Taiwan's Education Crisis

Who's Teaching Your Child?

Source:CW

The massive rise of temporary workers in Taiwan's teaching ranks has created an unstable education environment and a decline in quality, with few solutions in sight that might reverse the trend.

Views

Who's Teaching Your Child?

By Rebecca Lin, Jin ChenFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 527 )

This May CommonWealth Magazine published a special edition revealing the dark secret behind the Taiwanese government's persistent revenue shortfalls, exposing how many of the country's biggest companies were paying less in taxes as a percentage of their income than the average salaried worker. The result is that Taiwan's tax-to-GDP ratio is the seventh lowest in the world.

The consequences of a perpetually underfunded government have been widely felt throughout society, with no sector hit harder than education.

To save money, all of Taiwan's elementary and junior high schools have resorted to hiring cheaper contract workers, and now one of every six of their teachers are not permanent full-time employees, according to a report issued late last year by the Control Yuan, the government branch in Taiwan responsible for uncovering and censuring improper behavior by public servants or agencies.

Of the nearly 30,000 contract workers in the education system, the majority are "teachers paid by the hour" who earn below NT$22,000 a month (the wage the government subsidizes companies to hire new graduates). They often lack professional teaching certification and sport a high turnover rate.

When Control Yuan member Kao Fehng-shian was investigating two alleged cases of sexual harassment at Taiwanese schools, she was shocked to discover how serious the problem with temporary and contract teachers was.

"Temps and contract teachers were implicated in all of these cases," says Kao, exasperated by the fact that even if the Control Yuan censures the behavior, the situation will continue to deteriorate.

Taiwan has 2.22 million elementary and junior high students. They are the future, but who is actually teaching them?

Too Many Temps

Lu Yung-sheng, the principal of Tai-He Elementary School in Jiayi County, clutched a piece of paper with both hands, glancing at it repeatedly in disbelief.

"I'm actually No. 1 in the country," said Lu, his eyes wide open behind his glasses.

But his school's top ranking was a source of consternation rather than pride.

The document in Lu's hands showed that in the most recent school year, 42 elementary and junior high schools around the country had more than 45 percent of their classes taught by non-professional teachers.

At Taihe Elementary, located in Alishan in a tea-producing area, the ratio was the highest in the country at 70 percent. Two out of every three classes were taught by contract teachers hired on one-year contracts or paid by the hour.

Parent Association head Chien Wen-chang, a tea producer by trade, is clearly worried about what the staffing problem means for the future.

"I don't know what kinds of teachers are teaching the children. All I know is that they're always changing. Everybody is worried, and we don't know if our young ones are actually learning," he says as he anxiously rubs together palms as coarse as sandpaper from his years of handling tea leaves.

When a new school year begins in September, Tai-He Elementary School will see another staff overhaul, with only four full-time teachers left and the rest temporary workers.

Taiwan's Teacher Shortage

In fact, the remote Tai-He Elementary School is not unique. The teacher shortage has spread to all corners of Taiwan.

When principals of elementary and junior high schools get together these days, the conversation may first turn to a controversial 12-year national education program soon to be implemented, but it invariably ends up focusing on where to find teachers and how to retain them.

Unable to find qualified applicants, schools are left scrambling to make up the shortfall with temp teachers who have not received formal training or professional certification.

When the head of administration at Hsinchu Municipal Guangwu Junior High School, Lin Mao-cheng, tried to hire a science teacher last year, he needed to announce the opening six times and lower the minimum qualification required to a college degree in a related field before he found somebody.

"Teaching quality simply can't be improved," Lin sighs.

What is truly ironic, however, is that while schools struggle to find qualified staff, there are 70,000 "stray" teachers in Taiwan unable to find work.

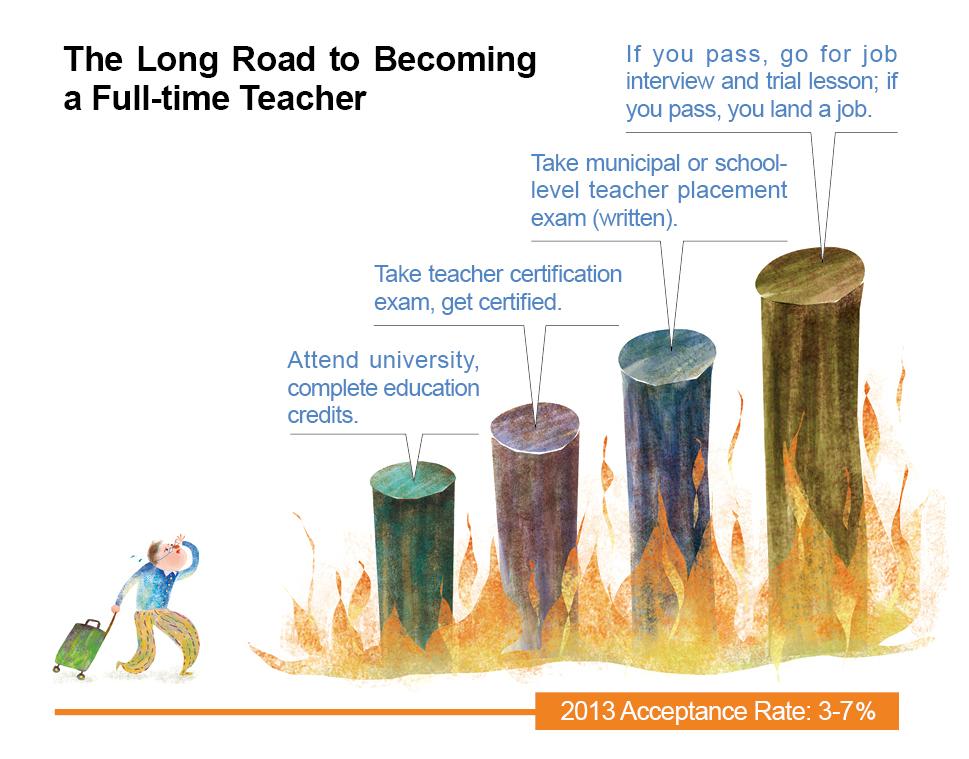

Over the past 10 years, 130,000 people have obtained teaching certificates, but only 57,000 have found teaching positions in schools, according to Ministry of Education figures. The remaining 73,000 remain outside the system, unable to squeeze through the door.

So what's the problem? In a word, money.

"Teachers paid by the hour at the junior-high level make NT$360 per class. How can people live on that?" asks Lin.

Two types of unofficially hired teachers exist in Taiwan. One, the "contract teacher," gets a one-year contract, is paid about the same as full-time teachers, and has roughly the same workload. The other, the hourly paid temp teacher, works when there are classes to be taught and gets paid by the hour.

If hourly-paid temp teachers are scheduled for the maximum 18 classes a week at a junior high school, they stand to earn NT$25,000 per month. At elementary schools, where the hourly wage is NT$260, monthly pay is only NT$20,800, below the NT$22,000 level seen as a minimum for salaried workers.

These exploitative wages have scared many prospective teachers away.

Tax Policy Distorts Education System

An alarming increase in teachers paid on an hourly basis has been seen at schools across Taiwan in recent years, but "the situation has become really serious in the past year," says Hsueh Chuen-guang, the president of the Secondary and Elementary Schools Principals Association of R.O.C., shaking his head.

He says the turning point was the new income tax system for teachers imposed in 2012.

Teachers in Taiwan were required to pay income tax for the first time ever last year, a policy not popular with the rank-and-file. To ease teachers' resistance to the new approach, the government implemented a "pay taxes, teach fewer classes" policy that reduced the class loads of elementary and junior high teachers (usually by two to four fewer classes per week) for the same pay in exchange for paying taxes.

With 160,000 full-time elementary and junior high school teachers in Taiwan, the policy left at least 460,000 classes per week without a teacher, the principals' association estimated. To fill the gap, at least 20,000 more teachers were needed, but the Education Ministry was only willing to offer subsidies based on the hourly rate to fund temp teachers rather than providing more manpower.

In other words, of the NT$7.2 billion in tax revenues gained by taxing teachers' income, about 76 percent has gone into hiring "hourly teachers" to fill the shortage created by the policy.

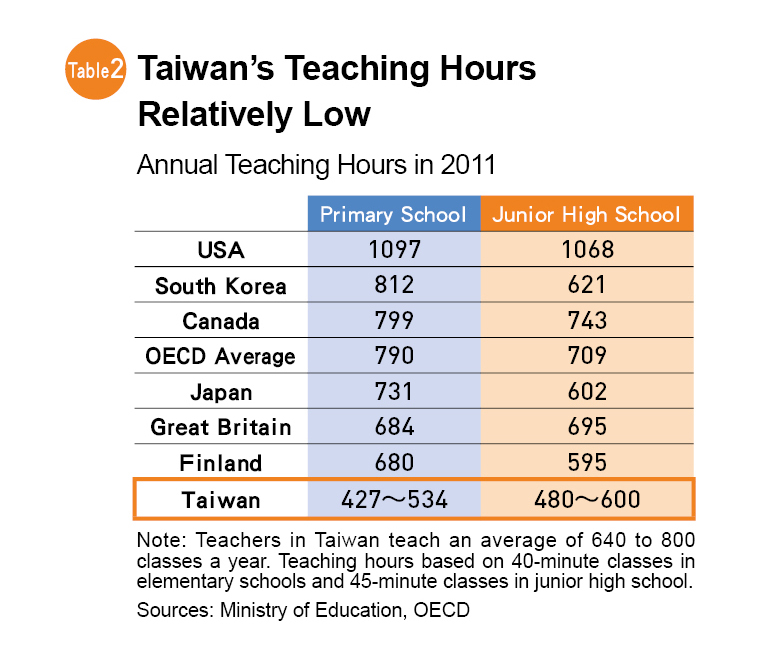

Yet the amount of time spent by Taiwan's teachers in the classroom before they lost their income tax exemption was already low by world standards. The average 600 hours per year taught by junior high teachers and 530 hours taught by elementary school teachers were not only 10-20 percent below the average in OECD countries, but also lower than in neighboring Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong and China. (Table 1)

In addition, facing an aging population and the prospect of fewer students in the future, schools over the past 10 years have been reluctant to hire new permanent full-time teachers, opting instead for a contract worker when an opening arises.

According to Education Ministry regulations, contract and temp teachers are not supposed to exceed 5 percent of all teachers in Taiwan, but the reality is that in 2012 that figure exceeded 10 percent, and 20 percent in certain cities and counties.

This indicates that the wave of "contract workers" on campuses around the country is growing bigger, with one of every six teachers a "temporary worker."

"The foundation of K-12 education system is crumbling," laments professor Chuang Chi-ming, the former president of National Taipei University of Education, which is dedicated to cultivating the country's teachers. The high turnover rate of local teachers is a natural consequence, he says, of the low wages in Taiwan's education market and the limited future a career in education presents.

Contrasting Taiwan's plight with Finland's model education system, Chuang says Finland's high quality of education is founded on the high demands made of teachers during the training process. They must show good character, high aptitude and an ability to teach to make the cut, but they are also guaranteed lifetime job security. Taiwan, on the other hand, is willing to use teachers paid by the hour.

"We can't ask for much when it comes to teacher qualifications, much less the teaching process," Chua ng says.

Because the school system cannot attract qualified teachers, it has become flooded with temporary workers who have not received professional training.

Even in New Taipei, for example, which is willing to invest in education and requires every school to have at least 1.7 teachers per class (approximately 30 pupils in grade school and 40 pupils in junior high), not all of those teachers are qualified.

68% of 'Hourly Teachers' Lack Credentials

"Among contract teachers, about 10 percent do not have teaching certificates or teach courses outside their areas of specialization," admits Kung Ya-wen, the deputy commissioner of New Taipei's Education Department, partly because the municipality covers such a vast area with localities where teachers are hard to find. And that's for contract workers who receive salaries and benefits commensurate with their full-time peers. It's even harder for New Taipei to find people with professional teaching qualifications to work for an hourly wage.

In Kaohsiung in southern Taiwan, 68 percent of the teachers it pays by the hour lack professional certification.

Though the local governments responsible for carrying out the country's education policy are fully aware of the problem, they feel helpless to do anything about it.

The head of Kaohsiung's Education Bureau, Sin-huei Jheng, grabbed a calculator and punched in some numbers to show a CommonWealth reporter how little leeway the city has. Out of Kaohsiung's total education budget of NT$45.3 billion, Jheng said, nearly 96 percent goes to fixed expenses, including teacher and staff salaries, leaving only NT$1.8 billion in discretionary funds.

Changing "hourly teachers" to full-time professionals would cost two to two and a half times as much, he contends.

"The central government is only giving me NT$700 million. The city has to come up with another NT$800 million in subsidies on its own, and we also have to finance pensions and other things," says a frustrated Jheng.

"Local governments have no way of shouldering such high personnel costs."

The Education Bureau mobilized principals last year to appeal to teachers' emotions and plead with them to teach another two to four classes a week to ease the city's financial burden, but only about a third of them were willing.

"When full-time teachers teach another class, they only get another NT$260, and that's subject to tax," says the president of the Hsinchu City Teachers Association, Lai Hsiao-ning, echoing the view held by a majority of teachers around the country.

Revolving Door Crisis

The teacher shortage and use of unqualified instructors has only exacerbated what has long been the major headache of many Taiwanese parents: the uneven caliber of the country's teachers.

A Mrs. Wang, who lives in a "star" school district in Taipei, said that when her daughter was in the third grade, she had a contract teacher who worked very hard and was able to design activities targeted at the needs of each student.

But that teacher only stayed at the school for a semester before leaving to get ready for exams to earn permanent teacher status. Mrs. Wang's daughter got another contract teacher in the second semester, but this one had no experience and certain emotional problems, making the lives of the parents and the children difficult.

When the daughter reached the fourth grade, the class's full-time homeroom teacher, who had already taken vacation for two semesters, asked for another year off, requiring the hiring of another contract teacher. But that sparked a backlash among the parents, and the school's principal had to get involved to persuade the teacher to take only a semester off rather than a full year.

From a star school district in the nation's capital to a remote elementary school in Alishan, students around Taiwan have all felt the scourge of education crises resulting from this constantly revolving door.

One of these crises is fragmented learning.

"When we change teachers every year, how can we improve the curriculum?" asks Liu Wei-chi, the principal of Zhonghe Elementary School in Alishan. Liu believes that a school's curriculum must be carefully coordinated and continually broadened and deepened, but because teachers are constantly rotating in and out, when a new teacher arrives, the school must start back from scratch. The result is that students learn little more than fragments of a subject rather than gaining knowledge in a systematic way.

Everybody Saving Money

Why has it come to this? For a very simple reason: The government is short of money.

When Huang Tzu-teng, the deputy director general of the Education Ministry's K-12 Education Administration, was questioned by the Control Yuan in its investigation into the education system, he admitted, "If officially hired teachers were used to make up the dropped classes, there would have to be increased funding."

Huang explained to CommonWealth Magazine that only two options exist to solve the problem: one is to find the money to enable local governments to hire permanent full-time teachers; the other is to change the "pay taxes, teach fewer classes" policy. But "right now, both of those roads are blocked," he says.

The central and local governments have blamed each other for the problem, creating a chasm between the two. The Ministry of Education, which is responsible for setting policy, stands so far removed from the front lines of the system that it has failed to develop a feel for how serious the problem is and the harm it is doing to children.

Because of its isolated position, the ministry has resorted to simply managing numbers, issuing official documents at a furious clip, demanding that cities and counties increase their teacher-to-class ratio from 1.5 today to 1.7 in four years and limit the number of contract teachers they use to 5 percent of their total teaching staff. The ministry has also created a special task force to study the problem, but promised an actual proposed solution no earlier than next year.

Taiwan's Crumbling Education System

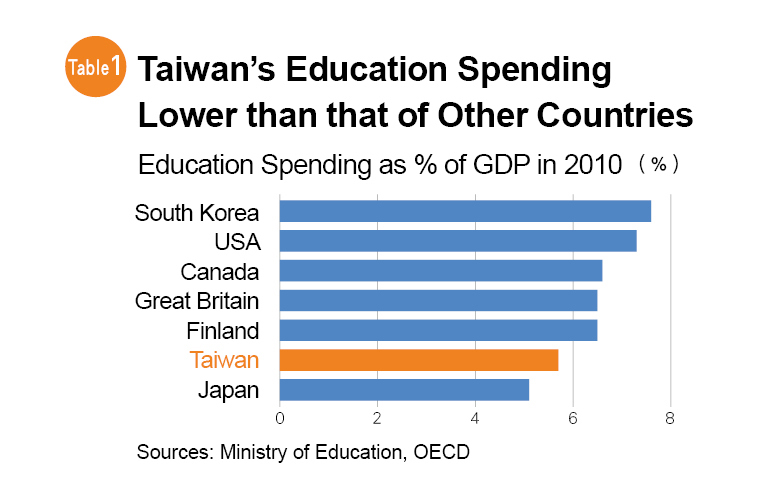

In fact, Taiwan's education expenditures as a percentage of GDP have always been below the international average. The ratio rose from 5.74 percent in 2010 to 6.07 percent in 2011, but that was still below the OECD average of 6.3 percent. (Table 2)

In addition, the Education Ministry has continued to shrink the amount of its funding allocated to K-12 education, going from 40 percent of the total education budget last year to 39 percent this year, representing about a NT$1.1 billion decrease.

About NT$20 billion has been budgeted to subsidize high school and vocational school fees as part of the new 12-year education program (which hopes to extend free public education to 12 years from the current nine years), and also improve the quality of the country's high schools.

Education is the last line of defense for social equity and justice, especially public schools. But this last line of defense is on the verge of collapse.

"No matter how poor you are, you can't impoverish children's education," has been the consensus in Chinese society since ancient times. But not only is government funding insufficient at present, the resources available have been poorly allocated.

"K-12 education is most worth investing in, but Taiwan has followed the opposite direction," says former National Taipei University of Education president Chuang.

The entire country, from the Ministry of Education to teachers and parents, has been so focused on the debate over extending Taiwan's nine-year education system to 12 years that it has ignored the rapid deterioration of Taiwan's once solid national education foundation.

In such an environment, everybody is a loser, but those making the biggest sacrifice are members of the next generation.

Translated from the Chinese by Luke Sabatier