Dying alone in Taiwan: Can anybody help?

Source:CommonWealth Magazine

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the extent to which people in Taiwan live and die alone. People of all ages are leaving the world without anybody by their side, and with millions at risk of suffering the same fate, can anything be done to reverse the trend?

Views

Dying alone in Taiwan: Can anybody help?

By Rebecca LinFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 730 )

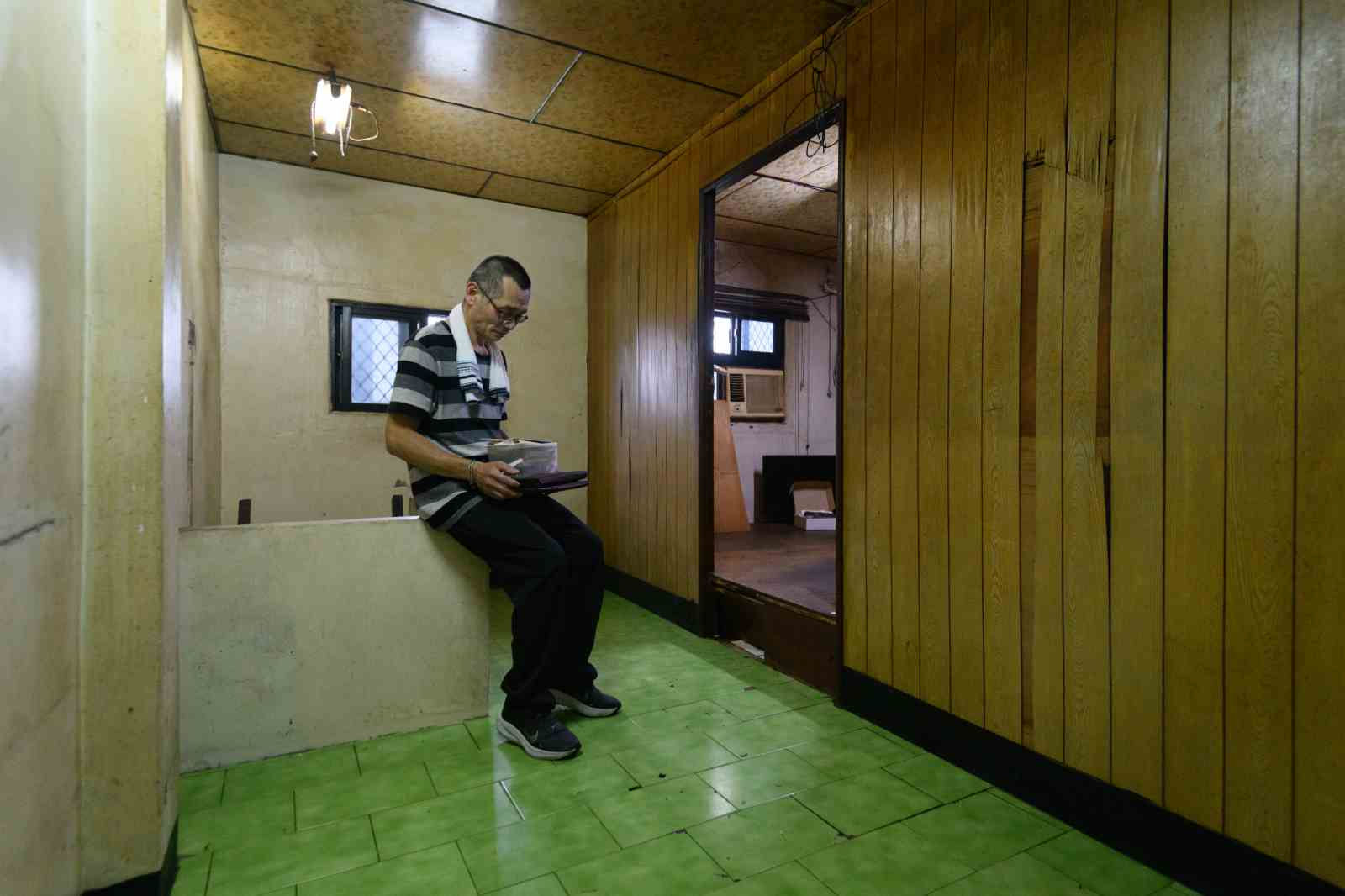

When 43-year-old Mr. Liu was found by the building’s superintendent, he had been lying on the floor of his apartment for three weeks. He owned a small factory, and his home in New Taipei, a relatively upscale residence, was only a 7-minute walk from the nearest subway station.

A closed-circuit camera filmed him entering the elevator of his building three weeks earlier, and he was never seen leaving again. His neighbors barely had any impression of him.

Cases such as Mr. Liu’s of people dying alone are increasingly common in Taiwan, a phenomenon made even more noticeable by the recent COVID-19 outbreak, when several people with the disease were found dead in their residences. Fang Ho-sheng (方荷生), the head of Zhongqin Ward in Taipei’s Wanhua District who has lived in the area for more than 60 years, couldn’t help but repeat how “uncomfortable” the trend has made him feel.

“Over the past 20-plus years, I’ve handled hundreds of similar cases. In the past, most of them were old veterans who came to Taiwan after the [Civil War in China],” Fang said.

“But now, I take care of more than 200 seniors, and over half of them live alone or are unable to be taken care of by their children and are simply left to live in the community. People are increasingly dying alone, and I have no idea how to help.”

Funerals handled by local authorities rather than relatives

Just as death has never been limited to a specific age, dying alone is not a nightmare reserved exclusively for the elderly. As more people face “solitary deaths,” local governments are being forced to adapt.

New Taipei is one of several cities that organize mass public funeral services, but because of the growing number of people who refuse or cannot afford to make funeral arrangements for deceased relatives, New Taipei has been forced to increase the frequency of these funeral services to twice a week, up from once every two weeks previously.

For the dead who do not have any relatives show up, they are cremated 25 days after the public notice of their deaths was issued. Their ashes are then included in a joint farewell ceremony held once every three months before being placed in a public columbarium.

With the population of people living alone on the rise, New Taipei launched a plan last year that “if you apply, you can be part of a public funeral or green burial if no relative handles your remains within seven days of the public posting of your death,” said Huang Fang-tse (黃芳子), the head of the Banqiao Funeral Home in New Taipei.

(Source: CommonWealth Magazine)

(Source: CommonWealth Magazine)

Nearly 6 million people at risk

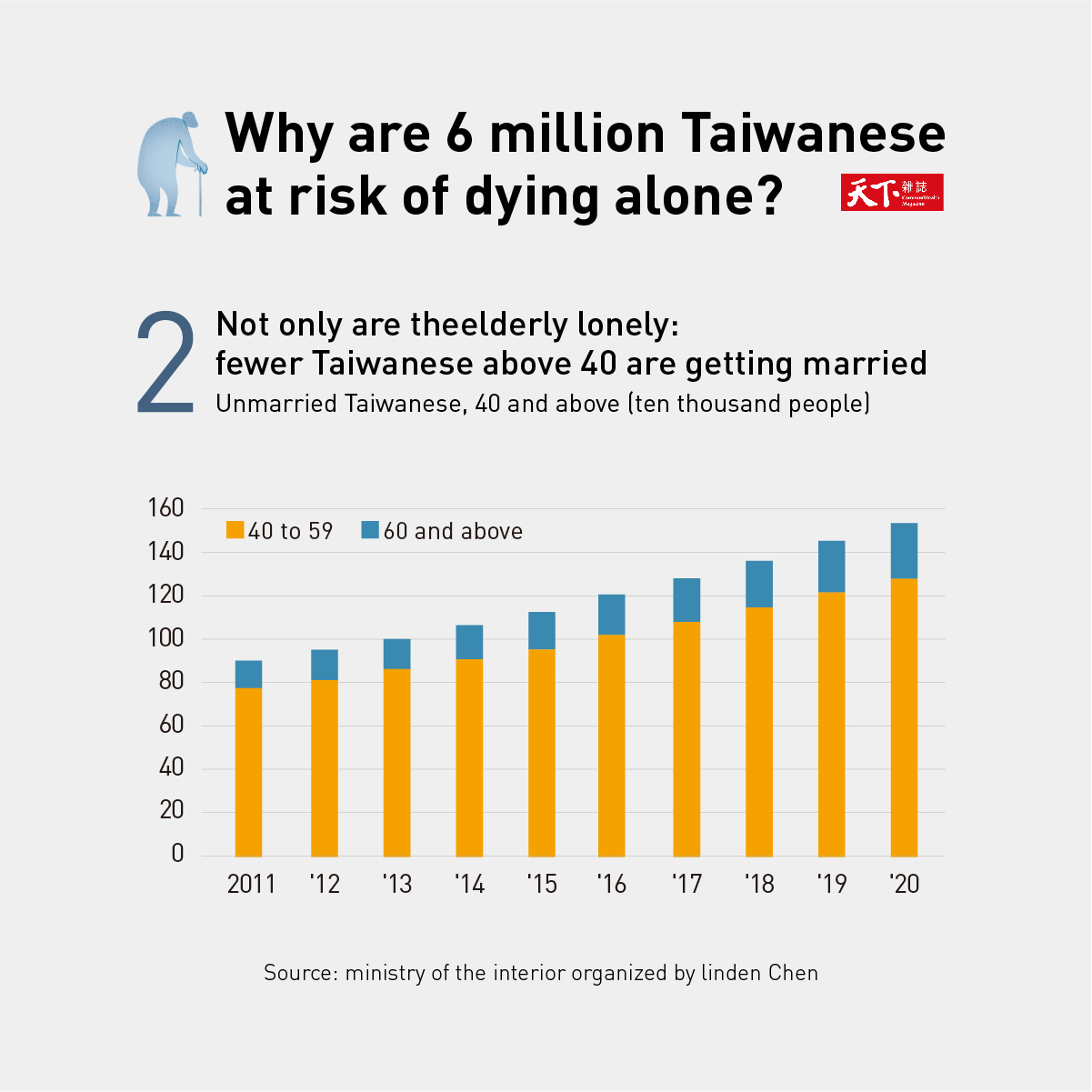

Lin Mei-chun (林玫君), a professor with the General Education Center at National Kaohsiung University of Hospitality and Tourism, attributes the rising number of people dying alone in large part to dramatic changes in social structures. Among them, she said, are increases in the number of people who live alone or never get married, shortfalls in financial resources, a rise in middle-age divorces, unhealthy extensions of life, and more cases of the elderly taking care of the elderly.

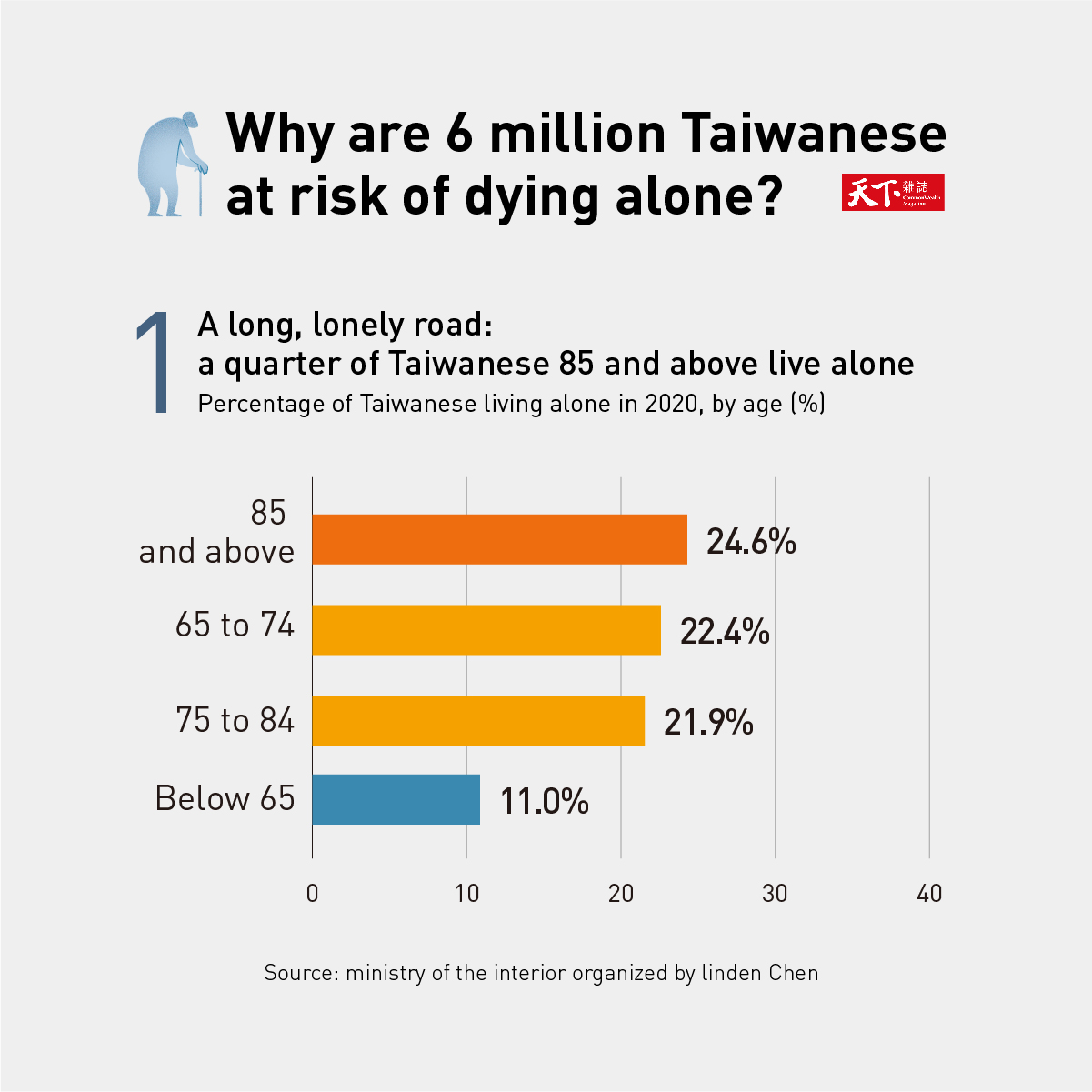

In Taiwan last year, there were 3.01 million single-person households, exceeding the 2.54 million households with nuclear families, according to Ministry of the Interior statistics.

If one adds the 860,000 single-parent households (about 2.17 million people) and the 160,000 grandparent-headed households (about 550,000 people), there are in total nearly 6 million people in high-risk families in Taiwan.

In 2020, there were 1.04 million households in the highest-risk categories – senior citizens living alone or elderly people taking care of themselves.

(Source: CommonWealth Magazine)

(Source: CommonWealth Magazine)

The police are usually the first to witness these “solitary deaths,” which have become “commonplace in recent years,” said Wu Chia-sen (吳家森), the head of the Guangming Police Station in New Taipei’s Sanchong Precinct.

Wu said that if no direct blood relatives can be found, the police will access the household registration system to see if the deceased had any siblings or children.

Mr. Liu, who never married, was one of Taiwan’s 3.01 million single person households. His parents were divorced when he was young, and he began living alone after his mother died.

(Source: CommonWealth Magazine)

(Source: CommonWealth Magazine)

When the police found his body but no apparent relatives, they found out through the household registration system that his father still had siblings in their native Yilan County, but the family did their best to avoid getting involved. Eventually, the police made contact with an older cousin of Mr. Liu and persuaded her to claim his body, but she confessed to not having even the slightest memory of her late relative.

Taiwan Care Management Association director Chang Su-hui (張淑慧) began paying attention to the issue of “solitary deaths” last year, with a particular interest in middle-aged Taiwanese who die alone.

She observed that the problems in this demographic usually involve internal family conflicts or professional failures and the subsequent inability to deal with setbacks, resulting in depression and mental disorders that gradually pull them away from society. Though the setbacks caused by failures can be debilitating, growing estranged from others is what does them in, Chang said.

(Source: CommonWealth Magazine)

(Source: CommonWealth Magazine)

Combating the fear of dying alone

Regardless of one’s social and economic status, the growing phenomenon of dying alone is striking fear in people’s hearts.

Keelung City Councilor Wang Hsing-chih (王醒之) said he knows a retired university professor who lives alone, her husband having passed away and her children living abroad. She was diagnosed with cancer, and though her treatments leave her physically weak, she still forces herself to take part in daily community activities with just one goal: getting a small cake handed out at the event to take home and share with her doormen.

“I asked her why she does this. She said that she lives alone and she doesn’t want to die at home without anybody knowing,” Wang said with a sigh, knowing that many people share her plight. “She knows she has to find more ways to connect with society for her own sake, and is doing her best.”

Amid this mounting angst over the prospect of dying alone, is there anything the country or society can do?

“What is the concept behind social welfare? It is ‘what you lack I will provide.’ But nobody is paying attention to the need for ‘companionship,’” Wang said.

Though Taiwan has community care centers and a ward chief reporting system under its long-term care framework, the city councilor argued that they generally cater to seniors with special situations, a concept he believed is outdated. He suggested that community services in the future be more organized and more conscious of building interpersonal connections.

“They don’t necessarily have to take care of each other, but at least give people more of a sense of social presence,” Wang said.

Wang’s “Anti-fall Work Team” program in Keelung reflects his interest in “symbiotic communities.” It mobilizes younger people to do repairs and renovations in the homes of the elderly, who in turn pass on their skills and expertise to the work teams, promoting self-sustaining interaction and fostering a community environment in which people connect with each other.

(Source: CommonWealth Magazine)

(Source: CommonWealth Magazine)

Reshaping the social welfare system

Government policies to address loneliness should also not be limited to reliance on the social welfare system.

National Cheng Kung University Institute of Gerontology professor Liu Li-fan (劉立凡) bluntly describes Taiwan’s existing social welfare system as an M-shaped construct, focusing mostly on people at the bottom rung of society and meeting their day-to-day needs.

Yet “the most unfortunate are the middle class. Those who die alone are not necessarily people living below the poverty line,” she said, having observed many retired managers, for example, who would rather starve than ask for help “because they were too proud to do so.”

Policies must take self-esteem into account

Liu argued that social policies addressing loneliness should encompass employment, work, education, and residence issues, with a particular emphasis on caring for people’s psychological needs and helping them find resources that maintain their health and lifestyles. Instead of being limited to “giving” material assistance, they must embrace a strategy that balances each person’s independence and self-esteem, she said.

A growing number of people are retiring in their 50s, for example, but cannot find jobs offering them the same status as their previous roles. For teachers or managers, the government or companies could design part-time tasks that enable them to contribute what they have learned while preserving their income and even more importantly keeping them connected to society, she suggested.

“If a person feels that their existence is meaningless, how long can they really live?” Liu said.

Part of the answer is for Taiwan to build up social infrastructure, from creating systems that maintain the safety of those living alone and establishing social networks within communities to strengthening social participation and mobilizing ordinary and professional volunteers.

(Source: CommonWealth Magazine)

(Source: CommonWealth Magazine)

Hondao Senior Citizens Welfare Foundation executive director Lee Juo-chi (李若綺) said society’s greatest need at present is finding opportunities for different generations to interact, especially creating jobs that enable young people to work in their hometowns, to prevent Taiwan from becoming a “no-relationship society” where people are isolated.

Behind every “solitary death” is a tragedy, but the phenomenon is not an inevitable offshoot of an aging society. Instead, it reflects indifference and selfishness. Fostering a society that cares about people and respects life is the best medicine for combating the “no-relationship society.”

When families are no longer fortresses of last resort, when kinships erode, and when work can no longer guarantee people’s livelihoods, how can connections between people be maintained and strengthened? That question is one everyone needs to ponder.

Have you read?

♦ New directions in cross-strait relations: Richard Bush

♦ Covid Graduates: "The pandemic only makes us stronger"

Translated by Luke Sabatier

Uploaded by Jane Chen