Taiwan Digital Minister Audrey Tang: Citizen Hackers Save the World

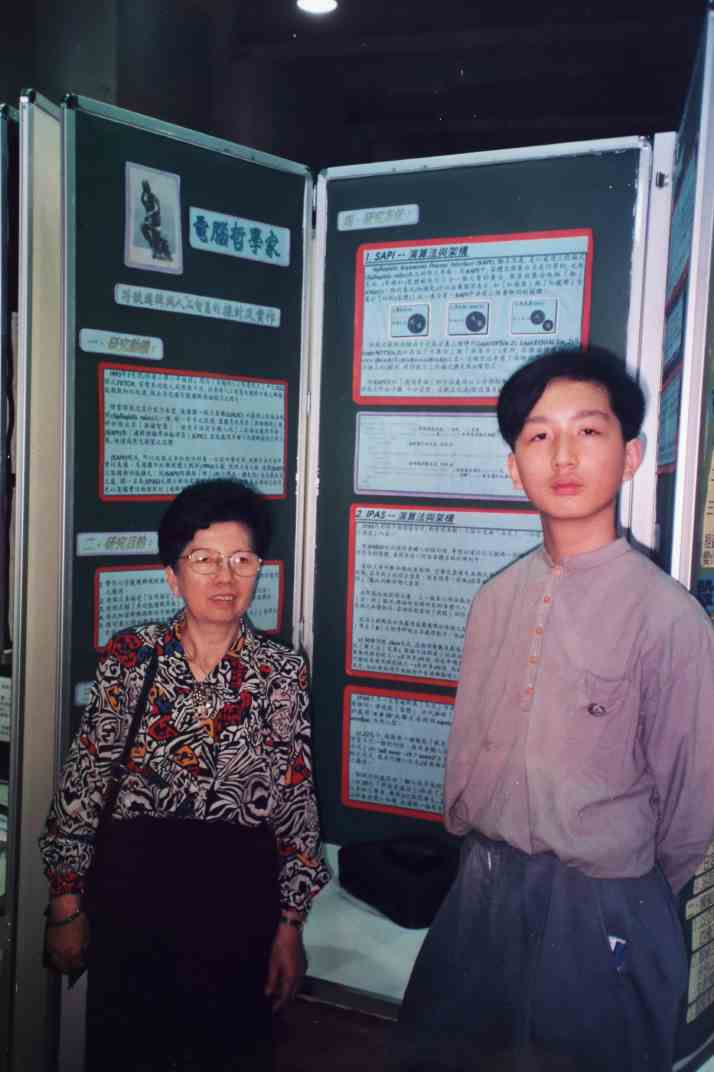

Source:Ming-Tang Huang

Taiwan‘s Digital Minister Audrey Tang is internationally known as a genius “made in Taiwan”. A child prodigy, although Tang early on discovered the Internet as an autodidactic learning tool, her formal school career was anything but smooth sailing. How did she go through school boycotting and rebellion before things took a turn for the better.

Views

Taiwan Digital Minister Audrey Tang: Citizen Hackers Save the World

By Cathy Chiangweb only

During the coronavirus pandemic, Audrey Tang, whose formal title is minister without portfolio, again made headlines abroad with her creative use of digital technology in fighting the outbreak in Taiwan. Yet although much has been written about her, Tang remains an enigmatic personality.

Many child prodigies prefer to bury themselves in the cloistered realm of laboratories. As scientists and professors, they seek to create new breakthroughs in human knowledge. Yet Tang, who was already a famous computer wiz in childhood, chose to step out into the world as an adult, taking an active role as a changemaker.

First, she helped Taiwan’s democracy movement finalize many “open government” projects, which subsequently earned her an invitation to join the government. A vocal advocate of direct democracy, she aspires to serve as a communication channel between the government and the people. In her latest mission, during the COVID-19 pandemic, she facilitated the speedy setup of a facemask distribution system via Taiwan’s national health insurance and other digital pandemic-prevention measures, which earned her even greater popularity.

Many people who have worked with Tang admire her for her astounding efficiency, encyclopedic knowledge and humble attitude.

They are also curious to know why Tang is so determined to make the protection of Taiwanese democracy her lifelong calling.

Her self-description “A civic hacker who grew up among Tiananmen exiles” might offer a glimpse at the answer.

Encounters with Chinese student protesters in the wake of the Tiananmen protests of 1989 were a turning point in Tang’s life. At the time, she was 11 and living in Germany, where her father pursued a doctorate at the Saarland University. Tang’s mother Lee Ya-ching and her brother Tang Tsung-hao had also moved there for a year.

Tang’s father is a veteran journalist who formerly worked as deputy editor-in-chief at the China Times, then a major newspaper in Taiwan. His doctoral thesis was about social action and networks during the Tiananmen protests.

Before the June 4 crackdown, he had spent more than 20 days at Tiananmen Square, getting to know many leaders of the democracy movement.

Therefore, Chinese dissidents who subsequently went into exile in Germany often gathered at her home in Germany. Their discussions about the future of China left a deep impression on young Audrey.

As Tang was mentally much more mature than her peers, she was frequently bullied by her classmates in school in Taiwan. The situation was so bad that she temporarily refused to go to school and even contemplated suicide.

Her father believes that the one year that physically and mentally scarred Tang spent at the Albert Schweitzer elementary school in Saarbruecken constituted a “healing” process.

In Taiwan, Audrey had skipped a grade. Normally she would have entered junior high school, but since she did not speak German at the time she was placed in fourth grade.

It was the first time in Audrey’s life, that she, a gifted student, had gone to school with mates who were younger than she was. She was surprised to find that the German students were far more mature than their Taiwanese peers, and that they respected each other.

In an interview with a German journalist, Tang once attributed this to the fact that in Germany adults and children treat each other as equals. “If you treat kids like adults, they will behave like adults,” she said.

In Germany, students are taught in line with their aptitude and are allowed to make mistakes. Back then, students in elementary school and the lower grades of secondary education were attending classes only half days, which left them with ample free time to explore their own interests. This and other special features of the German education system, such as attaching importance to the rights of disadvantaged students, greatly influenced Tang and her parents when they subsequently became involved in alternative, experimental education in Taiwan.

When children have enough downtime, they will come up with ideas and games. Play and creativity are closely aligned, and as Tang Kuang-hua puts it, when parents initiate dialogue with their children, “the kids will ask questions and won’t be afraid of difficult problems.”

Argumentative Dialogue About the Need to Attend School

For Tang Kuang-hua, who believes in Socratic education principles – stimulating critical thinking and generating ideas by asking and answering questions – the German education ideals seemed a quite good fit.

“You need to be humble when dealing with children,” he points out. Parents must allow their children to challenge them, adopting a mindset that is best described by Socrates’ famous statement “I know that I know nothing.” Parents can help their children clarify their thoughts and ideas by continuously asking and answering penetrating questions in a mutual dialogue.

While living in Germany, the Tang family was, for instance, once engaged in a massive debate about the necessity of attending school.

Audrey and her brother Tsung-hao listed a few major reasons why they felt it was not necessary to go to school. These included boring curricula and the fact that the siblings’ German was already good enough to master daily life. They even put together a self-learning timetable and learning objectives.

Seeking support, Tang Kuang-hua and Lee Ya-ching spoke with university professors, teachers and education experts. In the end, the children accepted that they had to go to school because school education is compulsory in Germany.

Another time, Tang Kuang-hua caught his kids playing a computer game. He ordered them to stop, which provoked their vocal protest. Audrey and her brother argued that their father had no reason to oppose the game given that he had no clue what it was about. After finding out that the game, called Civilization, was quite educational, he no longer opposed it.

Tang Kuang-hua also often seized the opportunity when current affairs were making the headlines to teach his children.

In 1992, when the Tang family lived in Germany, public service employees staged a massive strike that disrupted bus and rail traffic, mail delivery and garbage collection. Making a mental calculation, Audrey Tang concluded that the expenditure of the German government would balloon if the labor union demands for higher wages for every employee were accepted, eventually leading to higher taxes. She wondered if that would make the economic situation worse.

But in the end, the labor unions and the government negotiated an agreement under which staggered wage hikes were agreed upon, depending on a worker’s income.

“That’s how justice should work,” Tang Kuang-hua told his daughter.

When Audrey Tang was fourteen, she began to homeschool, and her mother quit her job in support. But as the homeschooling movement was still in its fledgling stages in Taiwan, the Tangs were staggering along, finding their way as they went. The big turnaround came when they met several people who were active in education reform.

Among them was Yang Wen-guei, founder of the Nurturing Giftedness International Foundation, who was serving as a lecturer at the Taipei Municipal Teachers College (now University of Taipei) at the time. He first met Audrey Tang when she was only nine and immediately knew that she was different from the average kid. Since the continued bullying in school had traumatized her, she was exceptionally mature for her age, which became evident in the questions she would bring up: Why do I need to go to school? What is the point of quarreling? Why do people die?

Yang introduced the family to learning resources and reminded Lee Ya-ching to take care of her daughter’s emotional needs as much as of her learning.

Peter Yang Mau-hsiu, founder of the Caterpillar Philosophy for Children Foundation, guided Audrey Tang and her peers in a reading group, helping her develop an open-minded attitude by engaging in discussions and listening attentively to what others had to say.

The late Chu Tien-chen, a mathematics professor at National Taiwan University, played the role of mentor. He introduced Tang to higher and further mathematics but also made her delve into history, geography, human life and even the soul.

From being educated to reforming education

“How can you muster moral courage if you only care about grades?”

In the 1990s, Tang Kuang-hua and Lee Ya-ching became personally involved in education reform due to their children’s negative experience with the established school system and their need for alternative approaches, with the whole family even participating in street protests.

The reform advocates were unhappy about the school system’s one-sided focus on grades and advancement into highly competitive “good” higher-level schools. Taiwanese teenagers attend school all day, and the vast majority then shoulder their school bags and drag themselves to cram schools.

Tang Kuang-hua strongly felt that young people deserved a different life.

“If children can only compete on grades, if there is no other choice, then how can they muster the moral courage when facing an authoritarian government as adults?” asks Tang Kuang-hua.

Many people praise Tang Kuang-hua for raising a genius, but he believes that inborn giftedness is of secondary importance. As a father, he is proud of his daughter’s good-natured, empathic personality.

He vividly remembers an episode during a hike when eight-year-old Audrey saw how another child deliberately destroyed a spider net that carried a spider. Audrey broke into tears and cried loudly, making attempts to attack the perpetrator. Watching from the sidelines, Tang Kuang-hua realized that Audrey was very sensitive to the pain of other living creatures.

Many years later, he asked her why she was so keen to protect the little critter.

She responded that she felt pain when witnessing injustice. “When the spider was attacked, it felt like I was being assaulted; that’s why I wanted to protect it,” she explained to her father.

As Tang Kuang-hua sees it, a caring personality and an altruistic spirit are more important values in life than talent, income and social status.

That’s probably why Audrey Tang later on became actively involved in building open source communities such as Taiwan’s civic hacker community g0v, aspiring to make governments more transparent and accountable through digital tools.

Have you read?

♦ Local Leaders Approval Survey Hints at Taiwan’s Future

♦ Why Taiwan's superb handling of COVID-19 could be a risk long-term

♦ Chen Chien-jen: Solidarity the Key to Taiwan’s Successful Pandemic Fight

Translated by Susanne Ganz

Edited by TC Lin

Uploaded by Penny Chiang