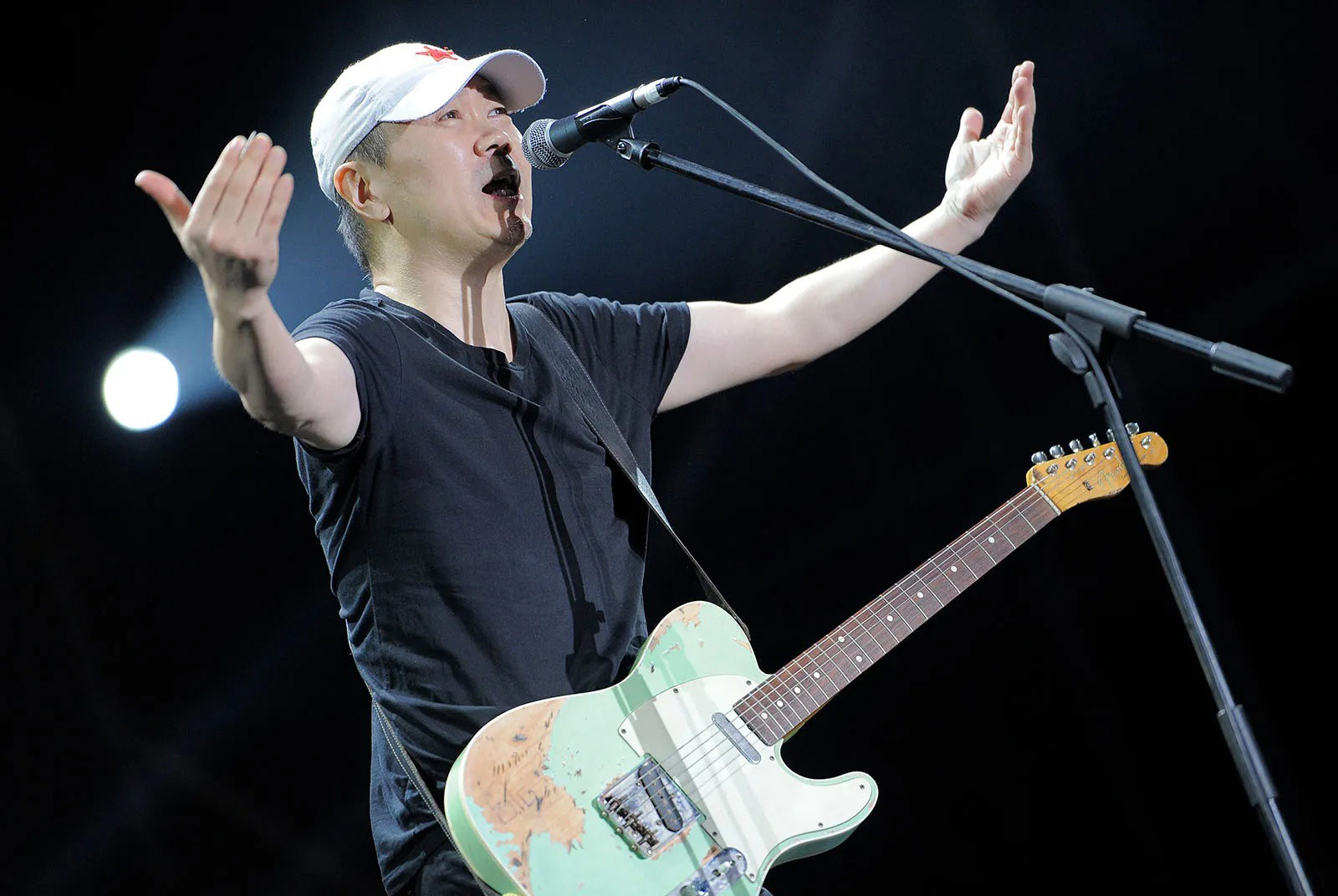

Cui Jian: China’s rock ‘n’ roll legend still on his game

Source:Getty Images

Cui Jian’s latest album “A Flying Dog” won a 2022 Golden Melody Award, an indication that China’s aging rock ‘n’ roll pioneer still has it. In an exclusive interview with CommonWealth Magazine from Beijing, he shares what has kept him going so long.

Views

Cui Jian: China’s rock ‘n’ roll legend still on his game

By Jing Wen Zhengweb only

Attracting 90 million eyeballs is no mean feat, but the godfather of Chinese rock ‘n’ roll Cui Jian (崔健) did it with an online “Keep Going Wild” (繼續撒點野) concert in April that drew 45 million views and 100 million likes.

Despite the unprecedented feat, the 60-year-old no-nonsense Beijinger seemed unimpressed when he spoke with CommonWealth Magazine in an exclusive interview via videoconference from Beijing in June.

“I think that a lot of people pay much more attention to numbers than to my music,” he said.

Cui was shaped by his artistic family of Korean descent. His father was a trumpet player with the Beijing Air Force’s band, while his mother was a member of the China National Ethnic Song & Dance Ensemble. Cui started to play the trumpet himself at the age of 14, a skill that got him into the Beijing Symphony Orchestra at the age of 20.

But it was another instrument that would set him on his lifelong creative path. Not long before joining the Beijing Symphony Orchestra, he bought a guitar for 20 renminbi and ended up playing it better than his instructor, a Mongolian worker, within two weeks. From there, he used his inseparable companion to create a sound that would literally shake China.

It was 36 years ago that Cui performed his signature hit “Nothing to My Name,” a beguiling combination of rock ‘n’ roll and the sound of the “suona,” a Chinese double-reed woodwind instrument. The song was the unofficial anthem of student protesters in China in 1989 and eventually became entrenched as the collective memory of a generation of young Chinese.

Cui’s music has remained popular for so long because of his knack for staying ahead of the times. His 1984 hit “It’s Not That I Don’t Understand,” which was re-released in 1989 on his most successful album “Rock ‘n’ Roll on the New Long March”, featured traditional Chinese hip-hop-like vocals dependent more on rhythm and words than melodies, and his 1991 album “Solution” and 2005 album “Show You Color” contained rap elements.

Aiming for perfection

Though Cui is getting on in years, his music has kept its edge through his dedication to constantly honing his craft.

“There’s always energy in his songs. I’m 60 years old. I’ve accepted my fate, but he hasn’t said one netizen.

A highly creative musician, Cui has released seven albums during his career, the most recent one “A Flying Dog” in 2021, which earned him a 2022 Golden Melody Award, announced on July 2, for best male Mandarin singer. The album was also nominated for album of the year, best Mandarin album, and best album recording.

That ability to create and produce highly popular and recognized works at his age in the Chinese-language music community is exceedingly rare.

His staying power reflects his maturity and his sophisticated brand of rock ‘n’ roll that fuses Eastern, Western, folk and traditional instruments and the electric guitar accompanied by a unique hip-hop style.

“The caliber of Cui Jian’s works is on the level of Bob Dylan’s. Their stature and artistry have set the standard for Chinese rock ‘n’ roll,” said Rock Records (China) deputy general manager Ye Yun Fu.

In his title song on his latest album “A Flying Dog”, the lyrics begin with: “Sitting in front of the computer like a dog, the digital world a huge grassland where people cash in on information. A thought comes flying by as though traversing time of me and the grassland marching against the tide.”

Cui has never explained the symbolism in the lyrics, but according to Yeh, “the album A Flying Dog represents the existence of a type of alienation in contemporary times. The idea is not easy to understand, but someone has to express the idea.”

Yeh argued that pop music should be completely inclusive, able to range beyond superficial commercial hits to embrace classic works by artists like Cui that reflect the times.

Finding opportunities

Cui disappeared from people’s television screens for a long period of time, but in his words, “I never stopped performing,” preferring venues such as theaters, small performing arts centers, live houses, and music festivals to more mainstream arenas.

“The audience at a venue comes because of you and leaves because of you,” Cui said.

He cares about what fans think of his music rather than how many show up. “With the online concerts, some people may have paid attention to me simply to be part of the event, a lot like in the past when people started to like me because I was in vogue. There may be fewer than a million real fans who like me not because of a fad but because they have seen how I have evolved and pay close attention to things about me. Those are the people who really move me.”

Yet his absence from TV screens was never because of hostility toward the medium, and in 2015, he was back on television for the first time in years, taking part in the popular variety show “Singer” and then recommending contestants for the show “China Star”.

“I’ve never had negative feelings toward variety shows,” said the singer, now often called “Old Cui” by his fans. The reason, he said, is that before he shot to stardom with his debut performance of “Nothing to My Name” at the Beijing Workers’ Stadium in 1986, he was first noticed by well-known celebrities Wang Kun and Li Shuangjiang on a popular singing competition show a year earlier.

“Everyone should take advantage of opportunities to express their true selves,” Cui said. It was because the show’s judges were impressed by “this young man who can sing his own songs” that he was invited to the 1986 “Year of International Peace Concert” at which “Nothing to My Name” was unveiled, which led to his first record contract and the title the Godfather of Chinese rock ‘n’ roll.

Despite his fame, Cui has never felt deserving of the “Godfather” title and often feels dissatisfaction with himself.

He uses the mental gym in his head to deal with those struggles, his self-doubt like free weights to be lifted away. “Because I’m not satisfied, I want to lift barbells and do pull-ups. The greater the doubts, the more weight I add, so that when I stand up, I can be stronger than others,” he said.

Even though Cui’s hair is graying, he continues to sport the same red star cap and harbors the same doubts and thought process, searching for solutions to problems.

Outsiders may see Cui as someone who can knock off edgy songs critical of present-day issues with ease, but in reality, those songs are the product of long nights of carefully pondering and tweaking his words.

The glacier-like pace of his album releases are precisely because of Cui’s exacting nature. Unable to find an appropriate sound engineer to work with on “A Flying Dog”, he decided to learn mixing and recording himself and took nearly two years to complete the album’s production.

People often use the word “persistent” to describe the rock superstar, and some evensee his shouldering of the rock ‘n’ roll banner in China as an ordeal. Old Cui disagrees with those terms.

“You can’t say that rock ‘n’ roll is a form of ‘persistence,’, because that implies a kind of hardship. I enjoy what I’m doing,” Cui said.

Part of that enjoyment comes from not treating creation as a means to survive and not

having to change himself to cater to market demands.

This rigorous approach to writing songs, however, makes it hard for the artist to be noticed in a consumer age that prizes style over substance, which is why the recognition from the Golden Melody Awards, the top music awards in the Chinese-speaking world, was meaningful to Cui.

Cui told CommonWealth that if he were to win an award, he would “feel warm encouragement.”

After being named best male Mandarin singer, Cui reflected on his long journey and the future in a message read for him because he did not attend the Kaohsiung award ceremony in person.

According to a CNA translation, he said: "This album represents a journey for me with many stops along the way. Winning this award doesn't mark the end of the road but rather a crossroad marking the next step into what I realize now is a world of endless musical possibilities.”

Have you read

- Sound tripping: The life of a vinyl record transcriptionist

- Taiwan: a photographer's paradise?

- Blue ribbons: A riverside guide to Taipei

Translated by

Luke Sabatier

Edited by TC Lin

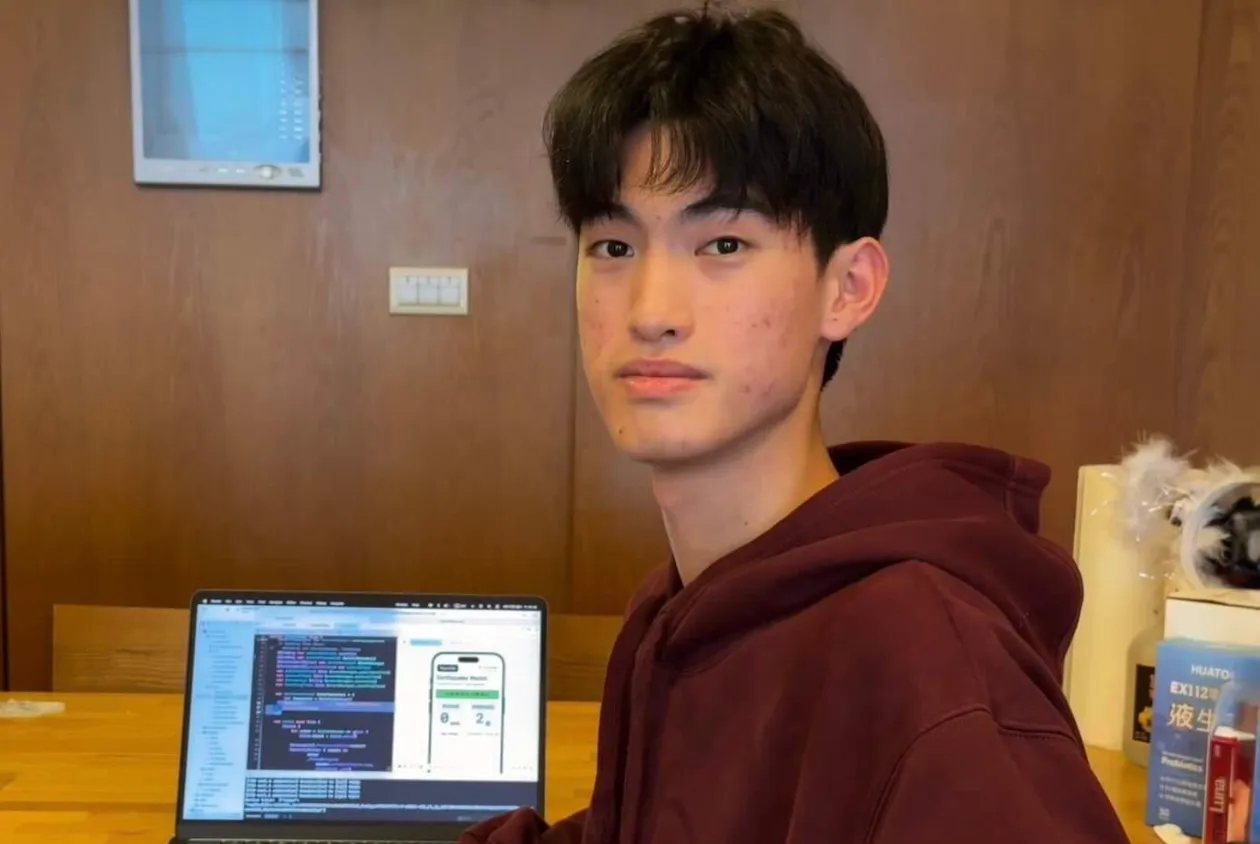

Uploaded by Ian Huang