business.

Samsung has leveraged high pay and its huge platform to grab the best minds from around the world. Almost all of the MIT students that CommonWealth Magazine talked to predicted that Samsung's aggressive hunt for talent would make it the industry leader in wearable devices and other technological applications in the near future.

This unprecedented movement and mixing of talent has spawned fierce competition for elite minds across oceans and continents, and companies and even countries are penetrating foreign camps, "using other countries' soldiers to fight their battles."

Taiwan's Dire Talent Deficit

For Taiwan, however, the trend is moving in the opposite direction. A report titled "Global Talent 2021" published by global forecasting firm Oxford Economics in 2012 estimated that by 2021, Taiwan will face the greatest mismatch between supply and demand for talent of any major economy around the world. Its talent deficit will be even more dire than in Japan, which already is grappling with a serious aging population problem.

The report calculated the talent gap in 46 countries by taking the rate of growth in the supply of talent in each country and subtracting from it the rate of growth of demand for talent dictated by economic development. A positive result indicated a talent surplus, a negative result a talent shortage, and these results formed the basis of the talent gap rankings. The "talent" described in the study referred to skilled workers – the executives, professionals and technicians essential to a country's development.

Taiwan emerged as the country with the largest talent deficit among the nations studied mainly because of the forecasting firm's positive perception of Taiwan's economic future.

Philip Thomas, senior economist at Oxford Economics, said Taiwan did not have "something wrong with the supply side" in the company's forecast. The serious talent deficit, he says, resulted from his company's expectation that Taiwan would continue to sustain strong growth and demand high-end skilled manufacturing and services.

"Demand is very strong, compared to other countries. That's why Taiwan's got quite a large deficit. It's driven by demand," Thomas says, foreseeing that there will be a shift in demand toward more skilled workers as the industrial structure of the economy changes.

The report said Taiwan's most serious shortfalls would be in management and professional talent, the kind of talent that can only be developed through long-term cultivation and supportive government policies. Based on current trends, that spells trouble for the country.

The Decline of Elite International Talent in Taiwan

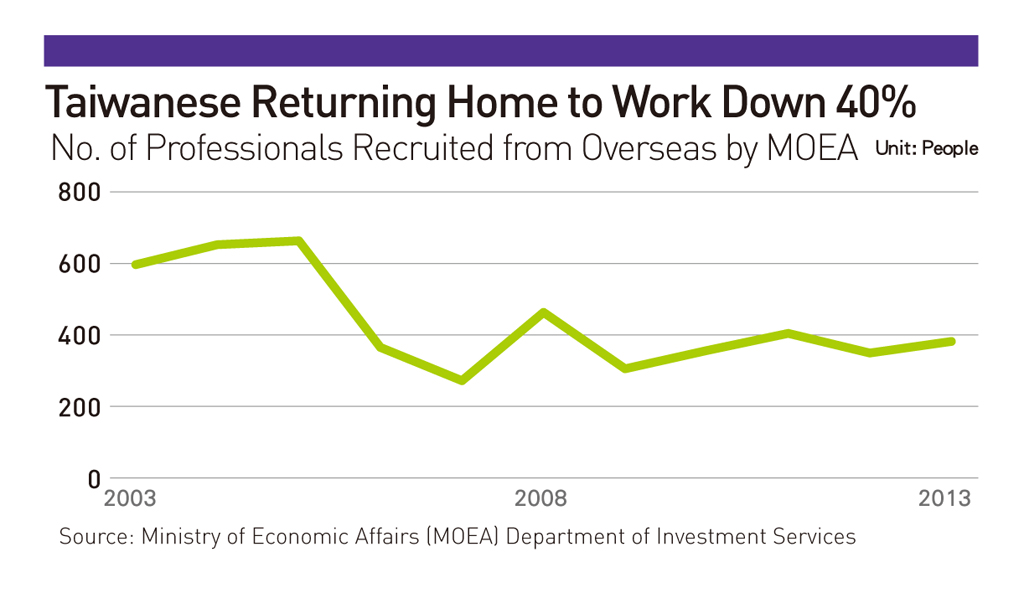

CommonWealth Magazine looked at the Ministry of Economic Affairs' HiRecruit program to see how effectively Taiwan is recruiting international talent. It found that from 2003 to 2012, the number of overseas skilled workers recruited to work in Taiwan (mostly Taiwanese expatriates who have studied or worked in the U.S.) fell by about 40 percent from a high of just over 600 people per year. (Table 1)

As is the case in international trade, potential top-flight academic talent is also on the decline.

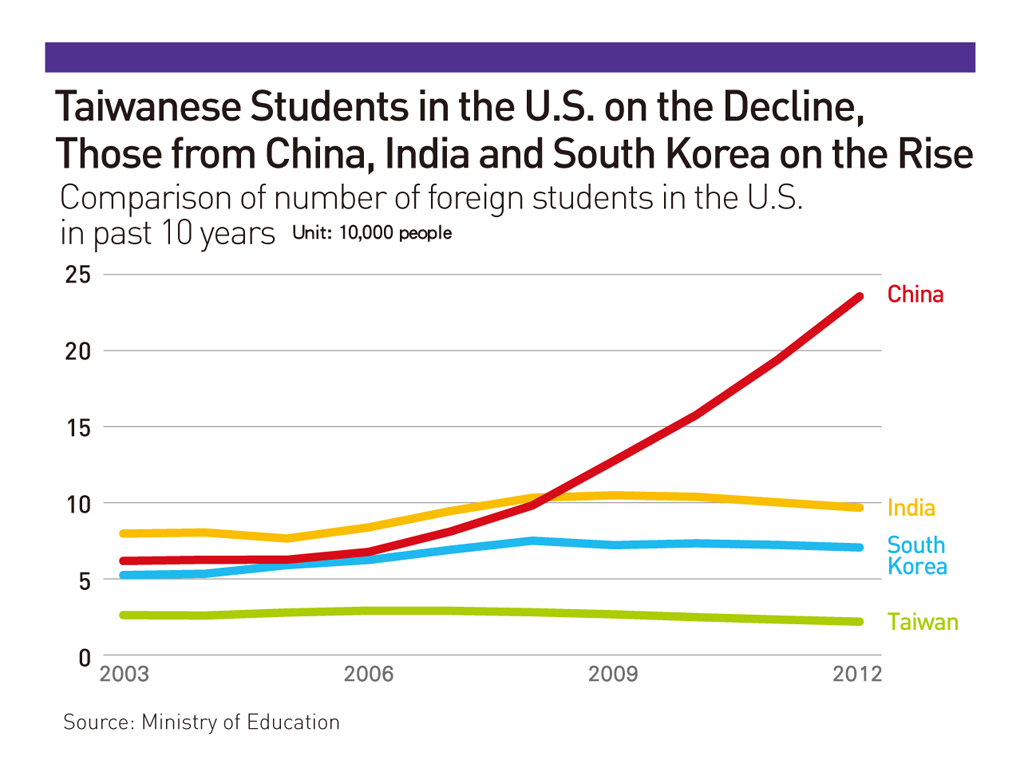

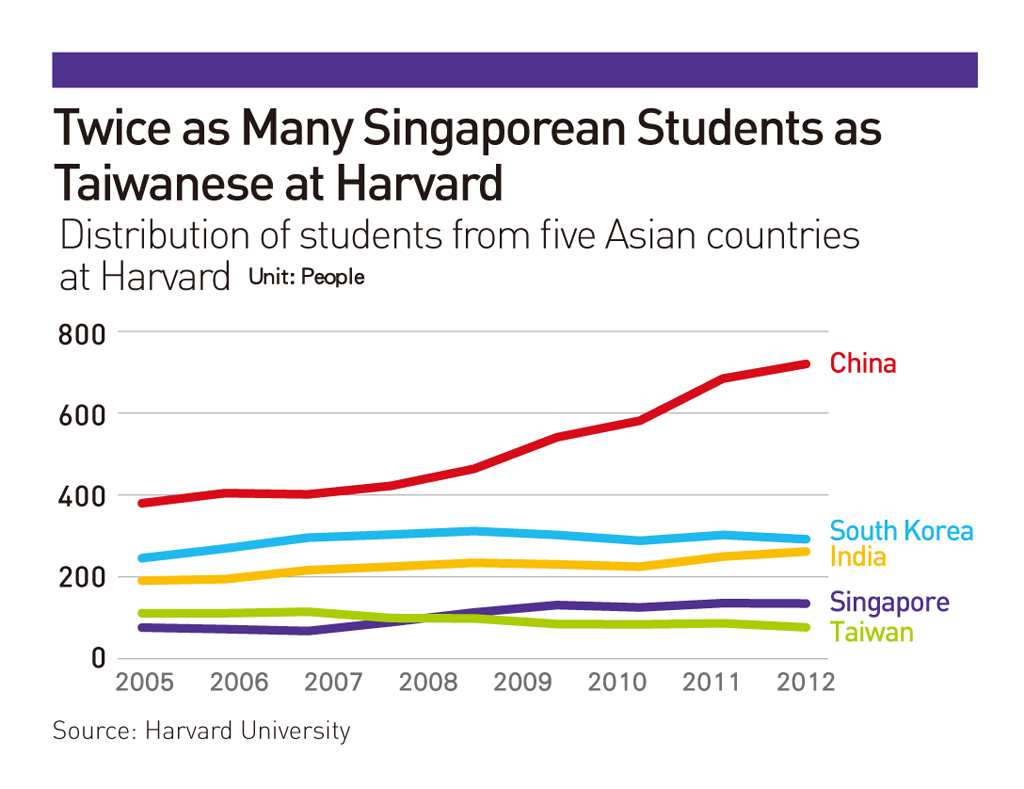

In 2007, there were 29,000 Taiwanese studying at American universities, compared with 22,000 last year, a drop of 24 percent, while the number of Chinese, Korean and Indian students in the U.S. has been growing at a double digit rate over the same period. (Table 2)

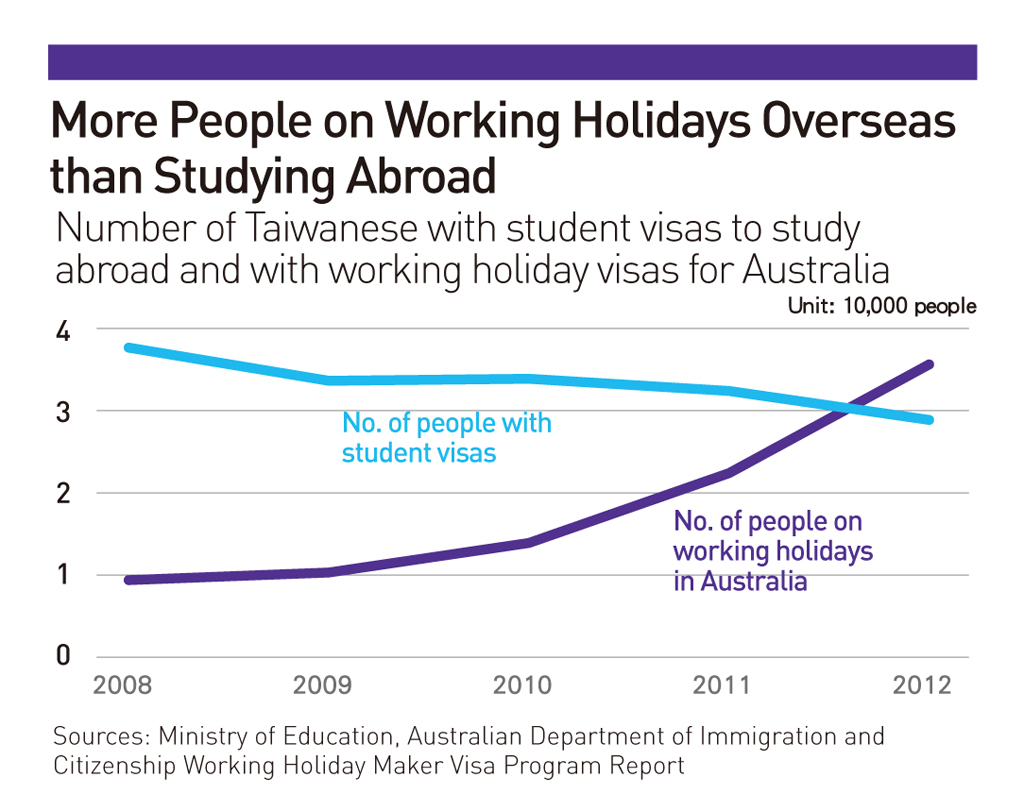

Also, the Taiwanese heading to the United States to study are now outnumbered by those traveling to Australia on working holidays, usually to perform manual labor. (Table 4)

Unlike in Taiwan, many countries have scrambled for solutions and made upgrading talent a national priority in response to the huge changes in demographic trends, talent requirements and the nature of jobs in the 21st century.

National Talent Strategies

Talent strategies often involve increasing a country's population over the long term and cultivating or recruiting world-class talent in the shorter term (five to 10 years).

China has already taken stock of the situation and established a few talent indicators it hopes to hit by 2020, including grooming around 100 strategic entrepreneurs to lead Chinese enterprises into the ranks of the world's top 500 companies and building the workforces of state-run enterprises to include 40,000 international business professionals (at least half of them to be recruited on the open market).

Singapore, which has always followed an open-door policy on foreign talent, intends to be even more open in the future.

More than 1 million foreign nationals work in Singapore, about a quarter of the city-state's total workforce. But Singapore continues to focus on neighboring countries in its hunt for talent, and it rounds them up well in advance. It hopes in 2015, for example, to increase the number of foreign university students in Singapore to 150,000, or about 20 percent of the total.

Singapore has also put a priority on nurturing its own people into world-class professionals.

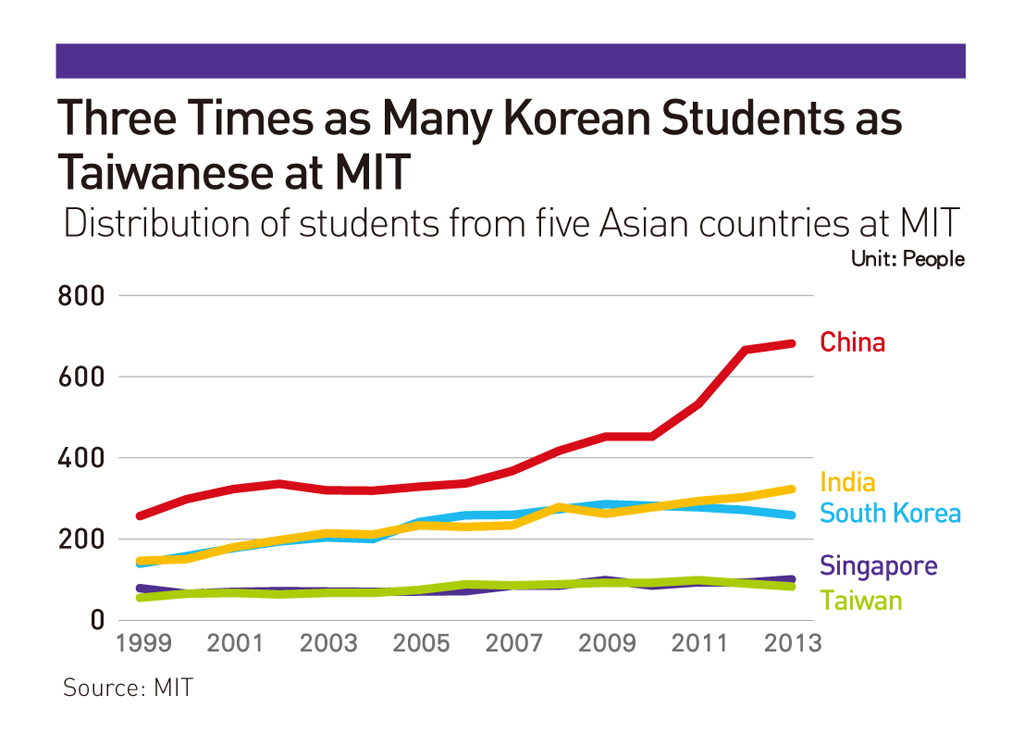

Over the past 10 years, the number of Asian students attending Harvard and MIT has risen dramatically, with Singapore leading the way. It has as many students enrolled in the two prestigious institutions as Taiwan, despite having only a quarter of Taiwan's population. (Table 3-1, Table 3-2)

Maria Brennan, the assistant director of MIT's International Students Office, says the category of student that has grown the fastest are one-year, non-degree exchange students that attend MIT on a J1 visa (for exchange visitors).

That's because Singapore invited MIT to help establish Singapore's fourth university, Singapore University of Technology and Design, leading to the one-year exchange programs. By pushing institutional innovation through international alliances, exchange programs and scholarships, the government wants to foster elite students who have learning experiences in the United States, China or Japan.

Why are so few Taiwanese students taking advantage of MIT's one-year exchange program?

"It may be simply that Taiwan and Taiwanese universities are not aware of it," says Brennan. "It is a non-degree program, but certainly they come here and get new ideas. It is a transforming factor for them."

Even South Korea, which has traditionally been preoccupied with the origin of its talent (at the expense of foreign nationals), has begun to abandon its old mindset and shown a willingness to go beyond its borders and recruit whatever professionals it needs. It has recently begun, for example, to issue work visas to software specialists and doctors and nurses from India.

In their hunt for talent, the Koreans have also demonstrated psychological savvy, deciding to set up innovation bases overseas where talent is clustered because they know full well that many international professionals are unwilling to live in Korea.

Samsung quietly built a "Samsung Strategy and Innovation Center" in Silicon Valley that opened last year, and it later surprised the industry by hiring Indian-born whiz kid Pranav Mistry, recognized as one of the top inventors in the world, and Henry Holtzman, who was the MIT Media Lab's chief knowledge officer.

Beyond South Korea and Singapore, many other countries see the government's role as searching for and recruiting elite talent that can catalyze industrial upgrading in key sectors.

International Minds, Thinking Hands

In the worldwide pursuit of talent, two types of people are at the top of the list: "international minds" and "thinking hands."

And the demand for workers with global operating skills and thinkers with application skills is only bound to grow.

One such talent is 33-year-old Rock Ma, the founder of consulting firm PARC and an expert on the sheet metal used in car bodies, who was holding a class at an Audi-authorized auto body repair shop in Beijing when CommonWealth caught up with him. His fee for the day was NT$33,000.

Ma, a native of Miaoli County, represented Taiwan in winning a gold medal in auto body repair at the World Skills Competition in 2001, but Taiwan was unable to retain his talents.

Compared with the benefits Japan and South Korea give their champions, such as life-long employment at a company, a house and an international stage, Taiwan does not seem to value vocational skills, leaving Ma feeling that "in Taiwan, a gold medal is not real gold."

Two years ago, Ma's technical skills won the regard of several high-end German automakers with factories in China. Invited to China to work, he now trains auto body technicians for Jaguar, Porsche, Audi and others.

In addition, 20 to 30 vocational schools along China's coast have hired him to teach classes. Through his experience, Ma has gained a real appreciation of how strongly China's government and private sector support vocational education.

"The private and public sector and academia are bound together. Talented people pass on their technical skills to the students. Their goal is clearly to develop world-class auto body repair champions and enhance the car industry's repair skills," he says.

Taiwan, on the other hand, has moved in a different direction. Taiwanese society has turned inward and even tried to seal itself off from the outside world in recent years. Its small and medium-sized enterprises have treated relocating factories to China as a substitute for globalization, creating major imbalances. Because of the success of the Hsinchu Science Park and Taiwanese electronics contractors, Taiwan has also concentrated excessively on the high-tech sector and improved yield rates at the expense of innovation and risk-taking.

Compounding the problem is that Taiwan's government, lacking an international vision and conceptual thinking, has yet to devise a global talent strategy. National Taiwan University economics professor Chen Tain-jy, who served as the country's economic planning and development chief from 2008 to 2009, observes that Taiwan's talent development policies do not have clear objectives. Over the past 10 years, he says, the country's manpower policy has simply followed the lead of the Council of Labor Affairs (renamed the Ministry of Labor earlier this year) and focused on reducing unemployment and protecting the jobs of domestic workers.

Academia suffers from the same malaise. University presidents almost inevitably discuss the "internationalization of talent" when they hold their annual meeting, without agreeing on a solution.

"The most important factor in securing international talent is not getting foreign students to study here but rather keeping them here after they graduate. We've gone a lot of years without a breakthrough (in this area)," laments Perng Tsong-ping, a chair professor at National Tsing Hua University.

At a gathering of past and present MIT and Harvard students from Taiwan in April, almost all of those still in school had the same answer when asked whether they would return to Taiwan after graduating.

Instead of saying they "will not return home," the vast majority said they "are unable to return home." This subtle difference in phrasing reveals the longing that many Taiwanese students genuinely feel for their home country.

"I'm really sad when I think why I won't go back. From the time I was young, I attended public schools and then National Taiwan University, with my tuition paid for at taxpayer expense. Yet in the end I can't do what I should be doing. Why is the talent we cultivate unable to put their abilities to full use at home?" wondered Ben Tsai, who got a degree in electrical engineering from National Taiwan University (NTU) and is now studying in the United States.

Tsai's heartfelt response contains both the emotion and distress felt by many Taiwanese students abroad. The key to their dilemma is not just money, but also the need for the proper stage to showcase their talents. There are those who disagree with that sentiment, however, arguing that Taiwanese youth have not built a strong enough sense of identification with their country and lack a sense of responsibility to it.

Rebuilding the Talent Pool

Taiwan once had a rich pool of talent that has been gradually eroded and may even be in danger of disappearing.

Chen Chao-ming, a chair professor in Shih Chien University's Department of Applied Foreign Languages and a longtime advocate of internationalized education, says Taiwan needs to have more ambition to reach higher and become elite. "Becoming elite," he explains, does not necessarily mean working or studying abroad, but rather having every individual and company set their goals a little higher.

Morris Chang, the chairman of the world's largest contract chip maker Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC), believes there are no quick fixes.

"The talent issue needs at least a generation to solve. If it's not dealt with now, the next generation will face the same problem," Chang said at the CommonWealth Economic Forum in January 2014.

He suggested that Taiwan should selectively open its doors to the professionals it needs while at the same time cultivating its own talent, starting with the education system.

Taiwanese society may need one or two decades of steady effort to stand tall and develop its own stage on which its top minds can shine, a process which will not be without its costs. But Taiwan needs to think more boldly and imaginatively about its looming talent deficit and identify systematic strategies that can effectively create the talent pool needed to remain competitive in the future.

Translated from the Chinese by Luke Sabatier