Speak Plainly, Mr. Chairman Xi

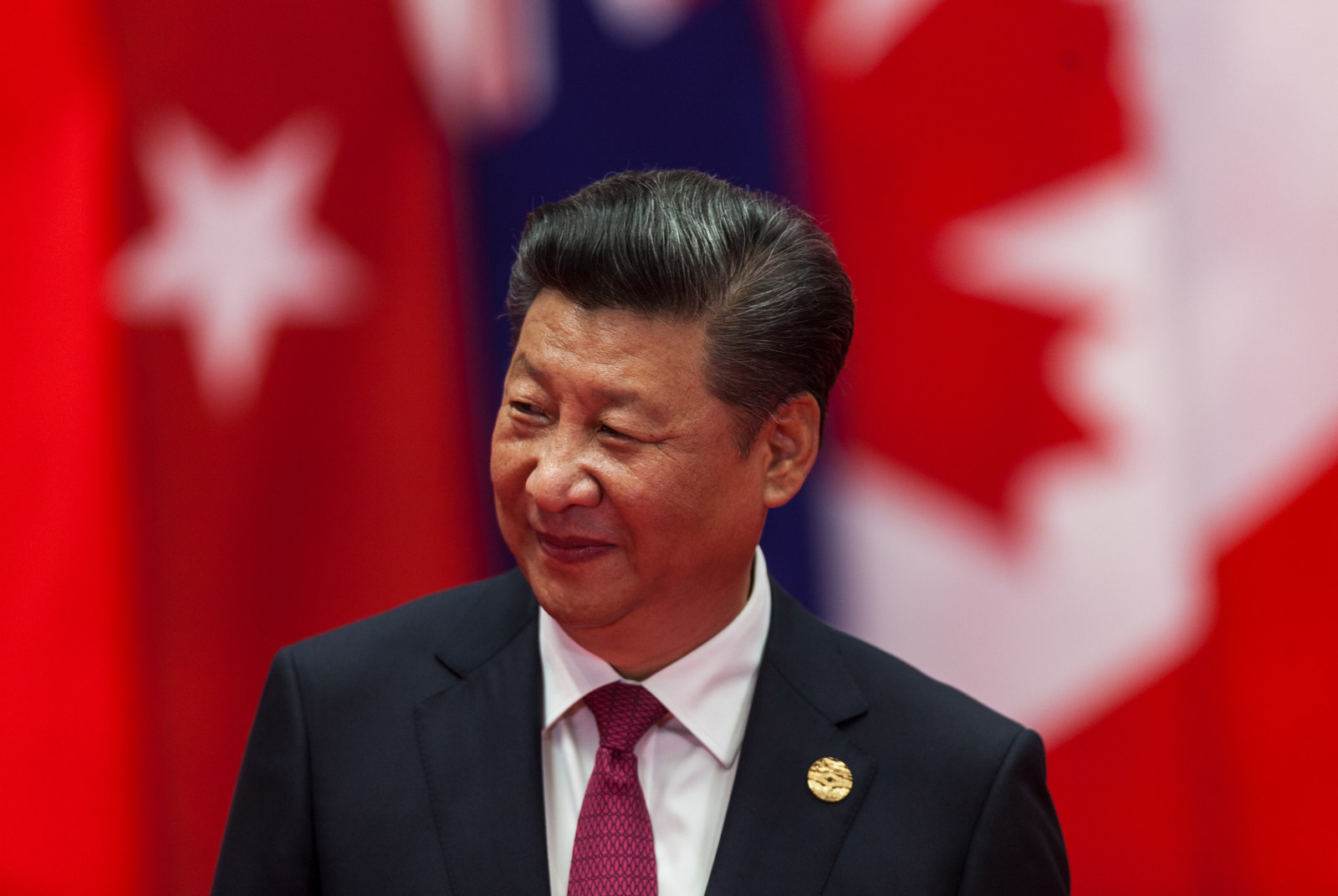

Source:shutterstock

China's rhetoric on global peace raises concerns about its intentions and ability to address conflicts effectively. The opaque and self-glorifying language of the Chinese Communist Party's discourse complicates international understanding and invites misinterpretation. As China seeks greater global influence, questions arise about the clarity of its intentions. An opinion piece by David Bandurski.

Views

Speak Plainly, Mr. Chairman Xi

By David Bandurskiweb only

In recent months, it has been clear that China envisions itself taking a much greater role in maintaining world peace. In February, its foreign ministry released a concept paper claiming that it would “eliminate the root causes of international conflicts” through Xi Jinping’s so-called Global Security Initiative, guiding humanity toward “the lofty cause of world peace and development.” Within days, China’s government released a position paper on the settlement of what it continued to insist on calling the “Ukraine crisis.”

The callousness of this simple replacement of language must not be shrugged off. As the war in Ukraine grinds through its 15th month, innocent civilians in this sovereign state are dying every day in Russian drone and missile strikes. Can peacemaking really be entrusted to a power that cannot even speak the word “war”?

China claims it has played a neutral role since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and is therefore in a unique position to play peacekeeper. The substance of its official discourse tells a markedly different story. Even as it talks about peace for the world, the Chinese Communist Party remains fixated on its own political power, and that of its general secretary, in ways that suggest a level of detachment from global reality. To make matters worse, it seems chronically incapable of parting ways, even as it conducts diplomacy, with the turgid Maospeak that is a legacy of its political culture as a Leninist political party.

Xi Jinping’s call last month with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, hailed by China as an expression of its goodwill, was a prime case in point — insofar as we can judge the call from the wave of official coverage that followed. Published in the CCP’s People’s Daily the day after the call, the read-out begins with Xi Jinping thanking the Ukrainian side “for its strong support for the evacuation last year of Chinese citizens.” The omissions immediately loom large. There is no mention of Russia’s invasion, or Russia at all. Naturally, there is no talk of “war.” Why was it necessary to evacuate Chinese citizens from Ukraine last year?

Next comes the obligatory empty talk — which must have brought a chortle from Zelensky — about “mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity” as the “political foundation of China-Ukraine relations.” But it is in the next line, as the read-out begins to outline China’s call for peace talks, that we descend straight down into remorseless CCP-speak. “We have successively proposed the ‘Four Shoulds,’ the ‘Four Togethers’ and the ‘Three Points for Consideration,’” it reads.

This game of speaking in code is part of the instrumental language of China’s Leninist ruling party. For generations, CCP leaders have been steeped in this specialized discourse, which serves to construct power, conceal as it declares, and obliterate. In the Xi era, the discursive confections of the CCP have grown more elaborate than at any point in the reform era, even as controls on speech have intensified. Formulations like the “Four Shoulds” and “Four Togethers” are impossible for China’s leaders to resist. Like boxes filled with imaginary things, they can be packed and unpacked, stacked and unstacked.

Last year, a different “Four Togethers” was promoted as Xi Jinping’s answer to online governance — accompanied by “Four Principles” and “Five Propositions.” But never mind. The boxes can always be emptied and refilled with our political imaginations. Such language, as George Orwell wrote in an essay on the subject, “is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.”

The “Four Shoulds,” the foundation of China’s peace proposal, was introduced by former foreign minister, Wang Yi (王毅) in March last year, within two weeks of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The concept’s foolishness shone brightly against the bleak backdrop of Mariupol, where mass graves were being dug for the Ukrainians killed under intense Russian bombardment: The sovereignty and territorial integrity of nations should be respected; the purposes and principles of the UN Charter should be respected; all countries’ legitimate security concerns should be taken into account; and every effort beneficial to the peaceful resolution of the crisis should be supported.

Meanwhile, as Xi Jinping dialogued closely with Putin, the People’s Daily and other state media parroted Russian narratives about US and NATO culpability for the war, and spent weeks on end blatantly spreading Russian disinformation about alleged US biological weapons facilities in Ukraine. These untruths were amplified over the effective obliteration of Ukraine as a sovereign state in China’s media space, most egregiously symbolized by the total absence of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky from the pages of the People’s Daily. In fact, from the outbreak of the war in Ukraine in February 2022 to Xi Jinping’s phone call with Zelensky last month, the president was mentioned just twice in the CCP’s flagship newspaper — in separate tributes for Xi Jinping’s reappointment in October 2022 as the Party’s general secretary, and in March as president.

Let the absurdity of that fact sink in for a moment.

The People’s Daily is meant to coalesce and communicate the power and vision of the CCP leadership under Xi Jinping, to signal its position on domestic and foreign affairs. It is the authoritative reference book to which observers everywhere turn for a glimpse of what China’s authoritarian strongman and his acolytes, who govern a population of 1.3 billion, are thinking. And yet, for nine months last year, as missiles rained down on millions of innocent Ukrainians, their president merited not a single mention because this violence was being unleashed by China’s staunchest ally, Russia’s Vladimir Putin. Over the succeeding four months, Zelensky merited mention just twice — not because his nation was at war, but because he had congratulated Xi Jinping on his political successes.

The base logic of political power is inescapable in China’s language of diplomacy. In a keynote address at a Beijing summit of world political parties on March 15, Xi Jinping announced the formation of the Global Civilization Initiative (全球文明倡议). He claimed that the CCP had advanced “the progress of human civilization” by creating “Chinese-style modernization as a new form of human civilization.” In turn, this would contribute to a process of global civilizational exchange that would “make the garden of world civilizations more abundant,” and lead us all to what Xi calls “a community of common destiny for humankind.”

What happens when we pick apart one piece of circuitry in this elaborate verbal machinery? In his political report to the 20th National Congress last year, Xi Jinping elaborated on the promise of “Chinese-style modernization,” and made clear that its most fundamental precondition is “adhering to the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party.” So there we have it, lurking just behind another fanciful turn of phrase: the raw assertion of power and legitimacy.

It should not at all surprise us, then, to find that the Chinese read-out of the Zelensky call last month once again exploited the exchange to glorify the general secretary: “Zelensky congratulated President Xi Jinping on his re-election, praised China’s extraordinary achievements and said he believed that under his leadership, China would successfully meet all challenges and continue to move forward.”

The CCP’s elaborate Russian dolls of rhetoric, painted with pretty phrases like “common prosperity” and “win-win cooperation,” may look to some in the outside world like real plans and strategies, an entire structure of responsible and well-thought-out proposals — even a “China solution” (to use another favored CCP buzzword). But they are always intimately connected to domestic power claims that have no business in practical and earnest deliberations over such important questions as peace in Ukraine.

Once we are done squeezing sense and significance out of Xi Jinping’s “Maospeak,” once we turn from the grandiosity of his nonsense, we are left with the same challenging set of questions that stand in the way of peace. We can count on Zelensky, the comedian turned statesman, to treat them with the seriousness and frankness they deserve: “No one wants peace more than the Ukrainian people. We are on our land and fighting for our future, exercising our inalienable right to self-defense,” the President said during his call with Xi, according to Ukraine’s more intelligible summary. “Peace must be just and sustainable, based on the principles of international law and respect for the UN Charter. There can be no peace at the expense of territorial compromises. The territorial integrity of Ukraine must be restored within the 1991 borders.”

Zelensky, his head beneath the clouds, also made a practical point that chastened China for its tacit support for Russia’s act of aggression. “Russia converts any support — even partial — into the continuation of its aggression, into its further rejection of peace,” he said. “The less support Russia receives, the sooner the war will end and serenity will return to international relations.”

With so much at stake for Ukrainians and the rest of the world, we should certainly welcome all genuine efforts beneficial to the peaceful resolution of the war in Ukraine — to follow, I suppose, the last of China’s “Four Shoulds.” But the Chinese Communist Party’s seeming incapacity to part with its obtuse rhetoric — so bloated with self-glorification, so turgid with over-promise, and so spectacularly arcane — is a serious impediment to international understanding that should itself be a cause for concern as China steps up its bid for global leadership.

Beyond distracting from rights-based values and encoding authoritarian ones in a bait-and-switch fashion, this rhetoric invites deadly miscalculation.

In an article for Foreign Affairs in late March, former Beijing Bureau Chief for The Washington Post John Pomfret and former Deputy National Security Adviser Matt Pottinger wrote on the basis of their expert reading of four recent Xi Jinping speeches that the leader is “preparing China for war” in the Taiwan Strait. The article was an alarm bell. But responding one month later, a group of students, interns and former state media reporters on a well-known Substack account operated from China argued that the conclusions in the Foreign Affairs piece were based on misreadings of China’s politics, its press system and its odd official discourse, and that they fueled “an unnecessary sense of panic.”

The lesson I took from this tremor of discussion was just how impenetrable China’s official discourse in speeches and in the press is — not only to those with a deep experience of the country and fluency in its language as they gaze from the outside, but also to those reading from inside the country. And it occurred to me just how perilous our lack of clarity about China has become, a problem compounded by the CCP’s monopoly on expression domestically, which has obliterated individual voices and their moderating influence, and has condemned ordinary citizens to ignorance about their own society.

During his first months in power, Xi Jinping crafted an image of himself as a down-to-earth man of the people. He pledged an end to formalistic pronouncements and encouraged a more informal style among his fellow officials. This proved to be an anti-bluster bluster. Since that time, Xi has compounded China’s political culture of grandiosity, placing himself atop a lofty pyramid of concepts created by a corps of Party discourse engineers below. Because the Party is so fixated on verbal monument-building, it has now even posited a distinctive “Chinese discourse system” for what thinkers like Zhang Weiwei (张维为), a key advisor, say will be a new era of “post-Western discourse.” It talks about a “strategic communication system with Chinese characteristics.”

The distinctiveness of CCP-speak is not a gift to human civilization. In fact, it is a growing international problem. An abyss of potential misunderstanding lies between the reprehensible rantings of diplomats like Chinese Ambassador to France Lu Shaye, who enraged many in Europe last month by outrageously questioning the sovereignty of former Soviet states, and the absurd “Maospeak” of mainstream CCP discourse, which can say nothing without magnifying itself.

Speak plainly, Mr. Chairman. What do you mean when you talk about “peace”?

(This piece was first published on China Media Project, reprinted with the author’s permission.)

Have you read?

- A model opera at Lujiang middle school

- Exhausted post pandemic China dreams of rural life

- What does Xi’s new army mean for China’s future?

Uploaded by Ian Huang