Taiwanese Folk Art Paper Funeral Offerings on Display in France

Source:Ministry of Culture

Paper creations often seen at Taiwanese funerals carry blessings for the dead, but the taboos associated with them can keep people away. Why have these traditional crafts appeared twice in recent years in museums in Paris and led French visitors to marvel at how “romantic” they are?

Views

Taiwanese Folk Art Paper Funeral Offerings on Display in France

By Monica WangFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 678 )

Sitting on the banks of the Seine not far from the Eiffel Tower is the Musee du quai Branly, which exhibits collections of multicultural art and artifacts from Asia, Africa and Oceania.

From now until October, visitors who stroll into the museum’s Atelier Martine Aublet will come upon a papier-mâché house for the dead, but there’s no reason for alarm. This folk ritual staple is part of an exhibition called “Paradise Palace – Paper Funeral Offerings in Taiwan” that has been put together by museum curator Julien Rousseau, the Ministry of Culture’s Centre Culturel de Taiwan a Paris, and the Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts.

This eye-catching handmade house currently on display in France resembles a traditional temple. Its structure, which has a front but not a back, symbolizes looking ahead rather than back to the past. (Source: Hsin Hsin Paper Offering Store official Facebook page)

“The French are very surprised at how paper can be used to make houses and things that look so much like the originals, and they think it is very romantic that in the end all of these paper offerings are burned,” says Tseng Fang-ling, the head of the Exhibition Department at the Kaohsiung museum, with a chuckle.

Tseng was referring to the main function of these paper creations. After appearing at funerals they are burned to ensure the material comfort of the deceased in the afterlife

This is not the first time these paper offerings have been displayed in France. Three years ago, curator Patricio Sarmiento discovered this mysterious and sophisticated craft while traveling in eastern Taiwan, and he invited the Hsin Hsin Paper Offering Store to participate in the D’Days Festival at the Louvre’s Department of Decorative Arts.

Century-old Craft across Four Generations

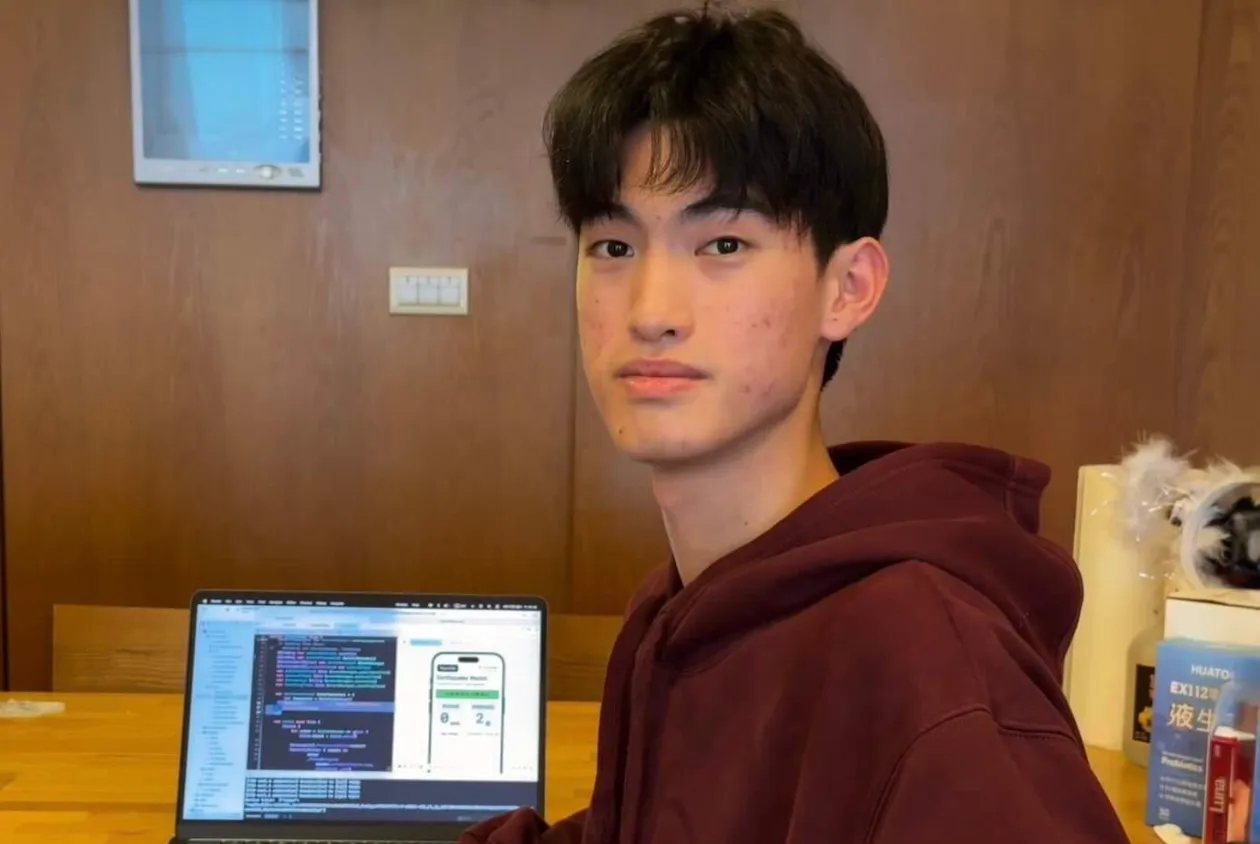

The craftsmanship so admired by the French has come in part from the hand of Hsin-Hsin master Chang Hsu-pei, who started learning papier-mâché skills from his grandfather at the age of 14 and studied with many other old masters along the way. His works have appeared at both the Louvre in 2016 and at this year’s show.

Enter a small alley next to Filmmate Cinema in Xinzhuang in New Taipei and one comes upon a rusty metal door. Inside, the nearly 70-year-old Chang sits on a stool only 15 centimeters high as he has for the better part of his nearly 60 years practicing his craft. That day, he is toiling over the bamboo frame of an offering for ghost month in July on the lunar calendar that he needs to quickly deliver. His daughter Chang Wan-ying is at his side helping out, while a papier-mâché modern villa to be delivered that night sits behind them.

Chang Hsu-pei represents the third generation of his family’s century-old paper funeral offerings business. He began learning papier-mâché skills at the age of 14 from his grandfather. (Photo by Ming-Tang Huang/CW)

The Changs’ utterly commonplace living room carries the blessings and feelings of longing countless people have asked Chang to help them express to the dead. The tools of the trade accumulated over a century are all on display, including cutting and binding bamboo struts and cutting delicate decorations and sticking them together.

“My grandfather’s strengths were figures and painting. When he was 90 he was still painting lifelike figures,” Chang said.

Chang’s grandfather, Chang Gen-chi, who was better known as “Master Chi” or “Papier-mâché Master Chi,” founded a store in 1895 called “Mao Hsin Chai” in Dalongdong, an old village in historical Taipei. Recalling his younger days, Chang said the family came in contact with affluent families and even received calligraphies and paintings by Li Hongzhang, who served in important positions in the imperial court in the late Qing dynasty.

Chang still remembers the family business working hard to ship orders with the help of 20 papier-mâché artisans, each performing the one step in the process that they were familiar with. It took Chang many years before he learned the entire process for making paper funeral offerings.

In fact, it took Chang two to three years just to learn how to cut the bamboo struts used for each object’s bamboo frame, a skill that requires an understanding of a bamboo’s structure and an excellent touch. His specialty is paper cutting, seen by the ease with which he cleanly cuts delicate decorations that can split apart even when being cut by the most precise laser.

Da Shi Yeh is an incarnation of Guanyin, the Buddhist bodhisattva associated with compassion. The blue face and fangs are designed to deter ghosts, which is why this is mostly used as an offering during ghost month. It was carefully transported to France for the exhibition. (Source: Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts)

Da Shi Yeh is an incarnation of Guanyin, the Buddhist bodhisattva associated with compassion. The blue face and fangs are designed to deter ghosts, which is why this is mostly used as an offering during ghost month. It was carefully transported to France for the exhibition. (Source: Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts)

Orders for Papier-mâché Objects Reflect Social Change

In 1990, “Mao Hsin Chai” was taken over by Chang’s brother Chang Chiu-shan, and Chang and his wife moved to Xinzhuang to start Hsin Hsin Paper Offering Store. The new store’s business was great because people were willing to spend on funerals as the economy picked up.

The customized orders the Changs received for paper offerings reflected the social change being seen in Taiwan. In early years, the traditional U-shaped courtyard homes had plenty of room, and funerals could be held within the confines of the home, allowing space for huge papier-mâché houses, figurines of a young boy and girl (representing a servant and maid), furniture, and vehicles. Later, buildings with elevators and electrical appliances began appearing as people’s requirements became increasingly modernized and personalized.

“There was one time when the deceased was a person who collected rent and his family hoped we could make a commercial office building with three elevators so that he could continue collecting rent without worries in the afterworld,” recalls Chang Wan-ying. Hsin Hsin Paper Offering has plenty of stories of well-known figures, from late businessman and diplomat Koo Chen-fu and late Shin Kong Group founder Wu Ho-su to today’s celebrities, asking for its help.

Urbanization and changing attitudes, however, sent the paper offering business into gradual decline, and it was even replaced in some quarters by products from printing machines. Chang Pei-hsu’s son, Chang Hsu-chan, recalls the situation getting so bad that there was a year in which it received only one order, and the family discussed whether it wouldn’t make more sense to rent their house instead of continuing with the business.

Have you read?

♦ Papercraft Artist Johan Cheng Cuts a Slice of Life’s Most Beautiful Moments

♦ Taking Taiwan’s Culture to the Runways of London and Paris

♦ Getting the Most from Ghost Month in Taiwan

Reversing Taboos, Moving into New Territory

“When I was young, I didn’t want people to know that my family was in the paper offering business. But when I grew up and saw this traditional art disappearing, I didn’t want that to happen,” said Chang Hsu-chan, an artist in his own right who has been nominated for a Golden Horse award for best animated short film.

After he enrolled at Taipei National University of the Arts, he reconsidered the meaning of paper offerings through an animated short film that drew widespread attention and recognition.

In 2013, the family and illustrator Juju Chan set up Hsin Hsin Joss Paper Culture. The new venture held exhibitions, opened a Facebook account, and launched a workshop, helping reverse taboos and biases. The family started receiving invitations to show their crafts, leading to their appearance in French museums. The amusing images of a papier-mâché rendering of a Western couple displayed at the Louvre and other locations received a huge response online and exposed the art to the younger generation.

Source: Hsin Hsin Paper Offering Store

Source: Hsin Hsin Paper Offering Store

Taiwan’s former representative to France, Michel Lu, who used traditional glove puppetry to market Taiwanese culture there, observes that France has developed a multicultural, free and open society without taboos, which has enabled it to better appreciate the beauty and cultural significance of Taiwan’s paper funeral offerings. (Read: Traditional Puppetry in Taiwan)

Promoting these papier-mâché works of art with religious significance has not been easy for the Chang clan, who have not raised prices for many years or pursued commercial success. Yet in remaining dedicated to their craft, they have opened new horizons for this old folk custom, helping it emerge from anonymity to be appreciated by the world.

Hsin Hsin Paper Offering Store Milestones

1895 Chang Gen-chi, Chang Hsu-pei’s grandfather founds papier-mâché store “Mao Hsin Chai” in Dalongdong.

1990 Chang Hsu-pei founds Hsin Hsin Paper Offering Store in Xinzhuang.

2013 Chang Hsu-pei receives a New Taipei master of traditional arts award Chang Hsu-pei, his wife Chang Chen Ah Kuan, Chang Wan-ying, Chang Hsu-chan, and Juju Chan establish Hsin Hsin Joss Paper Culture to promote traditional papier-mâché crafts and plan special Hsin Hsin Paper Offering exhibitions. It also sets up a “hsinhsinjosspaper” Facebook page on the enterprise and the art of making papier-mâché objects.

2016 Takes part in the D’Days Festival at the Louvre’s Department of Decorative Arts

2019 Displays its works in an exhibition called “Palace Paradis” at the Musee du quai Branly

(Left) This “Ti Tsang” bodhisattva is known for the compassionate salvation of ghosts. It is used as an offering, for worship, and to collect. (Right) Officials with their horses, used at temple festivals, are messengers who report on issues related to the people to the Jade Emperor. (Photo by Ming-Tang Huang/CW)

(Left) This “Ti Tsang” bodhisattva is known for the compassionate salvation of ghosts. It is used as an offering, for worship, and to collect. (Right) Officials with their horses, used at temple festivals, are messengers who report on issues related to the people to the Jade Emperor. (Photo by Ming-Tang Huang/CW)

Basic Process for Making Papier-mâché Offerings

Bamboo cutting, tying: Hand tool used to cut bamboo into struts, with are then tied fixed together using tissue paper to create a frame

Paper cutting, pasting: Little decorations such as clothes or roofs are cut and then glued together

Painting, sculpting: Figures, landscapes or other shapes can be painted using mineral pigments or sculpted with ceramics.

The decorations on the paper house are similar to animal stone carvings seen in European architecture. This horse symbolizes going full speed ahead and gaining success. (Photo by Ming-Tang Huang/CW)

Translated by Luke Sabatier

Edited by Sharon Tseng