Taiwan's Unfair Tax System: Helping the Rich Get Richer

Source:Shutterstock

NT$17 trillion in new wealth was created in Taiwan's equity and property markets from 2006 to 2010, but very little of it was taxed, a not-so-subtle indication of how far Taiwan's tax system has gone awry.

Views

Taiwan's Unfair Tax System: Helping the Rich Get Richer

By Hsiang-yi ChangFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 506 )

Jim Huang is 35 years old, a member of the third generation of a powerful political family in Taiwan. He does not have a job, but he's doing just fine.

In Taiwan, he lives in a 660 square-meter luxury apartment on ritzy Renai Rd. that he inherited from his father, and he also owns property in Los Angeles, Shanghai and Germany.

Through overseas trusts, Huang also holds stocks in the United States, Hong Kong and Taiwan worth more than NT$1 billion. With the help of two private banking advisers and their use of hedging techniques in the equity and futures markets, he earns a 6 percent return, or roughly NT$50 million a year, on his investments regardless of whether markets are bullish or bearish.

But Huang now faces a major decision. The United States Internal Revenue Service has aggressively pursued overseas assets of Americans in recent years to boost tax revenues, and Huang, who has American citizenship, is thinking about giving it up.

"The United States is cracking down hard. I've been thinking that it might be better to come back and be Taiwanese," says Huang, which is not his real name. "In any case, when you add it all up, the tax burden here is really low."

Because Huang's investments are channeled through a complicated array of overseas trusts and multilayer reinvestment structures, Taiwan's National Tax Administration has him classified as a "low-income household." In 2011, he paid less in taxes than his driver, just one example of how Taiwan has become a low-tax paradise for the wealthy.

Under Flawed Tax System, Debt Building Up

"The goal of the tax system is to have people pay taxes willingly and for the government to have peace of mind and feel justified when it taxes."

Those words were spoken by then Finance Minister Lee Sush-der in defense of three major tax reduction initiatives at the height of the financial crisis in late 2008. Lee's initiatives, which were later passed, lowered the corporate income tax rate from 25 percent to 17 percent, the maximum estate tax rate from 50 percent to 10 percent, and three marginal personal income tax rates by 1 percentage point. Three years later, the implication of Lee's memorable quote is clear. Taiwan is now one of the world's top low-taxation countries.

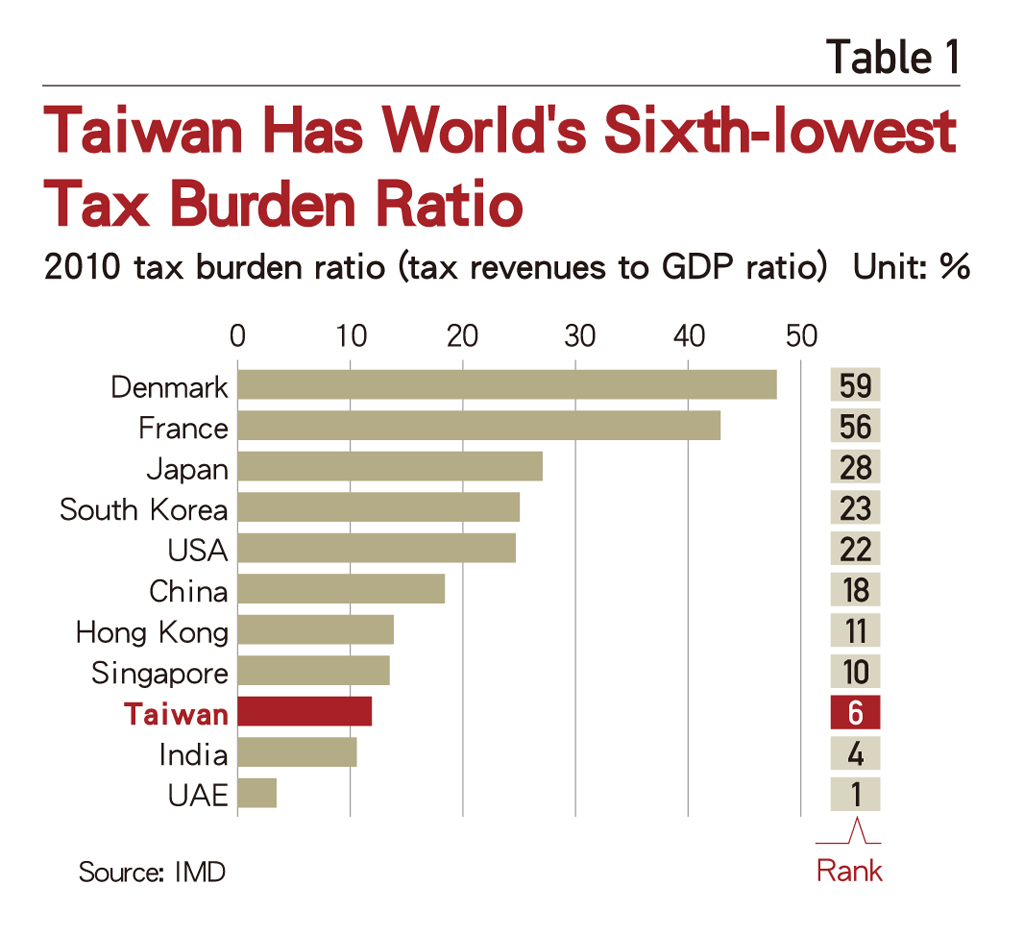

According to International Institute of Management Development (IMD) figures, Taiwan's ratio of tax revenues to GDP, known as the national tax burden ratio, fell from 20 percent in 1990 to 11.9 percent in 2010, the world's sixth lowest and even below those of Singapore (13.5 percent) and Hong Kong (13.9 percent), which are known as low-tax havens. (Table 1)

The few countries with lower tax burden ratios are either oil producing-countries (United Arab Emirates and Qatar) or developing countries with imperfect tax systems (Indonesia and India). Taiwan's effective personal income tax rate is only 5.96 percent, the 10th lowest in the world.

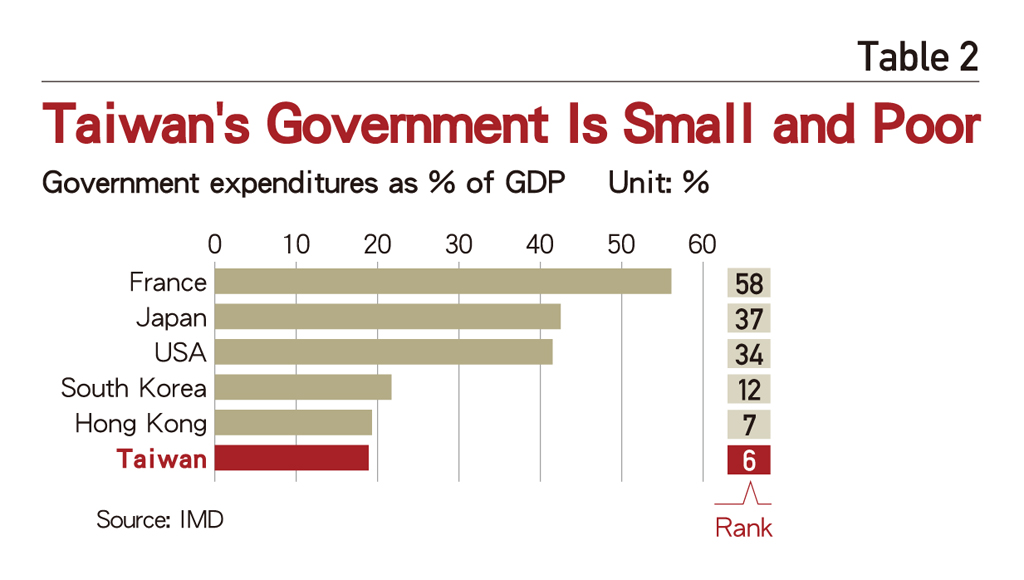

Such a low tax burden ratio has turned Taiwan's government into one of the world's poorest and smallest governments. Limited revenues have only heightened wrangling over the central government's budget for 2013, with Cabinet ministers squabbling constantly among themselves in front of Premier Sean Chen over budget priorities.

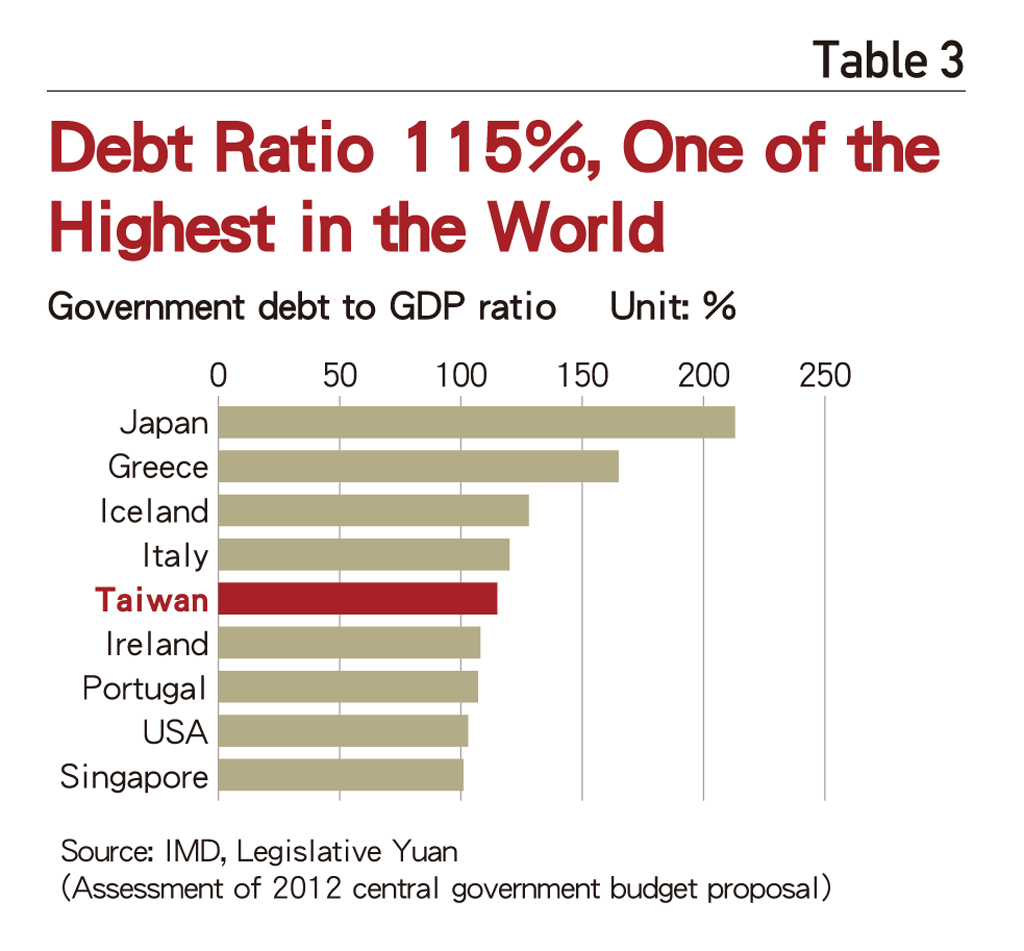

In 2010, the central government budget was 18.9 percent of GDP, the sixth lowest of any country around the globe. Even at that minimal level, expenditures have consistently outpaced revenues, leading to large deficits and the build-up of debt. Today, Taiwan's national debt totals NT$5.26 trillion and looms as a potential drag on the country's future. (Table 2, Table 3)

Tax revenues began falling precipitously as a percentage of GDP around 1990, when Taiwanese manufacturers began their exodus overseas in pursuit of lower labor rates. The government not only lost those companies' tax revenues, it also promoted tax breaks to keep domestic companies in Taiwan if they had not yet relocated abroad.

The decline in the tax burden ratio has prompted growing popular outrage over tax fairness issues. The wealthy have capitalized on widely accessible tax avoidance schemes to reduce their tax payments, leaving the middle class and salaried workers to shoulder the country's tax burden.

In other words, only the wealthy have felt the benefits of the low tax regime, while salaried workers who dole out the vast majority of taxes are coming under greater financial pressure and have developed a strong sense of deprivation.

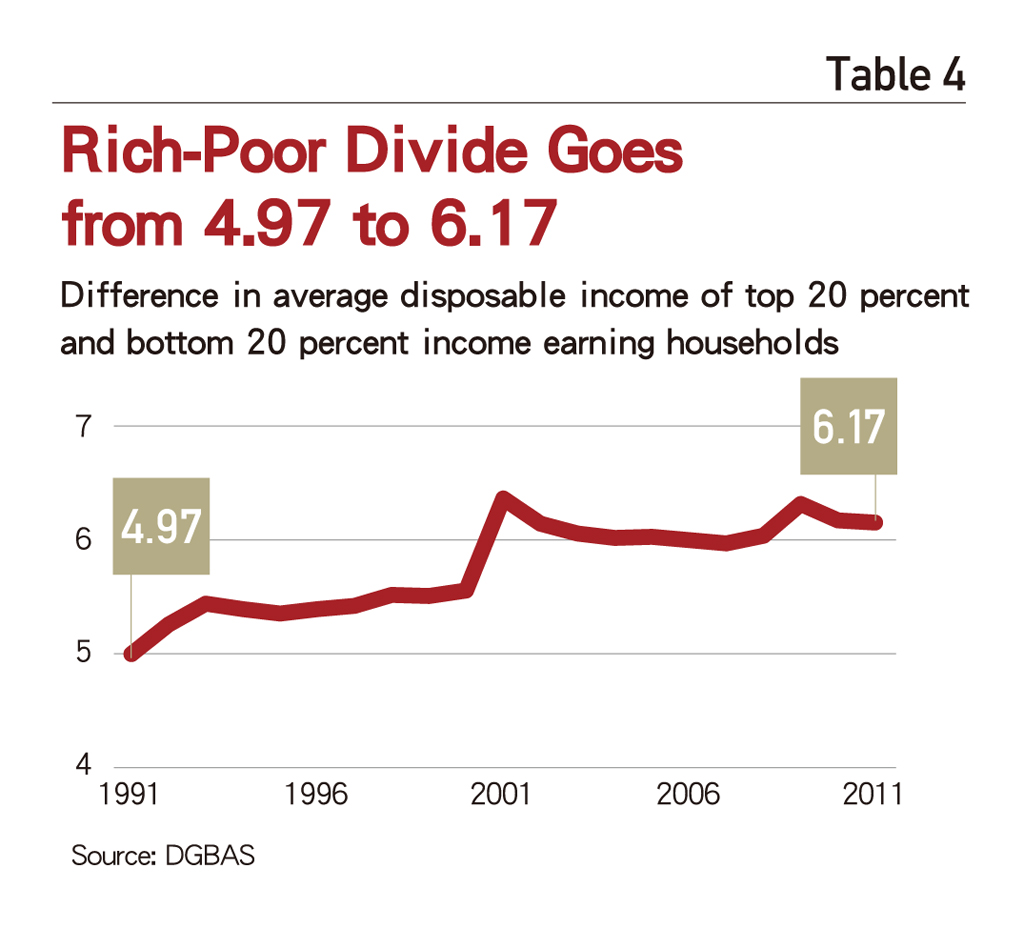

Governments invest tax revenues in developing their economies, building infrastructure and helping citizens in need of assistance. Because of these redistributive effects, progressive tax systems in theory should narrow the rich-poor divide. But in Taiwan, the opposite is occurring. (Table 4)

Black Hole #1: Regressive Tax Structure

A relatively young banker named Allen, who drives an SUV imported from Germany and wears a NT$2 million Swiss watch, went to play a round of golf recently with similarly aged customers and friends. Together, the group appeared to be "second-generation wealth" enjoying a leisurely outing.

In fact, of the other members in the fivesome, two were the sons of Taiwanese businessmen who head companies listed publicly in Hong Kong, one came from a big property-owning family in New Taipei, and the other was a big player in the stock market looking to set up a hedge fund in Hong Kong to invest in Asian equity markets.

They all live in Taiwan. Some didn't have name cards, a real rarity in Taiwan's business community, and those with name cards only listed their own name and the name of their family's company. But each member of the group annually earns tens of millions of Taiwan dollars in gifts, overseas income, and capital gains on property and stock transactions, and that's just a conservative estimate.

Worth over NT$100 Million, Maximum Tax Rate 20%

Each member of the group has a net worth of over NT$100 million, and they have something else in common: the only income tax they pay in Taiwan is on interest income from savings deposits and dividend income. The highest rate of tax any of them paid last year was 20 percent, the same marginal rate applied to middle class households with annual income of over NT$1.2 million.

On the other hand, Allen, a manager at a foreign bank, and his wife, who also works in the financial sector, earned over NT$10 million in salary and bonuses. But because every dollar they made was salary income that is automatically reported to the government, they had to "grudgingly pay more than NT$3 million in taxes to the government based on a marginal rate of 40 percent, making us a big taxpayer," Allen says. "But what can we do? Whether you make a high salary or low salary, working stiffs are working stiffs and not a penny can avoid (being taxed)."

Still not yet 40, Allen's annual salary of more than NT$7 million rates among the highest for salary earners. But even Allen, who has reached the elite echelon of the white-collar class by studying hard since he was young and climbing the corporate ladder based on merit, still sees himself as a victim of relative deprivation when faced with truly wealthy individuals who "use money to make money" and pay little in taxes.

"Many friends from my school days now point to me and say 'you wealthy people' and see me in a different light. How can I explain to them that under the current tax system, I'm also being treated unfairly," Allen says with a deep sigh. "I have nothing against the rich, but I've seen too many people with incomes tens of times higher than mine who pay less than a tenth of the taxes I do. It's hard not to get angry."

The great disparity between Allen's taxes and those of his very wealthy customers is a common phenomenon in Taiwan. To more closely analyze this growing problem, it is necessary to first define "the rich" to uncover wealth undetected by Taiwan's tax collection radar.

Black Hole #2: New Wealth, Barely Taxed

Because the government keeps financial information on the wealthy and how much they pay in taxes under wraps, analytical data on private banking customers may be the next best alternative to gauge the extent of "hidden wealth" held by Taiwan's wealthiest households.

According to the 2011 World Wealth Report published by Merrill Lynch Global Wealth Management and management consulting firm Capgemini, high net-worth individuals are defined as those having investable assets of US$1 million (about NT$30 million) or more, excluding their primary residence, collectibles, consumables and consumer durables.

Based on that definition, there are 96,000 high net-worth individuals in Taiwan. Their assets have grown by 30 percent over the past four years to NT$10 trillion, or roughly 10 percent of all the wealth in Taiwan.

So how much do these private banking customers pay in taxes? One executive at a foreign financial institution in Taiwan told CommonWealth Magazine: "According to our internal numbers, private banking customers pay about 8 to 10 percent of their income in taxes every year." If accurate, that number pales in comparison with the highest marginal personal income tax rate of 40 percent and even with the alternative minimum tax rate for individuals of 20 percent.

The latest national wealth statistics issued by the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS) on August 30 proved that Taiwan's tax system is growing increasingly disconnected from how wealth forms in the country.

"Making money with money" and "land equals wealth" are commonly heard sayings in Taiwan, and they have never resonated more than they do today. In the five years from 2006 to 2010, household wealth in Taiwan grew by NT$24.6 trillion, according to DGBAS figures. Of that, NT$16.6 trillion, or nearly 70 percent, resulted from capital gains on stock transactions, which are not taxed in Taiwan, and profits from property transactions, which are taxed at very low rates.

Black Hole #3: Equity, Property Almost Tax-free

Over the past 10 years, taxes collected on salary income have accounted for over half of all consolidated personal income tax revenues, while most of the rest has come from dividend income. In 2010 for example, Taiwan's salary earners contributed nearly NT$150 billion in taxes on their wages, about 55 percent of all personal income taxes. In contrast, income taxes on gains from asset transactions totaled less than NT$1.2 billion, about 0.44 percent of the total. (In fairness, local governments collected NT$73 billion in land value increment taxes, Taiwan's version of a capital gains tax on real estate that is not included in individual income taxes.)

More broadly, income taxes (personal plus corporate) have accounted for about 40 percent of all taxes collected in the country in recent years, while securities transaction taxes plus total land taxes (including the land value increment tax, Taiwan's version of the capital gains tax on property) has been only about 13-15 percent of the total. (Table 5)

Major stock investors in Taiwan have never had to pay taxes on capital gains on equities. And a new dual-track tax plan, advertised as a capital gains tax on profits from stock transactions, that takes effect on January 1, 2013 does little to change that. Anti-Poverty Alliance founder Chien Hsi-chieh has bashed the program as a "disfigurement" that completely deviates from a capital gains tax based on the "ability to pay" principle.

Instead, in the first two years of the measure, investors will have the option to pay what is essentially an additional stock transaction tax, and only if the stock market's benchmark index exceeds 8,500. Even after that, the tax will only apply to gains earned by investors who have traded more than NT$1 billion in shares in a single year or through trades on IPO shares.

In terms of gains on buying and selling property, Taiwan does have the land value increment tax, but it is also flawed. Taxes are collected not on actual transaction prices but on much lower government-assessed values. The system has resulted in profits from property speculation being completely out of proportion to the resulting tax liabilities.

Transactions of landmark luxury apartments in Taipei clearly demonstrate the absurdity of Taiwan's property tax system as it exists today.

NT$4 Million Tax on an NT$80 Million Capital Gain

"Treasure Palace price per ping soars above NT$2.7 million" screamed headlines of Taiwan's major newspapers in April, referring to the most expensive residential complex in the country. A real estate broker said the 164-ping (540-square-meter) unit (on the 17th floor of Building B) was sold by a well-known investor who had bought the apartment at the end of 2010 for about NT$2.2 million per ping.

If information on the transaction is accurate, the investor made NT$82 million on the sale. If NT$82 million were to be taxed as salary or dividend income, most of it would be taxed at the highest marginal rate of 40 percent, resulting in tax bill of close to NT$30 million.

The investor likely only paid a small fraction of that, however. Taipei Department of Land records show that the amount of land apportioned to the Treasure Palace unit was 25 pings and that the "current assessed land value" – assessed by the government for tax purposes – rose to NT$610,000 per ping over the two years the investor held the property.

On a profit that was in fact NT$82 million but assessed by the government at NT$15.25 million, the investor paid a land value increment tax of NT$3.05 million, an effective tax rate of 3.71 percent. Even when deed taxes and other fees are added, the investor's tax liability was still under NT$4 million, or lower than 5 percent, the lowest marginal rate on personal income taxes.

Capital gains on equities and property are not the only huge black hole in Taiwan's tax system. Tax liabilities on the holding or transfer of wealth are also extremely low.

"In the simplest terms, the cost of holding (property or securities) is low and gains on asset transactions are either tax-free or taxed at a low rate. All you can say is that Taiwan's wealthy, who use money to make money, are truly blessed!" laments Wang Jung-chang, the convener of the Alliance for Fair Tax Reform.

Getting Around Paying Taxes

Not only is the tax system backward and disconnected from wealth creation, but when it comes to actual tax collection, the government often does an inadequate job, and lacks a comprehensive set of measures to give its tax-collection efforts teeth. This has turned Taiwan into a low-tax paradise catering to the wealthy.

"You have to clearly categorize the rich or companies paying less in taxes into three distinct circumstances. There's 'tax saving,' where incentives are given to businesses or investors. The policies can be debated, but there's no debating its legality. Then there's 'tax evasion,' where people deliberately hide their income. This is criminal behavior, and there is no controversy about dealing with it. The most problematic category is 'tax avoidance.' The process seems legal but in effect reduces taxable income. Examples of this are widespread in Taiwan," says former finance minister Lin Chuan in an interview with CommonWealth Magazine.

During his run as finance minister from December 2002 to January 2006, Lin introduced an "alternative minimum tax" to bring income that previously went untaxed, such as overseas income, income from unlisted stocks, and gains on employee stock options, into the tax base.

"The idea was to have wealthy people who benefit from many tax breaks and have access to hedging options to at least pay some tax," Lin says.

In 2005, Lin went a step further. He tried to showcase the prevalence of tax avoidance and even spark a debate by publicly releasing a list of how much Taiwan's 40 top income earners actually paid in taxes. Even today, those numbers are eye-opening.

Among the 40 individuals, 15 paid effective tax rates of under 1 percent, and eight of them paid no taxes at all. Only six of the 40 paid taxes at the highest marginal rate.

Lin observes that seven years later, public opinion is more concerned about tax fairness than ever, but tax reform remains inadequate and tax avoidance and evasion continue unabated.

Tax Cuts: Fattening the Rich, Weakening the Country

Taiwan's unfair tax system has not only let the wealthy off the hook, it has also plunged the country's finances into dire straits.

Over the past four years, Taiwan's national debt has risen from NT$3.7 trillion to NT$5.26 trillion, a 40 percent increase. That translates to about NT$660,000 of debt per household, equal to a year's income for salary earning families.

"We can't wait any longer for a complete overhaul of the tax system," says Ulyos K.J. Maa, a partner at accounting firm KPMG Taiwan.

Since the global financial crisis in late 2008, Western countries and even China have all actively reformed their tax systems, broadening their tax bases by making overseas income and income on financial product and property transactions as taxable and also imposing wealth taxes. The United States is one of many countries, for example, aggressively trying to recover taxes on foreign assets held by U.S. citizens under the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act.

In Taiwan, however, there has been no comprehensive review of the country's tax system. Even the new capital gains tax on securities transactions, supported by 65 percent of Taiwanese citizens, caved in to pressure from vested interests and was so watered down that its impact will fall far short of the goals it was meant to achieve, such as narrowing the rich-poor divide.

Even worse, at a time when the government is facing serious financial shortfalls and the economy is slumping, some in the government are now advocating expanding tax rebates on exports as a remedy for the recent decline in Taiwan's exports, which fell year-on-year for the sixth consecutive month in August.

Others completely ignore that Taiwan already has some of the lowest tax rates in the world and push for further tax breaks, usually targeted at those who need them the least.

After Finance Minister Chang Sheng-ford suggested repealing the luxury tax barely a year after it took effect on June 1, 2011, two lawmakers on the Legislature's Finance Committee, Lo Ming-tsai and Lu Shiow-yen, more recently called for a reduction in the securities transaction tax – currently set at 0.3 percent – and the cancelation of the futures transaction tax to "save Taiwan's stock market."

Breaking the 'Tax Cut' Myth

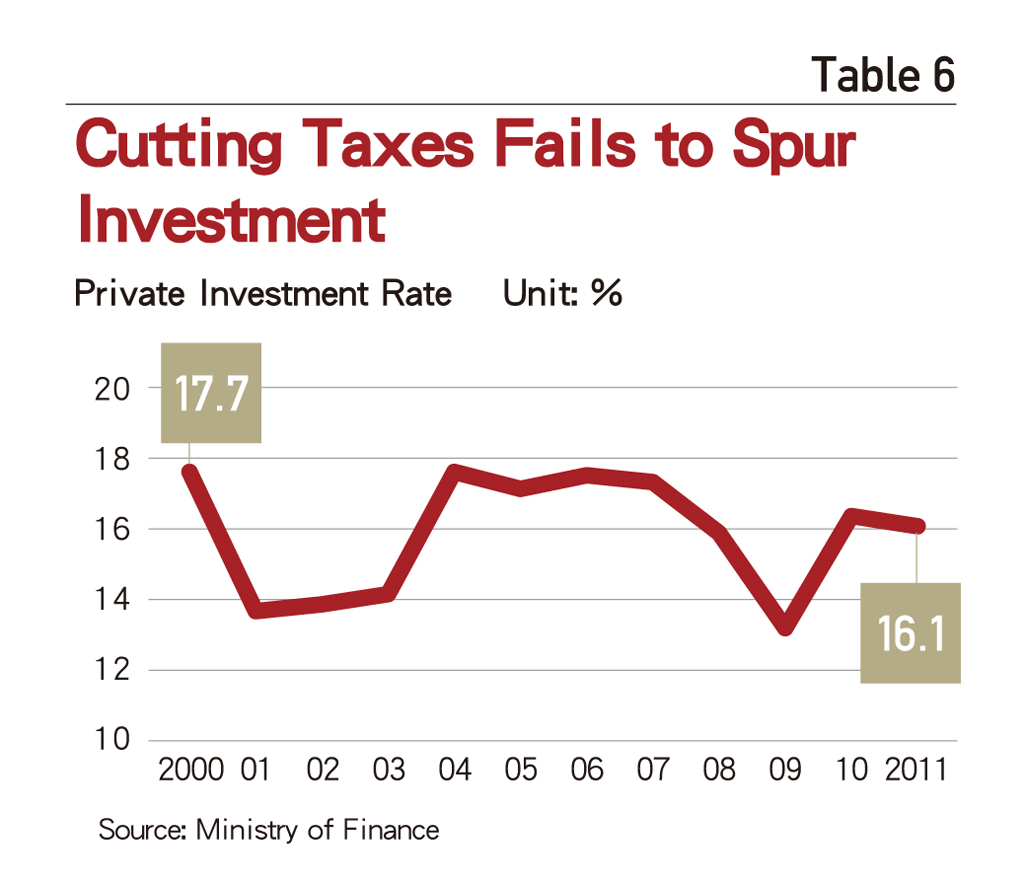

It almost seems that policymakers have blind faith that cutting taxes is a panacea that can solve any economic problem and spur increased investment. In reality, Taiwan has lowered tax rates aggressively in recent years, but the policy has not bolstered investment or lured capital from overseas Taiwanese businesses back home. (Table 6)

Clearly, cutting taxes has not convinced Taiwanese businesses operating in China or on other foreign shores to leave a little of their tax dollars for Taiwan.

Tung Chen-yuan, a professor with the Graduate Institute of Development Studies at National Chengchi University and a former deputy chairman of the Mainland Affairs Council, says that over the past 10 years, Taiwanese businesses in China have paid nearly NT$3 trillion to the Chinese government, roughly twice Taiwan's total annual tax haul.

"The idea that cutting taxes can rescue the economy is obviously not true," says former finance minister Lin. To improve Taiwan's unfair tax system, Lin argues, policymakers must abandon the myth of "tax competitiveness" – the lower the taxes, the more competitive an economy. The tax base and sources of revenue must be broadened before any debate over cutting taxes can be contemplated.

KMPG's Maa observes that since the global financial crisis, consumption has contracted and unemployment has risen. For both corporations and individuals, "most of those who still can earn money do it through capital (equity and property) transactions." Consequently, Taiwan's tax system can no longer remain stuck in the distant past when income was primarily derived through corporate revenues or individual wages.

There was a time when the first round of tax reform in Taiwan, led by economist Liu Ta-chung, who chaired the Commission on Tax and Tariff Reform from 1968 to 1970, created Asia's most advanced consolidated income tax system and financially supported the extension of compulsory education to junior high school.

There was also a time when Taiwan's finances were the soundest in the world. The central government's budget consistently ran a surplus during the 1970s and 1980s when the economy took off.

But following changes in the general environment and the popularity of the myth of cutting taxes to stimulate economic activity, Taiwan now lags behind international trends, and its "low but unfair" tax regime has clearly gone awry.

The only hope is that the government and the people will recognize the reality that "the government is poor, the people are poor, but the rich are very rich," and show the determination necessary to face up to the problem and find a solution.

Translated from the Chinese by Luke Sabatier