What comes after Taiwan’s #MeToo moment?

Source:CommonWealth Magazine

At the end of May, a young woman launched Taiwan's #MeToo movement with her personal account of being sexually harassed while working with the ruling party. Over the following weeks, more than 100 victims, mostly women, have come forward to accuse prominent figures in politics, the arts, academia, and civil society of sexual harassment and abuse. More are expected to follow suit.

Views

What comes after Taiwan’s #MeToo moment?

By Ian Huangweb only

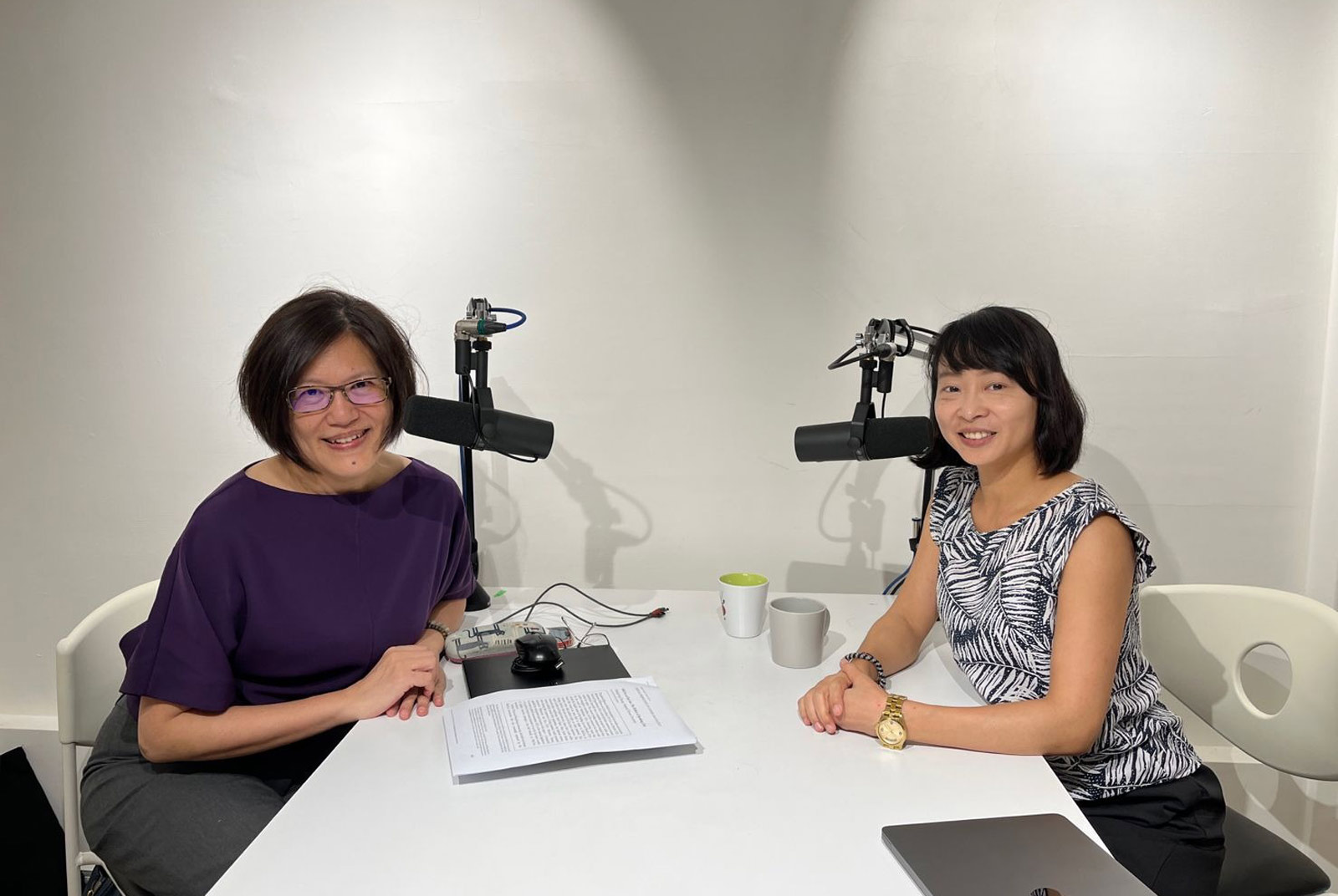

The following is the transcript of the seventh episode of the Taiwanology podcast. It was produced by CommonWealth Magazine, hosted by Kwangyin Liu, and was first aired Jul. 25, 2023.

Listen to the episode:【Taiwanology Ep.7】What comes after Taiwan’s #MeToo moment?

To start off the discussion, CommonWealth hears a first-person account from Lynn Chen. She is a film director from Taiwan.

A call for change

My name is Lynn Chen, and I have been a filmmaker in Taiwan for 20 years.

I have directed feature films, short films, documentaries, commercials and music videos.

12 years ago, I was hired to shoot a campaign advertisement in Kaohsiung, by the former mayor’s Chief of staff, Hong Chi-kun. It turned into a nightmare.

One day, the mayor's team claimed they couldn't book a business hotel for me, and, without my knowledge, put me in a motel instead. They also rescheduled the meeting to late at night. That evening, Hong came to my room for a meeting, but then he asked me strange questions like, "How much funding do you need to start a personal studio? I can help you."

Later that night, he tried to hug me and touched my breast. I kept my distance, and I saw him touch himself under the blanket.

“I was terrified. The next thing I remember is making excuses to go to the bathroom, trying my best to delay and avoid him. I didn't sleep the whole night until he left in the early morning.”

Shortly after that, I lost that job.

I was not even 30 years old at the time and didn't know how to speak up. It took me over a decade to find the language to say that I had experienced sexual harassment by someone in power.

I'm choosing to speak out now because it feels safer, and I hope to help others to come forward. After going public, I faced threats of lawsuits, online attacks, and PTSD episodes.

Many victims messaged me their stories privately.

I also witnessed the MeToo movement in Taiwan gaining momentum. Two weeks later, women in the film and television industry started to share their experiences, while most of the male-dominated industry remained silent. So I decided to express support and joined their groups, providing information and assistance when needed.

Exposing the scars is painful, but it's a start to ensure that everyone's experiences can be heard. I hope that the courage of individuals sharing their stories will contribute to making Taiwan society better, so that such oppression and crimes don’t occur in the future.

Kwangyin Liu: Almost six years after the #MeToo movement broke in the U.S. and Europe, Me Too now has taken Taiwan by a storm, sending shockwaves through the country as it prepares for a presidential election next January.

Some might say it all started with the popular Taiwanese drama series, Wavemakers, 人選之人造浪者, produced by Netflix, which drew parallels to real-life events. In the story, a young female staffer working for a political party encountered workplace sexual harassment. As her male supervisors tried to sweep her complaint under the rug, she had the support of a senior female colleague. Her line in the drama series, “we're not going to just let it go, okay?”. Became a common thread connecting the numerous accusations that have appeared online over the past few weeks.

Join us as we find out why some call this Taiwan's Me Too moment while others do not agree. What kind of consequences will there be for the victims and the accused? And what implications will there be for Taiwan's gender equality? Joining me today is Dr. Leticia Nianxuan Fang, associate professor of National Chenchi University's College of Communication. Her research topics include digital sexual violence, misogyny, and gender equity issues in Taiwan.

So let me ask you this question, Dr. Fang. We were talking before the show about Amber, the first young woman who came forward and launched Taiwan's Me Too movement. She inspired dozens of others to come forward, such as Lynn, whom we just heard from.

CW: What do you think about Amber’s case? Why do you think she was able to launch the Me Too movement in Taiwan?

Fang: Amber's case is exceptional because her post contains names, places, organizations, titles, and detailed interactions – essential storytelling elements. It's not fiction; this recent, real-life account had a profound impact on society. Its occurrence within the political realm, specifically the dominant political parties, amplified its significance. Amber's bravery in sharing her genuine experience left no room for the public to ignore. This revelation disrupted norms and highlighted the matter's urgency, making a lasting impression on society.

CW: It has all the facts, names. And also you have an organization that's trying to put this aside, ignoring her needs.

CW: So I guess many people are asking, what is the Me Too movement? How did it all start?

Fang: In 2017, American actress Alyssa Milano initiated the Me Too movement on Twitter following the Harvey Weinstein scandal, urging individuals to share their experiences of sexual harassment using the term "Me Too." This term was originally coined by activist Tarana Burke a decade prior and gained worldwide traction as a viral hashtag. While this movement led to protests and demands for rights, East Asia, including Taiwan, showed a lack of similar clarity in experiences.

Professor Huang Chang-Ling, affiliated with the political science department at National Taiwan University, conducted comparative research revealing that women were more likely to participate in the Me Too movement in countries with stronger political rights. Surprisingly, this didn't seem to apply to East Asian nations like Taiwan. Despite Taiwan's progress in legalizing same-sex marriage and having relatively high women's political representation, a Me Too movement failed to materialize.

In 2018, Taiwanese activists and feminists questioned the absence of a Me Too movement in the country, even as news headlines mentioned a "Taiwan version Me Too movement." However, no cases emerged that could truly catalyze the movement. Professor Huang's research also highlighted how media in democratic nations like Taiwan hindered the movement due to gender insensitivity and lack of quality journalism.

Even though some women who shared their experiences of harassment were courageous, the media response was often skeptical and dismissive. Credibility of victims matters, but the way journalists and news media investigated these cases was equally crucial. In Taiwan, speedy news coverage lacked depth and persistence, preventing sustained attention and serious investigative journalism on individual cases.

In conclusion, the Me Too movement's impact varied across regions due to factors such as media attitudes, credibility assessment, and the overall social climate. Despite Taiwan's progressive stance on certain issues, the absence of a robust Me Too movement underscores the complex interplay between societal dynamics and the drive for change.

CW: I think maybe back then when it all started, the journalists or maybe the media organizations in Taiwan did not take it seriously enough. One reason could be that it's part of our job. We see it every day. Even within media organizations, there's a lot of Me Too harassment or even abuse happening. And it's been normalized by the society, therefore, in the media organizations, maybe the supervisors themselves were men, and maybe themselves were perpetrators. They just didn't think this has any merit.

Fang: Exactly. They just didn't think people would care about this because culturally, women have no voice and they're abused or harassed every day. It's just part of life. Deal with it.

CW: So I think female journalists like me, we have seen numerous cases and they are normalized. So maybe that's one of the reasons why the journalists did not take it seriously enough. So that's sad to admit, but I think this also says to us that this is a time for change.

CW: Why did it take Taiwan so long?

Fang: As you mentioned earlier in this program, the popularity of "Wavemakers" has sparked widespread discussions and engagement. Even those who were initially less informed are now watching and participating, sharing not only their ideas but also their personal experiences.

I was recently in a cafe, and I couldn't help but notice the conversations happening around me. Several tables were alive with discussions where people openly shared their daily encounters. It was intriguing to witness, and it was a rare sight to see women confidently sharing their workplace experiences with their male partners.

Interestingly, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, a group of four women from different backgrounds underwent a similar journey when they confronted incidents of sexual harassment. These women faced a daunting structural issue that plagued them. The feminist NGO "Awakening" commissioned director Chen Junzhi to create the documentary film "War of Roses," which gained significant acclaim. Recently, there has been a resurgence of interest and discussion surrounding this impactful film.

Nearly 25 years ago, in 1999, "Awakening," the feminist movement NGO, offered support to four women who had been sexually harassed. Remarkably, two of these women decided to file sexual harassment cases and emerged victorious. The subsequent documentary film was showcased on campuses, drawing considerable attention. Despite this, it didn't seem to catalyze a widespread movement across the island.

Digging into newspapers from 25 to 30 years ago reveals headlines highlighting instances of women facing sexual harassment in the workplace. Legislators raised their voices, urging the government to investigate such cases. While news reports shed light on these issues, they often concluded at the point of reporting, much like the present day. The incidents were acknowledged, and the experiences of countless women were recognized, yet little progress seemed to follow.

Regrettably, a pervasive skepticism regarding victims, mainly women, persisted. Some individuals cast doubt on their motivations, suggesting that perhaps they sought special treatment from colleagues or superiors and, when dissatisfied, resorted to filing complaints. Such perceptions propagated an atmosphere of doubt and dismissiveness around these cases.

CW: So what's different about our society now that maybe there is less skepticism or hostility against women who speak out?

Fang: Just recently, for the past month, there are just so many cases in different walks of life, not just in political parties, not just in art, the arena, the sphere of sports, higher education, it's just like everywhere. The general public simply cannot pretend that this kind of cases is just unique. They did not exist. They are everywhere, okay?

And people start to talk and share their personal stories. So we realize it's everyday lives. So, but still we're at a stage of witnessing, all these cases popping up.

But in terms of how to reform the laws, how, when the cases go back to the individual institutes like universities, like companies, how the people gonna follow the guidelines there, conduct the investigation and file the reports, we are still witnessing.

CW: We were just chatting before that so many organizations and companies are, suddenly they are faced with their employees voicing, harassment that happened to them and they just have no idea how to deal with them.

CW: You mentioned to the traditional Taiwanese culture is keeping women from speaking out about their experiences. So what's unique about this culture?

Fang: Slut-shaming, a pervasive issue, extends beyond Taiwanese culture; it's a global phenomenon, especially evident on the internet. Women, by societal expectation, bear the responsibility of emotional labor. This includes managing emotions to meet the emotional demands of work, maintaining an attractive appearance, and assuming a caring demeanor. This societal role even extends to academia, where female professors are often anticipated to display greater warmth.

The demand for emotional labor is present in various settings – interactions with colleagues, customers, clients, and at home. Consequently, women are stereotypically linked with emotionally demanding roles in Taiwan. Additionally, women tend to feel embarrassed or ashamed when discussing gendered roles and sexual matters. Sharing experiences of sexual harassment is particularly challenging due to the lack of vocabulary and concerns about perception.

When recounting harassment experiences, victims are required to provide detailed accounts, not vague descriptions. This unfamiliar terrain contributes to a sense of taboo or discomfort. The societal expectation that women should not embrace their sexualized identity further complicates matters. However, these scenarios are a part of daily life.

It's unclear if these sentiments are exclusive to Taiwanese culture. Nevertheless, the stories shared by victims reveal a pattern. Many describe feeling stunned, numb, and unsure how to react when faced with harassment. This reaction is natural, as victims aren't accustomed to viewing themselves as objects of sexual desire. Yet, this objectification appears to be an ingrained norm in everyday life.

CW: How is Taiwan's Me Too movement different from the movement in other countries, say Europe or the US?

Fang: In the current scenario, a movement is undeniably underway. At this stage, what we are witnessing is a surge of cases coming to light. However, the full impact of legal reforms and the response of various organizations, whether public or private, remains to be seen. Presently, it seems that we are primarily in the initial phase of the movement, where awareness is being raised.

In a previous interview on this topic, you highlighted the issue of cyberbullying against women who speak out in Taiwan. This phenomenon isn't unique to Taiwan; it's been observed in other Me Too movements, including Australia and the United States. Victims' credibility is questioned, personal information is exposed through doxing, and online harassment ensues.

In Taiwan, a similar pattern is emerging. Innocuous-seeming messages often mask curious and skeptical undertones. Victims are questioned about their timing and motives, sometimes implying they are riding a trend or fabricating stories due to their anonymity. This skepticism stems from a cultural perspective that previously downplayed sexual harassment as trivial and non-malicious, dismissing it as commonplace and a part of everyday life.

This trivialization masked the personal trauma inherent in such experiences. The prevailing attitude dictated that one should endure such incidents, as they were considered rites of passage. The adage "personal is political" rings true for feminists, but this viewpoint wasn't widely embraced. Society failed to see these experiences as political in the broader sense, relating to human rights rather than party politics.

Before the current wave, society often perceived these incidents as non-serious, brushing them off as part of daily life. This collective violence isn't confined to isolated instances but accumulates from seemingly harmless jokes, inadvertent touches, or comments on appearance. Compliments framed in a context of objectification, like calling someone a "real woman" with sexual allure, contribute to this continual form of violence.

The pressure to embody traditional femininity further exacerbates the issue. Conforming to notions of mildness, constant smiling, and avoiding confrontation are expected traits. This complex interplay of cultural norms, skepticism, and dismissiveness has perpetuated the cycle of violence and undermined the gravity of these experiences.

CW: So I think this is really a watershed moment where this kind of behavior that was considered nothing or considered normal before, people are realizing that it's not okay to do that. And we should have a different awareness.

CW: But is this MeToo movement also facing challenges or resistance in Taiwan? What's your observation?

Fang: Mainstream news media in our country often interpret provocative messages, particularly those that resonate with the public, as representative of overall public opinion. Consequently, they report on such messages on behalf of the general populace. This trend isn't limited to the present situation. A couple of years ago, there was a surge in cases of digital sexual violence, involving the creation of deepfake pornography using images of female celebrities. These explicit videos were then used to attract paying members and were widely circulated online.

In response, NGOs and legislators called for amendments to criminal and civil laws to combat this form of violence. However, at that time, news media selectively focused on these cases and juxtaposed them against instances of murder, thereby fostering a dichotomy between gender-based violations and other criminal acts.

For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, there were instances of individuals disregarding mask mandates in convenience stores and resorting to violence, injuring or even killing store clerks. While these cases did occur, news media often presented comments from internet users suggesting that the emphasis on reforming laws to address gender-based violence should shift to focus on these murder cases, seen as more pressing and deserving of attention.

The current situation mirrors this tendency. With the influx of MeToo cases, there is a growing sentiment among the general public that it's time to move on from this issue. Many feel that the extensive coverage and awareness have reached a saturation point, leading to a call for shifting attention to other matters. This sentiment underscores the challenge of sustaining momentum for reform and addressing systemic problems, especially when public attention begins to wane.

The challenge or resistance in Taiwan lies in our tendency to consume cases without delving into finding real solutions for those who have experienced trauma, regardless of their gender. The sheer volume of emerging cases each day does not automatically equate to resolution when they are shared.

It's incumbent upon the media, both mainstream outlets and influencers, to take an active role in pursuing these cases. Thorough investigative reporting is essential to unearth the underlying structural problems. We are not just passive consumers of information; we are the ones who feel the call to drive reform. This responsibility falls on everyone's shoulders, but it's all too easy to merely acknowledge the information and move on, thinking the case is closed. Transitioning from awareness to tangible action is essential.

Regarding legal reform, there have been significant changes following the MeToo movement in the United States. While federal-level success might be limited, there has been substantial progress at the state level. Between 2017 and 2022, more than 2,000 MeToo-related bills were introduced at the state level, with roughly one-tenth of them being passed into law. These laws specifically focus on sexual harassment issues, including topics such as anti-harassment training and accountability for government officials.

The media's focus on high-level perpetrators and sexual misconduct mirrors the legislative developments, as both reveal crucial information. However, the key lies in follow-up actions. Combining increased awareness with meaningful legal reforms has the potential to completely reshape the gender landscape and rewrite societal norms. This holistic approach aims to create an atmosphere conducive to lasting change.

CW: Are we expecting to see any legal changes in Taiwan?

Fang: At the beginning of July, the central government is actively working on reform efforts, holding hearings and meetings day and night. Their goal is to reform gender-related laws, including anti-harassment and gender equity laws in campuses and workplaces, with an expected completion by the end of the month.

Despite past attempts by feminist scholars and NGOs, previous calls for law reforms yielded limited effects. This time, there's hope for more substantial change, especially in workplace gender equality laws. As MeToo cases continue to emerge, what changes can we expect in Taiwan? The transformation is gradual, aiming for safer and more equitable workplaces, where harassment is addressed and accountable. This shift signifies progress towards real gender equality, fostering a culture of respect and empathy in daily interactions.

A friend of mine received a message from her ex-boyfriend, reminiscing about a time when she shared her unsettling experiences of being sexually harassed on campus and at work. He admitted he didn't know how to react at the time, torn between believing her and lacking personal understanding of such emotions. He acknowledged that he simply listened, hoping their sharing could lead to something more. He recollected this as his response to his girlfriend's emotional sharing.

However, he recently wrote her a letter, expressing a newfound comprehension. He now fully understands, as the MeToo movement has shown him that such experiences are not isolated incidents but a pervasive part of almost every woman's daily life. He was struck by the realization that this issue goes beyond individual cases, and he offered a sincere apology. He's committed to making amends and actively listening, seeking ways to contribute.

This story holds immense significance. While legal reforms, new narratives, and shared experiences play their parts, what truly matters is the realization within the general public. It's not just distant stories; it's intolerable acts happening to people around us. This awareness fuels a sense of urgency to take action and be a part of the solution, rather than mere bystanders. This sense of collective responsibility and empowerment is vital, underscoring the power of this movement.

It demonstrates that even with thousands of voices speaking up, without genuine change in public perception, then this movement has no meaning and has no impact.

Have you read?

- An international perspective on Taiwan’s quest for gender equality

- From the Island of Women to #MeToo

Uploaded by Ian Huang