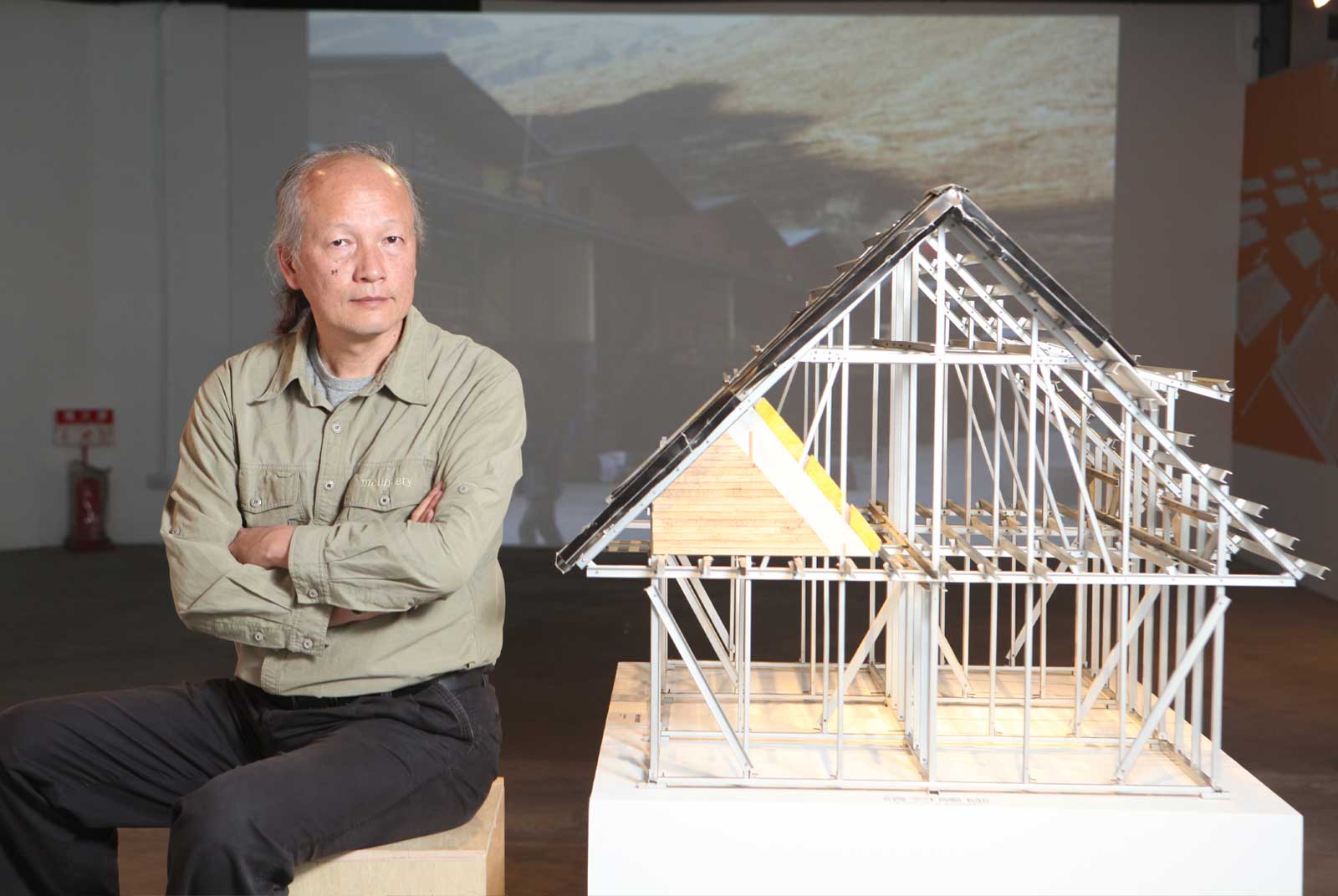

Fighting for Taiwan: Architect Hsieh Ying-chun

Bringing Affordable Shelter to the World

Source:CW

Taiwanese architect Hsieh Ying-chun has developed inexpensive, easy-to-build homes that have helped rebuild communities in Taiwan hit by disaster. He’s now hoping they can house refugees across the globe.

Views

Bringing Affordable Shelter to the World

By Rebecca LinFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 600 )

Is housing a commodity or is it a basic human right?

The buildings that Hsieh Ying-chun designs answer this fundamental question. In the wake of Typhoon Morakot, which hit Taiwan in August 2009, burying several villages in landslides and mudflows, the light steel structures developed by Hsieh and his team were used in the reconstruction work. More than 1,000 homes featuring high gable roofs were erected by members of the devastated communities in a concerted effort. With their cottage-like wooden houses, these post-Morakot communities in Laiji, an aboriginal village on Mt. Ali, Majia Farm in Pingtung County, Hualien and Kaohsiung resemble holiday resorts.

The cost of each home was only 60 percent of the reconstruction cost estimated by the government at the time.

The US$2,000 Miracle

The collaborative construction model emphasizes “participation” and “reasonable pricing,” quite the opposite of what most people connect with architecture. Hsieh is also exporting his model abroad. He tours the world to find suitable “soil” where his houses can “take root” and thrive.

Meanwhile, Hsieh’s team has left its mark in many countries, from China to the Philippines. Most recently they were hired by a non-governmental organization from Hong Kong to help rebuild villages in Nepal that had been destroyed in a massive earthquake in April 2015. Villagers worked alongside the volunteers jointly constructing houses. Each of the two-story homes had a living space of around 70 square meters and cost US$2,000 (about NT$60,000).

While Hsieh is an architect, he might be better described as a dreamer who envisages a fairer world—a utopia. “Modern people consider building to be consumer behavior; they pay a construction company to build [the house],” Hsieh says. Before designing homes for relief efforts, Hsieh built semiconductor factories for industrial clients in the Hsinchu Science Park. When participating in the reconstruction efforts after a devastating earthquake hit central Taiwan on September 21, 1999, Hsieh was surprised to see house building as part of the “productive” value-creating process in aboriginal villages. When members of a community help each other build their houses, life, production and culture are mutually connected. In the past, Taiwanese villagers also bought their construction materials themselves, hiring workers to assist them in building their own houses.

However, houses built with modern construction materials and based on modern esthetic standards become more and more like impregnable fortresses. As a result, they are cold in the winter and hot in the summer. Aboriginal housing or self-built traditional farmhouses, on the other hand, withstand earthquakes surprisingly well.

The collaborative home construction model that Hsieh promotes allows residents to assemble houses by themselves, utilizing local construction materials, regardless of the country or region.

The collaborative home construction model that Hsieh promotes allows residents to assemble houses by themselves, utilizing local construction materials, regardless of the country or region.

“Obviously this [quake-proof construction] has nothing to do with professional building skills,” remarks Hsieh in summing up his surprising findings. “The fact that the style of housing of about 70 percent of the world’s population has nothing to do with my profession forced me to think about how I could make a breakthrough,” Hsieh recalls.

Hsieh took the collaborative concept practiced in Taiwan’s aboriginal communities to other places by making the structures open to the spaces they occupy. In the wake of the September 21 earthquake, Hsieh and his team used Taiwan as their R&D base. While studying different construction materials, they discovered that light steel structures could be easily mass produced to a high-quality standard. At the same time, they could be easily assembled and offered the flexibility of an “open” flexible layout. No matter where the buildings were erected, their light steel frame could be complemented by local construction materials and techniques.

After they had completed around 300 homes in Taiwan, they began to promote the light steel structure dwellings in rural villages in China in 2004. Eventually they arrived at a model where Hsieh and his team only provided the design, the light steel structure and guidance during its assembly, while the local villagers carried out all the work themselves.

The resulting structures all look different depending on the location because the design leaves room for traditional styles. In Tibet, for instance, the houses were built with clay and straw walls. In Wenchuan County in China’s Sichuan Province, which was leveled by an earthquake in 2008, men and women from the Qiang ethnic minority built entire fortress villages with their own hands using local stone slabs and construction materials recovered from old houses.

The construction system that Hsieh and his team developed allows everyone, including men, women and the elderly, to join in the effort, since it keeps every step simple and does not require any sophisticated skills or technology.

Along with the light steel structure system, Hsieh's collaborative construction model has also been exported around the globe.

Projects have been realized in China, Nepal, and the Philippines. Hsieh is now looking at opportunities in Latin America and such African countries as Nigeria, Rwanda and South Africa. European countries with a large influx of Syrian refugees have also shown interest in cooperating with Hsieh to solve their housing shortage problems.

Reward in the Next Life

Hsieh and his team will not stop at building brick-and-mortar houses; they will also build an online platform that focuses on light steel structures. Through the platform it will become possible to order light steel structures from the steel manufacturer and have them sent directly to the end customer. Based on Hsieh’s system, architects, materials suppliers as well as furniture and equipment makers worldwide will be able to collaborate to design and build homes and even develop brands to solve the problems they face at specific locations.

What happens if Hsieh’s idea spreads and home construction becomes a part of the productive process instead of consumption, if the cost of building a house becomes “reasonable”? Will architects still be able to earn high incomes?

A smile works its way across Hsieh’s face as he responds without the slightest hint of irony, “Making money? I certainly won’t make any money in this life, but in my next life I will make it big.” Hsieh, the utopian visionary and activist architect, sees his reward in social change that makes the world a better place in the long run.

Translated from the Chinese article by Susanne Ganz