Cross-strait Youth Culture

The Post-90 Generation

Source:cw

The new generation of Taiwanese and Chinese youngsters born in the 1990s differs from any other that preceded it. How will they change the future on both sides of the Strait?

Views

The Post-90 Generation

By Sherry LeeFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 512 )

Who are they? They are the privileged ones in an aging society, nurtured in an environment with a wealth of resources, but they face a future of relative deprivation.

Angry, idealistic yet practical, self-centered, dismissive of authority and uncompromising, divided and diverse, this group more resolutely stands up for what it wants. Possessing more explosive drive than previous generations, they are intent upon actualizing their aspiration, and are having a profound impact on both Taiwanese and Chinese societies.

How will this young generation, as yet incomprehensible to adults and misunderstood by those in power, rewrite the era in which we live?

This group of people born in the 1990s is known throughout China as the "Post-90 Generation." CommonWealth Magazine sent five teams of journalists around both Taiwan and China to investigate and interview these young adults in depth, lifting the veil on the new breed of ethnic Chinese people that will shape the face of the future.

There were 3.08 million people born in Taiwan and more than 180 million born in China during the 1990s. They are as closely aligned as any generation of people across the Taiwan Strait in the past 60 years.

Strengthening the narrowing gap between young Taiwanese and Chinese are burgeoning education ties. Taiwan opened its universities to full-time Chinese students for the first time last year, attracting nearly 2,000 Chinese nationals. Another 22,000 Chinese have come to Taiwan as short-term exchange students over the past five years. Similarly, 12,000 Taiwanese students have earned degrees at Chinese universities over the past decade.

They have learned and worked together and closely observed each other, not only as potential competitors but as cooperative partners, embracing broader contacts than ever before. Whether Taiwanese or Chinese, this young generation listens to Jay Chou and girl band S.H.E., watches the variety show "Mr. Kong & Ms. Hsi" and the drama series "Empresses in the Palace," and signs up with both Facebook and the Chinese social networking service Renren.

They all enjoy touring the island on the cheap, carrying their backpacks, reveling in their incredible mobility through their cell phones, the Internet, and convenient transportation links.

The Best of Times, the Worst of Times

Understanding this Post-90 Generation requires an understanding of the plight they face. They grew up in a relatively prosperous era and were coddled by their families within an aging society, only to awaken to one of the worst economic environments ever.

Taiwan's youngest generation grew up after the martial law period while China's was spared the upheaval of the Tiananmen Square massacre, and both have enjoyed eras of only limited political tensions as children. Economically, they were born into China's first and Taiwan's second middle-class generation, and they have enjoyed the benefit of more open parents and relatively equal parent-child relationships.

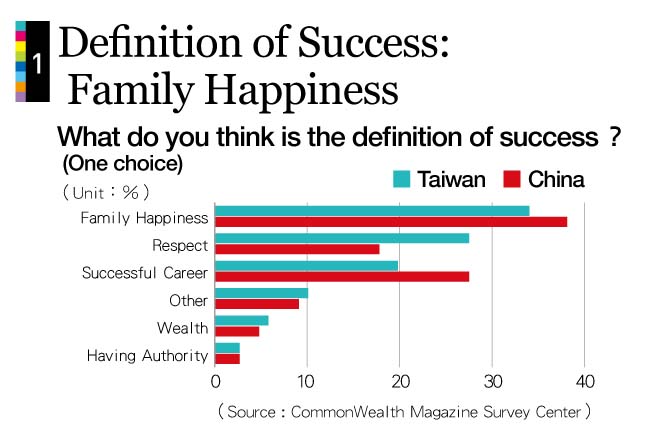

A survey of Post-90 university students conducted by Commonwealth Magazine found that their values differ considerably from the previous generation's emphasis on getting ahead and working hard to make money. Respondents believed that "the definition of success is familial happiness." (Table 1)

Those values may be colored by this generation's upbringing, having being raised in a period of unprecedented family wealth but now facing the worst economic environment in 20 years.

China's economy is no longer growing at breakneck speed, and Taiwan's may grow at a pace of just 1 percent this year. Both countries face major economic barriers that could be difficult to overcome.

Among them, the explosion in university graduates in the region has exacerbated youth unemployment to levels not seen by previous generations.

The jobless rate for new graduates from China's top 100 universities last year was 9 percent, twice China's overall unemployment rate. Taiwan's fresh graduates not only entered a job market where 13 percent of those in the 20-24 age bracket did not have work. On both sides of the Taiwan Strait, young people also had to cope with spiraling housing prices.

The Post-90 Generation has also been forced to accept an unenviable social status and finds itself on the wrong end of a forbidding salary structure.

When CommonWealth Magazine reporters asked students at National Taiwan University in Taipei and Renmin University of China in Beijing what their expected starting salaries were, the answers were surprisingly similar. Renmin University students said "5,000 renminbi" (about NT$23,300); Taiwanese students said "NT$25,000."

This generation appears stuck in an era of a rapidly widening rich-poor divide, especially in China, where many believe young people face an unfair competitive environment in which family connections are far more important than ability when it comes to getting ahead.

"They are the do-or-die generation. If they don't work hard, they will be left behind by the times," says Lio Mon-chi, an economics professor at National Sun Yat-sen University and longtime observer of generational change.

The First Generation Raised on the Internet

This group of teenagers and young adults also represents the first generation born with the Internet etched into its DNA.

To previous generations, the Internet serves merely as a tool, but to these young upstarts, the Internet is life itself. Forming the biggest demographic block in the Internet world, they learn on Google, get entertained on YouTube, and connect with their friends on Facebook.

Of Taiwan's 13 million Facebook users, roughly 5 million are 24 or younger. Similarly, a third of the 300 million Chinese who use Sina Weibo, China's biggest microblogging service, are also 24 or under.

The Internet has given this young generation "the opportunity to walk with kings," says Chinese entrepreneur Ma Jiajia, explaining that by registering as a fan of a celebrity, people can post messages or responses and interact with their idols. Many others use the network to boldly promote themselves professionally, sometimes scoring a prized interview with a foreign company.

National Cheng Kung University senior Chang Chih-ling used the Internet and the power of images to aggressively promote a social movement and build her own brand.

Chang truly felt the power of the Internet during Taiwan's presidential election in January. Only 21 at the time, she was one of many eligible to cast their first ballot. She noticed, however, that many students were unable to return home to vote (Taiwan does not yet have absentee voting) because they were busy with finals and decided to launch a movement to reclaim these young voters' civil rights.

A video camera in hand, she followed a classmate returning home to Hualian and produced a 1 minute 40 second video that encouraged the 300,000 people eligible to cast their ballot for the first time to go home and vote. Not long after it was posted on Facebook, the video received more than 100,000 hits and garnered coverage from the mainstream media.

Different Competitive Characters

The Post-90 Generation has similar family environments in Taiwan and China, but the two countries' divergent political and social soils have yielded different flowers, as revealed in extended CommonWealth Magazine interviews and a wide-reaching survey.

The magazine's reporters interviewed in depth more than 100 Taiwanese and Chinese students in both Taiwan and China, and surveyed another 2,000 students, generating a number of findings worth noting.

First, elite students from both sides of the Taiwan Strait agreed that Chinese students were far more dedicated to their studies than their Taiwanese counterparts. "They really give it everything," said one NTU student describing Chinese exchange students at the school.

Luo Mian, an exchange student from Peking University studying political science at NTU, says his Chinese peers show "excessive diligence and self-discipline."

"China has a big population and social values are rather uniform, so people study and work like crazy," Luo says.

Post-90 Taiwanese find themselves with complicated feelings when assessing their Chinese counterparts. Though more interaction and understanding exists between students from the two countries than ever before, one scholar observes that the China known to young Taiwanese is "a rich neighbor full of aggression." These students are "anti-China" and "anti-corporatism," explaining why they have been so opposed to a conglomerate perceived as favorable to China (the Want Want China Times Group) acquiring the Taiwan units of Hong Kong-based Next Media Group.

At the same time, China's Post-90 Generation has a common competitive consciousness and a sense of crisis.

Taiwanese writer Lee Cheng-Liang, a longtime observer of China's younger generation and a former communications professor at Tianjin Nankai University, says every Chinese student must write an essay on the subject "Falling Behind Means Defeat," instilling a sense of competitiveness across generations.

China's intensely competitive environment has left its young people wise to the ways of the world and decidedly utilitarian; Taiwanese students in contrast are generally more relaxed and have much more time for self-exploration.

The CommonWealth Magazine survey found that Taiwanese students saw themselves as being less market competitive than their counterparts in China, Japan, Singapore and Hong Kong, but Chinese students were far more confident of their competitive credentials. (Table 2)

Older generations may explain the relatively relaxed approach of Taiwan's Post-90 Generation as "lacking competitive consciousness," but is that really a fair assessment?

Under a corrugated steel roof in Guantian District in Tainan, young people are crowded around stacked cartons full of oranges. Chen Wei-cheng, a senior at Tainan National University of the Arts with fashionably spiked hair, discussed his level of competitiveness.

"I'm increasingly conscious of asking when I do something how much I'll learn from it and how challenging it is," says the Kaohsiung native. Professing not to be worried about his future salary, Chen intends to stay in Tainan after graduating and use his design skills to contribute to community building.

"As long as you work hard and dedicate yourself, things may be different one day," he says.

The Soft Power of Democratic Culture

While Chinese students clearly have a stronger competitive consciousness than their Taiwanese peers, Taiwanese students have irreplaceable advantages of their own.

China's Post-90 Generation was born after the Tiananmen Square Massacre, but the country's one-party monopoly still has a profound impact on culture through the education system. Though this younger generation generally believes in universal values, many university students in China have still unabashedly applied with their professors to join the Communist Party, largely for the purpose of gaining employment at state-run or central-government enterprises, or to become civil servants.

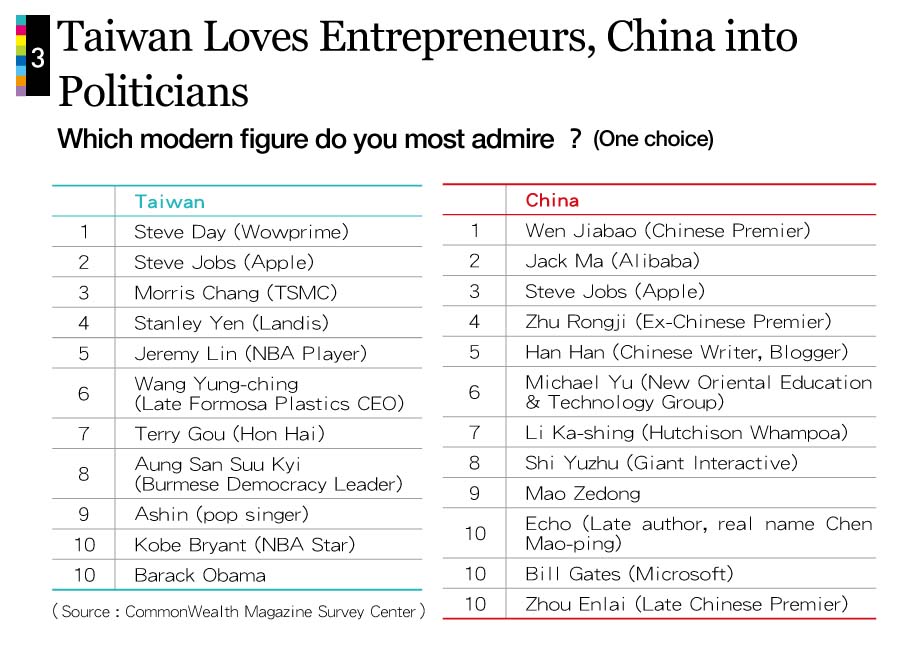

"There is only an upside to becoming a party member. There's no downside. Party members can travel abroad," says one sophomore at an elite university, fully exposing the self-interested nature of China's Post-90 Generation. (Talbe 3)

In contrast, Taiwan's Post-90 youths seems far more altruistic, with a much greater sense of community.

Born after the end of martial law, they are Taiwan's first generation with no memories of state repression and are free of psychological pressure to engage in self-censorship. Over the past year, they have collectively launched movements against the planned Kuokuang petrochemical complex, the expansion of the Central Taiwan Science Park in Jhanghua County, and the beachfront Meiliwan Resort Hotel in Taidong County, all on environmental grounds. Many student dissent groups and publications have resurfaced, seemingly reviving the dynamism of student movements seen at the end of the martial law period.

"Democracy salons" and volunteer activities on campuses and in Taiwanese society have grown in frequency, and these seeds of Taiwanese culture are rapidly influencing some of the elite of China's Post-90 Generation.

Among them, Renmin University student Zhou Yufei, who spent time as an exchange student at National Tsing Hua University in Hsinchu, has transplanted Taiwan's "democracy salon" culture at Renmin University, creating a "literati salon" at which intellectuals from both Taiwan and China discuss history and democracy.

In Wudaokou, an area in northeastern Beijing popular with students, a number of student-founded salons have already sprouted up, operating under the radar in apartments in high-rise residential buildings. On weekends, students pack into cramped three-room apartments to contemplate different topics and occasionally watch independent films, with discussions led by experts. The conversations even touch on such sensitive subjects as the 1989 Beijing student movement and Tibetan independence.

We Are the Future

The Post-90 Generation is already having an effect in both Taiwan and China, and exhibits a greater level of diversity than its predecessors.

"Every member of the Post-90 Generation is a bomb that can be easily set off," says a student named Ma Wei who graduated from Communication University of China this year.

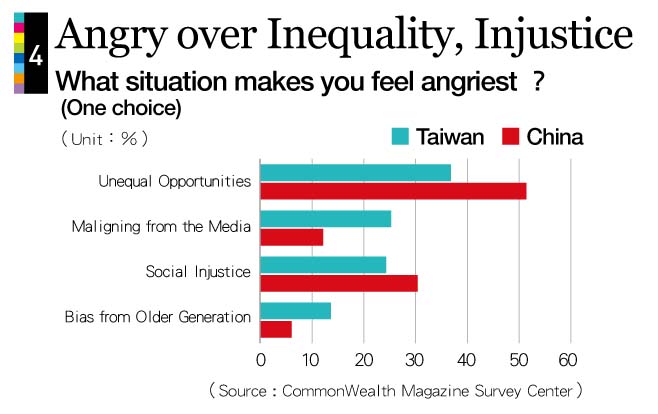

Ma, who is in the process of starting his own business, has been identified by Beijing-based Caijing Magazine as an up-and-coming entrepreneur. Comparing his generation with the one born in the decade before, Ma describes the Post-90 Generation as having many grievances but lacking the ability to take action to redress them, unlike his peer group, which is free of taboos but possesses "explosive drive." (Table 4)

Rwei-ren Wu, an assistant research fellow at Academia Sinica's Institute of Taiwan History, professes deep respect for this new generation, saying, "They have given renewed power to student movements that had long been reduced to ashes."

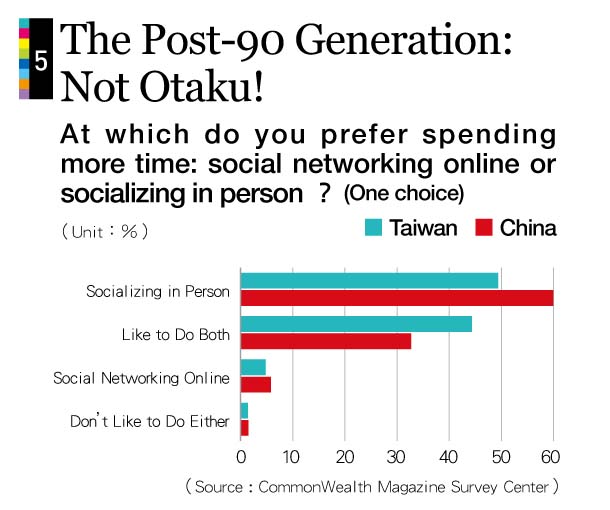

The Post-90 Generation's message is loud and clear: "Like it or not, we are the future. We may lose the battle before us, but we will win in the long run." (Table 5)

Previous generations are now duty-bound to figure out how to direct the eruptions of this "explosive generation" in a more positive direction. They will have to realize that what these young upstarts need is greater understanding, patience, opportunity, the courage to pursue their dreams, respect as equals, and a bigger stage to speak their minds.

Translated from the Chinese by Luke Sabatier

About the Survey

The CommonWealth Magazine Post-90 Generation Survey was conducted from Oct. 31 to Nov. 23 and targeted college and university juniors and seniors born after 1990. A total of 1,906 valid questionnaires were collected.

In Taiwan, 2,689 questionnaires were distributed based on a stratified proportional sampling method to students in 62 departments at 12 schools participating in the "Aim for the Top University Project." A total of 1,205 valid questionnaires were returned. In China, the survey was coordinated by Renmin University professor Zhou Tingrui. Questionnaires were distributed to universities in 24 provinces and administrative districts, including major institutions such as Peking University, Nanjing University, Wuhan University, Hangzhou University, Sun Yat-sen University (in Guangzhou), and Renmin University. A total of 701 valid questionnaires were returned.