Curitiba

Brazil's Easiest City to Live In

Source:CW

At the Rio+20 Earth Summit in June, Curitiba won a Global Green City Award, and UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon called it a model of sustainable development. How has it won such acclaim?

Views

Brazil's Easiest City to Live In

By Jin ChenFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 502 )

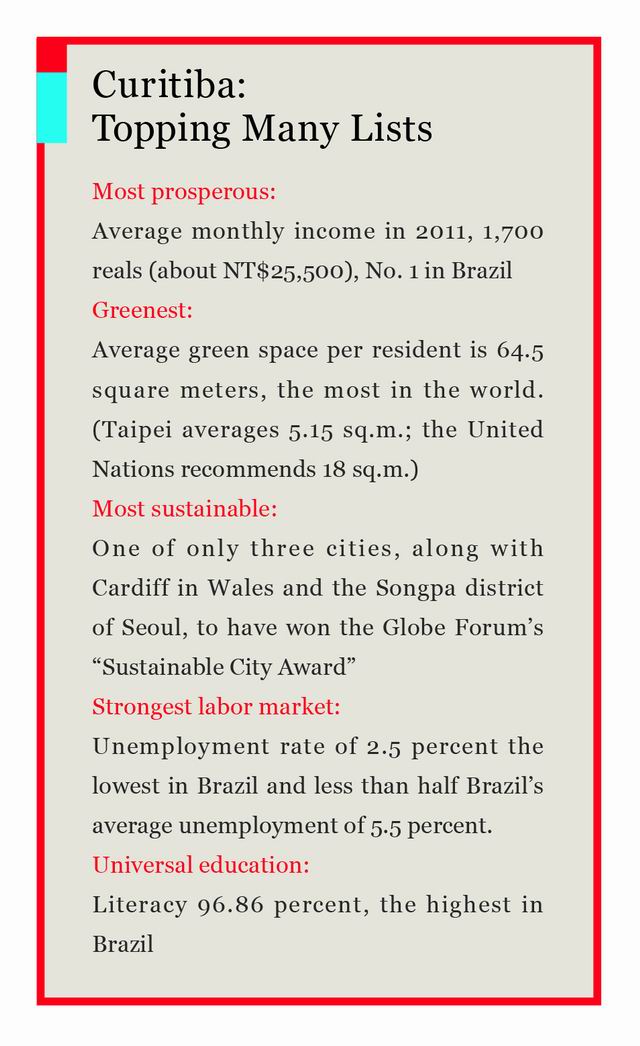

Curitiba is a true urban wonder, the rare city that has found an enduring balance between growth and sustainability. Brazil's eighth biggest city with a population of 1.75 million, it has set many benchmarks in its own country and the world.

It has the highest average monthly salary of any Brazilian city at 1,700 reals (about NT$25,500), and its unemployment rate of 2.5 percent is half the national average. (See Table)

It has earned acclaim for being people-friendly. Curitiba is neither Brazil's capital nor its biggest city, yet in 1990, it became one of the first municipalities recognized by the United Nations as among the world's most livable cities, along with Paris, Vancouver, Sydney and Rome.

It's amazingly green, with 64.5 square meters of green space per person, 13 times the amount seen in Taipei and four times the level recommended by the United Nations.

It's sustainable, winning the Globe Forum's "Sustainable City Award" in 2010, the second of only three cities to earn the honor.

Curitiba hasn't always been this way. Forty years ago, it was notorious for its high crime, poverty and unemployment rates, and drug peddling was rampant. In the 1970s, however, a group of passionate young people undertook an unorthodox urban revitalization plan that changed everything.

Their innovative approach was to set the city on the path of reform by first overhauling Curitiba's public transportation network and garbage disposal system.

The group's leader at the time was the city's mayor Jaime Lerner, who is now 75 and, despite a full head of gray hair, has as much vitality as ever. CommonWealth Magazine caught up with him and the man who inherited Lerner's legacy, incumbent mayor Luciano Ducci, to find out what makes Curitiba tick.

"A city's masters are its people. It is a city that writes the word 'people' in capital letters," says Ducci in defining Curitiba.

The city defies visitors' expectations of Brazil from the time they get off the plane. Located in the southern part of the country, over 300 kilometers southwest of Brazil's biggest city Sao Paulo, Curitiba sits on a plateau nearly 1,000 meters above sea level, far away from the beaches, sunlight, and passionate carnival atmosphere for which the country has become known. Delve into the city's streets and alleys, however, and one quickly discovers Curitiba has a real dynamic flow of its own.

Return Space to Nature

Towering trees rise from every corner, and parks are scattered everywhere, giving the city another word it emphasizes in capital letters: "green."

The city originally conceived the parks as its front line in preserving water and preventing flooding. At a time when Taipei was reclaiming its Liugong Canal to pave the way for bridges and big buildings, Curitiba chose to return space to nature, zoning riverside areas vulnerable to flooding as parks.

Local residents naturally came up with creative ways to use the green cityscape. "Green spaces have become venues bringing people together," said a consultant to the city's environmental bureau, Leny Toniolo. To him, the city is as alive as any human being.

At a high point on one of Curitiba's undulating roads is a scenic overlook offering a panoramic view of the city. The skyscrapers that dominate the skyline form an orderly matrix, interspersed among smaller residential buildings. Their height differences of several dozen meters clearly mark the locations of major thoroughfares.

The pattern did not simply occur haphazardly. It resulted from meticulous land planning.

The city deliberately allowed structures fronting its major avenues to have high floor space ratios (the ratio of the floor area of a building to the area of the plot of land it sits on) to encourage development, but capped the ratio at much lower levels in other parts of the city. By lining main arteries with tall buildings, the city was tacitly pushing commercial activity to converge in these areas and increase the incentive for people to use public transportation as their primary means to get around.

Designing policy based on diverse considerations is what makes Curitiba's integrated development strategy unique. But the city is best known for its mass transportation system. Many of Taipei's most advanced transportation initiatives in recent years, such as dedicated lanes for public buses, were inspired by the Curitiba experience.

At the time authorities in the Brazilian city were planning a transportation network, they decided against a subway system in favor of buses, for a very simple reason: a shortage of funds. Curitiba's annual budget is half that of Taipei's, and building a subway or light rail at a cost of nearly US$100 million per kilometer would have crowded out other essential infrastructure projects.

When public funds are tight, what can a city do? Raising taxes, issuing debt, or simply doing nothing – these are all options. But Curitiba evaluated a range of projects, and ultimately chose an overhaul of the public bus system as the starting point of its urban renewal campaign.

Bigger Daily Traffic Flow than Taipei

The city government made a deal with Volvo to set up a factory in the area and develop buses with two or even three sections able to carry up to 250 people at a time and with doors that opened up like a subway train. Today, the creative approach has spread around the world, with London, Sydney, and Bogota all using multi-section buses.

The city may have built its rapid transit bus system to save the cost of digging underground for a subway but still adopted the "station" concept and pre-boarding fare payment system common in rapid transit systems, and the dedicated lanes are unimpeded by signals or pedestrian crossings. The project proved inexpensive and quick to build, and it offered plenty of route flexibility and could be easily integrated with nearby suburban communities.

At peak commuting hours, bus platforms are packed, but the high frequency of the rapid transit bus system moves people quickly. The system serves an average of 2.3 million people per day, about 40 percent more than Taipei's MRT system.

In Curitiba, however, the concept of "mobility" in the context of city planning extends well beyond simply resolving transportation bottlenecks. It actually tailors the system to the main mobile actors – the people – who use it.

The extensive network of routes, barrier-free spaces between buses, platforms and streets (buses have ramps that extend out to the station platform when the doors open), and inexpensive fares have narrowed the distance between different segments of society.

Lower-income groups, which have the greatest need for low-cost transportation options, often live the farthest away from downtown areas. Calculating fares based on distance traveled, therefore, contributes little to narrowing the wealth gap.

To improve the mobility of poorer city residents, the bus system charges a single fare of 2.65 reals (about NT$39) for travel throughout the system and includes unlimited transfers. That means middle class residents who live closer to the city and have shorter commutes pay relatively more in transportation costs, in essence subsidizing lower-income residents. In its own small way, the system actively redistributes wealth.

Another creative idea advanced by Curitiba to help its poorer residents has been its Green Exchange program, held twice a month in each community, under which each household can get a kilogram of food for every four kilos of recyclable materials it collects and turns in. The program, which has become an important activity in villages in the area, encourages residents to recycle and at the same time offers additional support to low-income earners.

One other convenient service tied to the city's transportation network is Curitiba's public service center network.

The City as Turtle

Almost every transfer station along Curitiba's major transportation arteries includes a resident service center featuring 10 to 20 essential service providers, such as government agencies, public utilities, employment agencies and financial institutions. As a result, residents can take care of many of their daily errands before they get on or after they got off a bus.

If the city had not been people-oriented, it would never have designed such a simple but attentive system.

"A city is an organic framework incorporating life, work and leisure. Every element is closely tied together," says former mayor Lerner in explaining his core planning philosophy at the time. "It's like a turtle, living and working are all under one shell."

No matter how green or convenient a city is, however, without economic activity and businesses, it cannot survive.

Attracting companies and investment usually requires incentives and subsidies, and Curitiba is no exception. But its strategy is different regarding what kind of companies and investments it tries to attract.

"From the beginning, we set a firm policy of not welcoming 'chimney' industries," recalls Gilberto Jose de Camargo, the head of the Curitiba Development Agency. The policy came at the cost of losing many investment projects to other cities, but as de Camargo says, "we couldn't sell our souls."

In a city where "people" are the core value, a high quality of life has replaced financial and tax incentives as Curitiba's greatest selling point, enabling it to follow a development path of its own.

Swedish appliance maker Electrolux, known for its green products, has only five R&D centers around the world, and one of them, as hard as it may be to imagine, is in Curitiba. One of HSBC's global technology centers is also located there.

The world's biggest oil company Exxon Mobil Corporation has set up a business support center in the city to manage its global tanker truck fleet, and Bosch, Siemens and Wipro are among the multinationals that have built R&D centers, IT service centers or customer service centers there.

Curitiba's success in luring businesses even has the mayor of Brazil's economic capital, Sao Paulo, complaining of seeing its industries stolen away. Today, 80 percent of the city's working population is employed in the service sector, especially in the non-polluting, technology-heavy IT services sector.

Curitiba's tangible accomplishments demonstrate to the world that economic development and environmental preservation can co-exist and that surviving and living are not contradictory.

Kaohsiung native Chen Chin-liang has tried living in dozens of cities in search of his ideal home.

He has lived in different places for a month or two at a time and then moved if he wasn't satisfied. After settling briefly in big cities such as Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo and experiencing Paraguay, he chose Curitiba as the city where he wanted to live permanently.

"This place is a really comfortable place to live," Chen says in Taiwanese, wearing a genuine smile.

But the city's great living environment may also be its own worst enemy. By continuing to attract immigrants like Chen, Curitiba's population has grown steadily, stretching its vaunted transportation system to its limits.

At a peak commuting hour, public buses are backed up in a line three to four blocks long, waiting to pull into one of the city's tubular, clear-walled bus stations. What was once the paragon of mass transit efficiency can seemingly no longer handle the crowds.

"Curitiba is not a model," former mayor Lerner admits bluntly. The successful experience of the past does not guarantee the city will continue on the path to paradise, because it still faces many problems.

Fortunately, "Curitiba solves problems a little faster compared with other cities," says Ricardo Bindo, the planning director of the Institute for Research and Urban Planning of Curitiba.

And help may be on the way. Curitiba will break ground on a new subway system at the end of this year.

Wherever people want to get to is the direction in which the city wants to go. The Curitiba miracle, which began with public transportation as the catalyst of urban renewal and a determination to be people-oriented, still has many chapters left to write.

Translated from the Chinese by Luke Sabatier