The fight in Taiwan for better migrant worker conditions

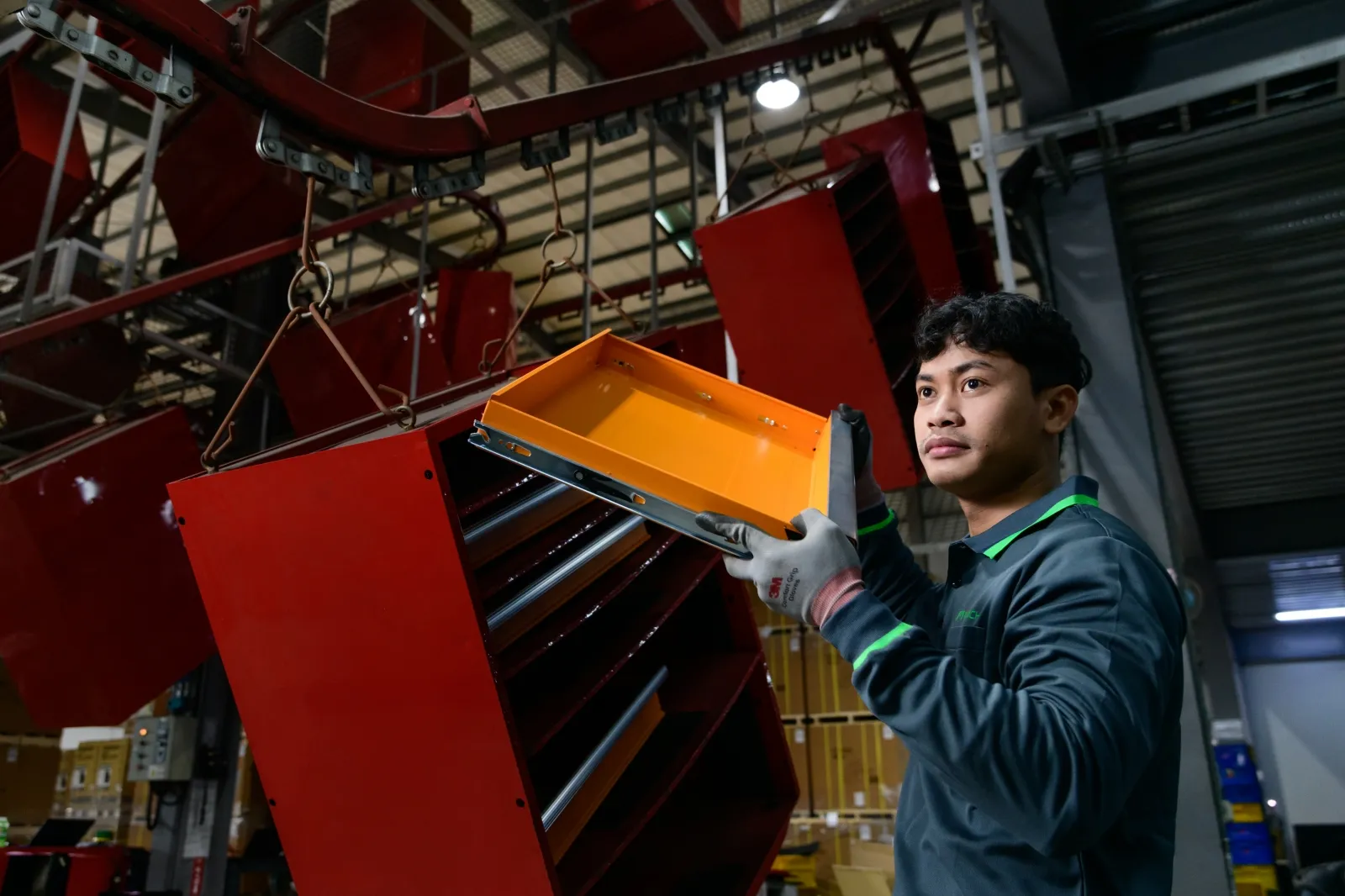

Source:Pei-Yin Hsieh

Often burdened by heavy brokerage fees needed to get and keep their jobs, some of the 750,000 foreign workers employed in Taiwan feel pressure to leave their legal employers to make ends meet. How seriously is Taiwan taking the challenge?

Views

The fight in Taiwan for better migrant worker conditions

By Liao Yunchan, Kwangyin Liuweb only

On a chilly Sunday, a group of Vietnamese workers sit on the floor of a Taoyuan residence enjoying typical Vietnamese dishes: deep-fried spring rolls, Bánh cuốn (Vietnamese rice rolls) and Bánh chưng (a cake of glutinous rice, pork, mung bean and seasonings). They’re in a festive mood, at times raising their glasses and calling out “một, hai, ba, dô!” (one, two, three, bottoms up!).

One of those on hand was spiffily dressed 32-year-old Phạm Minh Phương, who was in Taiwan to visit Taiwanese manpower brokerage agencies on behalf of his mother’s manpower agency in Vietnam.

His mother, Pham Thảo Vân, was Taiwan’s best known “absconded worker” (workers who leave their place of legal employment, in effect losing their legal status in Taiwan). In 2004, she paid US$8,000 in brokerage fees to work in Taiwan as a caregiver. Three years later when her contract was not renewed and her manpower agency did not help her find new employment, she decided to stay illegally in Taiwan rather than return to Vietnam.

Phạm Minh Phương (front), the son of a fugitive migrant worker, grew up only being able to follow his mother, who ran away in Taiwan. When he grew up, he ran an agency with his mother. (Photo: Chien-Ying Chiu)

Phạm Minh Phương (front), the son of a fugitive migrant worker, grew up only being able to follow his mother, who ran away in Taiwan. When he grew up, he ran an agency with his mother. (Photo: Chien-Ying Chiu)

During her 11 years in Taiwan as an undocumented worker, she became an opinion leader in the Vietnamese worker community. She arranged 128 farewell ceremonies for compatriots who had lost their lives in a foreign land and carried urns with their ashes 30 times to the airport to send them home.

“I didn’t want to go on the run, but I had no choice,” Pham Thảo Vân recalled, her eyes reddening.

Whatever money she earned in her first three years in Taiwan went to brokers and to her younger brother who was ill, with nothing left to help her father take care of his medicine bills, and she decided to gamble.

“If I had returned to Vietnam at that point, I would have gone home without a penny,” she said.

After working in Taiwan outside the legal framework for 11 years, this Vietnamese migrant worker returned home to open her own manpower agency, a rather dramatic development in Taiwan’s migrant worker history. She believed that Vietnamese migrants would be treated better if she were a labor broker.

Human Rights ‘Supply Chain’ Taking Shape

Today, Pham Thảo Vân has the backing of an international human rights “supply chain” that is helping forge positive changes in the working environment of Taiwan’s 750,000 migrant workers, starting with the manufacturing sector.

One part of that chain will be Europe.

Europe’s “due diligence act will be like the new CBAM,” predicted Aleksandra Kozlowska, head of the trade section of the European Economic and Trade Office.

The CBAM, Europe’s “carbon border adjustment mechanism,” prices carbon in imported goods, and Kozlowska believes Europe’s new initiative on human rights will have as much of an impact as its global carbon reduction initiative.

Human rights have emerged as the new focus of global supply chains, with many of the main clients of Taiwanese goods in Europe and the United States putting more emphasis on the issue. Once a moral issue that companies could elect to stress or ignore, human rights are now poised to become a legal issue that can no longer be avoided.

At the end of 2023, the European Council and European Parliament reached a provisional deal on the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive. It stipulates that companies have the responsibility to manage and conduct due diligence on their supply chains to prevent adverse human rights and environmental practices, such as child labor, forced labor, or pollution generation. The EU plans to enact the directive’s legislative framework and have it take effect as early as 2026.

The United States has also launched a “Global Labor Strategy” to crack down on activities that hinder workers’ rights, such as forced labor or bans on unions.

Sam Lin (林泉興), founding member of KPMG Sustainability Consulting Co., Ltd., explained the consequences of the EU directive. If Taiwan’s supply chain is determined to be a forced labor risk, it will not be able to take orders from EU clients, and Taiwanese companies will not be able to buy raw materials or components from EU countries, endangering roughly 60 billion euros in trade, he said.

EU investors would also not be allowed to invest in Taiwanese companies.

The cruel truth for Taiwan is that it has been cited by major brands such as Apple and Cisco as a country at high risk of forced labor.

Taiwan Labor Practices Cited by Apple, Cisco

In 2015, Apple began prohibiting foreign workers employed by its suppliers from paying fees connected to their recruitment or employment. In its 2022 annual progress report on “People and Environment in Our Supply Chain,” it said it conducted assessments of facilities employing migrant workers (called foreign contract workers by Apple) in Japan, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam, and the United Arab Emirates. Only in Taiwan did it discover two cases “where people paid recruitment fees to secure their job, which is a violation of our Code.”

Citing laws in Taiwan and Malaysia that allow fees to be collected from migrant workers, Cisco said special attention needed to be paid to forced labor risks in those two countries. It also demanded that four suppliers return fees to workers.

In its 2022 Sustainability Progress Report, Jabil, the world’s third largest electronics manufacturing services provider, cited Taiwan as one of 10 regions considered “high-risk” for human rights, along with China, Brazil, India, and Malaysia, among others.

Another source highlighting Taiwan’s risks is Bonny Ling, the Taiwan-born executive director of Work Better Innovations and nonresident senior fellow with the University of Nottingham Taiwan Studies Programme.

She listed some of the issues in a report she compiled in 2022 titled “Understanding the International Labour Organization Indicators of Forced Labor,” which was based on the ILO’s 11 indicators for forced labor.

The guide, intended for Taiwan’s small and medium-sized enterprises, said a few employers in Taiwan withhold migrant workers’ wages to have them cover such expenses as physical checkups and plane tickets and pay for “legally permissible monthly service fees” that go to labor brokers. These are all seen as forced labor risks, according to the report.

It also noted regular abuses in China, such as excessive overtime, poor working environments, and controversy over Uyghur re-education camps in Xinjiang.

Only Market with Monthly Service Fees

The “monthly service fees” collected by brokers are a particular point of contention.

Taiwan’s government prohibits domestic brokers from collecting brokerage fees from overseas workers, but they are still allowed by law to charge “monthly service fees” if services are actually rendered. A 2022 report by the United States State Department found that foreign workers still generally faced exploitation due to excessive brokerage fees, leaving workers “vulnerable to debt bondage.” In effect, the monthly service fees were simply another name for notorious “brokerage fees.”

“I did a comparative study of many countries, and Taiwan is the only country that has a law stipulating that migrant workers pay service fees to brokers,” Ling said, worried that such a law was a warning signal for coerced labor.

The Taiwan International Workers' Association (TIWA) has been organizing biennial rallies for migrant workers' rights since 20 years ago, and in recent years has been calling for direct government-to-government hiring, downplaying the role of intermediaries. (Photo: Rongrong Zhang)

The Taiwan International Workers' Association (TIWA) has been organizing biennial rallies for migrant workers' rights since 20 years ago, and in recent years has been calling for direct government-to-government hiring, downplaying the role of intermediaries. (Photo: Rongrong Zhang)

Steven Hung (洪昌吉), president of one manpower brokerage, K.D. Manpower International, disagreed.

“Calling this forced labor is going too far. Human rights groups are manipulating this,” he said, arguing that migrant workers come to Taiwan of their own volition and that service fees are part of the law.

There is one issue on which scholars and brokers agree, however: that brokers should collect service fees from employers rather than foreign contract workers. Though employers do currently make some payments to these intermediaries, migrant workers often have to pay 10 times as much.

Solving these problems require urgency, not just for workers but for Taiwanese employers. As Japan and South Korea open their doors to migrant workers, Taiwanese companies, desperate to recruit people from global labor markets, cannot afford to wait interminably for laws to improve.

Pham Thảo Vân (right), was Taiwan’s best known “absconded worker” and her son Phạm Minh Phương. (Photo: Phạm Minh Phương)

Pham Thảo Vân (right), was Taiwan’s best known “absconded worker” and her son Phạm Minh Phương. (Photo: Phạm Minh Phương)

Quiet Church Revolution

One Sunday morning, more than 300 migrant workers from the Philippines attend mass at Tanzi Roman Catholic Church in Taichung. New parents have brought their baby to be baptized by priest Joyalito Tajonera.

Father Joy as he is known has been a staple there for the past 25 years, and his Catholic parish is more than just a meeting place for the faithful; it is a sanctuary for overseas workers in the area. Above the chapel is a shelter for migrants that cares for those who are unemployed or unwell.

Because of his dedication to care for migrant workers, Father Joy even spends time at the end of his masses talking about labor trends in Taiwan and abroad.

He has made impressive inroads in helping his parishioners, teaming up with New Jersey native Charles Niece over the past four years to help 2,500 Filipino workers in Taiwan recover more than NT$120 million in brokerage fees or their confiscated passports.

Joyalito Tajonera. (Photo: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

Joyalito Tajonera. (Photo: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

In 2019, he noticed that many Taiwanese tech companies had joined the U.S.-based Responsible Business Alliance (RBA). It promoted a “no-fees” recruitment policy, which said workers should not have to pay any fee to get a job.

Most importantly, the policy went from being “suggested” to “compulsory” for members. Major brands such as Apple, Amazon, HP, and Dell and more than 20 Taiwanese companies, including TSMC, Acer, AsusTek and Compal Electronics, are all RBA members.

Long Detour Turned into a Shortcut

That gave Father Joy and Niece the leverage they needed to pressure companies on the issue. Over the past four years, companies that have joined the RBA have all restituted the brokerage fees paid by their overseas workers.

Three years ago, Niece assisted a foreign worker, employed by a Japanese factory, in raising a complaint about their dorm room's cramped conditions, likening it to a 'pigeon cage. Noting that the company was an RBA member, he directly notified the RBA’s American headquarters of the problem rather than contacting the company.

Though it seemed like a roundabout approach, it was actually very effective, as a major American client took up the issue with the Taiwanese employer.

“One word from a customer is much more effective than a protest by 100 workers,” Niece said.

In the three years since, he has helped migrant workers communicate their problems to Amazon, Jabil and HP and received positive responses. Through that role, he has emerged as the key contact for communications between the RBA and Taiwan’s migrant worker community and has even been invited by the group to talk about Taiwan’s experiences.

“This is a grassroots movement started from the ground up, and more and more people believe they have power,” Niece said.

Human Rights a Competitive Barrier

Despite the good intentions, investing in carbon reduction and absorbing the various fees of migrant workers have imposed heavy costs on the supply chain and created a new competitive barrier.

“Purchasing departments want your prices to be cheaper and delivery to be faster, but audit departments demand that you comply with labor standards, which can be contradictory,” complained a business owner.

When clients demand standards that even exceed statutory requirements, they are for all practical purposes intervening in companies’ corporate governance and should assume some of the responsibility for their demands, said Chang Wen-chi (張文祈), a master of law from National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University whose main thesis was on forced labor

“Overseas clients often make requests of suppliers that are contradictory,” said Chang, and brand clients and suppliers should share the burden. Those with more resources should help vendors in their supply chains defray some of the costs associated with improving human rights practices, she said.

At present, however, Taiwan’s supply chain is on the hook for all costs associated with strengthening human rights. Some companies have decided to fully shoulder the responsibility.

Powertech Technology Inc., the world’s biggest memory chip packaging provider, spent six years optimizing its direct recruiting system, and now over 80 percent of its overseas workers are hired without the use of brokers.

Filter specialist Taiwan Grace International Corp. got the jump on its clients, voluntarily paying brokerage fees on behalf of their workers the first time it hired overseas workers.

Ling praised the efforts of these companies to improve the lot of migrant workers, but acknowledged that no country to date fully complies with the “employers pay” principle. She believed, however, that Taiwan could take the lead on this issue.

Japan, South Korea Quick to React

Amid the trend toward a greater emphasis on workers’ rights, Taiwan’s government, despite maintaining the onerous monthly service fees, has tried to improve the human rights environment for overseas workers in other ways.

Minister without Portfolio Lo Ping-cheng (羅秉成) said one action taken in Taiwan was under the government’s human rights project for the fishing industry. The Ministry of Agriculture addressed the controversy over the rights of deep-sea fishing crews by rolling out a “Suspected Labor Trafficking of Foreign Crew Member Examination Chart” based on the ILO’s 11 indicators of forced labor.

This year, the government drew on Japan’s experience to release a new version of Taiwan’s updated national plan on companies and human rights, he said.

The next goal, according to Lo, is to apply the chart to migrant workers employed in domestic businesses and help companies better align themselves with international standards.

These actions are essential not simply because Taiwan needs to keep up with global labor standards. It also has to reconsider its attractiveness to foreign workers given the competition for people faced from Japanese and Korean employers.

“I tell clients that ‘you used to treat migrant workers like slaves, but now you have to respect them as workers,’” said K.D. Manpower’s Hung, who indicated that the thinking of employers is changing.

Once the rights of migrant workers are protected, and the risk of forced labor no longer exists, the hope is that these workers will no longer feel cornered into leaving their employers to take on undocumented jobs, and that Taiwan will no longer be seen as being at high-risk for forced labor.

Have you read?

- Is Taiwan foreigner-friendly? They have something to say

- Allow new residents to take root in Taiwan

- Progress Begins from Within. An International Taiwan is in Reach

Translated by Luke Sabatier

Uploaded by Ian Huang