How can Taiwan fix its doctor shortage?

Source:Ming-Tang Huang

Taiwanese medical schools can enroll a maximum of 1,300 students per year, a government-set quota that has not changed in 24 years. In Taiwan’s aging society, this is not enough to satisfy rising demand for medical services. What can be done to address the imbalances to future-proof Taiwan’s healthcare system?

Views

How can Taiwan fix its doctor shortage?

By Sydney Peng, Rebecca LinFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 745 )

Taiwanese medical schools can enroll a maximum of 1,300 students per year, a government-set quota that has not changed in 24 years. In Taiwan’s aging society, this is not enough to satisfy rising demand for medical services. What can be done to address the imbalances to future-proof Taiwan’s healthcare system?

Three national universities – National Tsing Hua University, National Chung Hsing University, and National Sun Yat-sen University, have just gained official approval to launch state-funded second entry degrees in medicine, for which a bachelor’s degree in a related science is the prerequisite. Although the programs have not yet been launched, the universities are already posting application information online.

Within the medical community, doubts are being voiced over the wisdom of introducing an alternative route to medical practice.

In a letter to the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health and Welfare, the Taiwan Medical Association has urged the government to respect the existing cap on the total number of physicians.

The main reason for the backlash from the medical community is the quota that the state sets for the number of med students that can be enrolled at Taiwanese universities per year.

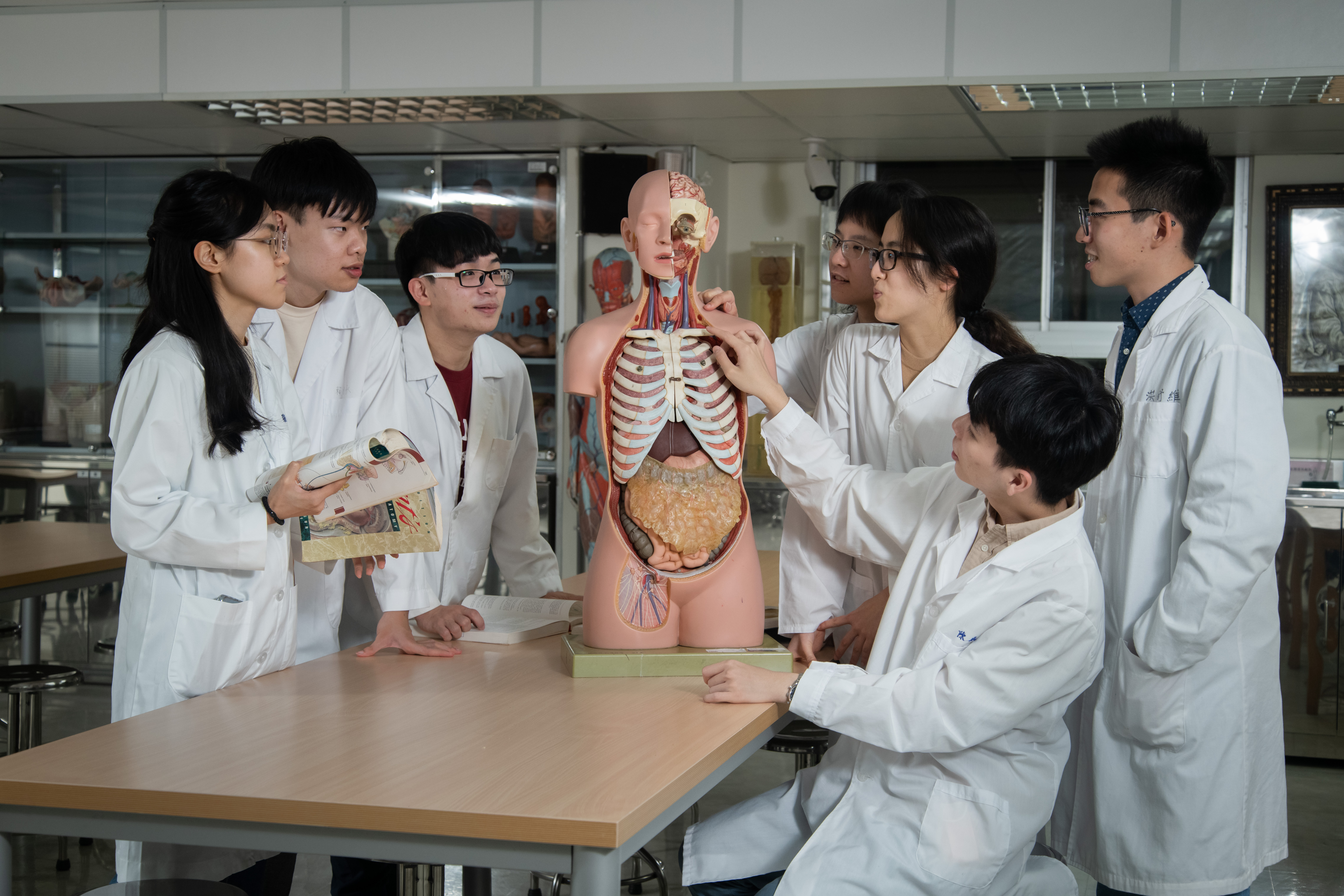

(Source: Ming-Tang Huang)

(Source: Ming-Tang Huang)

The so-called “post-graduate departments of medicine” enroll students who have already obtained a bachelor’s degree in another subject. In contrast to traditional medical degrees, which are obtained after six years of studies, the post-graduate medical degrees take only four years to complete. While the first two years of the six-year degrees are devoted to basic courses, the four-year degree programs directly delve into autonomy and other fields of medicine.

Why are the three national universities, which previously did not have medical departments, so keen on opening 4-year post-graduate medical degree programs?

Currently, 13 universities in Taiwan have medical departments. Together they can enroll a maximum of 1,300 med students per year. This cap has remained unchanged since 1998, although the realities in Taiwanese health care have changed dramatically in the past 24 years.

At the same time, the Ministry of Health and Welfare launched a publicly funded 5-year program in 2016 to train medical specialists to be posted in more remote underserved areas, or hospitals under the ministry. The program, which last year went into its second phase, aims to train 750 specialists in internal medicine, surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, and emergency medicine.

That’s why universities that were looking to establish medical schools are keen on founding post-graduate departments of medicine.

Does Taiwan have enough physicians?

Given that Taiwan is an aging society with rising demand for the treatment of age-related diseases and conditions, and that several new hospitals are under construction across the island, around 3,500 physician positions cannot be filled by 2030, based on current medical school enrollment.

Taiwan has an average 21.7 physicians per 10,000 population, which lags far behind the median of 33.6 physicians for the OECD countries. Within the OECD, only Turkey is behind Taiwan, whereas Taiwan’s Asian neighbors Japan and South Korea boast much higher figures.

Contributing to the problem is the dramatic change in Taiwan’s population structure during the past 24 years. While the older population over 65 accounted for just 10.5 percent of the population in 1999, Taiwan will become a super-aged society with one in five persons over the age of 65 by 2025.

“Old people have a lot of needs, the most obvious being medical care,” says Chang Hong-jen, adjunct professor at the Institute of Public Health of National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University and a former deputy health minister. Demand for geriatric care will markedly increase. At the same time, the post-war baby boomers are reaching retirement age by 2030. Given that about 30 percent of active physicians are older than 60 this will lead to a massive retirement wave. As Chang points out, “physicians require care, too.”

Cities and counties across the island are building large hospitals to meet rising demand for the treatment of geriatric diseases and conditions, particularly cancer and chronic diseases, on top of increasing pandemic-related capacity.

Taoyuan, the only city among Taiwan’s six special municipalities with a growing population, is at the forefront of this capacity expansion. Presently, 12 hospitals are establishing or expanding hospitals. At least three new regional hospitals will be built.

National Tsing Hua University is planning a 910-bed hospital in Taoyuan that is expected to be completed in five years. At least 11 regional hospitals will come online by 2030.

The shortage of physicians is the most urgent problem.

A forecast of Western medicine physician manpower developments by the Institute of Population Health Sciences under the National Health Research Institutes (NHRI) in 2019 evaluated six scenarios. Factored in were future medical care demand, physicians’ work hours, and changes in the supply-demand relationship. A key variable is the change in the number of regional hospitals in the coming decade.

If one regional hospital is added per year during the next ten years, Taiwan will lack 3,500 physicians by 2030. This compares with an annual total of 1,300 med students.

Therefore, Taiwan’s physicians’ shortage will most likely become more severe.

While hospitals of all sizes are expected to see doctor shortages, it will be most felt at large medical centers and regional hospitals, as opposed to small clinics.

Why has the cap on the number of medical students not been changed for 24 years?

In an investigation, Control Yuan members Yeh Ta-hua and Lai Ting-ming found that the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health and Welfare both claim that they cannot find the data on which the calculation of this cap was based. The Control Yuan has therefore criticized the implementation of policy based on a seemingly unfounded recommendation as “too arbitrary”.

Over the past 24 years, other countries have moved forward and increased their places for medical students. In the Netherlands, for instance, the number of medicine graduates has doubled. Even Japan, which used to have strict restrictions on the number of med school students, has added 1,000 places for medical students to alleviate the local shortage of physicians.

Yeh decries that the NHRI’s manpower forecast failed to consider emerging medical needs such as epidemics, psychiatrics diseases, mental health, homecare. And she notes that the data were out of date and do not reflect recent changes.

“If the recruitment and training of physicians is a national focus, then we should have a clear legal basis for it, including a mechanism for establishment and withdrawal [of hospitals]. All this should be public and transparent,” she points out.

Do we need to train more physicians?

The number of physicians is related to national health care expenditure, the growth of which is restricted since the National Health Insurance adopts a single payer system. In Taiwan, NHI expenditure accounts for a rather low share of GDP.

In terms of share of GDP, Taiwan’s health care expenditure is low at 6.1 percent compared to South Korea with 8.2 percent, Japan with 11 percent, and the United States with 16.8 percent.

As Cheng Shou-hsia, dean of the College of Public Health at National Taiwan University, points out, health care expenditure is low at 6 percent of GDP because salaries in Taiwan have hardly increased in recent years. Therefore, there is not much room to raise health insurance premiums [which are salary-based]. This stands in stark contrast to South Korea, which has heavily invested in long-term care insurance and the biotech industry.

In terms of healthcare’s share of the national budget, which stands at 11 percent, Taiwan also comes in behind the OECD average of 15 percent. This shows that the government does not invest enough in healthcare, which constricts the industry’s growth potential.

Given that the pie does not get bigger, increasing the number of physicians is a zero-sum game.

Chen Liang-fu, spokesman for the Taipei Medical Association, points out that based on the workload, Taiwan does for sure not have enough physicians. But he admits that “increasing the number of physicians with the current scope of investment in medical resources is difficult.”

Underinvestment in mental health epitomizes the health system’s ills.

In Taiwan, the rate of people struggling with mental problems ranging from long-term insomnia to being suicidal is steadily rising. Are efforts being made to train more psychiatrists to address the growing number of people in need of help?

Over the past five years, the Ministry of Health and Welfare’s quota for psychiatric specialist training has hovered around 51 and 56 people.

Health insurance is an important pillar of the population’s health and safety. The system’s efficiency, however, is built on the sweat and tears of physicians and patients.

Since the NHI budget, the pie that everyone wants to get a piece of, does not get bigger, the number of physicians cannot be increased. At the same time, demand for medical care is rising and becoming more complex, which means our physicians are exhausted from constant overwork.

The NHRI once conducted a survey among physicians, using a questionnaire that found that one out of four respondents said they were planning to quit or retire within three years. Among those who wanted to quit their current jobs, 23 percent were planning to switch to practicing cosmetic surgery at a clinic, and 33 percent were looking to practice abroad.

Predicting Taiwan’s demand for physicians for the coming decade is a challenging task since any tiny change in one variable – be it the hypotheses, work hour calculations, population structure – profoundly affects the big picture.

And aside from setting the total number of physicians, this still fails to solve the three “imbalances” in the system.

The first is an imbalance among the medical specialties. In a super-aged society like Taiwan’s where chronic diseases are very common, internal medicine specialists are urgently needed. However, for many years only around 80 percent of internist positions could be filled.

Next comes the gap between the cities and underserved rural communities as physician density is markedly higher in the metropolitan areas. Taiwan has 244 local communities, towns, and urban districts that have less than ten physicians per 10,000 inhabitants. This does not even meet the lowest standard of the World Health Organization.

The third is the manpower imbalance between hospitals and clinics. When the large hospitals that are currently being built open, they will attract medical personnel like a magnet. As a result, physicians and patients from small hospitals and local clinics will flock to the large hospitals, further aggravating the lack of medical resources in more remote areas.

Taiwan has just three years left before becoming a super-aged society. Do we want to risk that some patients won’t be able to find a doctor anymore? Are we aware that it could be us? We all need to face this harsh reality.

Have you read?

♦ Why are Chinese companies in Taiwan being raided?

♦ Taiwan’s talent drought may raise salaries

♦ New challenges for Taiwan in the 2022 post-pandemic economy

Translated by

Susanne Ganz

Uploaded by Ian Huang