Higher Education

Taiwan's Stray PhDs

Source:cw

Taiwanese officials warn of a looming talent gap, yet Taiwan boasts a talent pool of nearly one million people with advance degrees. After studying for more than 20 years, why are they facing such difficulties finding decent jobs?

Views

Taiwan's Stray PhDs

By Rebecca LinFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 507 )

Clad in a dark business suit and lugging a laptop and a briefcase over his shoulder, he has just arrived at the high-speed railway station, but is already drenched in sweat. He looks like a traveling salesman.

Yet the only product that he is trying to peddle is himself. The briefcase holds nothing but a bulky book, his doctoral thesis. Lin Kai-min (a pseudonym) holds a doctorate in engineering from National Tsing Hua University, one of Taiwan's leading universities. Yet over the past 18 months the fresh PhD has sent out almost 60 job applications to universities across the island, with little or no avail.

"Each university wants you to prepare a resume and CV. These must be photocopied, bound and sent by mail," he explains. His efforts yielded seven or eight invitations for an interview, a shooting average of 15 percent. "Each time I was invited for an interview I was very happy, because it meant that I had made it into the top six or eight among more than 100 applicants."

Several years ago, a new phrase emerged in Taiwanese jargon: liulang jiaoshi, or "stray teacher," to describe the growing trend of people with education degrees who could not find employment. Then, a further refinement of the term surfaced around 2006: liulang boshi, or "stray PhD." Today, a Google search yields nearly a million hits in an instant.

These highly skilled and qualified people with more than 20 years of education under their belt are looking for teaching jobs all over the place, or they drift from university to university making a living with several concurrent part-time teaching jobs at different schools.

A survey by the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics found that 4.5 percent of PhD graduates are still looking for jobs or are unemployed one year after graduation. Joblessness among PhD graduates is a severe problem – their unemployment rate is even higher than for senior high school graduates.

Jobless Academics Forced to Look Elsewhere

Despite the oversupply in PhD graduates, National Science Council minister Cyrus Chu warned in August that Taiwan is heading toward an imminent "talent gap," predicting that the island would "die a painful death" in competition with other countries.

How could it be that Taiwan faces a talent gap, given that Taiwanese graduate schools continue to churn out high numbers of master and PhD graduates? Why is Taiwan's competitiveness declining even though more citizens than ever before have received a higher education?

One of the reasons is that Taiwan's PhD holders are being forced to move abroad.

Let's return to Lin, the luckless job-hunting doctor of engineering. Just before his interview with CommonWealth Magazine, Lin went to a prestigious university in China to apply for a teaching position. Within two weeks he got a positive answer.

"Taiwan doesn't lack talent, it lacks a stage. Our only choice is to look for a stage elsewhere," remarks Lin, his frustration hardly disguised. A job in Taiwan remains at the top of Lin's wish list, but after his fruitless, lengthy quest for a university position, he has resigned himself to going abroad.

"If I remain in Taiwan, I won't be able to find a teaching position at a national university. If I work at a private university, I won't have any job security, because it might close down three years down the road," Lin explains.

The Chinese university department where Lin will teach has already attracted three other professors or assistant professors from Taiwan.

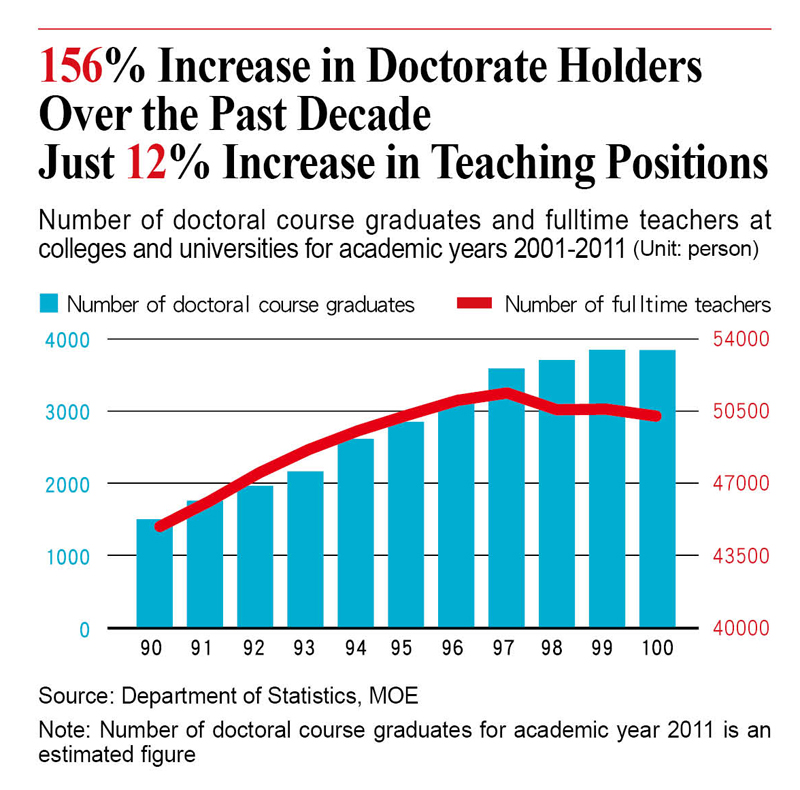

Although the number of graduate school graduates keeps swelling, job opportunities in academia are few and far between. Over the past decade the average number of PhDs graduating from Taiwan's 163 universities per year has more than doubled from around 1,500 to more than 3,800. (See Table)

Currently, Taiwan has nearly one million citizens with a graduate school degree, while another 220,000 are currently enrolled in doctoral or master's programs.

The problem is that the pace of growth in full-time teaching positions at colleges and universities is lagging far behind the growth rate for PhD graduates. Between 2001 and 2011 college and university faculty increased from 44,000 to 50,000 positions, which amounts to a 12.5 percent increase in the academic workforce. Securing a job in academia has become all the more difficult as the number of PhD degree holders by far outstrips job opportunities.

A Preference for Academia

Still, Taiwan's PhD graduates are particularly inclined toward serving as teachers. Ni Chou-hwa, a division chief at the Ministry of Education's Department of Higher Education, observes that 70 percent of Taiwan's PhD graduates pursue academic careers, while that ratio stands at just over 40 percent in the United States.

Another reason why PhD graduates have difficulties finding a job is that they are comparatively old when starting their professional careers and that they have unrealistic expectations. "Everyone goes into academia because there is no alternative. After finishing doctoral studies, you are most likely older than 35. Jobs that are physically demanding or require a younger age are all out of the question," notes Chen Hui-min, assistant professor at the Department of Sociology of National Taiwan University, in highlighting the difficulties of landing a job in the private sector. Chen was hired by her university this summer on a limited one-year contract, three years after obtaining her doctorate.

Chao Chung-chi, who has earned a doctorate in political science from National Taiwan University, also once attempted a career shift, but failed. Chao was interested in working for a non-governmental organization or a news outlet. People in executive positions in these fields, from secretary general to regional manager, are all around forty years old. Chao squarely looked at what he had to offer: he had academic training, but no experience and seemed clearly too old to work as an assistant.

Of course, another key reason that makes finding a job elusive is that PhD graduates often can't meet an essential requirement for private sector jobs – capability.

Taiwan's doctoral students are trained to be "academic workers." Chu Chien (pseudonym), who earned an engineering doctorate from a prestigious university in Taiwan, recalls that he was told at university that it was important to do good research and then write papers on it.

"But in Taiwan how to write papers is more important than how to do research," he complains. The research output of local universities is evaluated based on their number of publications in the Science Citation Index (SCI) and other international publication indices. As a result, research that can be written up as a paper is favored over innovative research. "The schools demand two SCI papers, so all you do is try to meet that requirement without giving thought to whether your research actually contributes to industry," Chu admits. Under pressure to collect points with regard to research output, the gap between academic research and the real world continues to grow.

"I spent seven years being trained, but as it turns out society does not need what I learned. I can't find my footing in society, so what should I do?" asks a PhD graduate from National Taiwan University accusingly. He feels that he has no other choice but to continue looking for a teaching job in academia.

A New Mindset, a New Path

Some doctorate holders have begun to change direction, embarking on new career paths.

During the summer break, Chen, the contract assistant professor, took her students on a trip to central and southern Taiwan to talk with local farmers for a better understanding of life in rural areas.

"I hope that my students are able to care about society, that they develop some new ideas with regard to their future lives," she says. "I don't want them to become as old as me before they start to think about this." She has also been trying to apply some imagination to her own career, collaborating with a publishing house in rewriting sociology papers for the general reader, in the hope of opening up a dialogue with society.

Chao, the doctor of political science, for his part, is still toying with the idea of looking for a teaching position at a university in China or Thailand, and he is busy publishing academic papers. But he has also begun to consider a more fundamental problem, asking himself: "What if my job search doesn't go well? What would I like and want to do most?" Chao likes to travel. Therefore, he took tour guide license exams in March for English and Chinese. He believes that more and more people in Taiwan are interested in having an in-depth travel experience. Chou thinks his educational background and personal interest in the arts could be selling points in the travel business.

Banning Retired Professors from Blocking Jobs

Faced with the glut in PhD graduates, some experts also demand systemic reform. For the past two years Chou Ping, dean of the Institute of Sociology at Nanhua University, has been writing articles demanding legal regulations on "double income professors." Chou wants persons who have retired from public office or national universities to be banned from taking paid teaching jobs at private universities, to prevent them from collecting a salary on top of their government-paid retirement pension.

According to statistics from the Ministry of Education, in 2010 a total of 1,351 retired government officials went on to accept a second position in higher education, 38 as university presidents, and 1,247 as professors or associate professors.

"If these dual-income professors retire, the oversupply in PhD degree holders could be absorbed at least partly," predicts Lee Wai-ting, assistant professor at National United University's Institute of Information and Society.

National Science Council vice minister Ho Cheng-hong, who obtained his PhD degree in France, believes that the Ministry of Education should take advantage of market forces and plan for universities to develop different specializations, allowing them to cultivate distinct profiles.

Even more important is that macroeconomic controls be put in place with regard to enrollment in doctoral programs, based on a national roadmap. National development, industry structure and talent cultivation go hand in hand. "All the agencies – the Council for Economic Planning and Development, the Ministry of Economic Affairs, the Council of Labor Affairs, and the Ministry of Education – need to sit down and do a good job talking with one another," urges Lee Wai-ting.

Translated from the Chinese by Susanne Ganz