Is Taiwan’s Pork Industry Up to the U.S. Challenge?

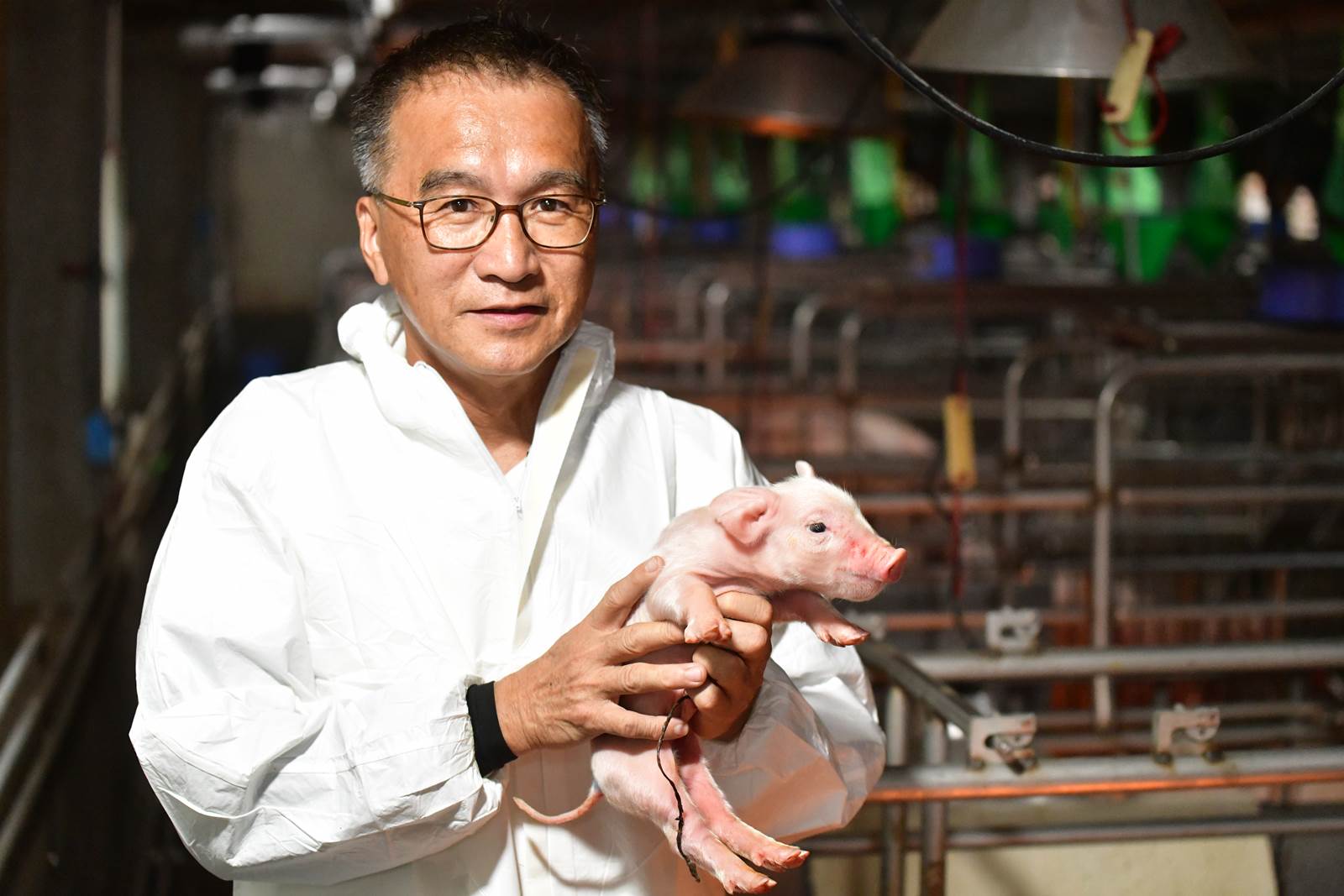

Source:Kuo-Tai Liu

Taiwan’s government has announced it will allow imports of American pork containing a banned veterinary drug. CommonWealth Magazine has taken an in-depth look at the domestic pork industry to see if it is up to the challenge and how the brand value of Taiwanese pork can be strengthened.

Views

Is Taiwan’s Pork Industry Up to the U.S. Challenge?

By By Laura Kang, Kuo-chen LuFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 707 )

It is four in the morning as a truck carrying freshly slaughtered pork slowly pulls into a local wet market, preparing for another day of peddling Taiwan’s most popular meat.

The average Taiwanese eats more than 36 kilograms of pork every year, with annual consumption totaling roughly 900,000 metric tons.

As important as pork is to local consumers, however, an administrative order at the end of August cast it as the pivotal factor in relations between Taiwan and the United States.

Hog Farmers Anxious with U.S. Pork at the Door

“This decision is based on our national economic interests and consistent with our overall strategic goals for the future,” President Tsai Ing-wen announced on Aug. 28, setting the stage for lifting a ban on imported American pork containing the veterinary drug ractopamine that had lasted for 19 years, spanning the tenures of three presidents.

The move, expected to take effect in early 2021, was made to appease the United States, which characterized the ban on imports of pork with ractopamine as an impediment to trade, and the hope that it will pave the way for a trade deal with Washington in the future.

But it still triggered considerable controversy revolving around political, economic and food safety issues, among them the potential for cheap American pork with ractopamine hurting Taiwan’s pig farmers.

In an assessment conducted in 2016, the government estimated that opening Taiwan’s market to U.S. pork containing ractopamine would cost the domestic hog-raising and pork industry NT$14.3 billion.

“From a macro perspective, when Taiwan reaches out into the world, there will absolutely be gains and losses….You can’t just look at the blow from American pork. They key is how our industry can thrive in the future,” said Council of Agriculture (COA) chief Chen Chi-chung (陳吉仲).

Soon after Tsai’s announcement, the COA proposed a NT$10 billion fund to cushion the potential blow of imported pork and attempt to strengthen the competitiveness of Taiwan-produced pork, reflecting a desire not only to battle U.S. pork at home but also enter foreign markets.

A major step was taken in June when the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) officially confirmed that the Taiwan, Penghu and Matsu areas were an “FMD (foot-and-mouth disease) free zone where vaccination is not practiced.” After a 23-year period under a cloud, Taiwan’s pork industry finally saw a glimmer of hope that it could once again export its meat.

After FMD, Pork Industry Stagnates for 20 Years

“Taiwan used to be Japan’s biggest source of imported pork, which was frozen meat. [Taiwan] had a geographical advantage that other countries couldn’t match,” said Kevin Wu (吳季衡), COO of Nice Garden Industrial Co., which created the pork brand “Choice Pig.”

Before foot-and-mouth disease surfaced among Taiwan’s pigs in 1997, Taiwan’s pork industry was on a par with Denmark today, with annual pork exports of about NT$46 billion. It capitalized on its advanced chilling and cold chain technology, keeping pork stored in temperatures below 7 degrees Celsius to maintain its freshness, to export the meat to Japan and other neighboring countries.

After FMD hit, however, exports were cut off, limiting Taiwan’s hog farmers to supplying the domestic market.

“Over the past 20 years, there have been no big investments or advances made,” said Charles Huang (黃育徵), founder of the Taiwan Circular Economy Network and a former chairman of Taiwan Sugar Corporation, which is involved in the livestock business.

As Taiwan’s pork industry remained stuck in time, competitors in the West caught up and became major pork exporters, including back to Taiwan. In 2019, its biggest sources of pork imports were Canada, Spain and Denmark.

Now, with U.S. pork knocking on the door and Taiwan’s own industry having stagnated for two decades, what can be done to turn the situation around and stabilize domestic demand for Taiwan-produced meat while encouraging exports?

CommonWealth Magazine visited hog farms, auction markets, slaughterhouses, food processing plants, and traditional meat markets to focus on the “warm-body pork” – pork that is never chilled or frozen – preferred by Taiwanese consumers and uncover the truth behind the decline of the domestic pork industry.

As a piece of pork makes its way from farm to market, is “warm-body pork” truly synonymous with “fresh” pork?

A Pork Journey

Taiwanese consumers most love eating “warm-body pork” slaughtered the same day. Seventy percent of the pork consumed in Taiwan comes from traditional markets, which sell pork that has not been chilled or frozen. Yet is it really fresh?

The answer may be no, said Lin Rong-shinn (林榮信), a professor in National Ilan University’s Department of Biotechnology and Animal Science, because pork in Taiwan is mostly transported to market in a room-temperature environment.

“The bacterial count tends to approach the critical threshold for rotting,” Lin warned, stressing that pork should be refrigerated during the transportation process to keep it fresh. But Taiwan’s consumers generally believe that only meat that is not fresh needs to be chilled or frozen, a belief that has been hard to change.

To cater to this demand for “freshness,” Taiwan’s nearly 60 slaughterhouses usually start operations at 11 at night and kill an average of 23,000 pigs a day that trucks rush to deliver to markets by 4 a.m.

CommonWealth reporters followed this life-to-death journey and found that Taiwan still had plenty of room for improvement in the process, from auction to slaughter, based on international norms.

One place where this plays out is the Hsinchu Meat Market, starting at around 1 p.m. when more than 700 pigs line up, ready to strut their stuff.

One sees a worker get each pig on the scale, and a screen displays the pig’s number and weight. Soon after, the pig is driven by a worker’s shouts and prodded by an electric goad through a walkway bordered by a metal fence to the auction area.

The auctioneer then calls out the reserve price and gives bidders a chance to check the pig’s appearance before they start to bid by pressing the bid button next to their seats.

“We’re like the stock market, offering a platform for people to buy and sell pigs,” said Wang Teh-hsin (王德鑫), the head of the Hsinchu Meat Market’s general affairs division. The price Taiwanese pay for pork at traditional markets is determined by these meat auctions and depends on the experience and eye of each buyer. Pigs that are leaner and longer and have wide shoulders, a big backside and a flat belly usually have leaner, less fatty meat and fetch higher prices at auction.

Live Auction System Out of Sync with Global Norms

After the pig is auctioned and marked, it is held in a fenced area in the back of the auction area and cleaned and given water in the final hours of its life before being slaughtered the same night.

Taiwan’s live auction system delivers the fresh, “warm-body” meat Taiwanese consumers prefer, but it is inhumane and cannot be easily aligned with the “carcass grading” system used internationally, which could make Taiwanese pork harder to export.

The carcass grading system relies on professionals and scientific instruments to gauge the length and width of the carcass, and the color, texture and marbling of the meat, which then determine its grade and price. The system standardizes the pricing process rather than leaving it up to subjective human judgments.

But changing the auction system would involve more than just taking on industry habits; it would also challenge vested interests.

At present, the profit on slaughtering a pig and dressing its carcass, is about NT$1,000 per animal. If the system is changed to carcass grading, profits earned on the slaughter and auction of the animals will be redistributed, and workers involved in transporting live pigs and the auction process could find themselves unemployed.

Also, if a slaughterhouse wants to upgrade its facilities, it must get HACCP (hazard analysis critical control point) certification. Only if it meets the comprehensive HACCP standard covering environmental hygiene, operating procedures, and equipment and facilities can it hope to export its product to demanding buyers.

But with Taiwan unable to export pork for more than 20 years, new plants will have to be built to meet the HACCP standard, and their price tag of at least tens of millions if not a hundred million Taiwan dollars could deter interest. At present, no Taiwanese slaughterhouse has obtained HACCP certification.

Companies such as Taisugar, Great Wall Enterprise and CP Foods have imitated Western management methods in their meat processing operations, integrating rearing, slaughtering and processing operations to expand their scale and develop internationally.

But as Charles Huang admitted, “we are small fry. It would be hard to surpass others.”

Turning to Computers to Raise Pigs

According to the Council of Agriculture, nearly 75 percent of the hog-raising farms in Taiwan rear fewer than 1,000 pigs, and these small and medium-sized pig farms lack the resources and manpower needed to upgrade their operations.

Huang recalls a visit to a pig farmer after taking over as Taisugar chairman that drove home the problem. He walked into the pig pen only to find that cats and dogs had jumped over the enclosure’s fence and were running around freely.

As much as the environments of traditional hog-rearing farms need to improve, the industry is beset by other external challenges. Taiwan’s hot and humid climate makes it harder to prevent infectious diseases and manpower remains in short supply, pushing costs higher.

Both the efficiency of Taiwan’s pig farms and their costs of about NT$65/kilo stack up poorly against pig-raising operations in the United States, but that has not stopped some breeders in Taiwan from trying to change.

Mike Chen (陳永雄), the owner of San-Yuan Farm (三源畜牧場) in Yunlin County, takes a visiting reporter into a new pig pen that is still under construction. The pen features a raised floor, a high ceiling and a fence made of stainless steel, and in the future a computer will calculate how much feed is needed for the 7,000 pigs to be housed there. When pigs die, the amount of feed can be automatically adjusted, reducing waste and saving manpower.

Chen earned a Ph.D. in microbiology from Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat’s school of Veterinary Medicine in Munich, hoping to bring some of Europe’s breeding methods to Taiwan. At his farm in Linnei Township, he currently raises more than 13,000 pigs, a medium to large scale operation for Taiwan, and he did try to develop a brand and his own distribution channels.

Having heard the announcement to allow U.S. pork containing traces of ractopamine, Chen admitted, “from a selfish standpoint, I of course hope [American pork] is not allowed in,” before adding fatalistically: “That’s how international trade works. We can only rely on ourselves.”

Differentiation, High Value the Future

To put his operation on more solid footing, Chen not only relies on computers to raise pigs and work more efficiently but also to turn pig manure into biogas for use in power generation and harvest biogas slurry to sell to nearby farmers as fertilizer. The process epitomizes the circular economy, reducing waste and pollution to a minimum.

But getting the domestic industry to achieve a high level of professionalism remains a challenging goal, Chen said.

He recalled a visit to Denmark many years ago when he found out that local farmers who wanted to raise hogs were required to receive training in operations management and that professional academies existed to cultivate auctioning, slaughtering and carcass dressing specialists. This educational foundation has resulted in the more modern, humane and sustainable development of the industry there, as Chen acknowledged, Taiwan “is still a long way from that.”

Only when every stage of the process at the source, from breeding and rearing to slaughtering and auctioning, is upgraded can the butchering and processing steps at the back end add value to Taiwanese pork and help the industry escape the rut of having to compete on price.

“We should let consumers know what the strengths of Taiwanese pork are,” Kevin Wu said.

Wu’s Nice Garden Industrial has invested more than NT$100 million in a butchering and processing plant with the trappings of a high-tech foundry to ensure that local consumers have access to high-quality pork. The temperature and humidity is carefully controlled throughout the process to ensure the pork’s freshness, and the ceiling is transparent so that people can observe the meat handling process. The factory also seamlessly integrates cold chain and logistics, as it prepares for the possibility of exporting.

“We should think about differentiation. That’s the only way Taiwan can get better. We need to adopt and embrace international standards so that we can be competitive, whether in the domestic or export market,” Wu said.

With that in mind, the COA’s proposed NT$10 billion fund to help pig farmers will focus not only on stabilizing pork prices but also on helping slaughterhouses obtain HACCP certification and supporting the use of temperature-controlled cold chain storage facilities in the transportation and sale of pork.

By encouraging traditional market stalls to install refrigeration equipment and pig farms to add waste treatment equipment, the COA hopes to promote industrial upgrading as it opens Taiwan’s market to American pork.

“Without outside pressure, reforms wouldn’t stand a chance,” COA chief Chen Chi-chung said.

At this critical juncture in relations between Taiwan and the United States as the government opens up markets to meat products it previously considered unsafe, Taiwan’s pork industry is at the crossroads of change.

The course it chooses could determine its viability well into the future.

Have you read?

♦ Taiwan’s Secret Weapon against Pork Imports

Translated by Luke Sabatier

Uploaded by Judy Lu