Formosa Plastics: Ready to take on carbon?

Source:Pei-Yin Hsieh

The Formosa Plastics Group is the world’s 10th largest petrochemical company, but it also generates more than 50 million metric tons of carbon emissions a year. Can it really reach its goal of carbon neutrality by 2050, and how does it intend to get there?

Views

Formosa Plastics: Ready to take on carbon?

By Ching Fang WuFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 744 )

The Formosa Plastics Group is one of Taiwan’s main economic arteries. It’s four major subsidiaries – Formosa Petrochemical Corp., Formosa Plastics Corp., Nan Ya Plastics Corp., and Formosa Chemicals & Fibre Corp. – had combined revenues of NT$1.7 trillion in 2021, accounting for about 10 percent of Taiwan’s GDP.

As one of the few petrochemical conglomerates anywhere in the world to be fully vertically integrated, it provides essential support to countless industries with offerings that run the gamut from upstream refined oil products and naphtha cracking-produced raw materials to midstream plastics and downstream textile fibers.

Yet at a time of rising environmental and climate change awareness, one number stands out above any of its financial highlights: 51.83 million metric tons.

That’s the amount of carbon emissions generated by Formosa Plastics Group factories around the world in 2020. Those emissions represent 20 percent of Taiwan’s total carbon emissions, ranking second behind state-run utility Taiwan Power Co. (Taipower), a situation the group knows is untenable.

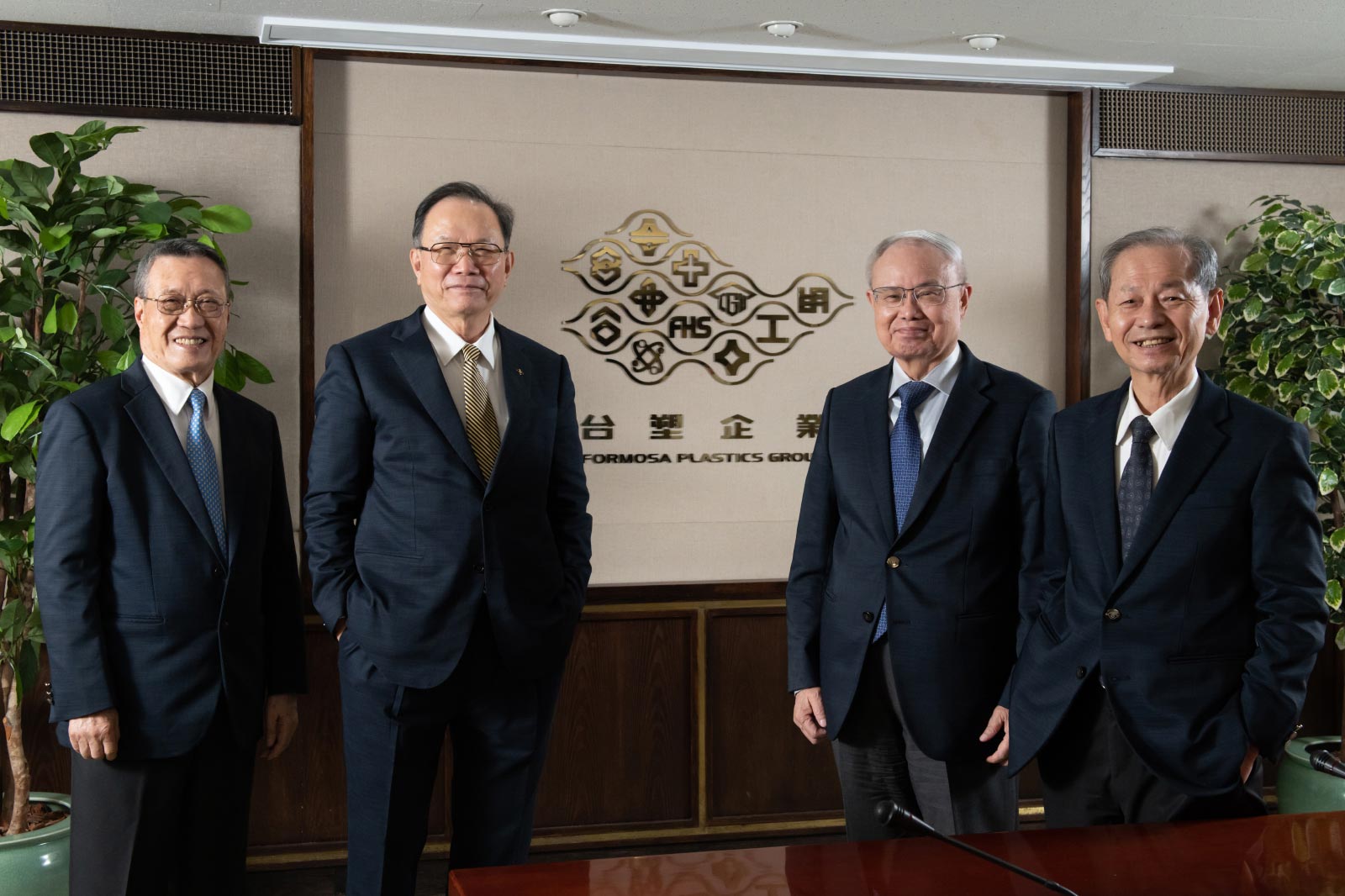

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

Feeling the heat to tackle its carbon problem, this petrochemicals Goliath has emerged as Taiwan’s first large enterprise to disclose a complete carbon reduction plan, in which it pledged to achieve carbon neutrality over the next 30 years while maintaining a growing business.

One of the world’s 10 biggest petrochemical companies with manufacturing facilities in 40 locations around the world, the Formosa Plastics Group is betting on energy transition, innovative production methods, and new business models to limit its environmental footprint.

CommonWealth magazine visited three of the conglomerate’s facilities to find out more about its actions and challenges in combating carbon emissions and climate change.

Venue No. 1: Sixth naphtha plant, Mailiao

Going from coal to gas

Formosa Plastics Group founders Wang Yung-ching (王永慶) and Wang Yung-tsai (王永在) built Asia’s biggest petrochemical facility, the Sixth Naphtha Cracker Complex, on reclaimed land off the coast of Mailiao in Yunlin County.

This petrochemical kingdom covering 2,000 hectares cost nearly NT$900 billion to build and includes an industrial port, a coal-fired power plant and more than 50 factories that handle everything from plastics production to upstream refining.

This vertically integrated hub, which allows the group to maintain complete control over the supply chain and its flow of raw materials, is powered by a hidden energy artery.

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

When coal ships arrive at the industrial port in Mailiao, their coal is unloaded onto an enclosed conveyor belt system and transported to the complex’s coal bunker. It then is sent in one of two directions – either to the coal-fired plant to generate power for sale to Taipower or to co-generation plants to generate the electricity and steam used by factories in the complex.

The first step in the carbon neutral campaign will be to overhaul this major coal artery.

By 2028, the most common ships entering the industrial port may be LNG carriers rather than bulk coal ships.

The Mailiao power plant used to supply electricity to Taipower has three coal-fired generators totaling 1800MW in installed capacity, but they will be taken out of service by 2025. Two 1200MW gas-fired generators will then be built on the same site to replace the coal units at a cost of NT$95.2 billion, a sum roughly equal to Formosa Petrochemical’s paid-in capital.

The transition to natural gas will cut the conglomerate’s generation of carbon emissions by more than 6 million metric tons in the next 10 years, accounting for more than half of its 2030 carbon reduction goal.

But Formosa Petrochemical Chairman Chen Bao-lang (陳寶郎) bluntly acknowledged that natural gas was still a carbon-generating fossil fuel that can only serve as a transitional energy, and that using it would have economic consequences.

“If Taipower does not adjust its electricity purchase price, we will definitely be selling (gas-fired electricity) to Taipower at a loss, because natural gas is really expensive right now,” he said. “Taiwan has the fourth lowest electricity prices in the world. We have to think about more rational pricing.”

On the cogeneration side, Chen said the company was considering using zero-emissions biofuels, such as coconut and palm shells from Southeast Asia or wood pellets from North America.

“CPC Corp. Taiwan and Formosa Plastics could both develop hydrogen energy, but only Formosa Plastics’ process will be fully integrated, from importing natural gas and producing hydrogen to generating power,” said Taiwan Research Institute Vice President Lee Chien-ming (李堅明).

Building a foundation for natural gas infrastructure, Lee said, will pave the way for the group’s hydrogen development.

Venue No. 2: Renwu Plant, Kaohsiung

Testing ways to capture CO2

In Formosa Plastics’ early days, it produced industrial alkalis, generating excess chlorine. To recycle that chlorine, Wang Yung-ching decided to make plastics, and he applied for a loan backed by American economic assistance to build Taiwan’s first PVC (polyvinyl chloride) factory in Kaohsiung.

Some 60 years have gone by since then, and the Formosa Plastics Group now produces more than 3 million metric tons of PVC a year, making it a major global supplier of the material. Now, the material Formosa Plastics needs to recycle is no longer chlorine, but colorless and odorless carbon dioxide.

To address the issue, Formosa Plastics’ factory in the Renwu area in Kaohsiung completed a pilot carbon capture pilot plant in January 2022 in partnership with the Industrial Technology Research Institute and National Cheng Kung University. The project will collect more than 30 metric tons of carbon dioxide a year from the test project’s chimney and purify it.

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

Why is this happening at the Renwu factory?

“Because in Renwu, we have a chlorine alkali plant, and we have hydrogen,” said Formosa Plastics Chairman Jason Lin (林健男).

After carbon dioxide is captured, it has many applications. For example, it can be turned into alkanes – the most basic of petrochemical raw materials such as methane and ethane – through the process of hydrogenation, and then processed further into plastics, clothing, and other petrochemical products.

Formosa Petrochemicals is also testing carbon capture at the Mailiao complex and intends to use the latest solutions developed by Lummus Technology, the American company that originally designed the naphtha cracking process used in Mailiao

While Formosa Plastics and Formosa Petrochemical are both testing capturing carbon directly from factory chimneys, Nan Ya Plastics’ ethylene glycol plant is giving some of the carbon generated by its production processes to downstream suppliers such as the Chang Chun Group to make acetic acid.

It is also planning to convert carbon dioxide into semiconductor and industrial grade raw materials, and hopes to be able to recycle all the carbon dioxide it generates into usable resources by 2025.

Venue No. 3: Nan Ya Plastics, Shulin

Devising a new business model with Adidas

Nan Ya, the world’s largest plastics processor, has been developing green materials for years because of the pressure imposed by its major international clients to embrace sustainability and carbon reduction.

“Behind the competition between brands is competition between supply chains on carbon reduction,” said Sunny Huang (黃冠華), executive director of garment manufacturing giant New Wide Group, who expected brand pressure on carbon reduction to be ramped up this year.

One key Nan Ya initiative is to recycle PET bottles.

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

Nan Ya Chairman Wu Chia-chau (吳嘉昭) said the company’s recycled PET technology is mature, and 90 percent of it is used to produce long-fiber functional textiles that have relatively high technical thresholds. Nan Ya recycled nearly 10 billion PET bottles last year, resulting in an 84 percent reduction in carbon emissions.

The next step in the company’s circular economy campaign is helping big brand clients adjust their designs and materials and establish a recycling business model.

Nan Ya, for example, collects waste materials from contractors used by its international clients and then sorts them mechanically at its Shulin factory. To eliminate the sorting process and make materials easier to recycle, the company is working with clients such as Adidas to design and develop different clothing accessories such as buttons and zippers using a single material.

The latest frontier: sustainable diapers

Nan Ya is not the only group subsidiary collaborating closely with customers on sustainability. Formosa Plastics and Formosa Chemicals & Fibre are helping clients explore ways to create added value through the carbon cycle.

Beyond its support for the big international brands, Formosa Plastics has gotten involved in such niche projects as diapers and fishing nets.

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

Traditional diapers use several different materials, including polyethylene for the outer waterproof layer, polypropylene (PP) for the inner non-woven fabric, and a superabsorbent polymer (SAP) liquid-absorbing material for the diaper’s middle layer. The first two are standard materials, but Formosa Plastics is the only producer of SAP in Taiwan.

Because of this complexity of materials, recycling diapers is generally considered an impossible task.

Formosa Plastics is giving it a shot, nonetheless, by teaming up a diaper maker and a recycler. It has developed a PP that will be used to produce both the inner and outer layers of diapers, and then Yi Chun Green Technology Co., a recycling startup, will collect these specially designed diapers when they are discarded, treat them with enzymes, and process them into recycled materials.

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

Disposable diapers that have typically been incinerated may soon be turned into fibers, agricultural water-retaining crystals, and even water-absorbent materials covering submarine cables.

Formosa Plastics’ sustainable diaper project could enter its next phase in Taoyuan in the first half of this year, with expectations of recycling about 4,000 diapers and saving half a metric ton of carbon emissions per month.

Meanwhile, Formosa Chemicals & Fibre, Taiwan’s biggest nylon fiber manufacturer, has chosen marine waste as its sustainability battlefield.

The company has worked with outdoor sporting goods chain Patagonia Taiwan since 2019 to convert marine waste into recycled nylon through a chemical process. It currently produces about 500 metric tons of recycled nylon per month, and announced in January it would invest NT$1 billion to increase its capacity three-fold.

Building on that partnership, Formosa Chemicals & Fibre is also collaborating with King Chou Marine Technology Co., the world’s second largest manufacturer of fishing gear.

King Chou collects and disentangles discarded fishing nets and sends them to Formosa Chemicals & Fibre, which then uses them to make recycled caprolactam, a key element in the manufacture of synthetic fibers such as Nylon 6. It sells for US$2,600 per metric ton, 30 percent more than the original fishing net material was worth.

Still a ways to go

These three major initiatives – going from coal to gas, capturing carbon, and recycling materials – are all important but will still only cut the Formosa Plastics Group’s carbon emissions by just over 10 million metric tons over the next 10 years.

In the 20 years from 2030 to 2050, the Formosa Plastics Group will still have to deal with its remaining 40 million tons a year of carbon emissions. It plans to do so through the development of carbon-free hydrogen, ammonia, and biomass energy and mature carbon capture, carbon sequestration, and carbon utilization technologies.

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

(Source: Pei-Yin Hsieh)

After the second oil crisis in the late 1970s, the petrochemical industry was branded internationally as a sunset industry, and many small and medium-sized downstream vendors went bust.

At the time, CommonWealth interviewed Wang Yung-ching about the petrochemical sector’s potentially bleak future, and his assessment is as applicable today as it was then.

“Saying that the petrochemical industry does not have a future is wrong. The future is created by people. The Formosa Plastics Group is bound to find a new way.”

Have you read?

♦ Moving towards a world without oil, how can Taiwan’s petrochemical industry adapt?

♦ Chang Chun turns CO2 into chemicals

Translated by Luke Sabatier

Uploaded by Penny Chiang