Guest-Writer's Submission

History of Malay Singaporeans in 10 Objects - Part 3

Source:Family portrait of Yusof Ishak, First President of The Republic of Singapore

The Singaporean Malay experience is characterised by moments of triumph and struggle. Today, they continue to confront issues like socio-economic disadvantage and racial discrimination.

Views

History of Malay Singaporeans in 10 Objects - Part 3

By Faris Joraimiweb only

(This article is the third part of the three-part series: History of Malay Singaporeans in 10 Objects)

On the Margins in Independent Singapore

In this final instalment of A History of Malay Singaporeans, we discuss the status of Malays in independent Singaporean society. Living in a Chinese-majority city cut off from the Malay Peninsula and its surrounding islands, they eventually began to feel the effects of their disadvantaged position. Anthropologist Tania Li argued that in the early years after independence, average Malay household income was in fact higher than that of the Chinese. They were well employed as civil servants and members of the uniformed services. Recruitment of Malays into both professions significantly declined thereafter.

Today, Malays remain the most economically disadvantaged community in the country, and they remain commonly stereotyped as ‘lazy.’ The Malay language’s role as Singapore’s lingua franca was also replaced by English. Despite official rhetoric that continues to characterise Singapore as a multi-racial nation, by the 1990s, Lee Kuan Yew had already begun to openly call Singapore a “Chinese society,” as if its other communities did not exist.

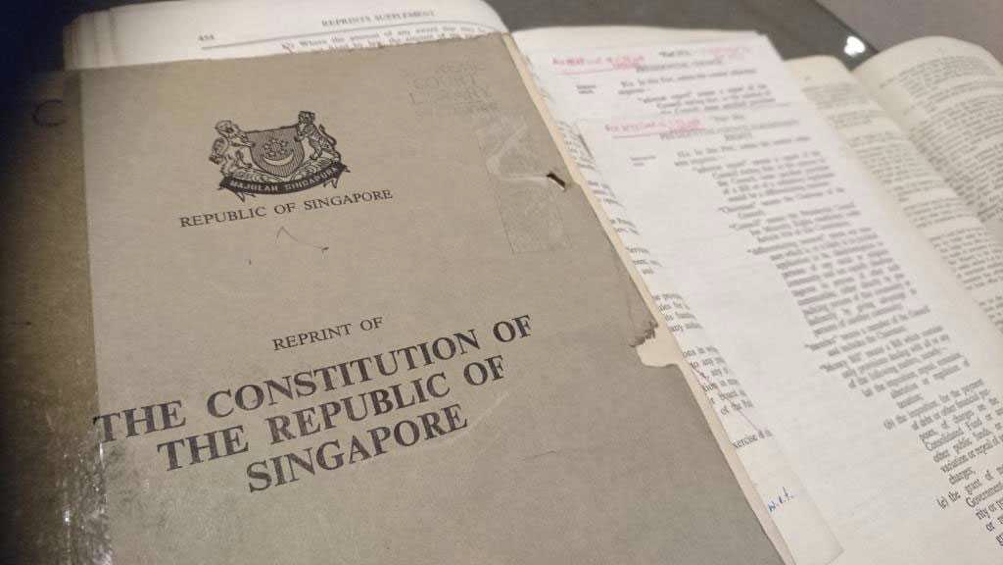

8. The Singapore Constitution

Photo courtesy of The Supreme Court of Singapore

Photo courtesy of The Supreme Court of Singapore

The Constitution of the Republic of Singapore came into force on 9 August 1965, the day Singapore was expelled from the Federation of Malaysia. It is derived from elements of the Constitution of Malaysia as well as the Constitution of the State of Singapore (introduced when Singapore became a member of the Federation).

The Constitution is a legally binding document but there is always plenty of room for interpretation. One section of the Constitution is particularly significant to Malay Singaporeans: Article 152.

‘Minorities and special position of Malays'

(1) It shall be the responsibility of the Government constantly to care for the interests of the racial and religious minorities in Singapore.

(2) The Government shall exercise its functions in such manner as to recognise the special position of the Malays, who are the indigenous people of Singapore, and accordingly it shall be the responsibility of the Government to protect, safeguard, support, foster and promote their political, educational, religious, economic, social and cultural interests and the Malay language.’

Article 152 has provoked debates that have not been resolved. How does Singapore reconcile its constitutional recognition of Malays as an ‘indigenous’ community with a ‘special position,’ with its national postulate of multiracial equality?

Scholars have studied how the Singapore state applies different approaches to engaging with Article 152. Scholar Lily Zubaidah Rahim, in her book The Singapore Dilemma: The Political and Educational Marginality of the Malay Community writes that the Singapore government has applied a minimalist, as opposed to an interventionist approach. The government used to (but no longer) provide free tertiary education for Malays.

Compared to the government’s aggressive promotion and establishment of ‘Special Assistance Plan’ (SAP) schools dedicated to the teaching of the Chinese language, culture and history and where almost all students are Chinese, this is a relatively ‘minimalist’ method of affirmative action. These SAP schools were originally Chinese-medium schools that were converted into ‘special schools’ to help ‘preserve’ Chinese language and culture after English was adopted as the main language of instruction in Singapore schools from the beginning of the 1980s onward. There were also Malay-medium schools but despite Article 152, these schools were not given the same resources and status as SAP schools. In fact, all Malay-medium schools have been shut down.

Playwright and writer, Alfian Saat, argues that specific policies and actions pursued by the government fail to live up to the spirit of Article 152. These include the seizure of the Istana Kampung Gelam, the former residence of descendants of Sultan Hussein in 2000, the ban against the wearing of headscarves by Malay/Muslim female students in public schools two years later as well as the inadequate funding allotted to Islamic schools. None of these live up to “foster[ing] and promot[ing]” the “educational, religious […] and cultural interests” of the Malay community.

9. Mark III Rifle

Photo courtesy of Hafiz Rashid, Malay Heritage Centre

Photo courtesy of Hafiz Rashid, Malay Heritage Centre

This corroded rifle was used during the Second World War by a soldier of the Malay Regiment. Although rusty and worn, it is a poignant reminder of Malays’ contributions to the island’s defence during the Battle of Singapore.

The heroic last stand of the Malay Regiment at Pasir Panjang is particularly familiar to most Singaporeans, where Lieutenant Adnan and his plucky band of Malay soldiers were outnumbered by the Japanese thirteen to one, yet mounted a formidable resistance. Despite our formal recognition of Malay heroism and military sacrifice in war, the reality paints a different picture.

The Singapore Armed Forces’ manpower policies are still deeply controversial: Malay servicemen are still barred from particular vocations, while at the same time, Malays are disproportionately assigned to the police force and civil defence. Former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew once openly said that it is “tricky business” putting a Malay officer who is “very religious” and “has family ties in Malaysia” in charge of a machine gun unit. These notions open up questions about how an ethnic minority group has to pay the price for the majority’s perceptions of danger, arising from the siege mentality of being a Chinese-majority population ‘surrounded’ by Malay-speaking, Muslim-majority countries. No such suspicions are harboured against the Chinese, many of whom have “family ties in Malaysia” as well.

In Singapore, good citizenship is strongly associated with participation in the military, as seen in how membership in it is a ‘national’ duty. Such policies therefore diminish the Malays’ ‘Singaporeanness’ compared to the other ethnic groups.

The corroded rifle symbolically reflects a bygone period when Malays used to make up a significant proportion of the armed services, until recruitment of Malays was halted in 1967. This is frequently seen as an affront to their position as the country’s indigenous people.

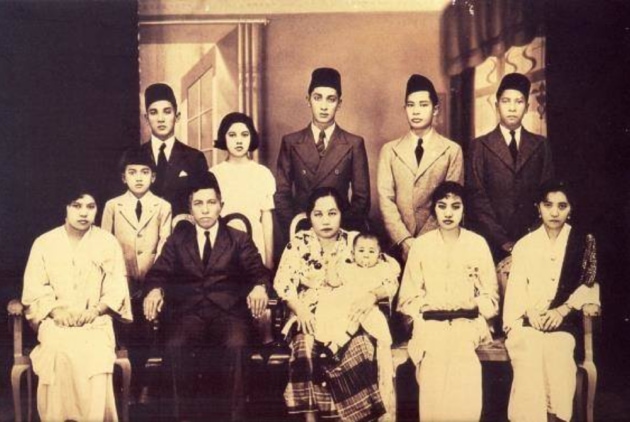

10. Family Studio Portraits

Family portrait of Yusof Ishak, First President of The Republic of Singapore (last row, middle)

Family portrait of Yusof Ishak, First President of The Republic of Singapore (last row, middle)

Family portraits shot in a studio are a common feature of Malay households. Usually found framed on a wall where it will likely be visible to guests, such as in the living room, they are a deliberate exercise in displaying an idealised image of the family to the outside world. This is done through the inclusion of specific status symbols, such as a son or daughter in graduation robes — signalling the importance placed on academic achievement, which occasioned the moment to be captured.

Graduation robes – as in many contemporary examples – also signal the family’s social mobility, as the succeeding generation secures its chances for a successful career and guarantees the continuation of the family’s comfortable socio-economic position. Western business attire is also a popular choice amongst Malay families taking studio portraits, as it carries connotations of success in one’s career, and more significantly, helps project a modern, progressive character. The distinction between Western fashion with its ‘modern’ associations and Malay garments which suggest rootedness to tradition is interesting to note when observing these portraits.

In the family portrait of Yusof Ishak, independent Singapore’s first President, we see the typical condition of urban, middle-class Malays with reasonable wealth and social standing. All except one of the women are wearing kebaya panjang, a loose tunic popular amongst women throughout the Malay Archipelago until the late 20th century.

All the men are decked in suits and ties, but also the songkok: a black velvet cap popular amongst urban Malays of the region. In Indonesia, the cap – known as peci - was politically symbolic, and it was famously worn by nationalists like Sukarno. This headdress was adapted from the Ottoman tarboosh. One of the girls is in a European blouse. Images like these best capture Malay cosmopolitanism.

By and large, however, there is a tendency to portray women as bearers of tradition, whereas the men in their business suits reflect traditional roles which saw public life and going to work as predominantly ‘male’ endeavours. On festive occasions, the entire family is usually photographed in Malay garb. In these cases, multiple generations are unified through adherence to a shared set of cultural values.

Family portraits are an interesting window into the way Malay families perceive themselves. Self-representation involves conscious decisions, and these involve notions of class, tradition and social values.

Conclusion

The Singaporean Malay experience is characterised by moments of triumph and struggle. Today, they continue to confront issues like socio-economic disadvantage and racial discrimination. But from family portraits displaying social mobility to a 19th-century book urging social change, one finds in the Malays, too, aspirations to exist with dignity. Younger Malays, through resilience and talent are successfully resisting outdated stereotypes.

It is never easy to capture the history of a people in a single sitting. However, this undertaking aims to provide a nuanced and meaningful introduction to the complex issues Singaporean Malays face. More importantly, it hopes to inspire greater understanding of how truly diverse and multifaceted Singapore’s history is.

Written by Faris Joraimi

Edited by Sharon Tseng