Guest-Writer's Submission

History of Malay Singaporeans in 10 Objects - Part 1

Source:Widya Zulkassim-Barnwell

Singapore has always been part of a Malay world. To approach the history of the Malays in Singapore, we need to look deeper and longer. And so, we begin, 700 years ago.

Views

History of Malay Singaporeans in 10 Objects - Part 1

By Faris Joraimiweb only

History and Colonialism

Ethnic Chinese make up a large majority in Singapore, but a quarter of the population is composed of Malays, making them the country’s biggest ethnic minority. They may seem out-of-place in popular images of Singapore, which is often imagined in global media as a glitzy East Asian financial centre, a Hong Kong or Shanghai transplanted to Southeast Asia.

However, Singapore has always been part of a Malay world. The Malay Archipelago - extending from the northernmost tip of Sumatra eastwards all the way to the island of Sulawesi - encompasses the modern nation-states of Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei and southern Thailand. Although incredibly diverse, these different lands share several elements that allow us to consider them as being part of a similar ‘realm.’

For one, the Malay Archipelago shares a common language. From the 15th century onwards, the Malay language became the language of trade and diplomacy that bridged all the major economic powers in the region. It was the region’s lingua franca. Francois Valentijn, a 16th-century Dutch naturalist, compared Malay to the role played by French and Latin in Europe. It is no wonder that the Indonesian nationalists adopted Malay as their unifying language in 1928, whence it became known as Bahasa Indonesia.

While there are differences between Bahasa Indonesia and Bahasa Melayu, the two languages are rather mutually intelligible. Both belong to one branch of the Austronesian language family; the other nine are in Taiwan. Interestingly, these languages still share similar words to this day, suggesting the widespread reach of Austronesian peoples:

|

Language |

One |

Two |

Three |

Four |

Five |

Eyes |

Fire |

Pig |

|

Malay |

Satu |

Dua |

Tiga |

Empat |

Lima |

Mata |

Api |

Babi |

|

Javanese |

Siji |

Loro |

Telu |

Papat |

Limo |

Mata |

Api |

Babi |

|

Tagalog |

Isa |

Dalawa |

Tatlo |

Apat |

Lima |

Mata |

Apoy |

Baboy |

|

Siraya |

Sasaat |

Duha |

Turu |

Tapat |

Tu-rima |

Mata |

Apuy |

Vavoy |

|

Paiwan |

Ita |

Drusa |

Tjelu |

Sepatj |

Lima |

Matsa |

Sapuy |

Vavuy |

|

Puyuma |

Isa |

Zuwa |

Telu |

Pat |

Lima |

Mata |

Apuy |

Vavuy |

|

Amis |

Cecay |

Tosa |

Tolo |

Sepat |

Lima |

Mata |

Namar |

Fafoy |

Blue: Malayo-Polynesian languages

Red: Formosan languages

The different cultures of the region are also bound by similar belief systems going back to their ancient Austronesian roots. They also enjoy a shared literature: Panji and Seri Rama are characters popular amongst inhabitants living in the area stretching from the Malay Peninsula to Bali.

In the heart of this world lies Singapore. When Stamford Raffles of the British East India Company decided to establish a settlement here in 1819, there were hundreds of Malay households and several Chinese families. The island was part of the Johor-Riau Sultanate, a Malay kingdom which was then in decline.

Raffles exploited a succession crisis in the kingdom to make it look like he had the permission of the Sultan and his officials to found his settlement. In 1824, the British and the Dutch East India Companies signed an agreement that partitioned the Malay World along the Straits of Malacca and Singapore. This agreement put Singapore under British jurisdiction. From 1824 onward, the British stripped the Sultan and his officials of their authority st in Singapore, and gained full control of the island.

The Chinese, Indians, and Arabs had been present in the Malay world for centuries. However, British and Dutch colonization of the Malay world transformed the demographic composition, as well as, the relationships amongst the different ethnic groups in many places in the Malay world.

In Singapore, Chinese migrant labourers flooded the British colony in large numbers. By the mid-19th century, the Malays had become a minority group. The minority status of the Malays continues to impact the structural disadvantages they face until today.

Negative stereotypes about the Malays in Singapore are well and alive. There is a failure in understanding how the colonization of the Malay world has left behind legacies that have shaped the experiences and outlook of the Malays in the country.

Even amongst the Malays, the trend toward increasing Islamic conservatism encourages many to ignore or overlook key aspects of their history and identity that are not associated with being “Muslim.” To approach the history of the Malays in Singapore, we need to look deeper and longer. And so, we begin, 700 years ago, with our first object.

1. The Kala Armlet

Photo courtesy of National Heritage Board

Photo courtesy of National Heritage Board

In 1926, an excavation at Bukit Larangan (known today as “Fort Canning Hill”) unearthed several crucial finds, among which was a golden armlet which dated back to the 14th century, around the time when the fabled Kingdom of Singapura flourished on the island. An account of Singapore’s Malays will not be complete without reference to its pre-colonial history, when Singapore was inextricably linked to the culture of the Malay world. This is reflected in the armlet’s visual aesthetic.

Its most striking feature is the “Kala” motif: the face of a mythical creature that finds expression in many ancient structures throughout Southeast Asia. Farish Noor, a historian of Southeast Asia, recounts the mythological background of the Kala motif:

“In Hindu mythology, Kala was a disobedient being who had been ordered by Siva to eat himself as a punishment. Fortunately, Siva relented halfway and Kala was established in the pantheon as a guardian figure. His likeness – a truncated head with protuberant eyes, leonine nose, gaping jaws often spewing luxuriant foliage, and occasionally two arms – can be found guarding the entrances of most early temples in Cambodia and Thailand.”

Left: Kala on an archway in Borobudur, Central Java (Courtesy of Troppenmusuem)

Right: Kala at the Keraton or Palace in Yogyakarta (Courtesy of Herman Lim)

This armlet is consistent with Malay writings that attest to the existence of a flourishing kingdom that existed around the 14th century in Singapore. It is also an important reminder of the Malays’ religious history: prior to conversion to Islam from the 15th century onwards, Malays were Buddhists and Hindus. Symbols from these belief systems were incorporated into their art.

Have you read?

♦ What the Movie Gets Right and Wrong about the 'Rich Asians'

♦ Singaporean Memories: Playground History Reflects Local Life

♦ Singapore After Lee Kuan Yew

2. Diorama: Signing of Singapore Treaty, 1819

Photo courtesy of National Library Board, Singapore

This diorama at an exhibition depicts the signing of the treaty in 1819 which led to the establishment of a British trading settlement in Singapore. The figures are, from right to left, William Farquhar, the Temenggung Abdul Rahman, Sir Stamford Raffles, Tengku Hussein and finally, his son Tengku Ali.

Farquhar and Raffles were representatives of the British East India Company. Abdul Rahman was the Temenggung of the Johor-Riau Sultanate. A ‘temenggung’ was an important official in a Malay kingdom, in charge of maintaining internal security as well as policing the waters around the ports by fending off pirates and collecting tolls.

Tengku Hussein was the eldest son of the recently deceased Sultan. The court of Johor-Riau had made Tengku Hussein’s brother sultan instead of him. Knowing about his bid for the throne, Raffles promised to make him Sultan of Singapore and Johor if he agreed to sign a treaty granting him permission to set up a trading post. Tengku Hussein agreed. He was worried that Raffles would kidnap him and banish him to India if he refused.

Further, Raffles’ invasion and sacking of several important port-kingdoms in the region had created a climate of fear amongst the native elites. Tengku Hussein signed the treaty fully aware of the potential threat of force that could be used against him.

The 1819 treaty only allowed the British authority over the area around the Singapore river basin. The rest of the island was still administered by the Temenggung, with the Sultan as its titular head.

This changed in 1824 when the British imposed another treaty that forced the Sultan and Temenggung to cede all authority over Singapore to them.

By 1824, the Dutch and British agreed to divide the Malay Archipelago between them, with the British taking the Malay Peninsula and Singapore, while the Dutch had Sumatra and all the islands south and east of the Singapore Straits under their sphere of influence.

With the Dutch no longer a threat, the British did not need Sultan Hussein as an ally to legitimize their claim over Singapore. The British withheld monthly payments the Sultan was entitled to under the 1819 treaty. The new agreement – named the Treaty of Friendship and Alliance – gave a final sum of payment to both the Sultan and Temenggung; in return, Singapore and its surrounding islands were fully ceded to the British.

The signing of the Singapore Treaty on 6 February 1819 is presented in official histories as the defining moment marking Singapore’s road to nationhood. Until recently, school textbooks gave short shrift to Singapore’s pre-colonial history and mark the beginning of Singapore history with Raffles in 1819.

Generations of Singaporeans grow up without learning how Singapore already belonged to a native state. Many remain unaware that the founding of the British takeover of Singapore was the result of the dispossession of indigenous peoples by such seemingly ‘legal’ means, that were violent and coercive no less.

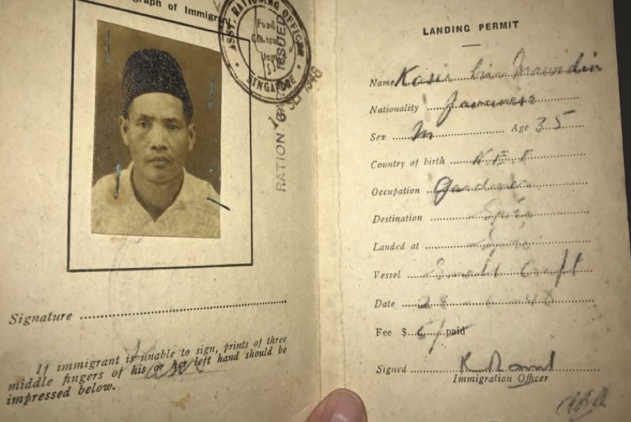

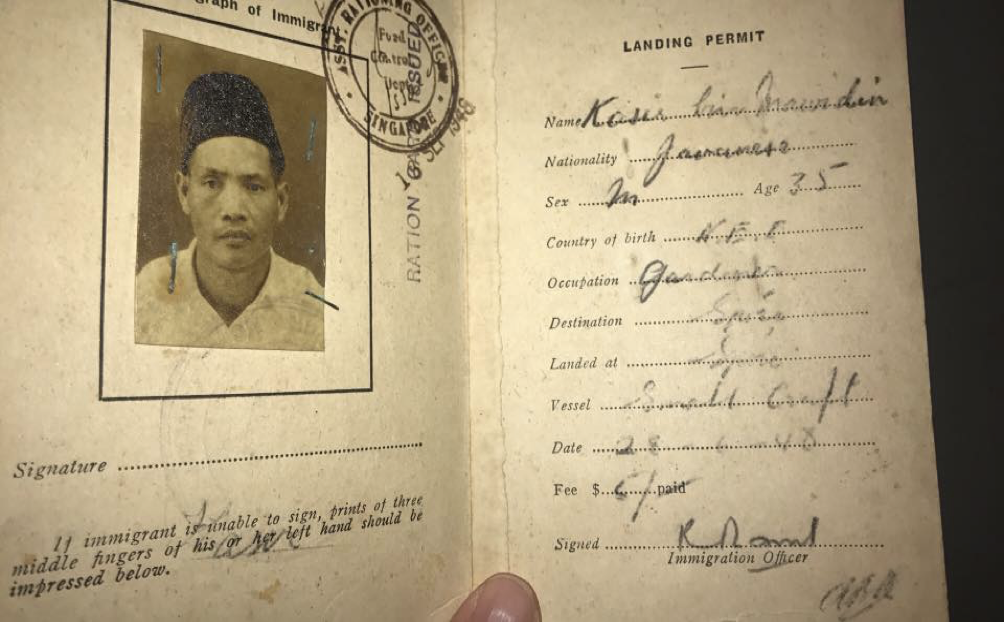

3. Landing Permit

Photo courtesy of Widya Zulkassim-Barnwell

Photo courtesy of Widya Zulkassim-Barnwell

This landing permit belongs to an ‘anak dagang’ from Java, which was then under Dutch rule. It encapsulates the highly mobile and semi-nomadic nature of people in the Malay Archipelago. This landing permit reminds us that Malay Singaporeans are members of the Austronesian peoples, who have a widespread distribution from Madagascar eastwards to the farthest reaches of Polynesia.

Many of these societies are notable for being maritime cultures with great seafaring traditions, and those inhabiting the lowland coastal and riverine areas in the Malay Archipelago are no exception.

‘Dagang’ in Malay now translates to English as ‘commerce’ or ‘trade.’ ‘Anak dagang’ means, therefore, a ‘trader.’ However, ‘anak dagang’ in Malay originally referred to those who wandered away from home to seek a livelihood. This man’s journey to Singapore in 1948 was part of that long tradition. To voyage from one’s home island (‘pindah pulau’) to travel elsewhere (‘merantau’) is an important rite-of-passage in many communities of the region, such as the Minang, a matrilineal community primarily concentrated in the historically and culturally interlinked regions of Minangkabau in Sumatra as well as Negri Sembilan in Malaysia.

Minang men are compelled to leave their villages to fend for themselves once they reach a certain age. The Javanese too established a widely distributed diaspora across the Archipelago, as have the Baweanese, and Bugis. All these cultural identities now make up the ‘Malay’ community in Singapore. So ingrained is this practice that it has been immortalised in poems and songs.

This landing permit, issued by the British colonial government, is a statement on the effects of European partition of the Malay world. The cultural practice and meaning of travel and settlement, and consequently, the status and identity of groups native to the Malay world, were transformed. The borders established and policed by the colonial powers made Singapore and parts of the Malay world ‘foreign’ to one another. The borders of the British and Dutch colonial states made some groups native to the Malay world ‘immigrants’ in Singapore, whereas Singapore had always been part of a shared cultural world where people moved freely.

In the next part of this series, we will examine how Malays opened new frontiers in modern Singapore, infusing the city with a dynamic intellectual life and pioneering its golden age of popular culture.

Next >> History of Malay Singaporeans in 10 Objects - Part 2

Written by Faris Joraimi

Edited by Sharon Tseng