“Xiplomacy” in the Shadows

Source:shutterstock

Chinese diplomacy has suffered many setbacks out in the open and around the negotiating table in recent months. But it could be flourishing in the margins, where a complex array of offices and institutions are working to push party-state agendas in ways that often go unseen.

Views

“Xiplomacy” in the Shadows

By David L. BandurskiFrom CommonWealth Magazine (vol. 779 )

This has been a summer of failures and setbacks for Chinese diplomacy, and it is tempting to see the adverse effects of Xi Jinping’s ill-advised “wolf warrior” diplomacy coming home to roost at last.

In Europe, China seems to have lost its charm offensive. “De-risking” is now the overarching consensus in the G7 and the European Union. Anxious to find a detour around the self-created roadblocks to national-level diplomacy, China has prioritized “non-governmental diplomacy,” Xi Jinping telling Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates hopefully in June that “the foundation of China-US relations lies in the people.” Days later, Premier Li Qiang (李强) made similar appeals to German and French industry representatives, but pretty words about “enlarging the cake” have rung hollow as trade groups from both countries report “a more volatile operating environment.” Finally, the end of July brought Chinese diplomacy’s most spectacular own goal, as the country’s foreign minister, Qin Gang (秦刚), was hastily removed from his post. Qin continues to be “missing,” and the unexplained episode has deepened existing perceptions of China’s volatility.

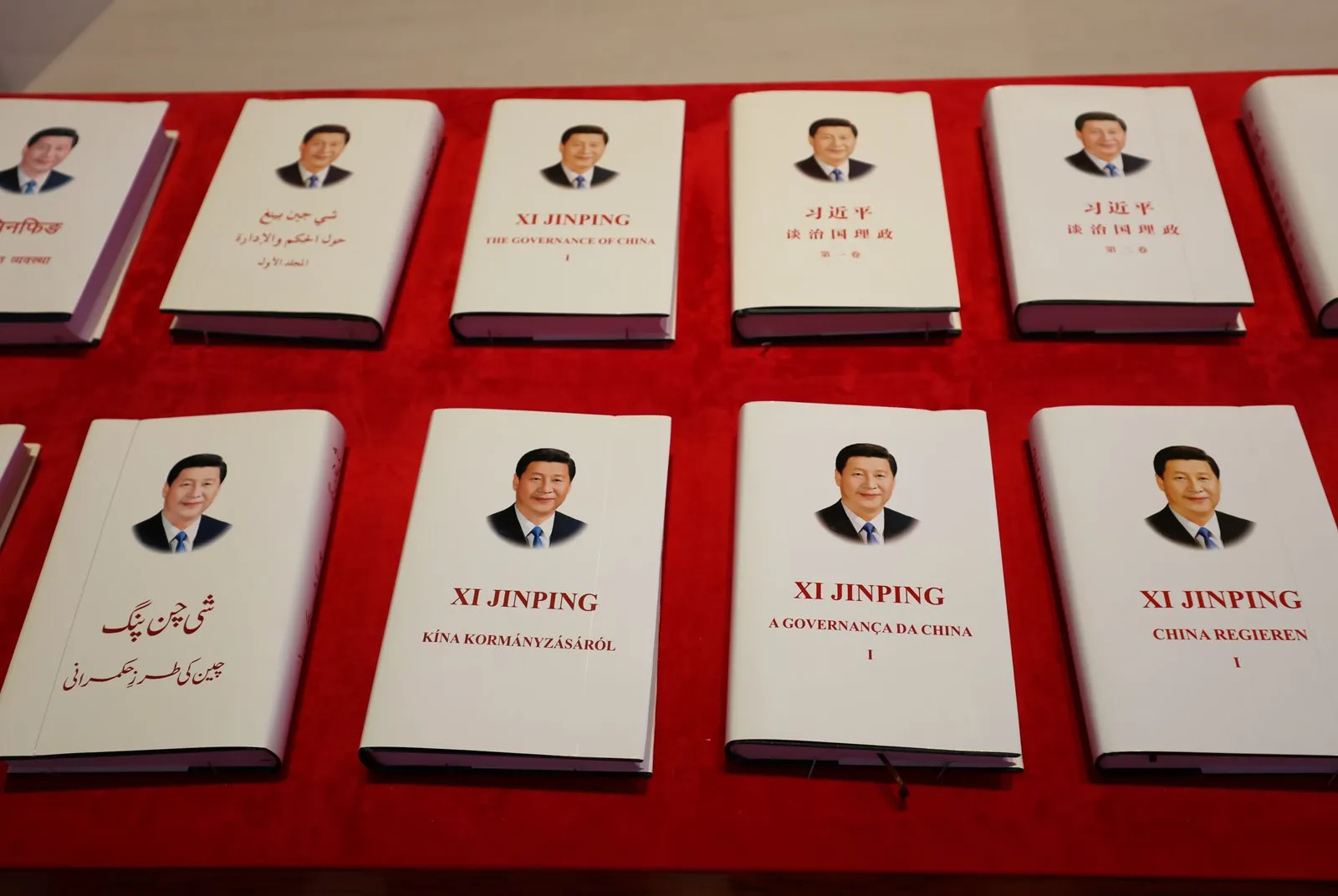

But while “Xiplomacy,” as party-state media have affectionately called it, has stumbled tremendously out in the open, it is striding confidently in the shadows. China is making huge investments in more indirect forms of diplomacy, notably in media diplomacy, that could pay off in the longer term — and that deserve greater scrutiny from the rest of the world.

Behind the Curtain of “People-to-People” Exchange

In fact, the vast majority of China’s efforts to influence countries and institutions globally look at first glance like what China likes to call “people-to-people” exchanges. As efforts by the party-state to influence local people and groups in our societies, these are generally cloaked and invisible — either because their party-state links have been actively hidden, or because we lack sufficient knowledge of China’s political mechanics to really see who is acting, and what is happening. For countries, societies, and institutions (for example, the United Nations) that are vulnerable to China’s “people-to-people” assertion of its values and agendas, it is crucial not just to watch the drama onstage, but to peek behind the curtain.

The Chinese Communist Party has long maintained control over society, and this is truer Xi Jinping’s so-called New Era than it has been at any point in the reform era. Since he came to power in 2012, Chinese civil society has been in rapid retreat. The very word “civil society,” in fact, is now unwelcome. Remember this when you hear Chinese officials, or partners, talk about “people-to-people” exchange.

Achieving influence over public opinion regionally and internationally, what Xi calls “telling China’s story well,” has become one of the country’s signature efforts. It increasingly involves an array of actors so perplexing anyone could be forgiven for not seeing the face behind the curtain. They include party-state media groups and affiliated “brands” (a common cloaking technique); professional organizations and regional networks that pretend independence but mirror state agendas; universities cashing in on state grants for “external communication”; online “influencers” who appear to be acting on their own but are conduits for state propaganda; and of course the foreign ministry and party-state organs.

Telling the Mekong Story

To understand how this works, we can look at the more recent case of media diplomacy in Southeast Asia, where China has been keen to convince local populations of the goodness and generosity of the Chinese government in pushing infrastructure projects, including dam projects, in the Mekong Basin. In particular, China has sought to counter the view, supported by a wide range of experts, that the country’s dam projects have been devastating for the region.

Scientific experts now argue that the disequilibrium in the Lower Mekong Basin is approaching an ecological tipping point, with much of the blame owing to Chinese dams. “Most communities don’t know about what is happening in other sections of the river,” Brian Eyler, the Southeast Asia program director of the Stimson Center and co-lead of its Mekong Dam Monitor Project, told The Diplomat last year. “The Mekong is dying a death of a thousand cuts from these dams.”

According to the state narrative, however, China is not just blameless but should be thanked for its technological generosity and scientific know-how. In a phrase often seen in external propaganda about the region, Chinese officials and state media like to say that they have “regulated floods and replenished droughts.” In a paper last year, Hoang Thi Ha, a senior fellow at Singapore’s ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, wrote that this phrase has been central to the “positive framing of its dams as providing regional public goods.” The phrase is routinely used to promote the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC) sub-regional mechanism launched by China in 2016, which Hoang and others say applies a state-centric approach — cutting out local communities and civil society groups in the basin, which have been more vocal on the impact of the dams in recent years.

So much for “people-to-people”

Last month, in the latest effort to drive the narrative of Lancang-Mekong development in ways favorable to China’s interests, the country hosted the Lancang-Mekong River Cooperation Media Summit, an all-expenses-paid tour for scores of journalists from Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam. The event was hosted by the People’s Daily, the flagship newspaper of the CCP Central Committee, and had the support of its Central Propaganda Department, which supplied the keynote speaker, Minister of Propaganda Li Shulei. In a report on the event called “Telling the Mekong Story,” a reference to Xi Jinping’s central catchphrase for external propaganda, “telling China’s story well,” the People’s Daily said that “media cooperation is an important force in promoting humanistic exchanges and enhancing friendship and mutual trust.”

Media cooperation was chiefly about furthering the state narrative. In a quote almost too good to believe, and using the familiar flood-and-drought phrase, Souksakhone Vaenkeo, the deputy editor of the Vientiane Times, told the People’s Daily: “China scientifically dispatches Lancang River’s graded hydropower plants to give full play to the role of ‘regulating floods and replenishing droughts’ in disaster prevention and mitigation.”

Another too-good-to-be-true quote came from Vietnamese journalist Nguyen Thi Yen, who reportedly said as she raised her mobile to take a snapshot of a Chinese wind power project: “I hope China will promote its wind power construction experience to drive sustainable development in Southeast Asia.”

New Media Networks for China’s Story

So-called media cooperation is about more than paid-for junkets to China, and it involves more than just central-level media and agencies. As part of the Lancang-Mekong River Cooperation Media Summit, the delegation also visited Yunnan province in China’s southwest, where the Mekong runs through a steep gorge and is trapped by 11 mainstream dams before it ever enters Laos. There they visited the offices of Yunnan Daily, the official mouthpiece of the provincial CCP committee, where they joined a pledge of cooperation.

Yunnan Daily also runs a new multimedia brand called the Mekong News Network, which consolidates the content of four publications and one website already produced by the newspaper group in Burmese, Thai, Khmer, and Laotian, as well as a multilingual website aimed at the region. The brand aims to provide news and information directly to media partners in the region, and will also serve as a platform for continued cooperation.

When China talks about media cooperation, what it is generally seeking is media distribution. News and videos from the Mekong News Network are present already on international social media platforms such as Facebook, distributed through proxy accounts of the provincial government without any mention of their origin. And as Mekong News Network stories are increasingly fed through local media in Southeast Asia, which is the ambition, they will be similarly cloaked. News consumers will be deprived of the basic information they deserve about the powerful interests lying behind the information.

The Mekong News Network is also part of a broader nationwide trend of empowering provincial and even city-level propaganda departments to turn their own resources to Xi Jinping’s grand project of “telling China’s story well.” The brand was set up in May 2022 under the “Yunnan Provincial International Communication Center for South Asia and Southeast Asian Regions,” an office under the Yunnan provincial propaganda department that officials last year called “a new journey for Yunnan’s international communication.”

Provincial officials have said publicly that the communication center and its multimedia brand are a direct response to Xi’s call in May 2021, during a collective study session of the CCP Politburo, to strengthen China’s “international communication power” and “communicate China’s voice.”

Gansu province launched its “international communication center” in August last year. Chongqing followed suit three months later, and now, under the direction of the municipal propaganda department, runs iChongqing and Bridging News, media brands on Western social media platforms that are deceptive about their origins. Bridging News tells its 250,000 combined followers on Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube that it is “dedicated to business headlines in China and the world at the forefront of the Belt and Road Initiative.” The outlet specializes in feel-good business and cultural promotion and a bit of panda bear public diplomacy, but veers into misinformation and outright propaganda. One recent post lauds China’s economic recovery, citing a healthy housing sector — despite the fact that all credible sources continue to report that the property sector is in crisis.

Several more international communication centers have been launched in just the last month — in Jiangsu province, Hunan province, and the city of Shenzhen. Much as Yunnan’s center is meant to direct its activities toward Southeast Asia, Shenzhen’s center is to focus on the Greater Bay Area, which includes Guangdong, Hong Kong, and Macau.

This growing network of international communication centers clues us into one broader development in the transformation of China’s external propaganda efforts. In the past, these efforts have unfolded largely from the central level, from state media such as Xinhua News Agency, China News Service, China Daily, and the China Media Group (with networks like CGTN), as well as through China’s overseas diplomatic missions. Increasingly today, they are also happening through provincial and other local actors, as Xi Jinping’s push to “strengthen international communication power” picks up pace.

One of the more unlikely players recently on external propaganda in Southeast Asia has been the northeastern province of Heilongjiang, the area of China most distant from the region. In May, Heilongjiang hosted Chinese-language journalists from Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar, and other ASEAN member states for an online conference and training session in Phnom Penh supported by the province’s Foreign Affairs Office (FAO). The main address was delivered not by a professional journalist or media entrepreneur, but by Heilongjiang’s top diplomat, Wu Wen’ge, who said the purpose was to “promote understanding of Heilongjiang among media in the ASEAN region.”

The point is not to respond to such efforts with fear, but rather the need to better understand them, and to equip our societies, and our media, with the tools they need to see them for what they are — attempts to suppress much-needed debate about China’s role and actions in the world. As free and open societies, it is crucial for us to understand both the complexity and the urgency, and to respond with determination and calm, bringing “Xiplomacy” out of the shadows.

Have you read?

- Besides Qin Gang, another Xi confidante has also been missing

- China's "Japanization": Is 30 years of decline to come?

- China's new red entrepreneurs

Uploaded by Ian Huang